People

Painter Sam Gilliam Spent His Entire Career in Washington, D.C. Here’s How the City Sustained Him When the Art World Wasn’t Watching

Here's what the late painter, who died last month at the age of 88, meant to the city.

Here's what the late painter, who died last month at the age of 88, meant to the city.

Kriston Capps

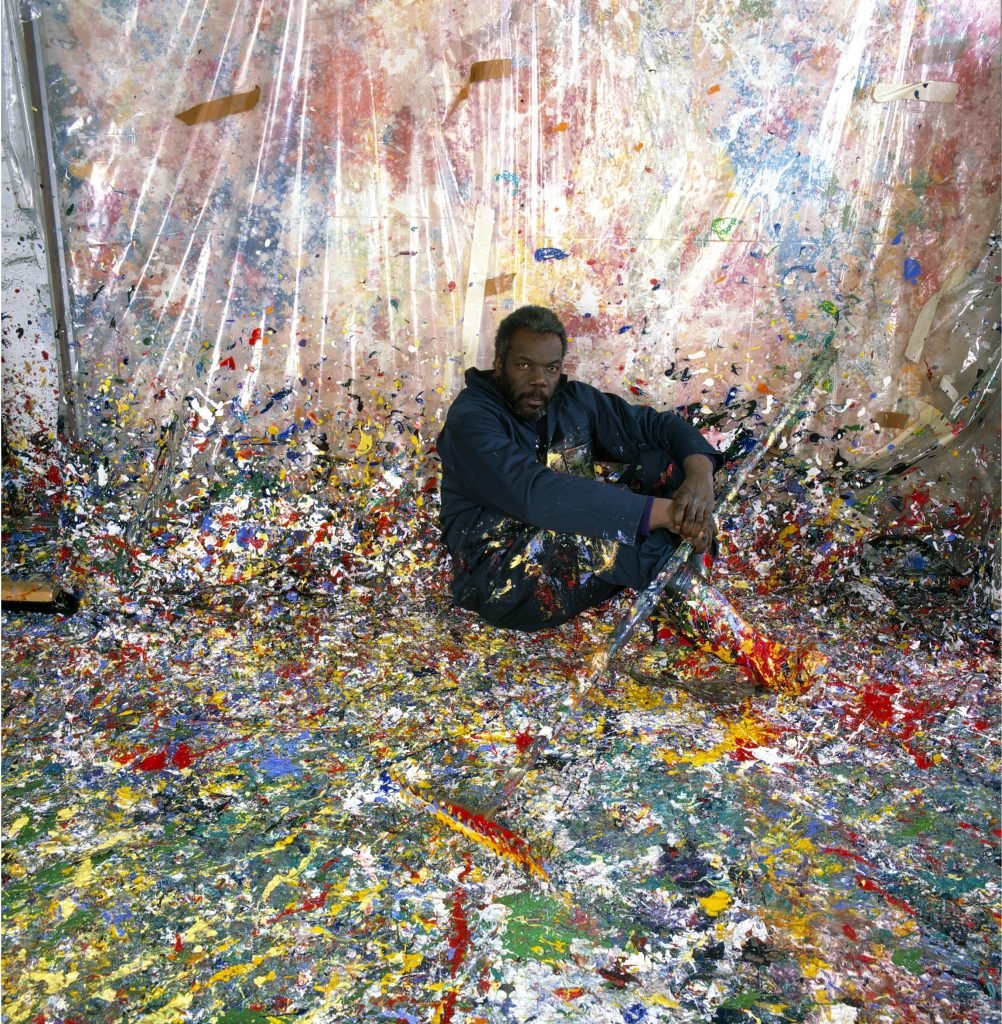

For an exhibition in 1998, the Kreeger Museum invited Sam Gilliam to take over. He could do whatever he wanted, as long as it related in some way to the modernist museum, a mansion-turned-jewel-box private collection in one of Washington, D.C.’s toniest neighborhoods.

He set to work building a birch plywood structure in the museum’s salon and attached a canvas to it. It was a variation on a theme he had been exploring for decades, breaking apart his paintings and putting them back together again.

Judy Greenberg, the museum’s director at the time, didn’t think the piece worked, and made her feelings known to the artist. Moments later, one of Gilliam’s assistants tracked her down in her office. You have to go and look at the pool, she was told.

