Politics

‘We Take Ownership and Responsibility’: Indonesian Collective Taring Padi Reflects on the Controversy Over Their Art That Paralyzed Documenta

Members of the group discuss blind spots, censorship, and the need for dialogue.

Members of the group discuss blind spots, censorship, and the need for dialogue.

Kate Brown

Documenta tends to be a fire-starter. Every five years, the German art show arrives as a big statement about the state of art now, and it has often inspired its fair share of controversy. Still, the blowup over the 2022 edition has been like no other.

Since January, the curators, Indonesian collective Ruangrupa, along with their artistic team and a few participants, have been battling allegations about their positions on Israel, including accusations of antisemitism, as they worked towards a publicly funded exhibition in a country that holds a particularly weighty responsibility towards Jewish communities and Israel. The German media asked tough questions: Why, for instance, were there were no Jewish-Israeli artists in a show that focuses so heavily on the Middle East and Global South? Ruangrupa and the show’s artists, in turn, felt singled out, under general suspicion, and attacked (a venue of a Palestinian collective was vandalized). Dialogue seemed difficult to establish. And that was all before viewers noted two characters in a work by Indonesian collective Taring Padi that use antisemitic tropes, just days after Documenta opened to the public. The work was covered up and then removed. The general director of the show resigned.

The members of Taring Padi have had a lot to work through since then. The group, established in the late 1990s to express solidarity with oppressed peoples, has been shaken to its core. I spoke with two members of its members, Alexander Supartono and Hestu Nugroho, about their blind spots, the tricky question of censorship, and how to own and learn from a grave mistake—as well as how the group is moving forward.

Taring Padi. Courtesy Taring Padi

You are one of the most prominent collectives to come out of Indonesia, along with Ruangrupa, but you are very different.

Alexander Supartono: We are older than Ruangrupa. Around that time in Indonesia, there were many art collectives springing up following the new freedom after the fall of Suharto. We are both prominent collectives because we endured and still exist after 20-odd years. We have a different character and different ideology: Ruangrupa is more urban and cutting-edge and Taring Padi is more traditional and typical left-wing. Although we know and respect each other, we hardly worked together until Documenta 15.

Can you share a bit about your collective—where and why was it founded?

Hestu Nugroho: We started before the Post-Suharto reformation, and back then we had not yet decided to become Taring Padi as such. We made a declaration in December 1998. But most of us are from the same art school—the Indonesian Institute of the Arts. We organized events and discussions from within the underground scene. Nearly 100 people have been involved in some way in Taring Padi over the years.

AS: The best way to understand Taring Padi as a group of individuals is two words: friendship and ideology. We work to materialize or express our ideologies, and while we are working, friendships develop which in turn nurture our identity. Our existence is sustained by a dynamic between these two elements.

A view of Taring Padi’s work at Hallenbad Ost at Documenta 15. Photo: Ina Fassbender/AFP via Getty Images

Thinking about that axis, has your dynamic changed since this whole scandal emerged around Documenta 15 in June? How does the communication within the group evolve in the wake of such an intense situation?

AS: Within that friendship and ideology is learning. This aspect has been key in our very intense discussions since the controversy. Belajar bersama sama, or learning together, is very important to us.

HN: It is also about learning without worrying about genders, borders, or age. We still talk about these aspects and religion and ethnicities, but we do not let it define the conversation. We are still very open as a collective.

Your project at Documenta 15 was called “Flame of Solidarity: First they came for them, then they came for us.” The second part is a reference to Martin Niemöller’s poem that reflects on the Holocaust. It touches on what you said in a way, in regards to this interconnectedness beyond identity. Could you explain more?

HN: I am still thinking about that, but [the reference] is not out of the blue. The point is that all of us could be counted as a victim of the global system.

AS: The title of our overall presentation at Documenta 15 is “The Flame of Solidarity.” We asked ourselves whether to accept the invitation for the exhibition, and why. We decided to take it and use it as a platform for campaigning—for farmers who lost their lands, for example. We wanted to bring what we have been working on with diverse communities for the past 20 years to the art world’s international stage.

Why is solidarity more urgent than ever? If you do not build it up within the global network—and the Global South network—they will come for us. We have seen that. We already witnessed how liberal and capitalist systems affected life for fishermen and farmers, for example. That is what Niemöller’s quote meant to us and how we came to it.

