Books

A New Book by Philip Guston’s Daughter Explores the Origins of the Painter’s Ku Klux Klan Imagery—Read an Excerpt Here

Guston painted the works to try to understand "What would it be like to be evil?"

Guston painted the works to try to understand "What would it be like to be evil?"

Musa Mayer

When Philip Guston was young, social injustice and the cruelty of the world reverberated deeply through his paintings. In 1968, the United States was again in a state of profound unrest, with its moral leaders assassinated, its inner cities rife with looting and rioting, and its police violently suppressing protestors; halfway around the globe in Vietnam, the death toll was steadily mounting. The art world had seemingly detached itself from the real world and was busily gazing inward, celebrating formalist abstraction and elevating consumerism.

Guston later spoke of what this time was like for him: “When the 1960s came along, I was feeling split, schizophrenic. The war, what was happening in America, the brutality of the world. What kind of man am I, sitting at home, reading magazines, going into frustrated fury about everything… and then going into my studio to adjust a red to a blue?

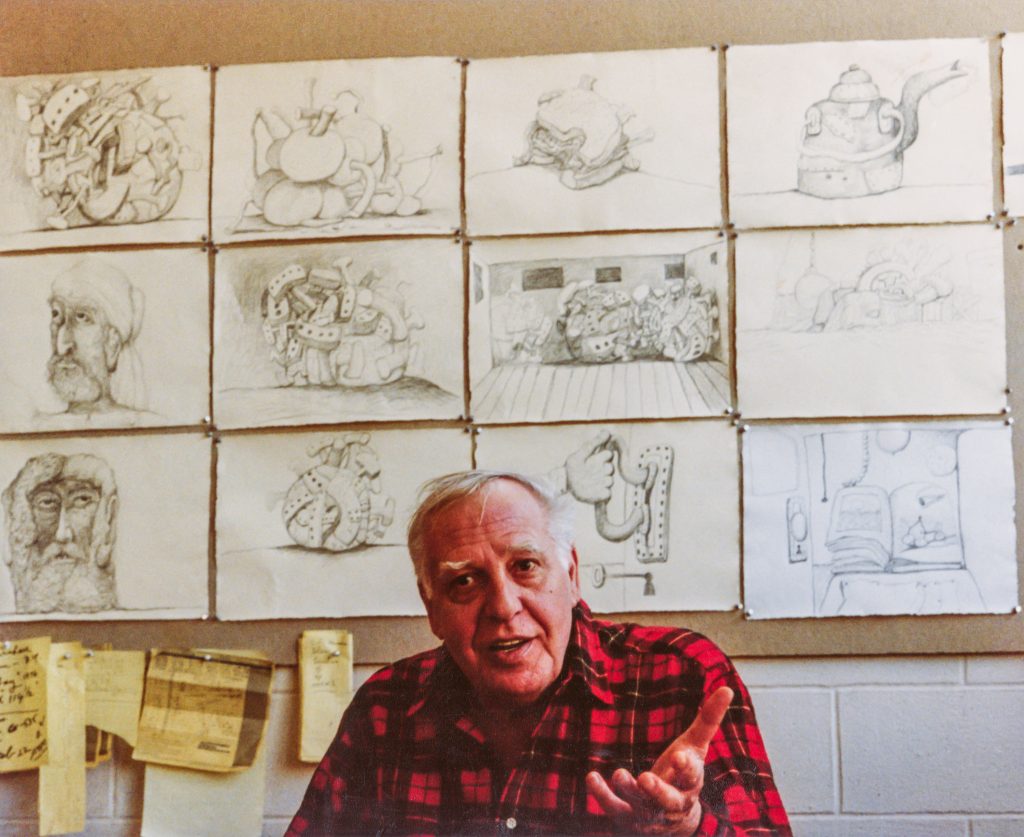

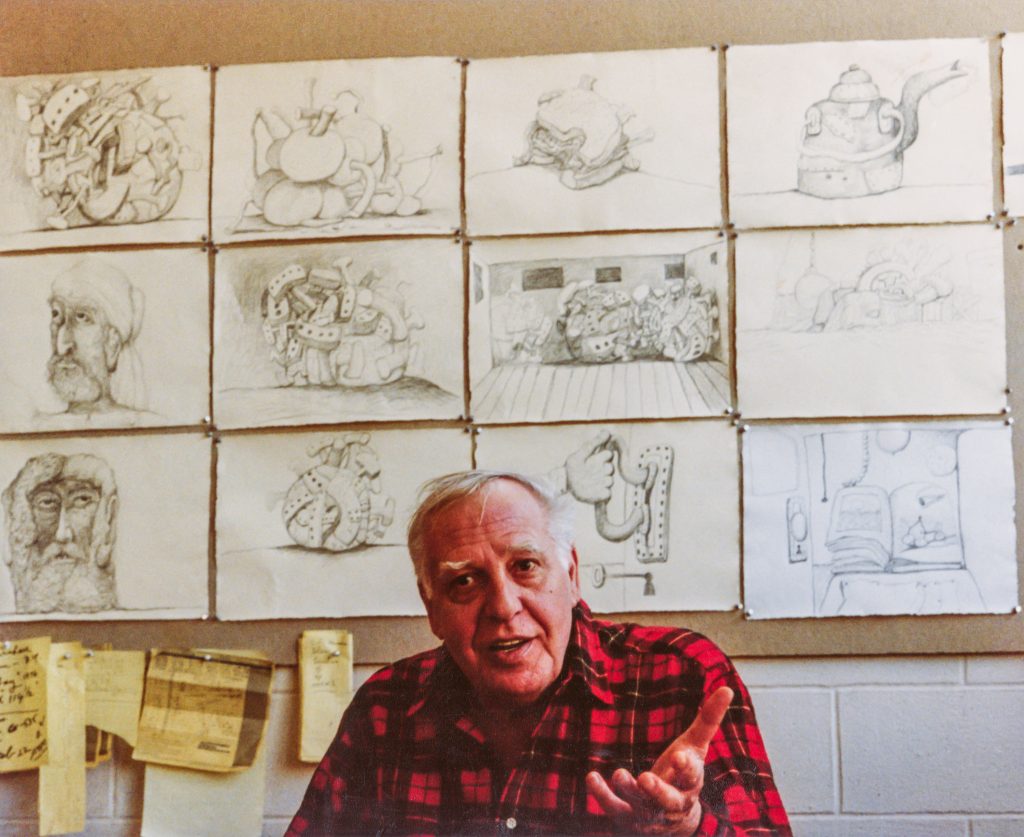

“I thought there must be some way I could do something about it. I knew ahead of me a road was laying. A very crude, inchoate road. I wanted to be complete again, as I was when I was a kid… wanted to be whole between what I thought and what I felt.” The acute self-awareness and sense of otherness that marked Guston’s reinvention are manifest in the explicit self-portrait Untitled (1968), in the enigmatic Head (Stranger) (1968), and even in the animal-like Paw (1968), foreshadowing the “crude, inchoate road” he felt destined to follow.

The potent images of Ku Klux Klansmen, masked and unpunished, had lingered in Guston’s psyche since boyhood. Representing America’s racist past—and present, as the tragedies of the civil rights movement unfolded—these new hooded figures became more than embodiments of evil and terror. With their capacity for cruelty now mixed with humor and vulnerability, even innocence, they were more complex and nuanced than that.

“They are self-portraits,” as Guston later explained. “I perceive myself as being behind the hood. In the new series of ‘hoods’ my attempt was really not to illustrate, to do pictures of the Ku Klux Klan, as I had done earlier. The idea of evil fascinated me… I almost tried to imagine that I was living with the Klan. What would it be like to be evil? To plan, to plot.”

