In the days leading up to an evening sale, Sara Friedlander, who is deputy chairman of Post-War and Contemporary Art at Christie’s, can expect a half-mad frenzy of a week.

Last-chance viewings. Phone tag across continents. Slinging in pre-bids from billionaires. Squeezing in an impossible number of breakfasts and lunches. And coordinating a team of specialists with their eyes on hot lots in the day sales.

Often, it pays off—in May 2018, Friedlander was on the phone with the client who purchased Robert Rauschenberg’s Buffalo II (1964) for $88.8 million, setting a new high-water mark for the artist.

But this year’s pre-sale routine was a bit different—and not just because Friedlander has a six-month-old. Instead of your typical May gigaweek, Christie’s, on July 10, pulled off a hybrid digital/physical extravaganza called “ONE: A Global Sale of the 20th Century,” coordinated between its New York, Hong Kong, London, and Paris offices.

It was an experiment: Bidders usually just feet away from eight-figure artworks raised pixilated paddles through the magic of the internet, putting tens of million of US and Hong Kong dollars and euros and pounds on the line for works they had maybe never seen in person. When the experiment involves a Brice Marden that Christie’s hoped would demolish the artist’s former record—estimated between $28 million and $35 million—there’s a lot on the line. (Spoiler alert: It demolished it.)

Friedlander invited a reporter to tag along—well, remotely tag along, via constant texting (this reopening thing comes in phases, people)—as she ran through meetings and appointments to prepare for an unprecedented event.

Friedlander avec bebe. All photos courtesy Sara Friedlander.

6:00 a.m.: Early-Bird Special

Friedlander pressed that she’s an early riser—but not necessarily because there were hundreds of millions of dollars of art for sale in a few days.

“I’m up at 6 a.m., which, given that I have a six-month-old baby, I consider lucky,” she said. “Since it’s sale week and I’ve been going nonstop, my four-year-old daughter is at her grandparents. For this I’m also lucky. If anyone has a better parenting tip than shipping your child off, I’m all ears.”

Once up, there’s little time for a turbo-charged, eye-opening spin on the Peleton or a freshly pressed green juice. You know what there is time for? Business.

“Because of the truly global nature of our sale, I’m speaking to colleagues and clients across multiple time zones,” she said. “It’s the end of the day in Hong Kong, so I’ve already missed a lot.”

And there’s no better early-morning one-two punch than the combo of cross-continent telecommunication and strong java.

“This person needs stimulants ASAP in the form of her phone and caffeine,” she said. “I consider both bad habits that I’m trying to kick, but not today.”

The best bagel in New York, and the world.

7:00 a.m.: Good Bagels and Cecily Brown

First stop is Absolute Bagels, whose specialty Friedlander proclaims is the best in the world—“and I have authority here as an Upper West Sider,” she added. Bagel and iced coffee secured, she zipped in her car through traffic toward Rockefeller Center, where she rushed to get to a new kind of pre-auction meeting: the tech rehearsal.

“If you think you read that wrong you didn’t,” she said. “It’s a whole new world of videos and broadcasting.”

After asking her sister to leave an auction-night dress for her with her doorman—”I haven’t been to the dry cleaners in months”—a London client called about the Cecily Brown.

“I tell him I’ll know more after the meeting this afternoon because, these days, no one tells you anything until an hour before the sale,” she said. “But I can share it’s one of her best paintings to come to market, and I remind him he’s been looking for a very long time. I then spill the ice coffee all over today’s dress.”

Frank Stella being handled by the handlers.

10:00 a.m.: Stella! Stella!

Friedlander walked to a viewing room to check out a work, and found herself standing in front of Frank Stella’s black-gray and white alkyd-on-canvas painting Sharpeville. She told me that it absolutely has to be seen in person. (I’m just looking at it through a phone and it looks pretty great.)

A client, mulling a bid, had come in to get briefed on the painting—the only large-format grayscale Stella work from 1962 in private hands—by a conservator.

“I’ve Facetimed with paintings like the best of them for the past four months, but nothing ever could replace a real human standing in front of a real painting IRL, which is why this week has been particularly thrilling,” she said.

