Art World

3 Fateful Friendships That Empowered Revolutionary Artists to Change the Course of Art History

Discover the captivating stories behind a few of the art world’s most famous and enduring friendships.

Discover the captivating stories behind a few of the art world’s most famous and enduring friendships.

Maria Vogel

In the often-solitary life of an artist, it is rare to find a trustworthy peer to take on the role of confidante. And there’s a good reason why: critique, both internal and from others, is a never-ending obsession for an artist, whose livelihood is dependent on the personal outpouring of their craft. Indeed, it takes a very special sort of friendship between artists to persist through the highs and lows of their unique lifestyles and to overcome professional jealousy, easily bruised feelings, and, at times, differing opinions on what makes good art.

But the relationships between Yayoi Kusama and Donald Judd, Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Helen Frankenthaler and Grace Hartigan succeeded in doing exactly that, crossing divisions of gender, age, background, nationality, and circumstance to cement long-lasting bonds. In the name of lifting one another up as artists and as friends alike, these pairs provided each other with constant support that helped to realize artwork that ultimately shaped the course of art history. Here, we examine these three friendships more closely.

Yayoi Kusama, Flower Obsession (Sunflower), 2000. Courtesy of the artist.

Born on opposite ends of the earth just a year apart, Yayoi Kusama and Donald Judd’s paths would cross as young artists finding their footing in late 1950s New York City. While their initial meeting occurred after Judd wrote a rave review of Kusama’s first New York solo show for ARTnews, their relationship—mostly one of friendship but at times, romantic—would continue to deepen for decades to come. For a young artist coming up in the post-WWII New York art scene, the weight of a critic’s voice could not be understated, and in this arena, Judd provided Kusama with a strong foundation from which to launch her career. The two seemed to connect through their shared self-described label of “outsider” and over time, a through-line emerged in both artists’ practices that involved the outright rejection of any preexisting school of thought.

The 1960s would see Judd and Kusama enjoying a congruent rise of recognition. The mutual influence between the two was strengthened, too, by physical proximity after they moved into the same studio building in 1961. While there, both artists’ genre-defying work seemed to hit their respective strides, with Judd moving out of representational painting and into minimalism while Kusama continued to refine her practice.

Donald Judd in 1970. Photo Paul Katz, courtesy Judd-Hume Prize.

As their friendship progressed, mutual admiration for one another became a defining feature of Judd and Kusama’s relationship. Kusama once remarked that Judd was her first boyfriend, while Judd mentioned that Kusama’s work ethic and dedication to her practice was something he tried to model in his own life. Their common investigations of finding spirituality in repetition, concerns with spatiality, and stability from the pressures of the mind would pave the way for a new kind of dialogue in modern art. At times, each would rebuff the commercial art world and make work that many would deem too difficult to sell. And though their lives would geographically diverge when Kusama moved back to her native Japan in 1973, the two remained in close correspondence via letters of encouragement for a long time until Judd’s death in 1994.

Arnold Newman, Helen Frankenthaler, Provincetown (1963).

Photo: The Estate of Arnold Newman, courtesy of Howard Greenberg Gallery.

