Art & Exhibitions

See Our Top 20 Exhibitions in Europe in 2016

From Bosch and Botticelli to Donna Huanca and Omer Fast, see what stuck with us this year.

From Bosch and Botticelli to Donna Huanca and Omer Fast, see what stuck with us this year.

Lorena Muñoz-Alonso &

Hili Perlson

In a rather quiet year in terms of major European art events—besides Manifesta 11 and the Ninth Berlin Biennale—it was down to museums, galleries, and nonprofits to deliver the thrills European art lovers long for.

It was a particularly rewarding year for lovers of painting, who were able to enjoy a plethora of exhibitions by the most revered Old Master and modern painters, from Caravaggio to James Ensor. Here’s our top 20 shows from museums across Europe this year, in chronological order:

Goshka Macuga, To the Son of Man Who Ate the Scroll, 2016. Photo: Delfino Sisto Legnani Studio. Courtesy Fondazione Prada

Goshka Macuga, “To the Son of Man Who Ate the Scroll” at Fondazione Prada, Milan, February 4 – June 19.

The London-based Polish artist Goshka Macuga slips between descriptors like curator, researcher, and freewheeling dramaturge to create masterful installations using pieces by other artists and loaned artifacts in fascinating nets of cross-references. While her practice often draws from the past, and has centered on memory and mnemonic techniques in recent years, this ambitious exhibition spread over three gallery spaces at the still-crisp Fondazione Prada in Milan imagined a post-human future.

The first work encountered by viewers was the eerie android Macuga designed in collaboration with A-Lab, Japan. Reciting a speech amalgamated from philosophical texts and rhetoric traditions—with some references to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein thrown in the mix—the soft-spoken golem sat amid works by Phyllida Barlow, Robert Breer, James Lee Byars, Ettore Colla, Thomas Heatherwick, Eliseo Mattiacci, and Macuga, relaying his wisdom in an endless loop. At one point, the bearded humanoid “wondered” who he might have been programmed to preserve all this knowledge for.

Contemplations on a post-human future seem even timelier from the perspective of the end of a turbulent year, with a frightening prospect for the one to come.

Julian Rosefeldt, Manifesto (2015), film stills featuring Cate Blanchett. Courtesy Julian Rosefeldt and VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

Julian Rosefeldt, “Manifesto” at Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin, February 10 – November 6

One of the most talked-about events of the art year in Berlin, “Manifesto” is now on view at the Park Avenue Armory in New York through January 8, 2017. The NY stint is rather short compared to the 10-month duration of the screening of this video work in Berlin, extended due to popular demand.

The popularity is hardly surprising considering that this 13-channel work features a chameleon-like Cate Blanchett appearing in 13 different roles, performing a stellar delivery of a journey through the history of art, thought, and political convictions with texts culled from dozens of manifestos. At a talk with the artist in Berlin, Rosefeldt confided that the sequences were shot in less than two weeks, praising Blanchett’s outstanding talent.

Filled with vitality, anger, and a sense of urgency, these texts were composed by the likes of Tristan Tzara, Kazimir Malevich, André Breton, Claes Oldenburg, Yvonne Reiner, Sturtevant, Adrian Piper, Sol LeWitt, or Jim Jarmusch, to name a few, and their energy is intensified by Blanchett’s altering roles, which position these ideas in the here and now and offer a thought-provoking and inspiring respite from the barrage of character-limited angry messages we’ve become accustomed to otherwise on social media. At one point, the 13 short clips become synchronized, and one common mantra, like a call to arms, resonates throughout.

Installation view of “Jheronimus Bosch – Visions of Genius” at the Noordbrabants Museum. Photo Marc Bolsius, courtesy Noordbrabants Museum.