Burgers require masks to come off.

12:00 p.m.: Half a Power Lunch

Dipping out of the Christie’s citadel, Friedlander went to meet a client for lunch—burgers for both—hoping to dish on non-work topics and gossip. Alas, it was pretty much strictly business, as talk centered on bidding strategy in the evening, choice lots in the day sale, all that.

“My phone doesn’t stop buzzing and fortunately neither does his, so I’m afraid this lunch has become more burger and ‘How high do you want to go on that one?’ and less ‘How’s your life?’ which is the sad reality of today,” she said. “We signed the check after 27 minutes.”

Still, Friedlander said she tries to distill her work strategy down to the essentials, mostly working with a handful of trusted clients.

“Someone once told me you only need to do business with five people, and it’s sort of true that I speak to the same five people every day,” she said. “Plus my father, and my best friend in LA.”

The desk setup.

12:30 p.m.: Pump It Up

“We interrupt this regularly scheduled programming to pump in my office,” Friedlander said. “I work with very cool moms (and dads) at Christie’s who all understand the realities of feeding a child. I’d love to tell you I use this 10 minutes alone to meditate but I’m still on my phone sending condition reports to clients.”

Case in point: while talking to her sister about the dress, a client texts Friedlander to say he’s pulling a bid on one lot, but shifting to another.

“I panic, but this is how it goes right now,” she said.

Right then, a New York Times push notification flashed on her phone about New York schools reopening—sort of—in the fall.

“More panic,” she said.

“Sorry you can’t see the painting but that’s why it’s PRIVATE sales!”

2 p.m.: Private Victory

The afternoon started with a meeting—masks-on, of course, for those on site in New York—to gauge how serious certain clients were about kicking in bids on certain lots.

“We discuss who is on which lot, or at least what we know,” she said. “This is the time where I wonder how much is really in our control.”

Suddenly, the front desk pinged Friedlander to say a client had arrived early, so, mask on, she beelined to the lobby, organizing the viewing on the run. That’s because, instead of checking out an auction lot that’s already installed, the client wanted to look at a work on offer privately that they saw prior to the shutdown.