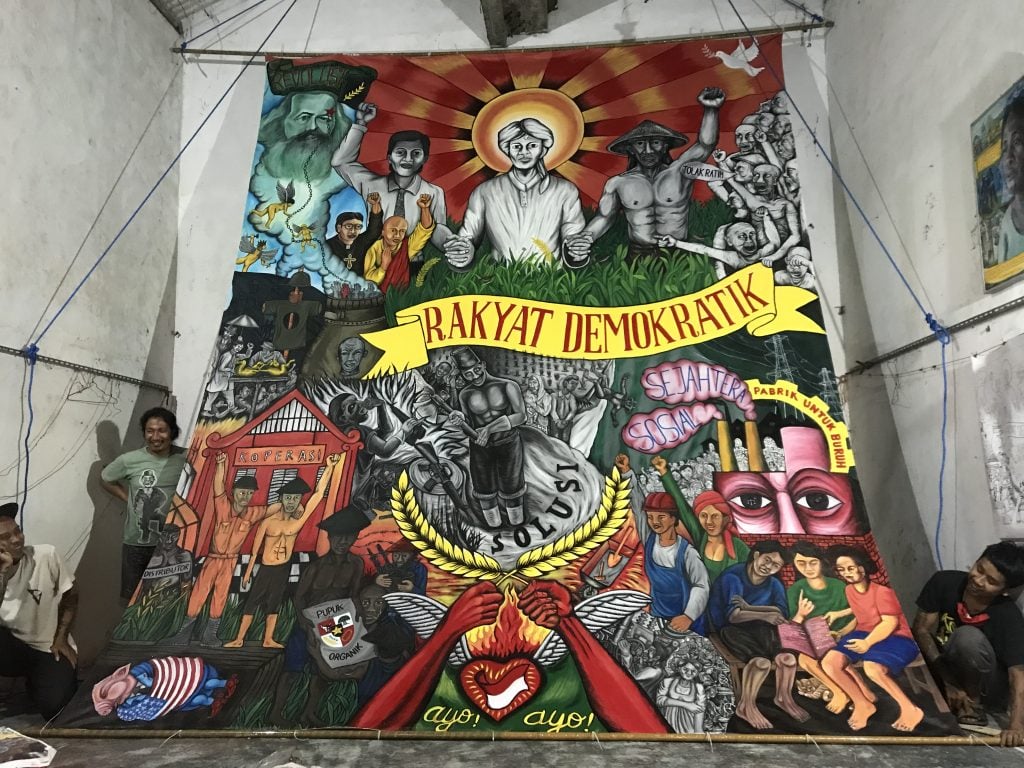

Rakyat Demokratik (‘People’s Democracy’) was made in 1998 after the fall of Suharto. It was burnt down in 1999 by a group of Islam fundamentalists. Taring Padi made a replica in 2021 that is presented at Documenta 15. Courtesy Taring Padi

Germany has a particular responsibility when it comes to combatting antisemitism. Do you feel that there should have been more support to help you translate and understand the local context that you were working in during Documenta?

AS: We do not want to blame anybody. We need to educate ourselves because we are not that unfamiliar with the general context. I know the Goethe Institute well in Jakarta and many members of Taring Padi have German partners, like Hestu. We should have known about this, and that was the mistake. It was utterly unnecessary and sloppy. We take responsibility for that and we go back to our principles about working together and learning together.

Now we work on how to move forward. It should be added, though, that this mistake is singular. Because examination of our works—hundreds of them—revealed there isn’t anything else that might trigger antisemitic readings.

We obviously overlooked the progressive element within the Jewish community in the Israeli state or anywhere. We try to get in touch with them because that is our working principle: We always try to go to the community and have direct contact. You will soon see that something is happening before the end of Documenta 15 in this regard.

HN: 90 percent of Indonesia is Muslim, but inside of that community are a lot of layers and a lot of different ideologies. There are a lot of layers in the Jewish community as well.

Courtesy Taring Padi

What are you focusing on as a group in your conversations?

AS: We denounce fascism from the bottom of our hearts. What hurt us the most was being seen as antisemitic, because we have tried our best since the very beginning of our founding to be very respectful of everyone.

When we try to make our cardboard puppets to show solidarity with the victims of violence in Myanmar and Palestine, for example, some of us ask questions: Do we truly know about that? Have we been in touch? What experience do we have with people in these places apart from what we know from the media? In the wake of this scandal, we want to look more at these questions.

Why is it that the angle that has come up through this experience not been more popularly discussed? We don’t know as much about these issues as we should.

Similarly, others can stand to learn more about the complexities within Indonesia, the issue of antisemitism here, which is alive in the present day through Islamic fundamentalists. This is the very same group that sees us as their enemy. The same people who campaign on antisemitic ideas also burn our banners and attack us. This complex socio-political situation in Indonesia needs to be understood as well. I am quite optimistic that we can do something with this issue and that we will.

HN: Yes, and we are learning from our mistakes. We apologize—but we will not stop there. As part of apologizing, we will keep learning and working.

AS: It is also important to say that we are not just being apologetic because of the pressure. Some people from the [political] right said that we are just reacting to pressure, but we are not. We couldn’t care less about that. We know that art is a political tool and we take that on with responsibility. It is within that context that we want to continue working.

HN: It is also important that we respect the lumbung community [of artist collectives brought together by Ruangrupa for Documenta 15]. Had we just stood by our work and disagreed about its removal, we would have risked also the sustainability of the entire Documenta 15 and all the groups working there.

The artwork 1000 wayang kardus by Taring Padi at Documenta 15. Photo by Thomas Lohnes/Getty Images.

Can you share more about the decision process behind the removal?

AS: When Hestu, myself, and another member of Taring Padi came into that meeting with Ruangrupa and the directors of Documenta on that Monday in June, we all had a heated debate about whether we should cover up the work or not. Some individuals were very upset about the covering up of the work and threatened to walk out of the show. When one of the Documenta heads said that they did not know whether they would have a job or not the following day, immediately it also became clear what we had to do. We cannot put someone’s livelihood at risk because of our work. Our work is about humanity.