Hieronymus Bosch, “Visions of Genius” at Noordbrabants Museum, s-Hertogenbosch, February 13 – May 8; and “The 5th Centenary Exhibition” at Museo del Prado, Madrid, May 31 – September 9

The landmark exhibition devoted to Hieronymus Bosch marked the 5th centenary of this death. The show toured between the Noordbrabants Museum, in the native town of the painter in The Netherlands, and Madrid’s Museo del Prado, which owns some of the great masterpieces of the artist, including the triptychs of The Garden of Earthly Delights, The Adoration of the Magi, and The Haywain.

The collaboration, however, was fraught with disagreements over the authentication of two paintings that the Prado has in its collection, which resulted in the Madrid museum refusing to loan the works in question. Kerfuffles aside, both shows were astonishing, affording a headfirst plunge into the oneiric, endlessly imaginative, and terrifying yet hilarious universe of Bosch, who was able to render like nobody else the surreal aspect of religious imaginery. Seeing so many Bosch works together was a once-in-a-lifetime experience, enjoyed by a combined total of over 1 million visitors.

Installation view of “Hilma Af Klint: Painting the Unseen” at the Serpentine Gallery. Courtesy Serpentine Gallery.

Hilma af Klint, “Painting the Unseen” at the Serpentine Gallery, London, March 3 – May 15

Although it was actually the Camden Arts Center which brought the first exhibition of Hilma af Klint to the London public, back in 2006, “Painting the Unseen” showcased some key series that had never been exhibited in the UK until now. Co-curated by Daniel Birnbaum, director of Stockholm’s Moderna Museet—which staged a major and widely-praised retrospective of the Swedish artist in 2013—the exhibition shone a new light on the phenomenal Swedish painter, who can be credited with experimenting with abstraction before her (male) contemporaries Wassily Kandinsky, Kazimir Malevich, and Piet Mondrian.

Af Klint was a relatively successful artist in her lifetime, making a modest living as a painter of traditional landscapes, botanical drawings, and portraits. Yet, underneath that conventional surface lurked a much more transgressive approach to art. Influenced by the mystic and occultist beliefs of Theosophy, she joined four other female artists and formed a group called The Five, conducting séances in which spirits supposedly communicated with them via images. Af Klint translated these visions into dazzling series, in which figuration meets with geometrical abstraction in paintings that are not only beautiful and hypnotizing, but also some of the strongest explorations of the collision of the natural and spiritual worlds.

Sandro Botticelli, The Birth of Venus (c.1486). Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

“Botticelli Reimagined” at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, March 5 – July 3.

This charming exhibition first opened in Berlin’s Gemäldegalerie in late 2015 under the title “The Botticelli Renaissance,” before touring to London’s V&A. The difference in the titles give clues to the focus of each iteration: while both institutions worked together displaying the same exponents, the Berlin museum highlighted the ways in which Sandro Botticelli’s work captured the imagination of the Pre-Raphaelites, who practically rediscovered the forgotten Florentine painter in the 19th century.

Having ushered in a veritable Botticelli revival, there was no stopping the extent to which his work—though rather small in scope—would leave its mark on artists throughout the 20th century, with his Birth of Venus becoming one of the most appropriated artworks in popular culture.

The Botticelli show at the V&A—the largest in the UK since 1930—further explored Venus’s impact on visual culture, from art to fashion, design, and film. Works by Orlan, David La Chapelle, Yin Xin, and many more provided powerful proof of the lasting impression this idealized scene has left on the collective imagination. What’s more, the variety of ways in which Venus has been quoted, commented on, and reimagined in contemporary art ended up tracing a gripping short history of issues like gender wars and identity politics.