Gilliam had taken the canvas off of the plywood structure “and threw it into the pool,” Greenberg recalled. “He was excited about it. I was excited about it.”

For several weeks, the canvas idled across the surface of the water, bunching and scrunching from one end of the pool to the other, supported by a custom floatation device Gilliam built to keep the gag going. An archival photo might be the only proof that it ever happened.

Sam Gilliam’s aquatic installation at the Kreeger Museum. Photo: Stephen Frietsh/Kreeger Museum

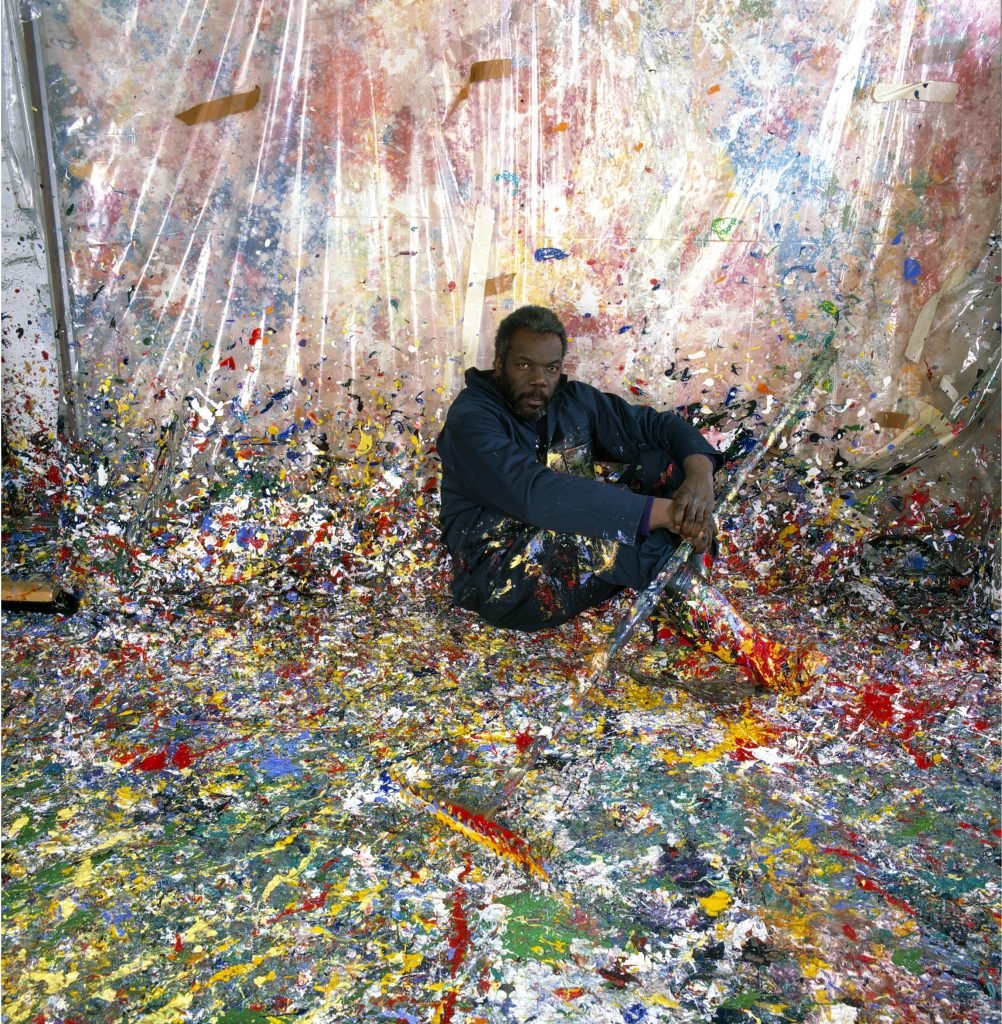

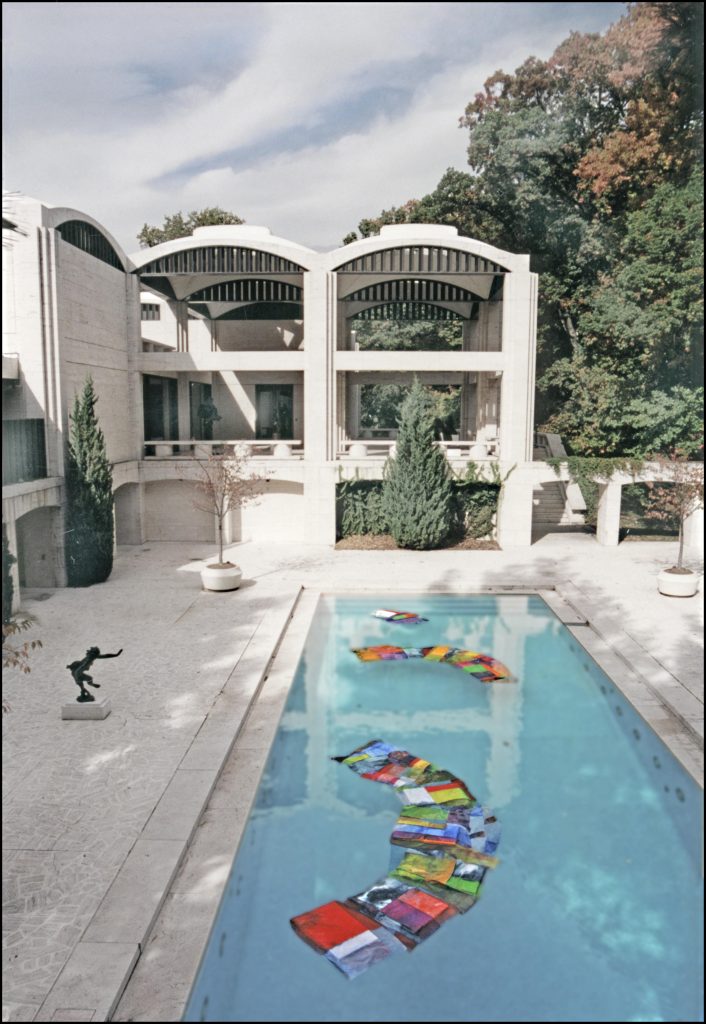

Gilliam, who died on June 25 at the age of 88, led a riot in color and shape over his career. He is best known for blowing the lid off of late modern abstraction by freeing his canvases from their supports. His elegant draped paintings earned the respect of the art world and, eventually, the attention of the market, making him the Washington Color School’s most famous alum, summa cum laude.

Yet the Gilliam that only Washington knows is the artist who worked tirelessly to perfect his formal experiments, even when the world wasn’t watching. His story is deeply connected to the District of Columbia, where he lived and worked from 1961 on. Gilliam helped keep many of its institutions afloat over the years, and vice versa.

“Sam was always the first name in art in Washington, no matter when a person would have asked the question,” said Jonathan Binstock, director of the Memorial Art Gallery at the University of Rochester, who in 2005 curated the last retrospective of Gilliam’s work, at the now-defunct Corcoran Gallery of Art. “Washington was his adopted home. Washington adopted him, too.”

