Archaeology & History

Students Make Major Breakthrough in Use of A.I. to Decipher Ancient Scrolls

“This is a complete game-changer,” experts say, as we get one step closer to rediscovering long lost ancient texts.

“This is a complete game-changer,” experts say, as we get one step closer to rediscovering long lost ancient texts.

Jo Lawson-Tancred

An international trio of students has made a major breakthrough in the use of A.I. to decipher the texts hidden within a set of ancient scrolls that were carbonized by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 C.E. Youssef Nader from Germany, Luke Farritor from the U.S., and Julian Schilliger from Switzerland, have jointly won the whopping $700,000 grand prize for managing to read several passages containing 2,000 ancient Greek letters from one scroll.

“This is a complete game-changer,” announced the papyrologist Robert Fowler, according to the Guardian. “There are hundreds of these scrolls waiting to be read.” He added that the discovery has allowed scholars to speculate that the scroll in question might contain a text by the philosopher Philodemus of Gadara, which is the kind of insight that would have seemed impossible just a decade ago.

The students were competitors in the Vesuvius Challenge, which was launched last year by the University of Kentucky computer scientist Brent Seales to encourage A.I. experts the world over to get involved with the unique challenge of deciphering these long lost ancient texts.

“The adrenaline rush is what kept us going,” said Youssef. “It meant working 20-something hours a day. I didn’t know when one day ended and the next day started.”

The historic eruption of 79 C.E. covered Pompeii and the nearby town of Herculaneum in a layer of ash, accidentally preserving a moment in time for centuries to come. When archaeologists discovered the site in 1754, they uncovered a palatial home in Herculaneum complete with an ancient library full of over 1,000 papyrus scrolls that had been carbonized by the exceedingly hot ash and pumice. The shelves were believed to contain Epicurean philosophical texts in both Roman and Greek that once belonged to Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus, Julius Caesar’s father-in-law.