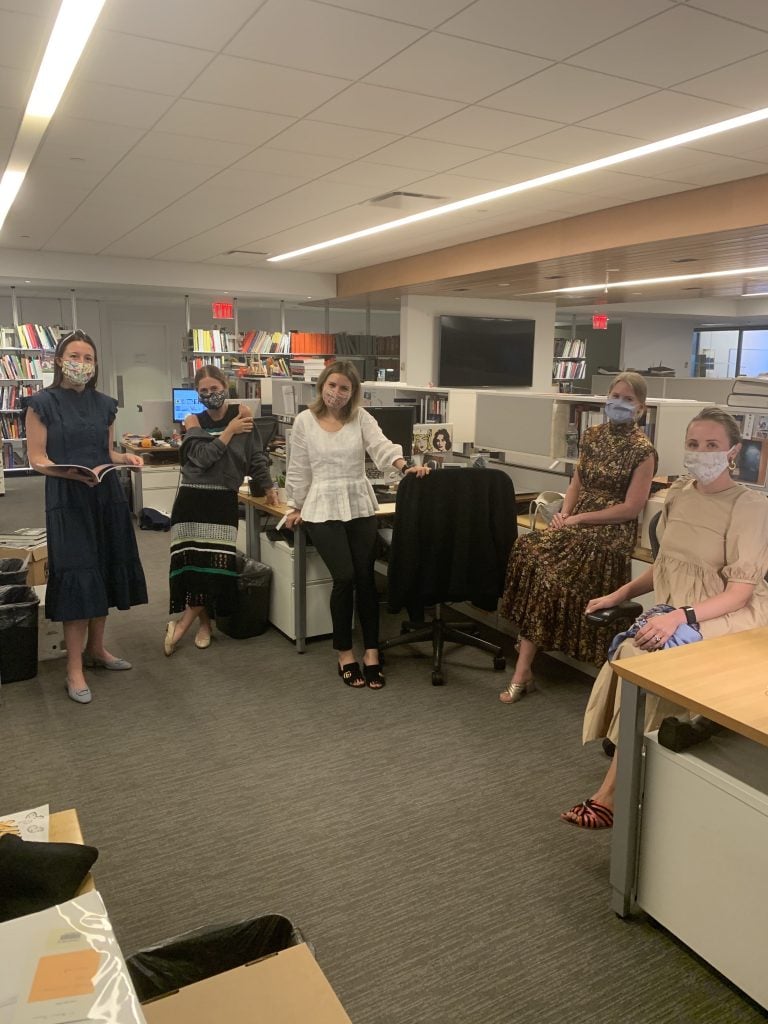

The Christie’s sales team getting ready for a landmark sale. Photo courtesy Sara Friedlander.

“Fortunately, it’s still on site,” Friedlander explained. “I suggested they walk around while I frantically called an art handler to bring the work upstairs and have it lit in a viewing room. Ten minutes later, it’s on the wall.”

But Freidlander could not get any hints about how the collector, whose face was covered, felt about the painting.

“They’re standing in front of it but I can’t read their expression because of their mask!” she said. “I wonder how long this new normal will be, and if it’s possible to read people’s eyes or body language without seeing their whole face. Does she like it? Is it as she remembered it all those months ago?”

The fears were overblown—the collector bought the work.

“This’ll mean they aren’t bidders this week, but at least they are a buyer of this painting today,” she said. “I guess there are some things I can control.”

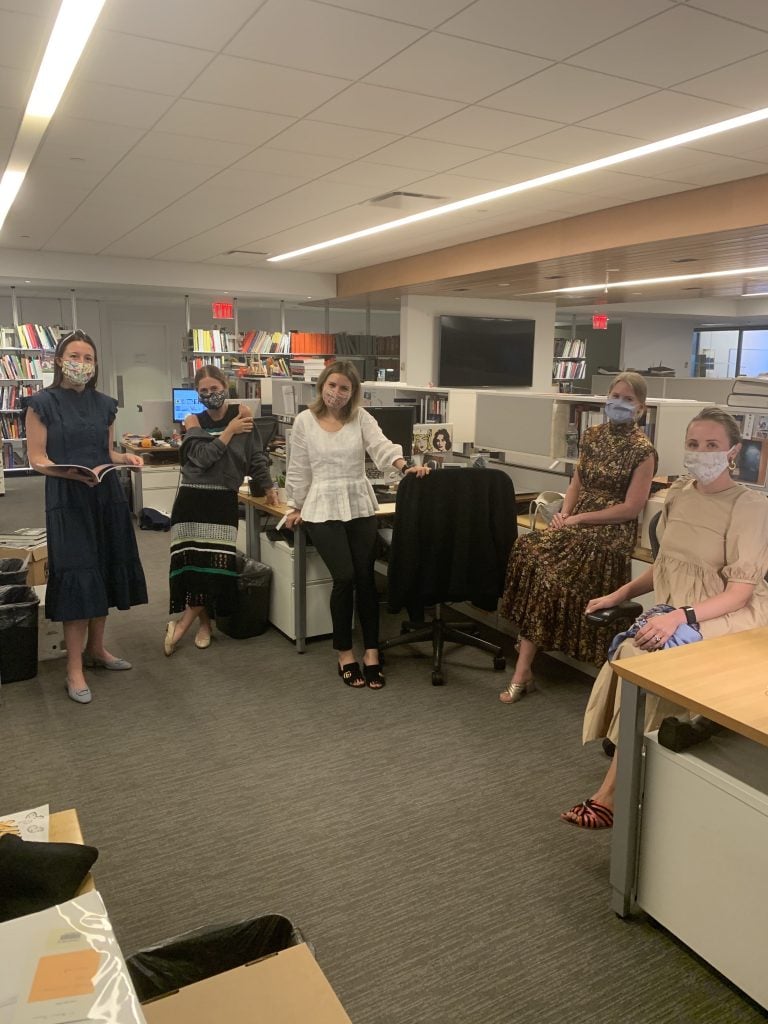

A murderer’s row of contemporary art specialists. In masks.

