People

The Surreal Legacy of Adman-Turned-Fine-Artist René Magritte

Magritte also worked as an art forger.

Photo: courtesy Thurston Royce Gallery of Fine Art, LTD.

Magritte also worked as an art forger.

Amah-Rose Abrams

Surrealist painter René Magritte created some of the most instantly recognizable images of the 20th century. Using appropriated motifs and weaving them into his paintings, Magritte created timeless surrealist works that—despite the many times they themselves have been appropriated—still look fresh today.

Born in Belgium in 1898, Magritte’s early life was marked by tragedy as his mother sadly took her own life when he was only 13 years old. It is rumored that she was found, drowned, with her dress covering her face—an image that would reoccur throughout his work.

As a young man, Magritte studied at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels from 1916 to 1918, but ultimately found traditional study uninspiring. When he left art school, he worked as a draughtsman in advertising and in a wallpaper factory. It was during this time that he developed his keen knowledge about the power of clear messaging through imagery.

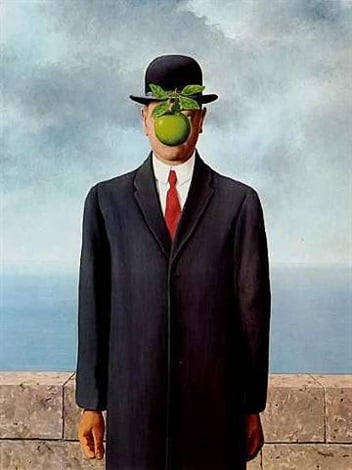

René Magritte Le Passager du Transatlantique (1936)

Photo: Gallery Automne

He began painting full time when he signed a contract with the gallery Le Centaure in 1926, and it wasn’t until a year later that he exhibited his early Surrealist work in his first exhibition, in Brussels. The show was excoriated by critics, and the disheartened young artist moved to Paris, where he met other Surrealists and his career really began to blossom.

Surrealism was following in the footsteps of the Dada movement, and Paris was at the center of all things avant-garde. On moving to the French capital, Magritte quickly met André Breton and other members of the experimentally playful movement.

Magritte returned to Brussels in 1930, and resumed working in advertising. He continued to paint, and spent time working at the house of Surrealist patron Edward James in London. James is featured in two of Magritte’s works, Le Principe du Plaisir (1937) and La Reproduction Interdite (1937).

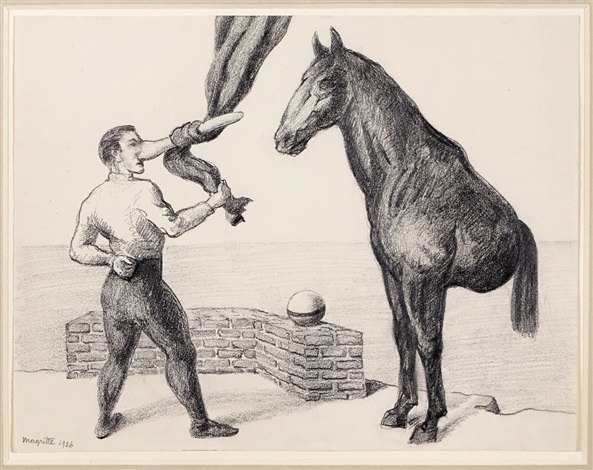

Réne Magritte La Cascade (The Waterfall) (1961)

Photo: courtesy Masterworks Fine Art Gallery

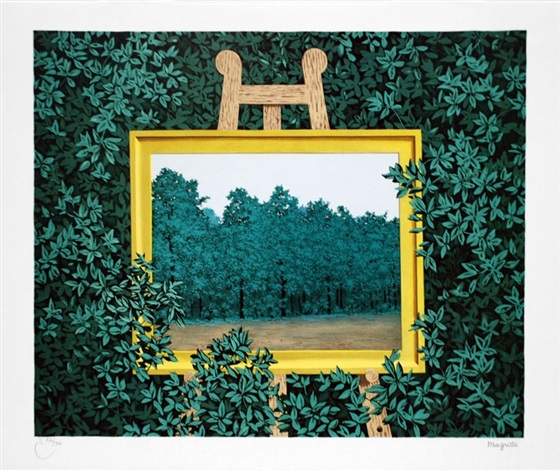

Magritte’s most famous works—in keeping with the Surrealist tradition—question the nature of reality and perception, most notably in his painting of what appears to be a pipe, This is Not a Pipe (1928–29). There is much debate as to the true meaning of this work, but the most accepted read is that this painting is not an actual pipe, but a painting of a pipe—or, rather, the idea of a pipe as represented by the artist.

“If the dream is a translation of waking life, waking life is also a translation of the dream,” he is often quoted as saying.

