Archaeology & History

The Hunt: Why Was the Neolithic Site Known as ‘Scotland’s Pompeii’ Abandoned?

The village was abruptly abandoned after roughly 600 years.

Beyond the north coast of Scotland lie the Orkney Islands, an archipelago of more than 70 islands scattered across the North Sea like breadcrumbs. Long winters, raking winds, and a treeless landscape make this an exposed and remote place to live. Four thousand years ago, however, the Orkneys were at the sophisticated center of Neolithic culture.

The islands are, in essence, one giant archaeological site, and those who so much as dig a a shovel into their fertile soil stand a decent chance of discovering burial tombs, standing monoliths, or stone arrangements. It wasn’t man, but rather an apocalyptic storm in 1850 that exposed the Orkneys’ most significant Neolithic site, Skara Brae, also known as the Scottish Pompeii.

The name is a corruption of an Old Norse expression meaning “hill by the reef,” suggesting the site had long been submerged in sand and lost to human memory. What archaeologists discovered through excavations begun in earnest during the 1920s was Europe’s best-preserved Neolithic village, consisting of eight rectangular structures connected by paved alleys that once housed up to 100 people. Here, geology has proved the archaeologist’s friend, with the Orkneys’ dearth of timber forcing the inhabitants to build in durable stone.

A view of one of the houses at Skara Brae, Orkney. Photo: Getty Images.

When Skara Brae was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1999, the organization called the village a “center of innovation and experimentation.” It was no hyperbole. Built from large flat stone slabs, the houses were insulated from the cold by an encircling mound of packed waste and a door that could be bolted shut. After visitors crawled inside, the first thing they saw was a dresser built into the back wall lined with the household’s most valuable possessions, such as grooved ware pots or ornate stone objects. The hearths, together with storage spaces, were dug into the floor and beds were arranged with men on the left and women on the right, a practice that continued on the islands into living memory.

The winning feature? Houses operated flushing toilets: holes connected to a communal drain that carried waste out to sea.

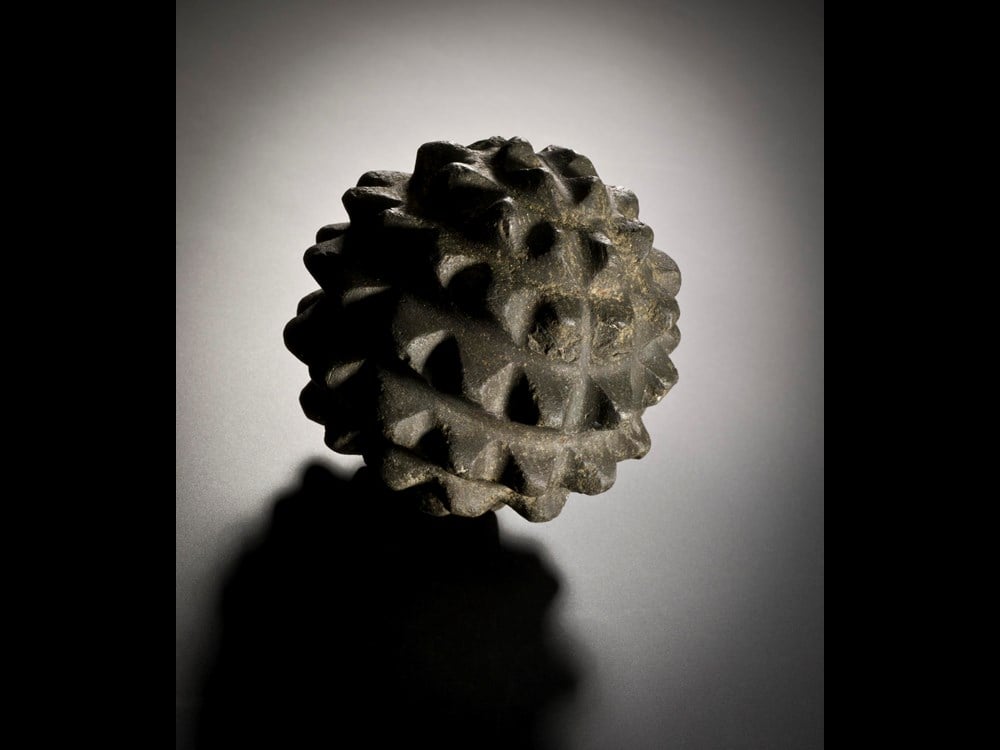

A carved stone ball of unknown use found at Skara Brae. Photo: courtesy National Museums Scotland.

A number of artifacts were also uncovered, and, when combined with the the intact architecture, they yield a rich picture of daily life. Milk and shellfish would have been presented in stone bowls, idols acknowledged in whalebone figurines, games played out with dice of walrus ivory, and beauty enhanced with jewelry made from the teeth of killer whales. They were sheep and cattle farmers who enjoyed a peaceful land of plenty, as evidenced by the lack of weaponry found at the site.

If elements of this Neolithic life echo those discovered in southern England and Ireland, it’s because they were first pioneered in Skara Brae. Inhabitation at Skara Brae began roughly around 3200 B.C.E.—prior to Egypt’s pyramids or India’s Harappan civilization—and its architecture of communal living was likely common to the islands. The area was along a North Sea route to Northern Europe, and this flow of prehistoric people saw the development of new ideas. Grooved-ware pottery was first made in Orkney, as were the aforementioned dressers. Its giant henges, Ring of Brodgar and Stones of Stenness, predate Stonehenge.

View of the interior of House one, through the door. Photo: Werner Forman/Universal Images Group/Getty Images.

And then around 2500 B.C.E., life at Skara Brae came to an end. In the archeological record, it can seem abrupt, as though people were forced to flee. This is unlikely—the sea, for one, was further from the village than it is today. More probable is that people gradually turned away from a communal living and towards one of isolated farmsteads that dot the islands. The root of this change remains unclear. Some point to the emergence of a ruling elite that forced a social restructuring, others to climate change that made the land less fertile.

Whatever the cause, one message of Skara Brae is clear: a society’s way of life can seem fundamental and permanent, until one day it isn’t.

The Hunt explores art and ancient relics that are—alas!—lost to time. From the Ark of the Covenant to Cleopatra’s tomb, these legendary treasures have long captured the imaginations of historians and archaeologists, even if they remain buried under layers of sand, stone, and history.