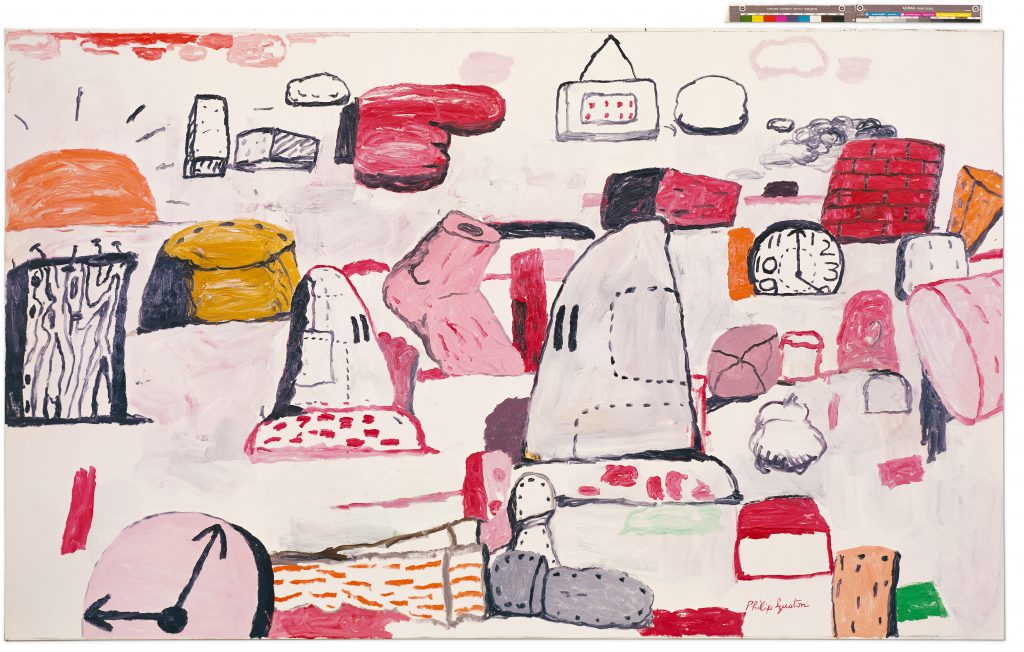

Philip Guston, Flatlands (1970). San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, gift of Byron R. Meyer. ©The estate of Philip Guston.

The “hoods,” as Guston called his cartoonish villains, range from crude outlines to fully developed tragi-comic characters. In Untitled (1968), a barely sketched hood raises a hand with a whip. Three hoods lined up in a row appear in Untitled (1968). More menacing, with haunted eyes, is the blood-spattered Untitled (1968). The bloodied Boot (1968) is deeply unsettling, as is Untitled (1969), an image of a hand with a finger drawing in blood. Within the empty studio of Untitled (1969), a canvas on an easel depicts a rain of fire or blood.

Although we see the hoods plotting, planning, and riding around, as in Untitled (Hoods in Car) (1968), we never actually see them executing their bloody deeds. At other times, as in Untitled (1968), they are like flagellant monks, self-castigating and bewildered.

In drawings, such as Untitled (1968) and the finely detailed Window (1970), as well as in large paintings, such as City Limits (1969), enigmatic scenarios unfold. The hoods inhabit the deserted landscape of City (1969), while in Flatlands (1970) they find themselves on a street littered with symbolic objects, overseen by a baleful sun. Sometimes they inhabit interior spaces, as in By the Window (1969) and Bad Habits (1970).

