Art World

NYC’s Viral Portal Has Moved—Here Are 5 (Better) Artworks That Offer Views of the Other Side

Enter the looking glass.

The creators behind the famous NYC Portal have relocated their viral “technology sculpture” to Philadelphia. The Portal connects visitors via a live camera feed to its counterparts in a global network of similar sculptures in Vilnius (Lithuania), Lublin (Poland), and Dublin (Ireland).

Now situated in John F. Kennedy Plaza—better known as Love Park—the Portal faces stiff competition from one of the city’s most iconic landmarks: Robert Indiana’s renowned LOVE sculpture (1970), which has long been a fixture overlooking the square.

The installation, created by artist Benediktas Gylys, formerly established a live video link between New York’s Flatiron Plaza and Dublin’s O’Connell Street in a bid to encourage “global interconnectedness.” But since the circular sculpture was unveiled early in May, what it spurred instead was extreme and inappropriate behavior on the part of the public, who opted to flash middle fingers and, well, other body parts to onlookers across the pond. On May 14, the livestream ceased, before resuming five days later with limited hours and increased security to deter mischief-makers. The sculpture was originally slated to be relocated to an alternative site in New York after a temporary permit expired with Flatiron, the founder told NBC New York in August.

“The Portal’s arrival in the heart of Philadelphia is an exciting moment for our city that offers a new way to engage with the world, particularly ahead of America’s 250th anniversary in 2026. This project is a celebration of our city’s spirit of innovation and unity,” said Philadelphia city director Michael Newmuis.

The idea of a channel to the other side is not an isolated one, though—it runs through art history. For ages, artists (and not just Surrealists, mind you) have rendered doors, windows, eyes, and abstract forms to represent gateways to whole different dimensions. These separate planes might be underworlds as much as dream worlds, or simply, as Georgia O’Keeffe once put it, the “faraway.”

Here are just five of such eye- and world-opening works.

René Magritte

The False Mirror (1929)

René Magritte, The False Mirror (1929) on view at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Photo: Radoslav Cajkovic / Alamy Stock Photo.

Can you believe your eyes? Not if you ask Magritte, who once declared that “everything we see hides another thing”—a stance befitting an artist whose surreal juxtapositions stretched our understanding of reality. His 1929 canvas depicts a singular eye, its iris replaced by a serene, cloud-filled sky. The blue expanse, though, seems not reflected in the eye, but a view as seen through the window of the eye. It’s a visual illustration of a portal as much as the Belgian artist’s play on what it means to see. Man Ray, who once owned the painting, reported the work “sees as much as it itself is seen.”

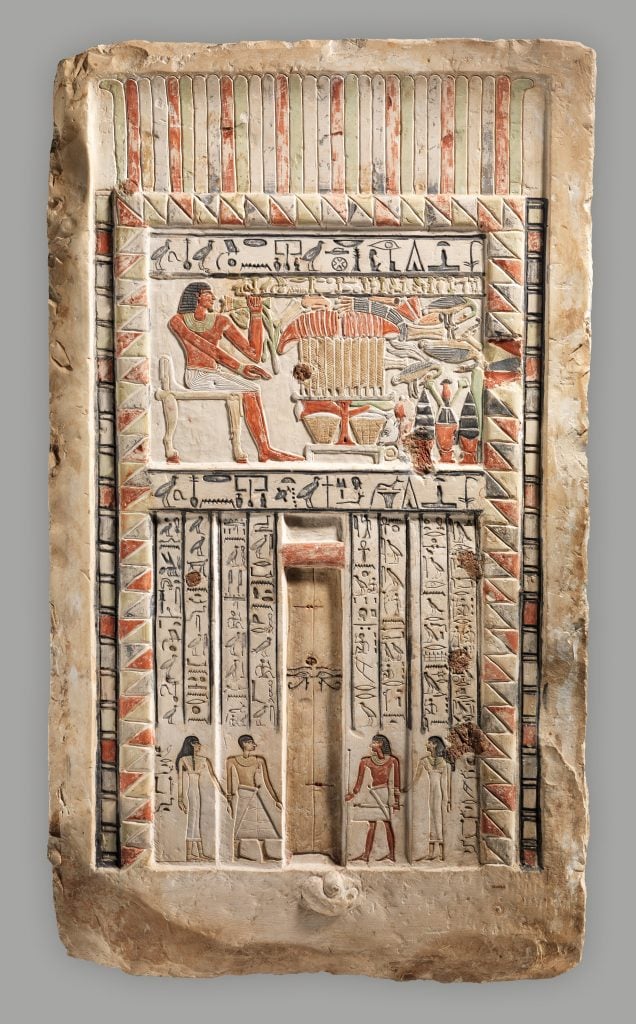

False Door of the Royal Sealer Neferiu (ca. 2150–2010 B.C.E.)

Funerary Stela of the Royal Sealer Neferiu (ca. 2150–2010 B.C.E.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1912.