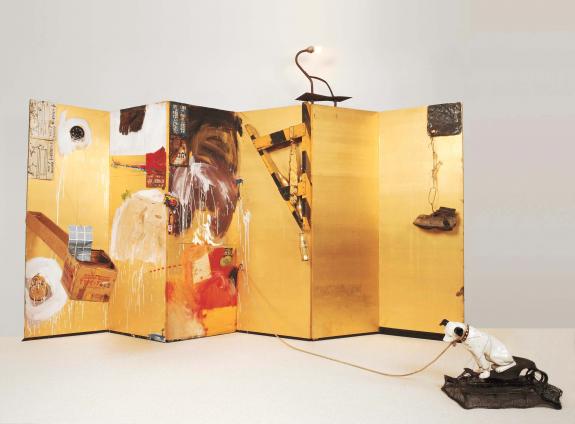

Francis Picabia, Têtes superposées (1938). ©2016 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

Francis Picabia, “Our Heads Are Round so Our Thoughts Can Change Direction” at Kunsthaus Zurich, June 3 – September 25

Before this spectacular retrospective toured to the Museum of Modern Art in New York, it premiered at Kunsthaus Zurich, decidedly stealing the show for many art world professionals who were in the Swiss city for Manifesta 11.

Coinciding with the city’s celebrations of the centenary of Dada, the museum focused on the movement’s most slippery individualist. The staggering 200 artworks in the show, ranging from collaged postcards to paintings, drawings, film, and even textiles are rendered in a dizzying and confusing array of styles, which have led in the past to a reading of this artist as an irreverent prankster.

Indeed, Picabia’s legacy is elusive; although his contributions to major European art movements of the 20th century are recognized, his later paintings of pin-up beauties were long written off as kitsch and detested by his contemporaries.

But displaying his rich output in one retrospective, the show achieves precisely what retrospection aims at: a new understanding crystalized through the distance of time. Art mustn’t be bound to restrictive dictations of taste; high and low must co-exist if we ever want to find a way out of the echo chamber.

Installation view of Marko Lulić’s Death of The Monument (2009) at the “Par tibi roma nihil” exhibition. Courtesy Noms Foundation.

“Par tibi roma nihil” at the Roman Forum & Palatine Hill, Rome, June 24 – October 23

Talk about a monumental setting… Organized by Nomas Foundation, “Par tibi roma nihil” gathered works by 33 acclaimed international artists—including Daniel Buren, Rosalind Nashashibi, Jannis Kounellis, David Horvitz, and Tris Vonna-Michell—and displayed them in the historical Palatine ruins in Rome, most of them outdoors or in ruined nooks.

You’d think that such an impressive backdrop could have easily dwarfed the works, but the curation of the show—courtesy of the archeologist and contemporary art collector Raffaella Frascarelli—was so exquisite that it managed to create a compelling visual, and sometimes conceptual, continuum between the historical and the modern. The witty sculptural intervention of Kader Attia, the delicate museological display of Isabelle Cornaro, and Michael Dean’s small sculptures sitting atop ruined Roman columns afforded some of the most sublime moments of an extremely ambitious—and successful—show that left a group of visiting international art journalists speechless.

Zvi Goldstein, left: Reconstructed Memories (Lariam B), (2001 – 2005), right: Cactus Model, (1991). Photo courtesy of Stedelijk Museum voor Actuele Kunst, Gent and Daniel Marzona, Berlin.

Zvi Goldstein, “Distance and Differences” at the S.M.A.K, Ghent June 24 – October 23

This important exhibition surveying the life’s work of the truly radical artist Zvi Goldstein, is not only a long overdue look at his unique position in art history, it is also essentially what saved the artist’s oeuvre from eradication. “I was going to send it all to be destroyed,” Goldstein told artnet News at the opening. “I couldn’t keep it in storage anymore.”

Having studied in Italy and initially winning some recognition (and working as an assistant to Sol LeWitt), by 1978 Goldstein experiences a deep crisis of faith in art, induced by the Post-Modernist discourses of the time.

Believing that Western visual culture has exhausted its means of representation, he decides to focus on the visual and contextual traditions of the so-called peripheries. Years of travels follow; solitary research trips to monastic communities and tribal societies all across Africa, Asia, and Asia Minor.

