In 2010, the Atlanta-based collector William Arnett founded Souls Grown Deep, an influential nonprofit dedicated to promoting the work of lesser-known, largely self-taught artists from the southeastern United States. Since then, Arnett has donated more than 1,100 works by more than 160 artists from his personal collection to the organization—a significant number of which have since been acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the High Museum of Art, the Brooklyn Museum, and other major institutions.

Yet Arnett’s gift only accounted for roughly half of his massive collection. Hundreds of other artworks, including numerous pieces by Thornton Dial, Lonnie Holley, and Mary T. Smith, remained in the family’s hands.

Now, a selection of works from that collection is being offered for sale through a gallery exhibition for the first time.

“A Different Mountain: Selected Works from the Arnett Collection,” which opens Thursday and is on view through January 11 at Marlborough in New York, brings together 75 paintings, sculptures, and works on paper by nine artists from the South, as well as a series of patchwork quilts made by generations of African American women.

Joe Minter, Springtime in America (2019). Photo: Fredrik and Erin Brauer.

“A Different Mountain” was organized by Arnett’s sons, Paul and Matt Arnett, who have long worked with their father to promote these artists’ work—and, specifically, to challenge limiting terms like “outsider art” and “folk art” that often constrain the way the art world views artists without formal training.

This isn’t the first time William Arnett has let go of pieces from his collection. A voracious collector of Chinese and Indian art in addition to that of the Southeastern US, Artnett has, over the years, sold work privately to fund other acquisitions. But he has never consigned so much at one time through a gallery.

Part of the family’s decision to bring the art into the gallery system now is precisely because that system has been so traditionally unwelcoming to the kind of artists the Artnetts collect. “When we think of art history, we know the biographies of the great artists, we know what their personalities were like and what they said and those things are part of our understanding of their work,” Paul says. “With this type of art, that tends to get flattened out. Because of our tendency to otherize them as individuals, the artists become very two-dimensional.”

The goal of the show—and of Souls Grown Deep—is to “make the people as three dimensional as possible,” Paul adds. “Putting their art on an equal footing with others—that’s one way of doing it.”

Top: Matt and William Arnett. Bottom: Paul Arnett.

For the show, the Arnetts selected work that “could be easily digested by a contemporary art audience” without compromising its unique context or reaffirming its perceived outsider status.

It isn’t an easy needle to thread. “If there was an easy answer, I think we would have found it a long time ago,” Paul says. “Part of the glory of this work is that it’s so resistant to easy definitions. In many ways the artists really are outsiders in this context, but that’s certainly not their essence.”

The show includes sculptures by Holley, Hawkins Bolden, and Joe Minter—all created from everyday objects such as pots, hoses, and belts—as well as paintings by Smith, Dial, and Ronald Lockett (Dial’s cousin), who similarly turned to found material such as cardboard and corrugated tin as canvas.