The attention of the country’s top museums proved fickle early in his career. One of his paintings was acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art the year it was made, in 1979, only to be placed in storage for decades. Meanwhile, the market only began to give him his due 40 years after he represented the U.S. at the Venice Biennale—becoming the first Black artist to do so—in 1971.

A critic might have observed that by 1998, the party was over for Gilliam. The solo showcase at the Kreeger was one of his only museum appearances that decade. While he showed consistently throughout his career, especially in Paris, in the U.S. during this period his work appeared less frequently outside D.C. galleries such as Marsha Mateyka, Middendorf, and Baumgartner. Although hardly a vision of failure—many artists aspire to this level of success—it was a slide from landing the cover of Art in America in 1970.

US Secretary of State John Kerry congratulates US artist Sam Gilliam during an Art in Embassies Medal of Arts Award event at the US Department of State January 21, 2015 in Washington, D.C. (BRENDAN SMIALOWSKI/AFP/Getty Images)

The photo of Gilliam’s extemporaneous painting afloat in the water might point to the currents that can frame an artist’s career. These vicissitudes can be easy to overlook for a painter who ultimately achieved blue-chip status: A 1971 painting by Gilliam, Lady Day II, sold in 2018 at Christie’s for a record $2.2 million. According to Binstock, though, Gilliam was always going to do it his own way, no matter the circumstances.

