Art & Exhibitions

Review: Susan Philipsz at Berlin’s Hamburger Bahnhof

Alexander Forbes

For her first solo museum show in Berlin, 2010 Turner Prize winning artist Susan Philipsz has left the Hamburger Bahnhof’s sprawling central hall empty. Almost, that is. The Scottish artist has placed 24 speakers in the hall, one hung on each of the columns between the former rail station’s arches. From them, three works of music originally intended for film by mid-20th century Austrian composer Hanns Eisler play in a peculiar fashion. As in her previous works The Distant Sound (2012) and The Missing String (2012), shown at New York’s Tanya Bonakdar and at Documenta 13, respectively, Philipsz has deconstructed the compositions such that each speaker is assigned a different pitch on the chromatic scale. The three pieces, which form a nearly 40-minute loop—Prelude of a Passacaglia (1926), written for Walter Ruttmann’s Lichtspiel: Opus III (1924); Fourteen Ways to Describe Rain (1941), written for Joris Ivens’s Regen (1929); and Septet No. 2 (1947), written for but never included in Charlie Chaplin’s The Circus (1928) on account of Eisler’s deportation from the US—circulate the hall in a seemingly random but in fact strictly regulated manner.

The installation, titled Part File Score (2014), reduces much of the context placed within or around those previous two efforts, however. At Documenta the notes were played over loudspeakers distributed throughout Kassel’s very much in-use Hauptbahnhof; at Bonakdar, train sounds from the New York subway and various rail hubs in Berlin injected themselves into the music.

Here, save footfall, the hall turns silent between the violinist, cellist, pianist, and trumpeter’s notes. It leaves one simply with Philipsz self-imposed dialectic: sound and architecture, Eisler’s film scores, and a disused train hall behaving as a sleekly polished museum space.

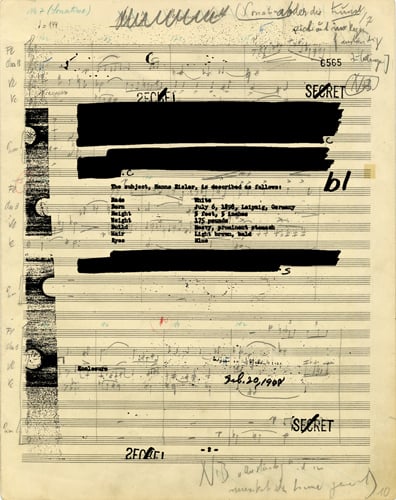

That’s not to say no visual work is on view. 12 digital print and silkscreen works hang in the hall’s dual arcades and document the FBI’s surveillance of Eisler during his exile in the US from 1938 to 1946 due to suspicions of his Communist sympathies. Various declassified agency records about both his personal and artistic activities are superimposed onto his music’s scores. Their link to the sound installation goes beyond the biographical, however. Moving from one work to the next with back turned to the hall, the sound’s constant movement becomes unnerving, as if it were embodied by Eisler’s watchers, their names now redacted with thick, black bars. Yet particularly when one stands still, the sound’s movement becomes hypnotic. The one-note-per-speaker structure never becomes explicitly apparent. But head-swiveling attempts to pinpoint each sounds’ origins do subside in the same way that curiosity about the content of distant, hissing whispers does.

Susan Philipsz, Part File Score (2014).

Photo: © Courtesy the artist, Isabella Bortolozzi Galerie, Berlin, Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York.

Philipsz’s method of placing each of the notes at equally spaced intervals throughout the hall suits its subject well, from a theoretical point of view. It spatializes the very concept of the 12-tone technique developed by Eisler’s mentor, Arnold Schoenberg. Schoenberg’s system proposes a radical rethinking of musical composition in which each note on the chromatic scale receives as equal play as possible within the piece, thus also eliminating the central element of classical composition: key. Philipsz offers this to her listeners, giving each an equally unequal grasp of the orchestral whole. More important, by placing the listener within the piece, she eliminates the final hierarchical element of music appreciation.

Where Schoenberg’s symphonies accosted the audience with the cacophony of the industrial age, Eisler’s employ of the 12-tone method in film, theater, and radio drama sublimated its whip of alienation into the everyday. Philipsz takes the move one step further. She wrests the listener from his velvet-clad chair on the mezzanine or reclined La-Z-Boy at home, throwing him into the orchestra pit: she implicates him in the deed. However, despite its anti-hierarchical efforts, agency remains at arms length, visible but not actionable. If Schoenberg was the factory floor and Eisler (in original form) the cubicale in a Miesian tower, Philipsz is the couch-bound independent contractor.