Archaeology & History

‘It’s the Start of Our Modern World’: How the British Museum’s Show of Ancient Artifacts Unravels the Secrets of Stonehenge

The British Museum makes a case for the sophistication of the mysterious people who built Stonehenge.

The British Museum makes a case for the sophistication of the mysterious people who built Stonehenge.

Sarah Cascone

Some 4,500 years ago, a prehistoric people built one of the world’s most enduring monuments, the monolithic sarsen slabs of Stonehenge, on what is now Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire, England. The mysteries of who built it, and why, have captured imaginations ever since.

The British Museum is hoping to elucidate this history in “The World of Stonehenge,” an extensive exhibition that opened this month to explore the society that built the famed stone circle, as well as their art, religion, and ways of life.

“Stonehenge is such a familiar monument, so people feel like they know it well in a sense—but actually, it’s quite shadowy. The people who built it and who lived in that world are not generally well understood,” Jennifer Wexler, a Bronze Age archaeologist who curated the show, told Artnet News. “What we really wanted to do in this exhibition is put Stonehenge within its context, and focus on objects that are connected to this broader world.”

While archaeologists still don’t know everything about this ancient place, there is one theory Wexler feels can be safely ruled out: “We know for sure that aliens didn’t build it, because we have archaeological remains of the people who did.”

Bronze Age Shropshire sun pendant (1000–800 BC). Photo ©the Trustees of the British Museum.

That includes stunning gold artifacts, some of them recent finds, like the 3,000-year-old Shropshire sun pendant, or bulla, discovered in a marsh by an anonymous metal detectorist in 2018. Possibly made by an Irish goldworker and featuring an embossed pattern that recalls the rays of the sun, the well-preserved piece of jewelry entered the British Museum collection in March 2020.

The exhibition also marks the debut of the 5,000-year-old Burton Agnes chalk drum, which the museum is touting as the nation’s most important prehistoric artwork discovered in a century.

Burton Agnes chalk drum, chalk ball, and bone pin (3005–2890 BC). Photo ©the Trustees of the British Museum.

“It was found buried with three small children and it’s a really, really stunning object,” Wexler said. “It has these kind of artistic motifs that you see in these tombs in Ireland, but also on houses in Orkney [an archipelago in northern Scotland], and on the top it has this cross shape, which we connect to a solar imagery. It encompasses almost the whole world at that time.”

But perhaps the most spectacular individual piece might be the famed Nebra Sky Disk, a bright blue bronze map of the night sky with a golden sun and a crescent moon made in northern Germany some 3,600 years ago (although there is some debate about the dating.)

Nebra Sky Disc, Germany (ca. 1600 BC). Photo courtesy of the State Office for Heritage Management and Archaeology Saxony-Anhalt, Juraj Lipták.

“The Nebra Sky Disk is a really fascinating object because it is essentially the first physical map of the cosmos, and it actually records a lot of the same observations that you can make at Stonehenge,” Wexler said.

In the beginning, Stonehenge was a cemetery. The first phase of the monument, begun 5,000 years ago, included only the inner circle of the smaller bluestone pillars. Those stones actually came from 175 miles away, in the Preseli Hill in Wales—where they may have been part of an earlier stone circle, according to a recent study.

The towering sarcens came some 500 years later, as the ancients’ use of the site continued to evolve. (Experts believe it took at least 1,000 people to move each slab 15 miles from the West Woods in Marlborough Downs, in a process that would have lasted generations.)

Stonehenge. Photo ©English Heritage.

Though the specifics of the laborious construction remain mysterious, recent technological breakthroughs are teaching archaeologists more and more about the ancient world that left behind this monument. This is helping unlock the mysteries of what life was like in Britain, Ireland, and northwestern Europe in the period surrounding Stonehenge’s construction—a time when these geographically disparate communities had cultural exchange across hundreds of miles.

“There’s been sort of a scientific revolution in archaeology,” Wexler said. “So we can tell the story of Stonehenge in a completely new and interesting way through some of the advances in archaeology, such as ancient DNA analysis and chemical analysis, or isotope analysis, which is connected to the water people drank when they were children, showing us where they’ve migrated.”

The exhibition tells the story of a society that was rapidly evolving as former hunter-gatherers embraced farming. This led to a greater interest in the passing of the seasons and movements of the heavens—which are reflected in the construction of Stonehenge, which aligns with the sun on the solstice.

Fine jadeite axe-heads made from material quarried in the high Italian Alps (4500–3500 BC). Photo ©the Trustees of the British Museum.

“It’s sort of the start of our modern world, because we still rely on farming,” Wexler said. “The sun ensures that your crops are going to grow and your animals are going to thrive, so it becomes a kind of core religious belief that is initially expressed through these monuments and solstice alignments with these stone circles. There is a very intentional kind of connection to the seasonal cycles, and people are kind of going to these places and celebrating at these times in a communal way.”