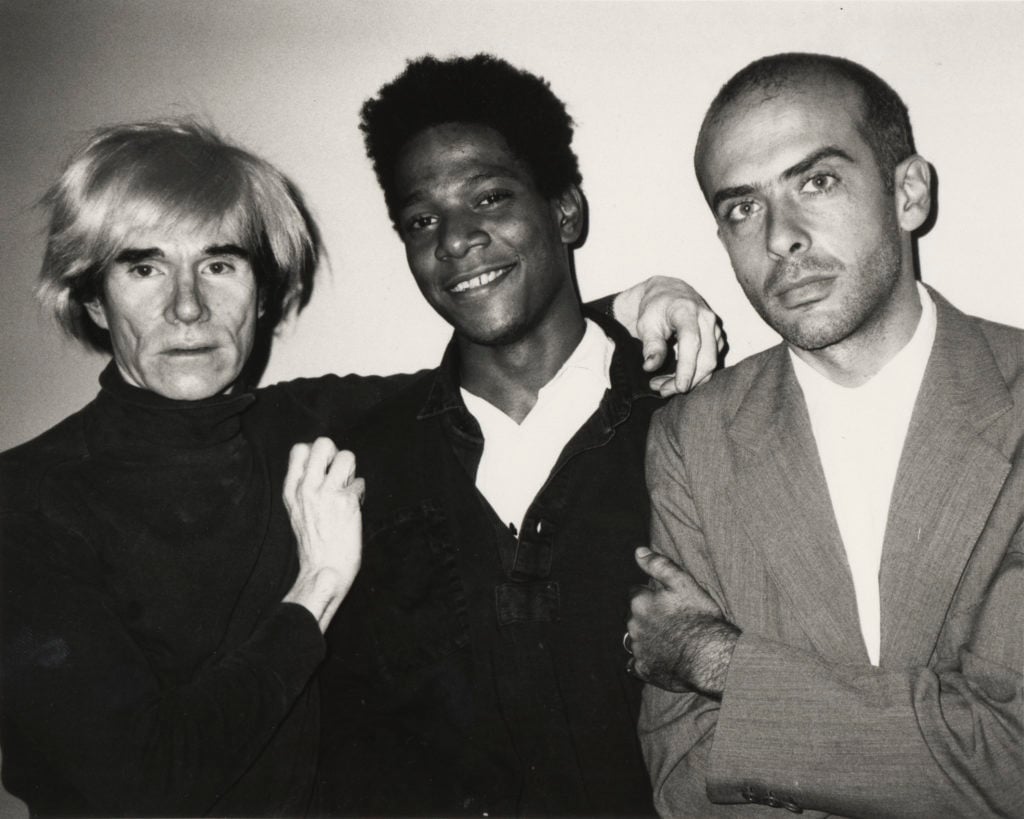

For a fleeting moment in the late 1950s, female painters working in the United States became a focal point of critical attention, ushered into the mainstream art world through their glamorization in a 1957 LIFE magazine feature. Though this moment would come to pass, and widespread attention once again returned largely to male artists, Helen Frankenthaler and Grace Hartigan, two standouts of this period, persisted in carving out space for women in the art world while maintaining a close bond.

Frankenthaler and Hartigan shocked the scene with painting styles that were considered too masculine for their makers. Monumental in scale and full of energy and action, both artists embraced practices that would knowingly push the canon of painting. They met through their shared social circle of New York’s downtown artistic community, and though the two were in close kinship with many of their male counterparts who were enjoying worldwide recognition—such as Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning—Frankenthaler and Hartigan’s inclusions in the contemporary art conversation of the time were few and far between.

A young Grace Hartigan painting in her studio in the 1940s at the beginning of her artistic career. Image courtesy Syracuse University.

Despite their hardships, both continued to make their mark in a man’s world that tried to claim singular ownership of abstract painting, and their continued support of one another would prove crucial in the ongoing fight for recognition of women artists the world over.

In later years, after enjoying distinct milestones of success, such as Frankenthaler’s representation of the United States in the 1966 Venice Biennale, and Hartigan’s inclusion as the only woman in MoMA’s 1956 show “Twelve Americans,” both artists sought to defy the conventions of abstraction by painting scenes from life with recognizable imagery. Moving beyond the genre of abstract expressionism, they incorporated written source material such as poetry, fiction, and memoir into their paintings. Together, they would reject stylistic decisions they knew had become widely popular, opting instead to push their work into new territory.