“All artists have their ups and downs in terms of recognition. He set out in the very beginning to compete with the very best of the painters who preceded him and who were his contemporaries,” Binstock said. “And frankly even those who came after him.”

A 2014 profile in T Magazine of David Kordansky—the Los Angeles dealer credited with reviving Gilliam’s career—ran with an apocryphal story that Gilliam once traded artwork for laundry detergent. That wasn’t true (and the anecdote was retracted). But Gilliam did trade three paintings (plus $60,000) for the keys to a multi-story building in the heart of Washington, at 14th and U Streets NW, which would serve as his studio for more than two decades.

Sam Gilliam’s mural at Takoma Station, From a Model to a Rainbow (2010). Photo by Larry Levine/WMATA

Working on U Street through the 1980s and ‘90s, when the city itself was suffering disinvestment and decline, took commitment. The artist headed into his studio day in, day out, until 2010, when, at 77, he moved into a larger space at a converted warehouse in the city’s Sixteenth Street Heights neighborhood.

“Though Sam became a global art legend, he never moved to London or New York or Paris or Berlin,” wrote Chad Clark, the singer of the band Beauty Pill, in Washingtonian. Clark’s music studio was adjacent to Gilliam’s first studio. “He was a D.C. motherf*cker. I don’t know if he conceived of himself as ‘bringing honor to the city,’ but that is precisely what he did.”

During the years when his work was less popular, pieces by Gilliam became part of the Washington’s cultural fabric. One of his paintings graces National Airport. Downtown’s Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library is installing a Gilliam painting in September that belongs to the city. His work can be found at the Takoma Metro Station and the Walter E. Washington Convention Center. Every modern art museum in town displays his work.

Even after the market rediscovered Gilliam, museums did not quickly take up his later paintings. For example, a major survey by the Kunstmuseum Basel in 2018—his first solo exhibition in Europe—focused on drapes and other paintings he made between 1967 and 1973. But Gilliam never stopped making vital work—and D.C. institutions never stopped showing it.

Installation view of exciting, A Kite, Four for Annie G, and You Blue Moon (all 2021) as part of “Sam Gilliam: Full Circle” at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, 2022. Photo by Ron Blunt.

Gilliam’s most recent paintings, now on view at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, take the form of round, beveled-edge abstractions. He made these tondos in 2021 by smearing and layering acrylic with thickening agents, metal shavings, wooden fragments, and other scraps from his studio, then dragging the surface with a metal rake.

“No matter who was watching him or commenting on the work, Sam was in the studio, making the work,” said Evelyn Hankins, curator for “Full Circle.”

Perhaps his rising and falling and re-rising star in the art world owes to his status as a Black painter. Darby English, the author of 1971: A Year in the Life of Color, writes that for Black artists, “taking up a position within modernism also meant taking some distance from the Black community that articulated itself by insistently representational terms.” Gilliam, like his fellow Washingtonian Alma Thomas, insisted on a nuanced idea of Black abstraction that defied easy categorization.

As the art world embraced a more complex understanding of how Black artists related to abstraction, Gilliam and Thomas enjoyed a revival. That was true even in D.C.: The Phillips Collection, which hosted a retrospective for Thomas, put one of Gilliam’s paintings at the center of the museum’s 100th anniversary celebration last year. That painting, April (1971), makes reference to Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination and the riots that followed in D.C.

Sam Gilliam, Lucky (detail) (2021). Courtesy of the artist. © 2022 Sam Gilliam/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Ron Blunt.

Some institutions never gave up on Gilliam, such as the Speed Art Museum in Louisville, Kentucky (his birthplace) and the Studio Museum in Harlem. Washington, the city he called home, also stuck by him. Binstock said that when he was hired as a curator at the Corcoran, it was on the condition that he would start working on a retrospective for Gilliam. When the Kreeger put on Gilliam’s work in ‘98, he was the first artist to show solo at the museum.

Gilliam’s aquatic installation at the Kreeger was one more experiment in his relentless steam of ideas. Never titled, the study was eventually fished out of the pool and returned to the studio.

“He fed the studio,” Binstock said, “and the studio fed him.”