The resulting works form alluring compositions that invoke both the familiar and the unknown. Every single detail is specially produced, using industrial technologies that were extremely advanced for the time. (One could think of contemporary sculptors such as Magali Reus or Helen Marten as his followers, though it is probable they’re not familiar with his work). Goldstein rejects the tropes that equate non-Western art traditions with hand-made, exotic, and gestural artifacts and replaces them instead with monumental apparitions that hark back to pre-Modern traditions.

Firmly positioned within the “peripheral avant-garde,” the work’s most challenging aspect is its negation of expectations: Goldstein proposes inclusion rather than deconstruction, and fluid hybridity rather than a discourse on Western dominance.

Installation shot of “Francis Bacon: Monaco and French Culture” at the Grimaldi Forum, Monaco. Courtesy Grimaldi Forum.

“Francis Bacon, Monaco and the French Culture” at Grimaldi Center, Monaco, July 2 – September 4

One of the summer’s blockbusters—which later traveled to the Guggenheim Bilbao—was this survey of Francis Bacon’s work, with a focus on his relationship with French cultural in general and with Monaco in particular. The show was carefully curated by Bacon expert Martin Harrison, fresh from having published the painter’s catalogue raisonné, a scholarly tour de force that allowed him to trace (and exhibit) a number of rarely seen works, including a series of portraits with brightly-colored backgrounds, his tortured figures softened by light pinks and greens.

The show also benefited from its dramatic exhibition design (also by Harrison) inspired the Swiss architect and stage lighting theorist Adolphe Appia, featuring tall, heavy curtains and metallic bars in the shape of beams and doors that replicated the domestic cages Bacon painted to frame figures. The show included works by artists that were key in the development of Bacon’s pictorial universe, like Pablo Picasso, Alberto Giacometti, Fernand Léger, Chaïm Soutine, and Auguste Rodin.

Installation view of “Systematically Open?” Collier Schorr – Anne Collier at Luma Arles. Courtesy LUMA Foundation. Photo Lionel Roux

“Systematically Open?” at Luma Arles, July 4 – October 24

Slated to inaugurate its flashy Frank Gehry tower next year, Maja Hoffmann’s Luma Foundation in Arles opened the exhibition campus around it this past July, designed by Selldorf Architects. The first show at the site, which includes studios and exhibition spaces housed in the re-purposed railway workshops, was a thoughtful, smart, and beautifully designed critical rethinking of the production, presentation, and structural limitations of the photographic medium.

Four artists—Walead Beshty, Elad Lassry, Zanele Muholi, and Collier Schorr—each developed a curatorial project together with architect Philippe Rahm, whose contribution as the show’s designer was outstanding. Beshty for example devised a section that centered on modes of production and distribution, with works by Hito Steyerl, Kelley Walker, and Boris Mikhailov, among many others, in a meandering landscape rendered in bright colors.

Collier Schorr curated a dialogue between her work and that of Anne Collier, perhaps a retort to their being easily confused. The strength of this large-scale exhibition was in its deep awareness to historical displays of photography, ranging from El Lissitzky’s photography-based installations of the late 1920s, to Edward Steichen’s seminal and encyclopaedic The Family of Man. A timely and important show indeed, this reassessment of artistic image production in the age of social media should be restaged in other locations, too.

Jean-Michel Pancin, In Memoriam (2016) at Reading Prison’s chapel, featuring the original wooden door of Oscar Wilde’s cell. Photo Lorena Muñoz-Alonso.

“Inside – Artists and Writers in Reading Prison” at Reading Prison, September 4 – December 4.

In September, with the summer coming to an end and the post-holidays blues looming large in the horizon, UK-based art lovers had at least this very promising show to look forward to. Staged in the cells and corridors of the infamous Reading Prison, and featuring a top group of artists and writers—including Wolfgang Tillmans, Steve McQueen, Patti Smith, Rober Gober, Nan Goldin, and Felix Gonzalez Torres—”Inside” focused on themes of incarceration, deprivation of freedom, and separation, taking the figure of Oscar Wilde as a starting point. Wilde was Reading Prison’s most famous inmate, where he was incarcerated in 1895, charged with “acts of gross indecency with other male persons,” after losing a legal battle with the father of his young lover Lord Alfred Douglas (Bosie).