The Surrealist movement was made up of a variety of writers, artists, and thinkers, and as Magritte’s imagery became more sophisticated, he increasingly drew on imagery from literature, the media, and other artists’ work to create thoughtful narratives and visual puns.

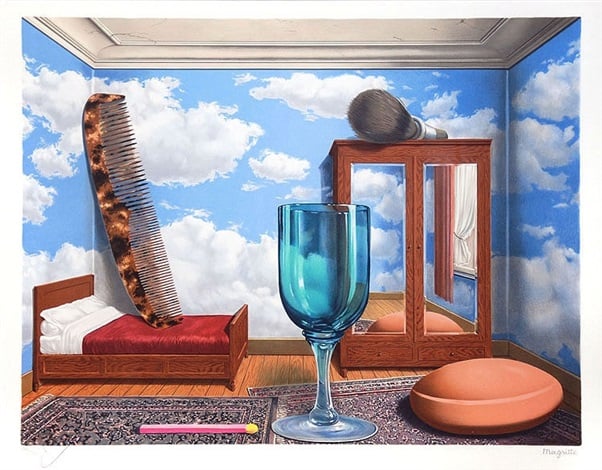

René Magritte Les Valeurs Personelles (Personal Values) (1952)

Photo: courtesy Masterworks Fine Art Gallery

“I’ve got nothing to express,” he exclaimed in an interview in 1951.“I simply search for images and I invent…only the image counts, the inexplicable and mysterious image, because all is mystery in our life.”

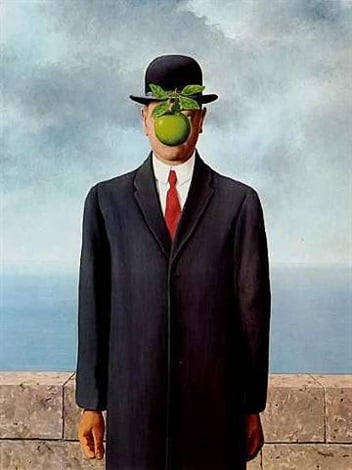

Magritte used imagery from the writings of Edgar Allen Poe, André Derain, Pablo Picasso, and the metaphysical artist Giorgio de Chirico. He also repeated his own motifs throughout his career, including the most famous, an anonymous businessman in a bowler hat. By returning to the same themes again and again, he created layered visual references and a kind of ongoing narrative.

In Belgium after the second World War—although this is when Magritte created some of his most famous works—there little money for art, and Magritte supported himself through forgery. He replicated artworks, including Picassos, and even forged banknotes in a scam he ran with his brother.

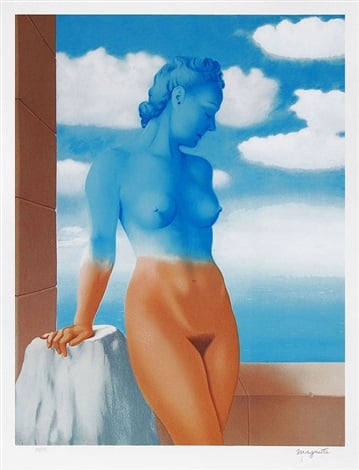

René Magritte La Magie Noir (Black Magic) (1945)

Photo: Masterworks Fine Art Gallery

It was during the 1960s that Magritte became widely recognized, and he exhibited at MoMA in New York in 1965, two years before his death at the age of 68. Magritte’s accessible painting style and clear, allegorical—sometimes borrowed—imagery has been credited with influencing the Pop Art movement. Artists who cite him as an important influence include Andy Warhol, John Baldessari, Jasper Johns, and Ed Ruscha, among others. Magritte nevertheless sought to distance himself from Pop Art.

Magritte’s work has truly entered the mainstream, and is appreciated by an audience wider than one typically enjoyed by a fine artist. His painting The Son of Man (1946) was prominently featured in the classic heist movie, The Thomas Crown Affair (1999), and in cult movie director Alejandro Jodorowsky’s avant-garde fantasy film, The Holy Mountain (1973).

More recently, a large-scale exhibition at LACMA exploring Magritte’s influence on contemporary art: “Magritte and Contemporary Art: The Treachery of Images” ran from 2006–2007. In 2013, the Museum of Modern Art dedicated another retrospective to this artist, “Magritte: The Myster of the Ordinary, 1926–1938,” featuring 80 paintings, collages, and objects.

Magritte enjoyed real fame during his lifetime, and was well-respected in his native Belgium. In honor of their native son, the comprehensive Musée Magritte opened in Brussels in 2009, with a collection of 200 works, including photography and film.

Through these and other exhibitions, Magritte’s widespread influence continues to endure.