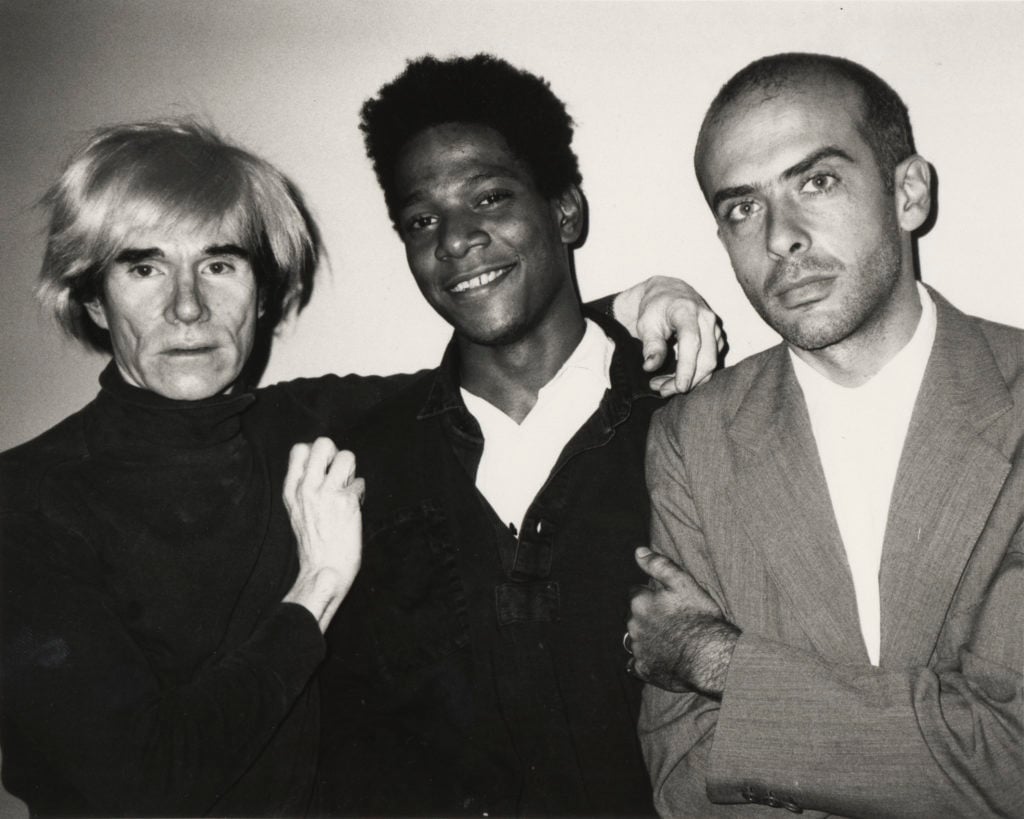

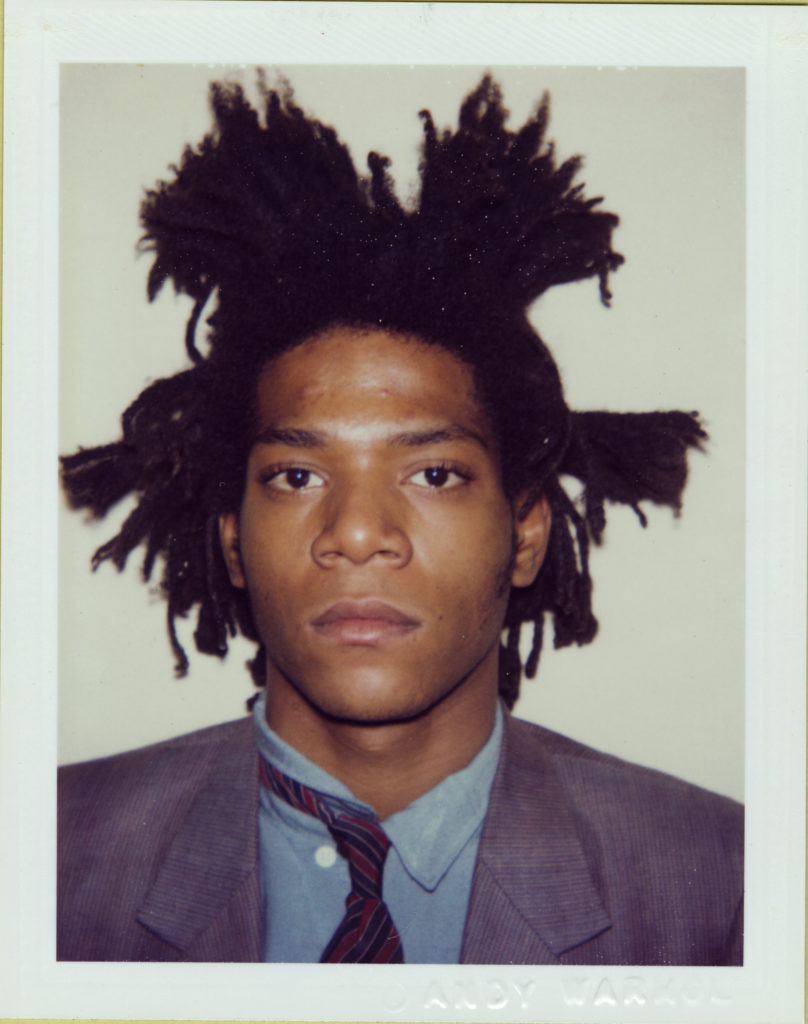

Andy Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat (1982). The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; © 2018 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

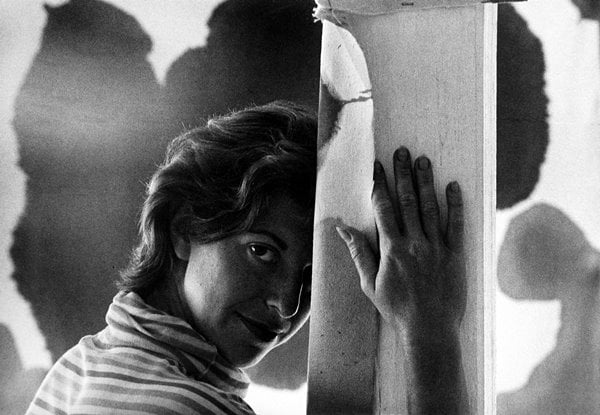

To try and fit Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat’s dynamic relationship into any one category is an impossible feat. When the two formally connected over lunch at the suggestion of a mutual friend, they began an association that would blur the distinctions between mentor/mentee, father/son, and artist/muse, forming a bond that today receives household recognition even beyond the art world.

By the time their two worlds convened in 1982, Warhol was an established global figure whose career had seen overwhelming success. Basquiat, at 32 years Warhol’s junior, had just begun to make a name for himself in New York as a graffiti artist. In this kismet moment, the two recognized the potential that a partnership would award their vastly different practices and lives. Whereas Basquiat had long looked up to Warhol, seeking similar fame and recognition, Warhol was inspired by Basquiat to seek out new ways to innovate in the later stage of his career. A mutually beneficial collaboration began between the two, who would remain virtually inseparable until Warhol’s death just six years later.

Andy Warhol in front of several paintings in his “Endangered Species” series at his studio, the Factory, in Union Square, New York, New York, April 12, 1983. (Photo by Brownie Harris/Corbis via Getty Images)

Each seemed to bask in an aura of intrigue while in the presence of one another, as if attracted to the polarity of the other’s persona. Their relationship ignored convention, painting them as an odd couple in what was at times incredibly personal and intimate, though not outright romantic. Artistically, Warhol’s refined, machine-like style was challenged by the stark rawness which imbued all of Basquiat’s work. Their opposing philosophies seeped into each other’s output throughout the course of their friendship, resulting in a period of revitalized work for both that would come to define their careers.

At times turbulent, the bond between Warhol and Basquiat endured until Warhol’s unexpected death in 1987. The loss of Warhol left a massive void in Basquiat’s life, spurring the start of especially destructive behavior that would ultimately claim his life just one year later. And though both artists’ lives were tragically cut short, their influences on the art world today continue to be as prevalent as ever before.