The show also includes a gorgeous array of jade axes made from stone from the Italian alps that would have been used to clear woodlands to create fields and meadows for grazing.

“The material is just so beautiful,” Wexler said. “The way they use the material, it really is artistic—some of these look like they could be modern sculptures.”

Although Stonehenge itself remains in situ on Salisbury Plain, the show does feature half of Seahenge, an ancient ring of wooden posts archaeologists discovered in a coastal marsh some 20 years ago, after a heavy storm. The other half of Seahenge is on view at the Lynn Museum in Kingsland, near where the ring was found, but this is the first time that the rest of it has ever gone on display.

Seahenge timber posts on display in the Lynn Museum. On long term loan to Norfolk Museums Service from the Le Strange Estate. Photo courtesy of the British Museum.

Though the northern European countryside would have been dotted with hundreds of such rings, finding an intact one, and not just the filled-in post holes, is incredibly rare.

Compared to Stonehenge, Seahenge “was probably more of a local shrine or the equivalent of a parish church for a local community,” Wexler said. “There was probably a mythology around it when they built it, a way of connecting the heavens and the underworld. Maybe through accessing the circle, you could get into the cosmos.”

Though the people of Stonehenge didn’t leave behind a written record, they were more sophisticated than history has given them credit for. They traveled long distances, had a sophisticated understanding of the movement of the sun and stars, and were becoming masters of the new technology of metalworking.

“These people are not primitive in any form,” Wexler said. “And they are making these incredibly complex objects with these mathematical calculations built into them and then translating them into really special objects. There’s a real ‘wow’ factor, because it’s surprising.”

See more artifacts from the exhibition below.

German Schifferstadt Golden Hat. Photo courtesy of the British Museum.

Decorated sun-disc from a woman’s belt (ca. 1400 BC), Langstrup, Frederiksborg Amt and Vellinge, Fyn, Denmark. Collection of the National Museum of Denmark. Photo by Roberto Fortuna and Kira Ursem, CC-BY-SA.

Dagger (with replica handle) from the Bush Barrow grave goods, (1950–1600 BC), Amesbury, Wiltshire, England. Photo by David Bukach, ©Wiltshire Museum, Devizes.