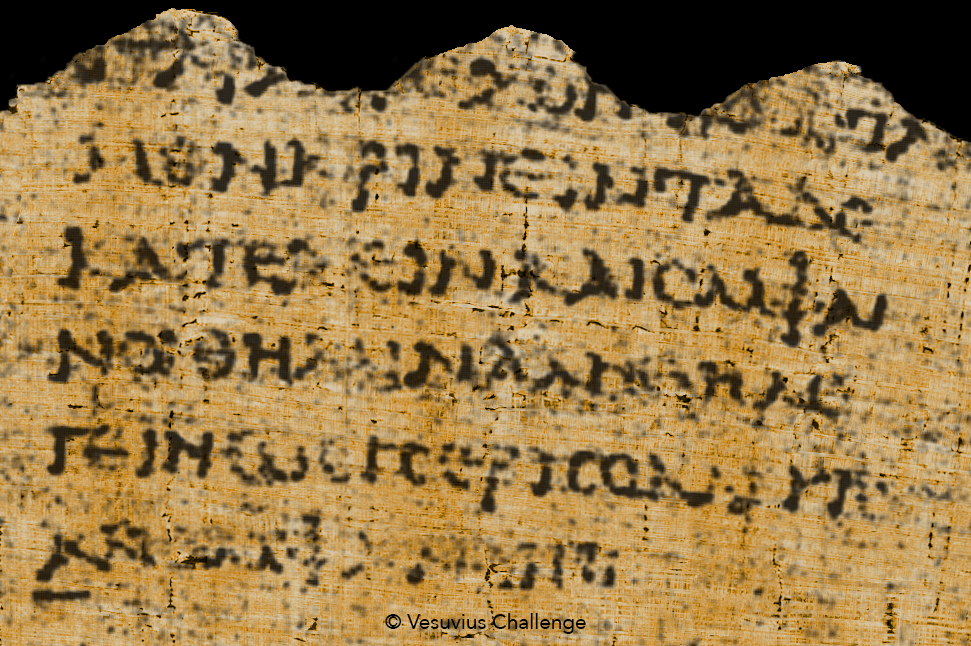

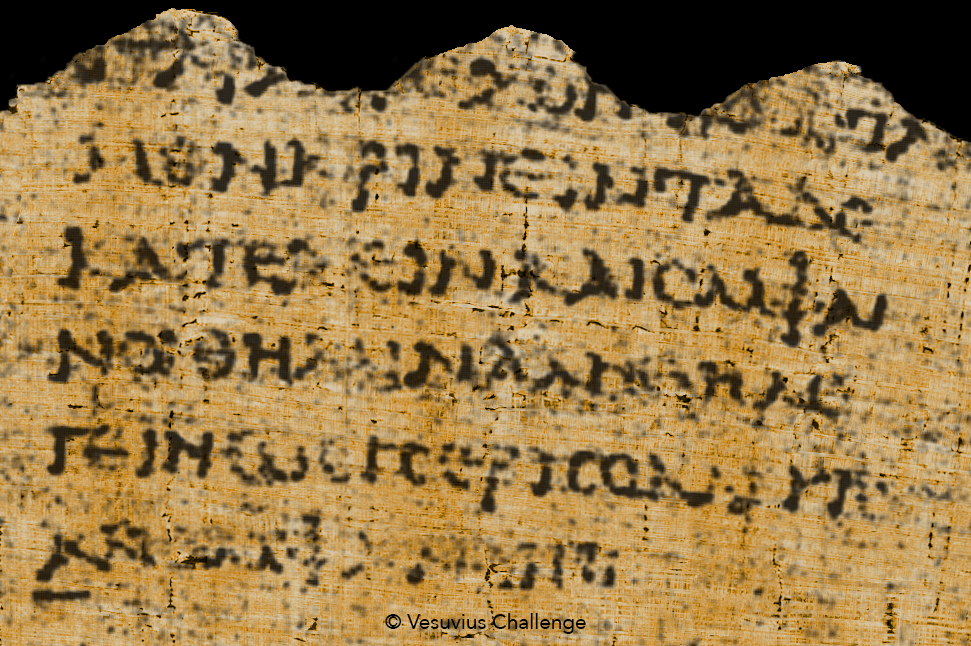

A 2,000-year-old Herculaneum scroll. Photo by the Digital Restoration Initiative.

Archaeologists have long been tantalized by the possibility of cracking open these texts, since it is highly likely that at least some would have been otherwise lost to the passage of time. If they can be recovered, it would constitute a groundbreaking revelation for classicists. Sadly, the charred scrolls have proven much too fragile to unravel and several attempts over the years have resulted in the priceless objects being damaged or falling to pieces.

That is, until recently. In the past decade, scientists have succeeded in producing highly sophisticated, three-dimensional CT scans of the scrolls. Thanks to the powers of A.I. and computer vision, Seales and his team of researchers at the University of Kentucky have been able to straighten out or “virtually unwrap” these tightly layered scrolls. They then trained algorithms to detect the ink, which did not show up clearly on scans.

Once the 2,000-year-old text could be extracted, the Vesuvius Challenge was launched so that a wider net of scholars and computer scientists could contribute to the global effort to decode these scrolls’ secrets. Last fall, one of the trio of students, Luke Farritor, won $40,000 for deciphering the first word from the charred scrolls. That word was “porphyras,” which in ancient Greek means “purple.”

The scroll that has now been partially deciphered is apparently a treatise on the pleasures to be derived from music and food. “In the case of food, we do not right away believe things that are scarce to be absolutely more pleasant than those which are abundant,” the ancient writer mused.

Even though the top prize has now been awarded, the Vesuvius Challenge will continue with a new goal of reading 85 percent of the partially deciphered scroll. It has also announced a new $100,000 grand prize for the first team that is able to read at least 90 percent of all four scrolls that have so far been scanned.

With time, researchers hope to fine-tune the various processes involved in scanning, virtually unwrapping, and detecting the ink on the hundreds more scrolls that await decoding. One day, we should be able to read the entire ancient library.