This limestone stela is just one of hundreds of false doors or niches that archaeologists have turned up in Egyptian tombs. Among the cult of the dead in ancient Egypt was a belief that such false doors served as a portal between the living and the dead. The life force (or ka) of the deceased, it was thought, would pass through these monuments, at which visitors could leave offerings. These artifacts were often carved with scenes commemorating the owner; this one, held at the Met, depicts Neferiu seated at a bountiful table, alongside inscriptions celebrating his good deeds.

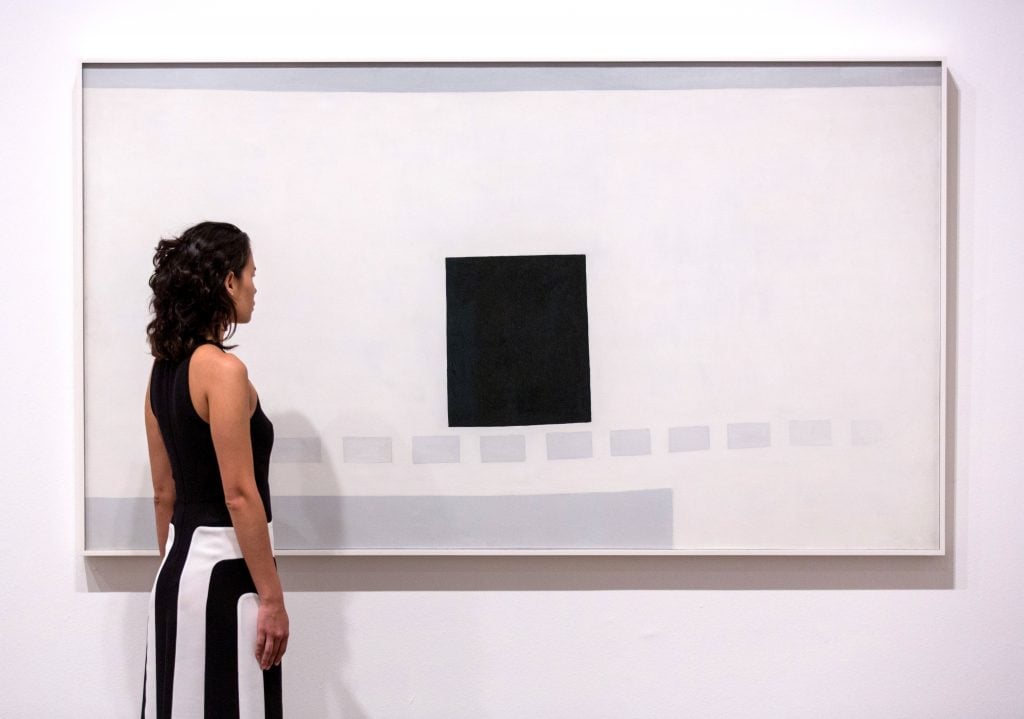

Georgia O’Keeffe

My Last Door (1952–54)

Georgia O’Keeffe, My Last Door (1952–54) on view at Tate Modern, 2016. Photo: Rob Stothard/Getty Images.

O’Keeffe infamously painted some 20 versions of the door to her Abiquiu, New Mexico home. “It’s a curse,” she once said, “the way I feel I must continually go on with that door.” Her various iterations never departed from simple geometric compositions—the door often reduced to a simple square or rectangle—differing only in the painter’s choice of colors. In doing so, she seemed less intent on depicting the actual entryway than capturing her emotions about it—which remained, it appeared, always just out of reach, as if behind a closed door. Despite its title, My Last Door was far from her last attempt to reach that opening.