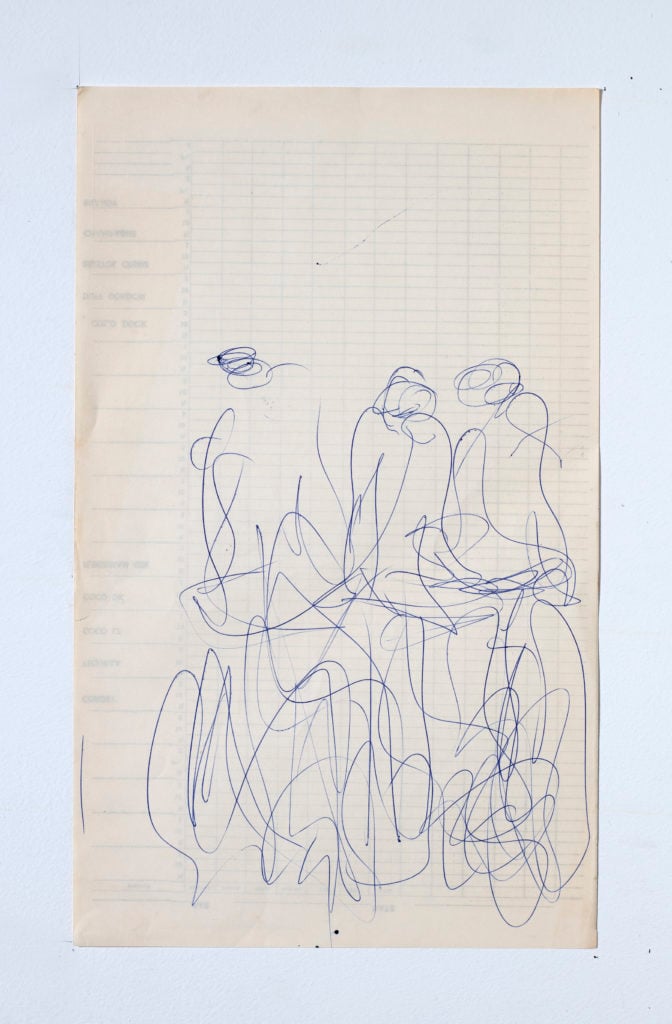

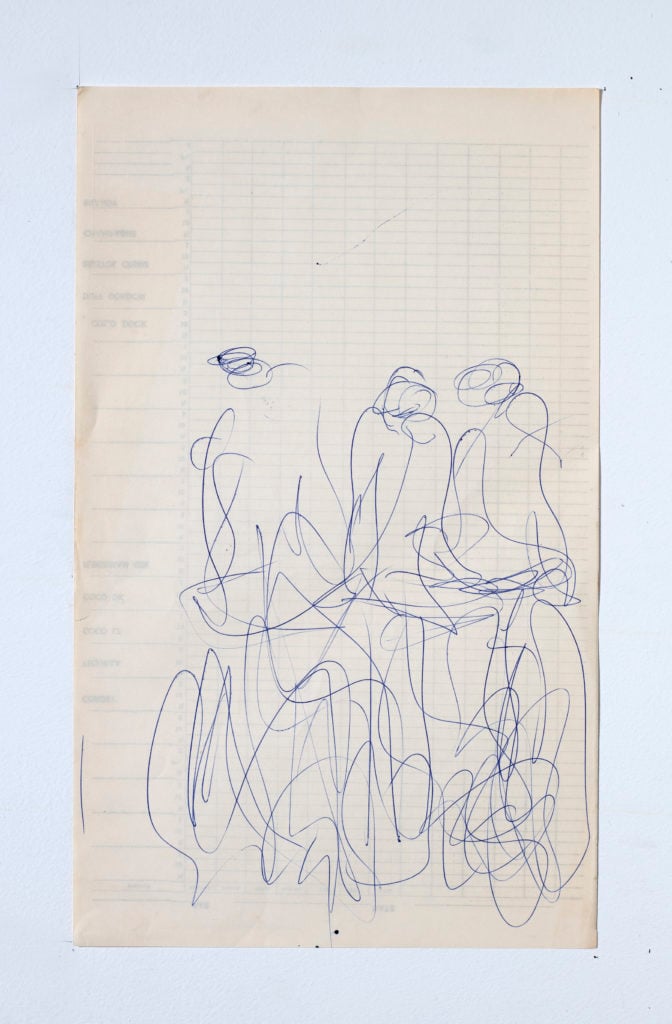

A series of minimal drawings by Purvis Young—a welcomed surprise, the Arnetts note, for those familiar with the artist’s better-known paintings of tightly packed country scenes—will accompany a group of small, unfired clay head sculptures by James “Son” Thomas, a blues musician, gravedigger, and sculptor from Mississippi. Elaborate quilts by various artists are interspersed throughout.

Purvis Young, Chaos. (1980). Photo: Fredrik and Erin Brauer.

The works range in price from $5,000 to $300,000, a representative from the gallery confirmed.

“I really hope this exhibition will disorient people,” Paul says. “You might not be sure what it is if you don’t already know. You wouldn’t necessarily identify the people who made it as self-taught; you wouldn’t necessarily identify them as having a regional specificity or being African American.”

James “Son” Thomas, Untitled (c. 1980s). Photo: Fredrik and Erin Brauer.

Ronald Lockett, Traps (1990). Photo: Fredrik and Erin Brauer.

Purvis Young, Untitled (c. 1970s). Photo: Fredrik and Erin Brauer.

Hawkins Bolden, Untitled (Seated figure) (c. 1980s. Photo: Fredrik and Erin Brauer.

Mary T. Smith, Untitled (1980). Photo: Fredrik and Erin Brauer.

Lonnie Holley, Fighting for the Harvest (2018). Photo: Fredrik and Erin Brauer.

“A Different Mountain: Selected Works from The Arnett Collection” is on view at Marlborough through January 11, 2020 and will be accompanied by a catalogue co-written by Paul and Matthew Arnett.