HN: The black banner was a symbol of mourning, a first statement.

You said it was a monument of mourning to the impossibility of dialogue. It sounds like you are trying to find this dialogue now. It is interesting to hear because this is something we have heard from other relevant parties. Meron Mendel, director of the Anne Frank Education Center who was brought on as an external advisor (he ended up resigning), also said it has been hard to have dialogue. I had heard the same language even before this all happened from Jewish people in the art community in Germany. Why was it so hard, from your perspective?

AS: That is very interesting that you hear this as well. We want to talk. After the decision was made to cover the work, there were no further discussions. We were informed in an email from the board that they unanimously decided that the work was going to be taken down in two hours’ time.

We hear things from here and there, but dialogue continues to not happen. Now we are in the process of creating a dialogue ourselves, without Documenta. We hope they will participate and maybe they are trying without any success elsewhere without informing us. But let’s not blame anybody. Let’s just do it ourselves.

There have been positive developments in Kassel as well. Members of the Jewish community and Ruangrupa had dinner together and are planning a football match. This is the best way to do this—to move away from the circus of the media and in the Bundestag, and to really meet the people whom this has affected.

Taring Padi’s work at Hallenbad Ost, one of the venues of Documenta 15. Photo: Ina Fassbender/AFP via Getty Images.

How was the dynamic with the larger community?

AS: There has been solidarity. People would come to us and tell us what was being said in the local and national newspapers or what was discussed on the radio because they know that we do not speak German.

There was a panel organized by Meron Mendel. Did you attend and what did you learn there?

HN: We learned a lot about the complexity of antisemitism in relation to antiracism, and a lot about the postcolonial discussion in the German context.

They spoke about blind spots in the decolonial discussion when it comes to Jewish topics.

AS: Yes, and it is true. There is a blank spot that requires cool-headed revisiting. How did the antisemitic views held by the Dutch when they colonized Indonesia affect people there? What kinds of comparison might be drawn between Nazi imagery of the Jews that they may have brought with them, and with how the Chinese were depicted in the 1910s and 1920s? We are actively researching and learning about this.

Let’s talk about the work itself that was removed by the board. How did these characters become a part of your work People’s Justice?

AS: We want to be able to answer that question, but we are not 100 percent sure who drew them, although there have been some speculations in the media. We work collectively on the floor with massive pieces of fabric. Some people draw outlines and then everyone chips in. At the time the work was made, in 2002, we had squatted in our art school building and were having punk gigs and hanging out there. Whoever showed up could help and contribute to the painting. Someone would maybe paint the figure and another would do the red coloring. Someone else would have added fangs, and so on. We think that more than one person painted them.

The military figure [of Mossad] is easier to understand. We wanted to visualize the involvement of the Western state apparatus in supporting the military dictatorship of Suharto.

We don’t do satire. We do want to dehumanize people who we identify as oppressors, so we turn them into other things, like animals or robots. When we curse in Indonesian we call people by animal names, so in a way we are cursing them.

The portrait of the Orthodox Jew with the sharp teeth and all those details exists with a group of other demon figures. Why is that there? What was in the minds of whoever painted that? What kind of collective consciousness brought that figure there? What do we understand about antisemitic imagery and the way that Nazis portrayed Jewish people in a derogatory manner? In the historical wayang puppet traditions of Indonesia, antagonistic figures are always dehumanized with these red eyes and fangs, and so that predates the way Nazis depicted Jews. How these different elements all combine is what we are trying to understand.

HN: We had displayed the work before, so in a way we knew about the characters. We did not know how strongly the reaction would be in Germany. When people make elements in the work, we do not want to erase them. We want to discuss them and the context. That is our way of working.

AS: Yes, we have never censored anyone working on our pieces, but we may have to revisit this policy. Maybe it is too naive to do things like that.

Art lovers look at the large painting People’s Justice (2002) by the Indonesian collective Taring Padi, covered with black cloth, on Friedrichsplatz. Photo by Uwe Zucchi/picture alliance via Getty Images.

So you knew the figures were there?

AS: Yes, we knew. We take ownership and responsibility. But we had seen it so many times over 21 years. It is like things in your living room—you stop really looking at them and considering them because you are so used to them. So, we never took them seriously or posited that those figures would have such a major impact in different contexts. We somehow did not see them when we displayed them in previous events, because we didn’t look for them.

None of that is an excuse. When we installed the work at Documenta, we were actually very worried about the red stars that are all over our work because of Russia’s war in Ukraine.

HN: Yes, we never had really worried about any character in our work, because it had not come up before. We were instead discussing the big narratives.

What will you do with the work now?

AS: We do not know yet exactly what to do with this work. Of course, we do not want to censor the work. We made a mistake, but we do not want to erase our mistakes. Mistakes should be there as a reminder for us but also as a starting point for discussions. If we destroy the work, we are just copying what Islamic fundamentalists did to our work, which was to burn it. But for sure, we will not show the work the same way again to the public.