Moyra Davey has had a big year in Germany. The Canadian artist, based in New York for some decades now, showed an expansive group of over 100 new photographs at documenta 14 in Kassel, 70 C-prints and a new film in the quinquennial’s Athens chapter, and opened two solo exhibitions at both Buchholz Gallery’s locations, in Berlin (during Berlin Art Week) and Cologne, before closing out the year with the largest display yet of her Copperheads series at Frankfurt’s Portikus. But that’s not quite all. The exhibition in Frankfurt, titled “Hell Notes,” will travel to another institution, the Bielefelder Kunstverein, this February. So what’s behind Germany’s recent discovery of the artist’s work?

The appeal of Davey’s quiet language is indeed hard to resist. It is, after all, tactile and slow—something we can all agree is missing from our hyper-connected lives. With gestures like documenting her son’s name written in careful cursive, she is devoutly personal and human-centered.

For several decades, Davey has been considerately layering film, photography, and writing, her eye and voice lingering on daily minutiae, or places and things on the verge of obsolescence. Dust, empty cups, newsstand kiosks, pennies, or people writing while riding the subway are just some of the subjects carefully examined through Davey’s lens. Literary but never inaccessible, Davey came to prominence in the late ’80s after moving to New York to attend the prestigious Whitney Museum of American Art Independent Study Program. Soon after, the artist became a regular exhibitor throughout the ’90s at cult figure Colin de Land’s much-adored American Fine Arts Co., just south of SoHo.

Then, in 2009 for a group exhibition at the now-shuttered Murray Guy, Davey tried something: she folded up her photographs with tape, addressed, stamped, and posted them to the gallery, where they were opened, unfolded, and hung (she was in Paris at the time). The pairing of her intimate images with the anonymous traces of handling was well-received. Not long after, she opened her first European institutional solo show at Kunsthalle Basel, in 2010, then at Tate Liverpool in 2013, Vienna’s MUMOK in 2014, and more recently, at Bergen Kunsthall in 2016.

Moyra Davey’s Portrait/Landscape (2017), 70 C-prints, installation view, EMST—National Museum of Contemporary Art, Athens, documenta 14, photo: Mathias Völzke

Her works for documenta 14, Portrait/Landscape (2017) and Skeletal Buddha (2017)—shown in Athens and Kassel, respectively—followed her iconic postage-laden form; colorful taped bits and actual addressees (curators, gallerists, or assistants working with her on the exhibition) overlaid her ethereal black-and-white images. And it seems that this showing at documenta cemented Germany’s focus on the artist: After the Athens leg closed in July, Galerie Buchholz opted to rehang the works in Berlin alongside some older pieces in what felt like a miniature retrospective. Meanwhile, recently exited Portikus curator Fabian Schönheich also credits seeing her work at documenta for planting the seed for the Frankfurt show, which marks the artist’s first institutional solo in the country.

Film still from Moyra Davey’s Hell Notes (1990/2017).

For the show at Portikus and (soon-to-come) at Bielefelder Kunstverein, which focus on her Copperheads series, Davey also unearthed and restored a 26-minute Super 8 film, Hell Notes, first shown in the early ’90s at The Collective for Living Cinema (then an outpost for avant-garde film in Lower Manhattan that screened the likes of Yvonne Rainer and Carolee Schneemann). “It’s fun and gratifying to revisit something that may have had a short life or no life at all and to realize that its moment has come,” Davey tells artnet News. “I’d always thought of Hell Notes as key to reading the Copperheads, but never had the opportunity to show those works together.”

The work is essentially a moving picture collage. We see Davey in her apartment, which is also has her studio, as she films herself frying pennies in a skillet over a gas stove. The voices of her sisters are playing over an old answering machine. Cultural inquiry, literature, and family life—in Davey’s work, there are no boundaries or hierarchies between them.