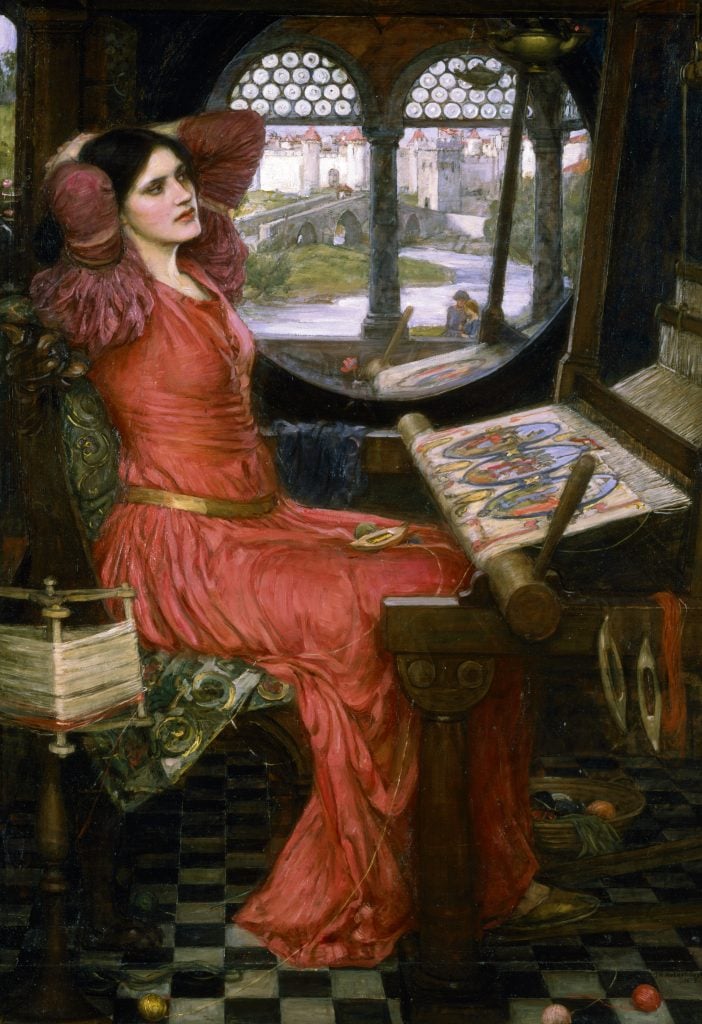

John William Waterhouse

I Am Half-Sick of Shadows, Said the Lady of Shalott (1915)

John William Waterhouse, I Am Half-Sick of Shadows, Said the Lady of Shalott (1915). Photo: Ann Ronan Pictures/Print Collector/Getty Images.

Waterhouse’s radiant work takes a leaf from Tennyson’s famed 1832 ballad, The Lady of Shalott, in which the eponymous heroine, burdened by a curse, is made to sit at a loom in a tower, weaving images of a world she is not allowed to glimpse. Barred from looking directly out a window, the Lady must instead view the world as reflected in a mirror—hence the “shadows.” The pre-Raphaelite painter catches her growing frustrated with her meagre portal, the luminous vista outside contrasting with her dim surroundings. Alas, the Lady is eventually tempted to look out the window and wander outside, thus bringing the curse upon her—scenes Waterhouse also painted.

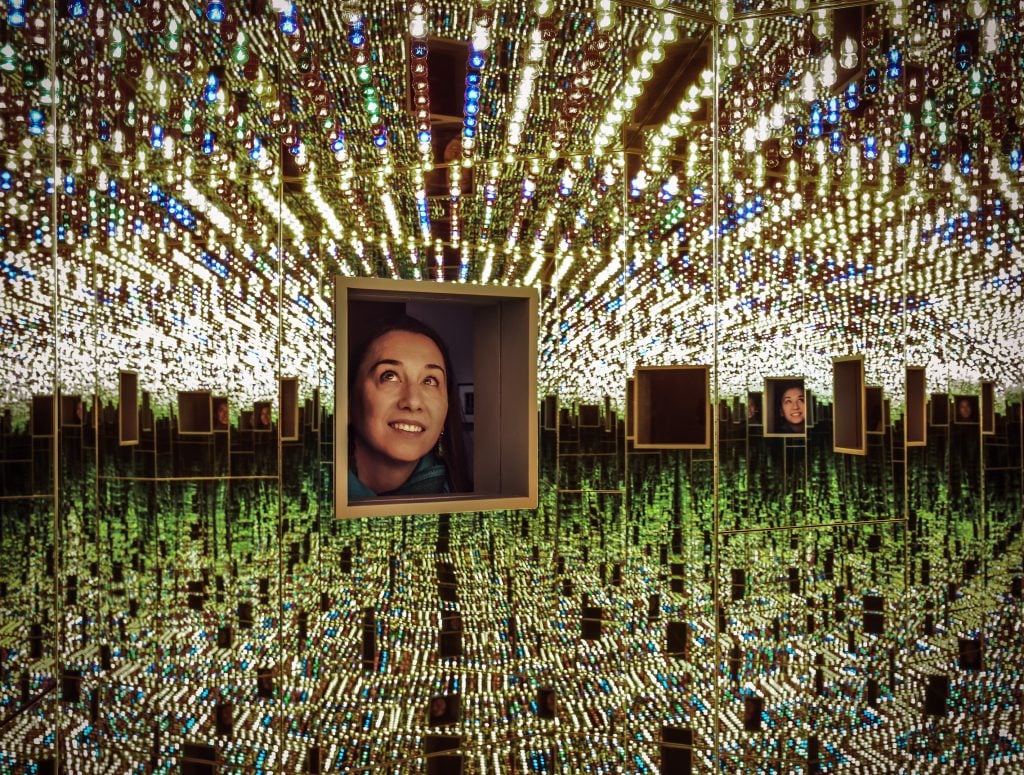

Yayoi Kusama

Infinity Mirrored Room – Love Forever (1966/94)

Yayoi Kusama, Infinity Mirrored Room-Love Forever (1966/94) on view at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C., 2017. Photo: Bill O’Leary/The Washington Post via Getty Images.

The self-described “modern Alice in Wonderland,” Kusama has made her name on her transportive Infinity Rooms, featuring mirrors and various sculpted forms. Unlike installations that visitors could enter, Love Forever, which began life as a 1966 work known as Kusama’s Peep Show or Endless Love Show, invited audiences to look through eye-level holes cut into the walls. What they would find through those portals are mirrored surfaces and colored lights, and the sight of their reflections multiplied across a boundless expanse—at one, as Kusama once said, “with eternity.”

This article was updated on October 23, 2024, to reflect the news about the NYC Portal’s relocation.