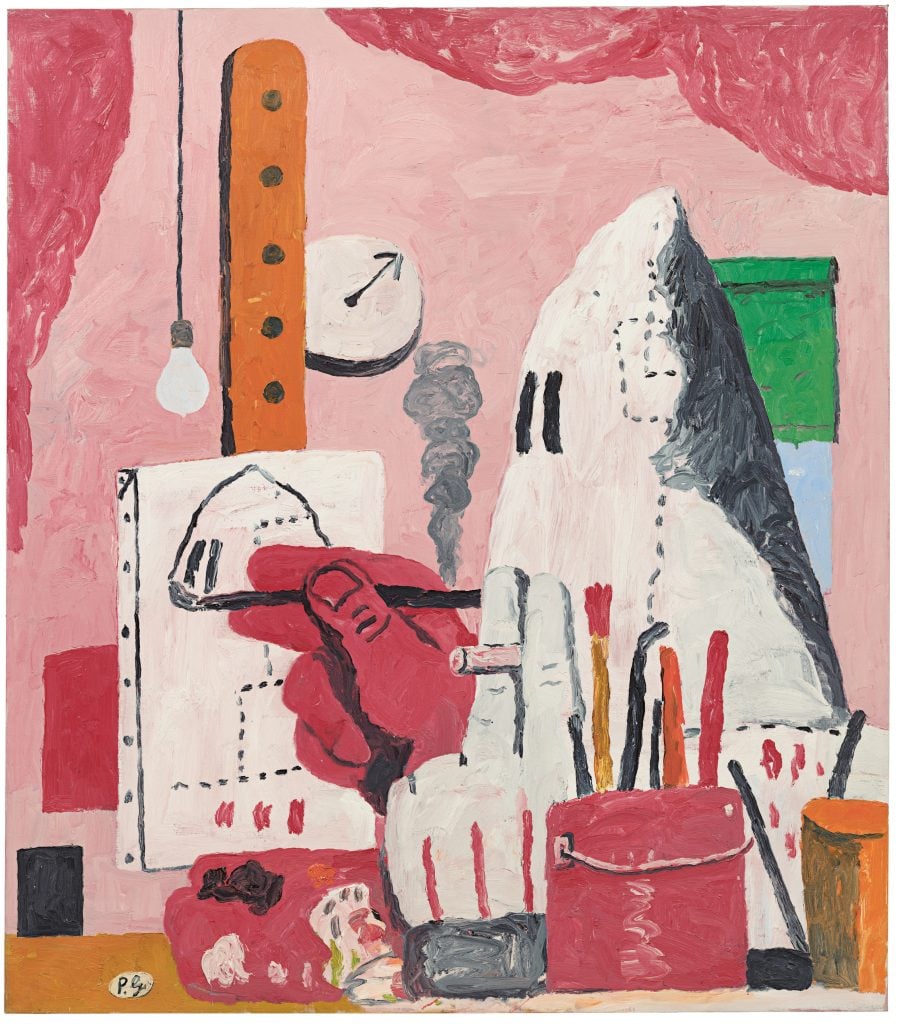

The seminal work of this series is arguably The Studio (1969), a hooded figure of an artist painting a self-portrait.

Philip Guston, The Studio (1969). Private Collection. ©The estate of Philip Guston.

In October 1970, when Guston first exhibited 34 of his new figurative paintings at New York’s Marlborough Gallery, the art world was shocked, and the critical response was resoundingly negative. “Clumsy.” “Embarrassing.” “Simple-minded.” “An exercise in radical chic.” The New York Times headline referred to the artist as “A mandarin pretending to be a stumble-bum.”

Willem de Kooning was among the few who understood. At the opening, he congratulated Guston, saying, “Do you know what the real subject is, Philip? Freedom!” Telling the story later, Guston added, “That’s the only possession the artist has—freedom to do whatever you can imagine.”

To avoid the controversy and negative reviews, Guston and his wife fled New York immediately after the Marlborough opening, boarding a ship bound for Italy, where he took up residency at the American Academy in Rome for the next seven months. There he felt himself drawn back to his pantheon of Italian painters of the past, the art that had first moved him to paint as a young man, and with Musa, he visited Venice, Padua, Arezzo, Siena, Florence, and Sicily.

At the start of 1971, he set to work in his studio at the academy. What emerged were the “Roma” paintings, a series of timeless small oils on paper inspired by Roman ruins and landscapes, clearly informed by Guston’s reimmersion in art and antiquity. Yet even in the Eternal City, haunting images persist.

In May of 1971, Guston returned to his studio in Woodstock. It was Richard Nixon’s first term as president, and the scandal of the Pentagon Papers was unfolding daily in the pages of the New York Times and the Washington Post, documenting decades of government deception concerning the war in Vietnam. The writer Philip Roth, a close friend of Guston’s, had turned to satire as a response with Our Gang, a send-up of Nixon’s administration. The potency of satire and its long tradition in art from Goya to Hogarth to Picasso, appealed to Guston as well.

Within a couple of months, over 200 wildly satirical drawings had flowed from his pen, and Guston selected 73 as a sort of narrative of Nixon’s life from boyhood to his ascent to the presidency. In these drawings, which Guston called Poor Richard, he first explored much of the imagery that would take form over the next decade in his paintings.