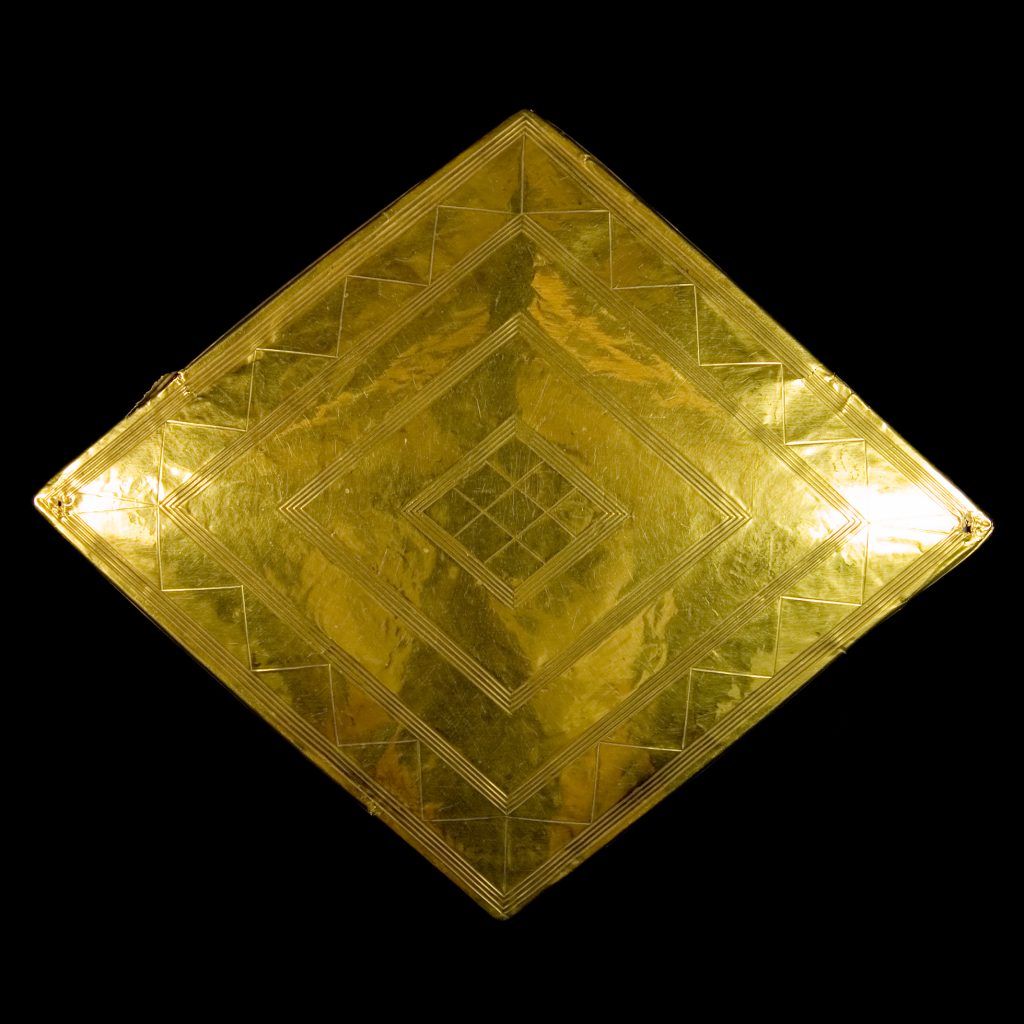

The gold lozenge of the Bush Barrow grave goods, (1950–1600 BC), Amesbury, Wiltshire, England. Photo by David Bukach, ©Wiltshire Museum, Devizes.

Lunula (2400–2000 BC), Blessington, County Wicklow, Republic of Ireland. Photo ©the Trustees of the British Museum.

The Mold Gold Cape (1900–1600 BC), Mold, Flintshire, Wales. Photo ©the Trustees of the British Museum.

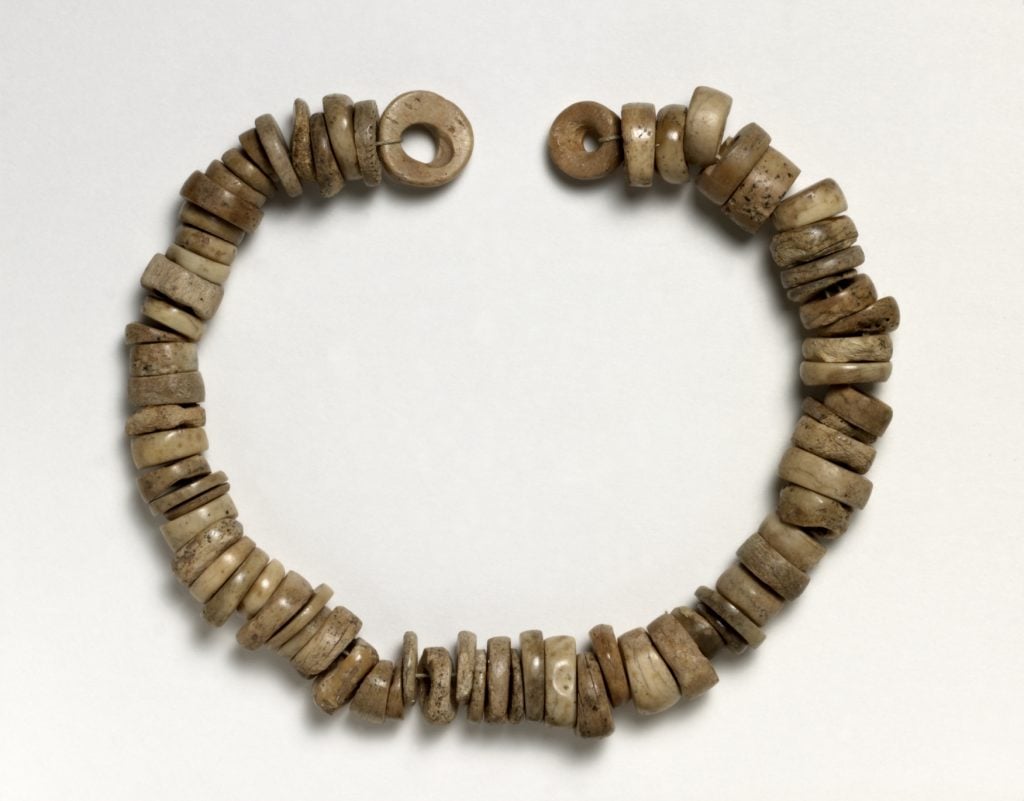

Bone-bead necklace (3100–2500 BC) part of the finds from Skara Brae, Orkney, Scotland. Photo ©the Trustees of the British Museum.

Fine jadeitite axe-heads made from material quarried in the high Italian Alps (4500–3500 BC). Photo ©the Trustees of the British Museum.

Gold flange twisted spiral torc (1400-1100 BC), Dover, UK. Photo ©the Trustees of the British Museum.

Bronze twin horse–snake hybrid (1200–1000 BC), from hoard Kallerup, Thy, Jutland, Denmark. Collection of the National Museum of Denmark/Ofret Museum. Photo by Søren Greve, CC-BY-SA.

“The World of Stonehenge” is on view at the British Museum, Great Russell Street, London, February 17–July 17, 2022.