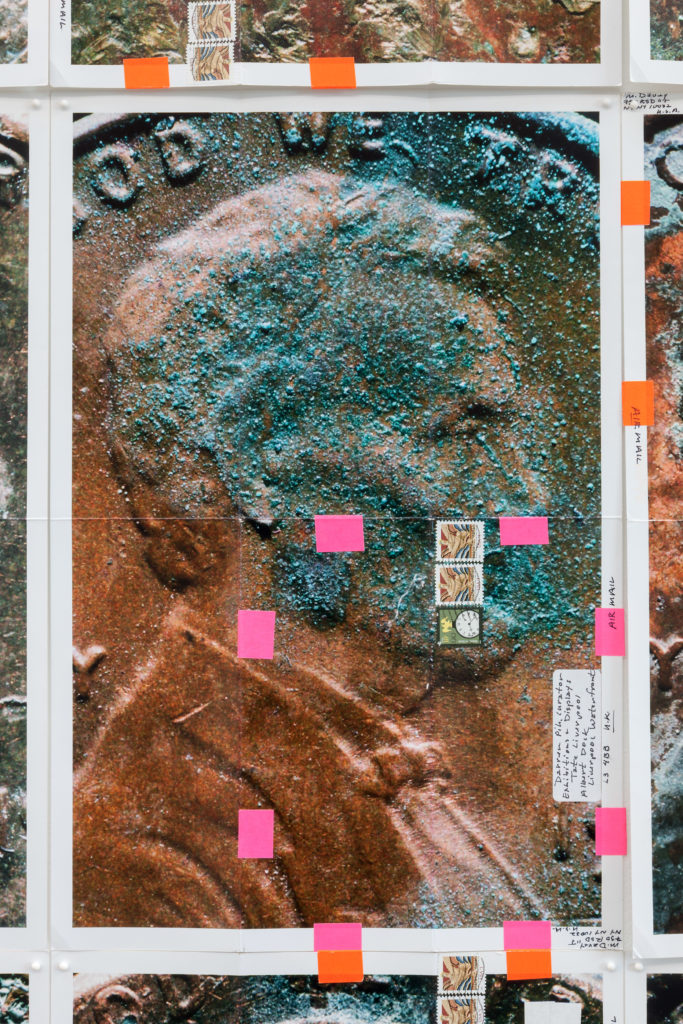

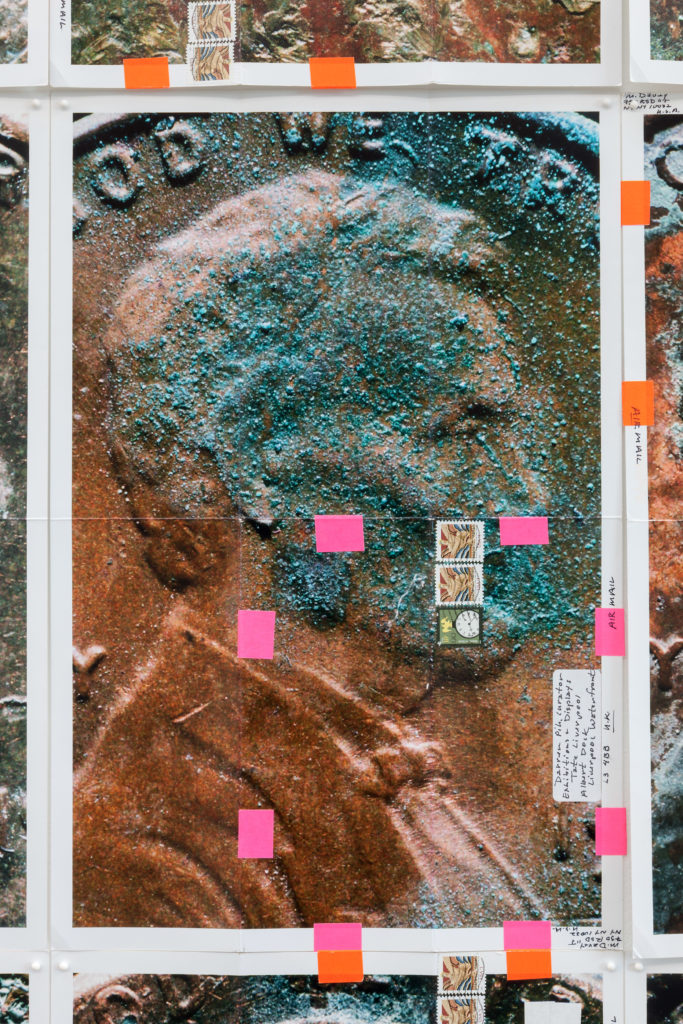

Moyra Davey’s EM Copperheads No. 1–150, Galerie Buchholz (1990–2017) and Copperheads No. 201–300, Eclipse, Portikus (1990–2017).

The serial works in Copperheads show grids of unfolded prints of old Lincoln-head pennies with their respective surfaces so scratched or oxidized that the old presidential profile has, in some cases, worn off completely. Fragments of postal addresses and names of addressees from previous shows are visible, like stamps analyzed for provenance. And while the debate in the United States whether to pull the one-cent coin from circulation remains unresolved, Copperheads teeters somewhere between the trivial and a relic.

“When I began collecting pennies for the Copperhead series, I’d just moved to NY, had no money and was thinking a lot about the psychology of money: Freudian ideas that equate money with excrement; the Potlatch custom of shaming a rival with extravagant gifts; profiles of 19th-century misers; and one famous counterfeiter,” Davey wrote in 2010. More recently, she has added to the ever-growing collection with something unexpected: a collection of pennies from Robert Mapplethorpe’s brother Edward, who lived in Davey’s building up until recently. Some 150 of them are on view in Portikus.

“For years he’d been telling me about his collection of old pennies,” says Davey of Mapplethorpe’s collection. “I was astounded by what he had. Here was someone collecting exactly the same gouged, dirt-encrusted, oxidized pennies I’d been slowly amassing for decades, but for what reason I still don’t know. I left his apartment with a bag full of coins and selected 150 of them to photograph.”

Portikus, a vertically stretched barn nestled on a miniature island about equal its size on the river Main, is a fitting backdrop for this work’s resurgence and rediscovery: The building’s large windows overlook Frankfurt’s financial district, the economic heartland of Germany (and in the wake of Brexit, of Europe.) Across the river, the city’s 46-foot sculpture of a glowing Euro symbol stands some blocks away from its seedy, drug infested red-light district.

View of Portikus, Frankfurt am Main

In one scene in the film, we see Davey seated on a Central Park bench musing to her friend while he eats a burger: “We value our money because we value our shit.” Her friend is filmed shaking money out of an old piggy bank from the hole in its rear. We hear Davey’s voice turning over the notion of Martin Luther writing up the 95 theses that started the Reformation while sitting on the toilet (as some historians believe). It’s a quiet film, but powerfully funny and severe.

“I had just completed an MFA and then the Whitney program in 1989 and suddenly everyone was talking about the market crash and oh, what an unfortunate time to be an artist,” Davey told artnet News. “I just kept working. My interests had less to do with global finance and more to do with the perverse psychological paradoxes of individual relations to money.”

Film still from Moyra Davey’s Hell Notes (1990/2017).

Since Davey first made this work, focusing on Manhattan and considering its underground vaults of gold and its dirty pennies, the U.S. has changed dramatically. Wealth has reached new heights, the relations between wealth and social injustice have been embodied by a new president, and bitcoin and cryptocurrencies were born, casting further doubts about global markets.

“Perhaps, if anything,” Davey tells artnet News, “my 1990 vision of excremental capitalism on the island of Manhattan is quaint compared to the monstrous, global version that now subsumes us.”