Analysis

Does a Sotheby’s Stock Dip Signal Trouble for the Wider Economy?

Experts weigh in on what the art market tells us about economic booms and busts.

Image: Courtesy http://www.mansharamani.com/

Experts weigh in on what the art market tells us about economic booms and busts.

Philip Boroff

Sotheby’s headquarters in New York

Compared to the $24 trillion US stock market, Sotheby’s is relatively small, a public company valued at just $1.9 billion. But its stock is watched well beyond the art world. Indeed, a dip in Sotheby’s stock has an uncanny record of signaling danger in the broader economy—and the New York auctioneer’s shares are down 38 percent since June, to a three-year low.

Should we be worried? Here’s the record.

Back in October 1989, Sotheby’s shares reached a new high, fueled in part by Japanese buyers paying records for Impressionist paintings. After that milestone, the stock lost two-thirds of its value in a year. Two months after Sotheby’s peak, the Nikkei 225 stock index touched nearly 39,000 and then lost 80 percent over 13 years. Today, the Japanese benchmark remains under 20,000.

In April 1999, Sotheby’s reached another high, amid the first Internet stock mania. They it began an 80 percent descent. The rest of the market, as measured by the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index, topped out nearly a year later and dropped by half.

Sotheby’s and the S&P 500 recovered to new highs in late 2007, during the housing boom. Sotheby’s shares then collapsed, losing 90 percent. The S&P tumbled by 50 percent.

Now, Sotheby’s is down 46 percent since January 2014, while at the same time, the S&P recovered from a late summer swoon and is near a record. Is the auction house’s stock telling us that the party can’t last?

Vikram Mansharamani, author of Boombustology

Image: Courtesy http://www.mansharamani.com/

Vikram Mansharamani, a lecturer at Yale University and author of Boombustology: Spotting Financial Bubbles Before They Burst, calls Sotheby’s “a leading indicator of leading indicators of confidence.”

In an interview, Mansharamani conceded that Sotheby’s value as a predictor is reliable but “fuzzy.” Identifying bubbles requires multiple data points, he said.

But he pointed to Christie’s Nov. 9 sale of the second-most-expensive artwork at auction—Amedeo Modigliani’s painting of a nude woman, for $170.4 million—as another signal to watch. “World records are more often and more likely associated with overconfidence than mere confidence,” he said.

Amedeo Modigliani, Nu couché, 1917–18.

Courtesy Christie’s New York.

Writing a few years ago on the website of the CFA Institute, Mansharamani posited that the 1999 peak in Sotheby’s stock “is associated with the (irrational?) exuberance that telegraphed the tech bust.”Similarly, in 2007, hedge fund and private equity executives were beneficiaries of low interest rates, and they bought art at record prices, in turn driving Sotheby’s stock to a record, telegraphing the global financial crisis. And finally, “[t]he most recent peak was driven by Chinese and emerging market buyers, possibly telegraphing a Chinese and emerging markets slowdown,” he wrote at the time.

That warning, coming as it did before recent Chinese market turbulence, was prescient. But Jeff Rabin, a principal of the adviser Artvest and co-founder of the Spring Masters New York art fair, cautions against attaching too much significance to the near-record Modigliani, bought by a Chinese billionaire. “It was what one person was willing to pay for that painting on that particular day,” said Rabin, who’s a former trading executive at Barclays Global Investors.

At Business Insider, Linette Lopez persuasively argues that Sotheby’s recent stock drop is a warning that its high-end clients will get “walloped” as rising interest rates puncture a bubble of various assets, including art. Elsewhere, in a Nov. 9 conference call about third-quarter earnings, Sotheby’s chief executive Tad Smith acknowledged that demand for the “middle market” is already “sluggish.”

Sotheby’s CEO Tad Smith.

Yet there is reason to take the “Sotheby’s warning” with a grain of salt.

Given the intense competition with Christie’s for consignments, many of the company’s challenges may be of limited relevance to the economy at large. Sotheby’s has struggled to grow profits in the best of times. Chief financial officer Patrick McClymont said it was “premature” to determine whether the auctions of the estate of the company’s former chairman, Alfred Taubman, will be profitable after Sotheby’s extended guarantees of $515 million. Privately negotiated sales have been anemic since 2014.

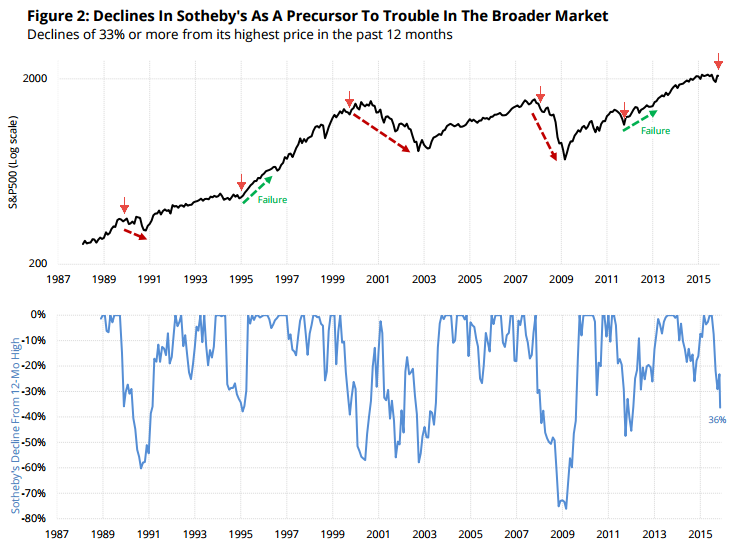

Jason Goepfert, president of Sundial Capital Research, an independent firm that seeks to apply mass psychology to financial risk management, notes that Sotheby’s shares have declined more than 33 percent five times since 1989. Three times the declines preceded large drops in the broader stock market. Twice, Sotheby’s dips failed to predict anything about the broad market. The jury is out on Sotheby’s latest tumble. (The graphs below, with U.S. stocks on top and Sotheby’s declines on bottom, are courtesy of Sundial.)

Even if stocks don’t follow Sotheby’s recent drop, the auctioneer going forward may still be a leading indicator. Goldman Sachs’s Sotheby’s analyst, Taposh Bari, forecasts that the shares, at about $29, will be unchanged in a year. He noted in a Nov. 23 report that at $2 billion, the November New York auctions at Sotheby’s and Christie’s suffered their first sequential decline since 2011. In addition, he argued, any Sotheby’s “strategic improvements” will likely be offset by “choppy art market trends, macro headwinds, competitive pressure,” and its already reasonable price relative to earnings, he wrote.

Correspondingly, Goldman’s chief U.S. equity strategist, David Kostin, forecasts that the S&P 500 will end 2016 unchanged from today. The Federal Reserve will begin to raise its benchmark interest rate in December “and continue steadily for several years,” he wrote last week. Stock prices relative to earnings will contract and offset modest earnings-per-share growth.

Goldman’s overall takeaway: Both Sotheby’s and stocks will tread water in 2016.