3:30 p.m.: Hard Day’s Work on a Day Sale

With no appointments until 5 p.m., Friedlander booked it up to the top floor of HQ to chat with the team in charge of the day sales.

“Let me tell you, these girls RULE and are among my favorite people to work with at Christie’s,” she said. “The hustle is fierce. Katie and I discuss the subject of the Titus Kaphar painting and Rachael reminds me to call my client for the Guston.”

And actually working with other humans in a real place is clearly still a novelty.

“Marc Porter comes to my office and I want to cry I’ve missed him so much,” she said. “Alex Rotter calls to me across the hall.”

Rotter’s update: His client was mulling accepting Friedlander’s client’s offer. Deals, deals, deals!

David Hammons, Untitled (2004).

5:00 p.m.: Follow the Money

More clients arrived, this time to see the wonderful David Hammons rock head sculpture featured in the sale, and naturally discussions led to incredible amounts of Hammons’s work at MoMA. As the word “MoMA” hovered in the air, Friedlander got “a pang of longing to run over there and visit.” Can’t do that, alas.

And then she received a text from a colleague asking if she had a lead on an Alice Neel painting—and a chase scene commenced! But Friedlander was also reminded that, oh, right, she needed to call another client about an Emma Amos painting. And then another client was on the horn asking about the condition of a work she bought in London—perhaps she’d be interested in a choice offering from the day sale?

And then, an interruption from on high—Friedlander’s father was calling.

“He wants to know if I’ve ordered the new Philip Guston catalogue and read Glenn Ligon’s essay,” she said. “I tell him the catalogue has arrived but still wrapped in plastic and I plan to read Glenn next week.” There’s a lot going on, dad!

A bookshelf that would look good in the background of a Zoom call, which is what I think when I see bookshelves now.

6:30 p.m.: Babies and Books

After leaving Rock Center, Friendlander made another zip through Manhattan behind the wheel—this time to rush home to feed her son Izzy. She had a few more post-home items on the agenda. A client was asking about the Jasper Johns in the sale, so after Izzy’s dinner, Friedlander scoured the shelf for the catalogue for “GRAY,” the 2007 retrospective at the Art Institute of Chicago.

“Books are an obsession and as soon as I get home and put the baby to sleep, I go to my shelf,” she said.

A Facetime with a friend—one of Friedlander’s aforementioned Top-Five People—provided a kind of sense of normalcy, or at least a reminder that people are still buying.

“Normally she’d be at the view in our galleries multiple times with clients, but this season she’s out of town watching from afar,” Friedlander said.

“It’s surreal to think how much is so out of sorts right now, and yet how normal some things are. People see something online or I call a client to recommend something I feel they should buy. They like it. They ask questions. They bid. Or they don’t. I wonder what it all means. I wonder what I’ll have for dinner. That panicky feeling sets in again. And then my phone buzzes.”

Jill Kraus, Naima Keith, Sara Friedlander, Steve Henry at the CalArts Art Benefit—one of the jet-set parties that do not exist at the moment.Photo: Aria Isadora/ BFA NYC

9:00 p.m.: Bedtime for Jetsetting

Friedlander was just a few minutes into WhatsApping friends in Hong Kong and suddenly: “I miss airplanes.” Don’t we all! But she did admit that perhaps a spring season without all of the socializing and jetsetting might have been a good reset.

“It’s wonderful how many people I’ve actually seen past week—how the art market ticks on without the usual dinners and galas and ticketed evening sales,” she said. “Maybe we’ve gotten back to something that’s been missing for a long time. Less catalogues equal less waste. Our carbon footprint is lighter. Will it ever go back to the way it was? Should it?”

And with that thought, she rinsed her coffee mug from the morning, and left her phones (plural) in the kitchen.

2:30 a.m.: Auctions Never Sleep

The little baby all of a sudden started crying, waking up Friedlander—and then stopped immediately, falling back into slumber.

“But now I’m awake,” she said, texting in the late-night transmission. “I go back to the Johns catalogue. In Hong Kong lunch is already finished.”