There were many ways in which this exhibition could have gone wrong (exploiting the very real suffering of minorities and convicts for art’s sake, or the setting making the works too literal, for example), but “Inside” managed to triumph, finding a rare balance between art and spectacle. The works felt strangely at home in the cells, respectful yet inspiring, even uplifting. The heavy, somber atmosphere of the prison, which stuck to viewers’ consciousness for hours afterwards, became the perfect backdrop for a splendidly curated show that was, for this writer, a unique art experience, and probably the best show of the entire year.

Installation view of “Streams of Warm Impermanence” at DRAF, 2016. Photo Tim Bowditch, courtesy DRAF.

“Streams of Warm Impermanence” at DRAF, London, September 16 – December 10

DRAF—which organizes one of the best parties of Frieze Week featuring a great line up of performances—had a phenomenal group show on view during London’s top art week. “Streams of Warm Impermanence” explored issues to do with the body and corporeality from the point of view of our networked times. The most interesting aspect was the juxtaposition of young artists, like Justin Fitzpatrick, Ann Hirsch, Donna Huanca, and Athena Papadopoulos with works by seminal figures like Renate Bertlmann, Carolee Schneemann, David Wojnarowicz, and Martin Wong.

This visual dialogue shone a light on the synchronicities and ongoing concerns that artists from different generations share, but it also highlighted how different historical periods create specific approaches and strategies as a result of evolving techniques and technologies. A feast for the eyes of lovers of fleshy sculpture and wacky figurative painting.

Performance view of Donna Huanca’s “Scar Cymbals” at 176. Photo Thierry Bal, courtesy 176.

“Donna Huanca: Scar Cymbals” at Zabludowicz Collection, London, September 29 – December 18

Nearby, at another private collector-led institution, the Zabludowicz Collection, Donna Huanca, also showing at DRAF, got her first solo show in London, and boy, did it cause a stir. The presence of naked bodies performing on plynths and plexiglass cages made some viewers uncomfortable, but no one could stop looking at the hypnotizing performance regardless, soundtracked by some of the models themselves, operating electronic musical gadgets.

“Scar Cymbals” became one of the most talked about exhibitions during Frieze Week, no mean feat considering it had a lot of competition. The show had everything: nude performance, droning sound art, intriguing paintings, beguiling sculpture … In fact, it seems that for Huanca there’s actually no distinction between types of media or support: bodies become canvases and sculptures become stage characters in one dazzling continuum. Yes, it could be said that her work objectifies the human body in the sheer sense of the word, but the use of both female and male models, and the fact that this is work made by a female artist, made it compelling, empowering, and refreshing.

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, The Taking of Christ (1602). On indefinite loan to the National Gallery of Ireland from the Jesuit Community, Leeson St., Dublin who acknowledge the kind generosity of the late Dr Marie Lea-Wilson. Photo ©The National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin.

“Beyond Caravaggio” at the National Gallery, London, October 12, 2016 – January 15, 2017

For an Old Master painter, Caravaggio was a rather modern artist, in the “bohemian” sense of the word. Transgressive and louche, the murky details of his personal life—he killed a young man during a brawl—far for dampening his tremendous talent and oeuvre, render him even more fascinating (hardly surprising, then, that the British filmmaker and artist Derek Jarman devoted one of his best feature films to him).

For those seeking a monographic exhibition, “Beyond Caravaggio” might have been disappointing for, although it does showcase a number of masterpieces by the Italian legend (six), it mainly features works (43 in total) by his growing circle of imitators, those who created under his shadow, some with more originality than others. Still, the show is a fascinating exploration of artistic influence, of how artistic innovations and styles spread and conquer as if by contagion. And you get to see Caravaggio’s The Supper at Emmaus (1601) and Taking of Christ (1602), which confirm, unquestionably, that no successor could ever reach the heights of the master.

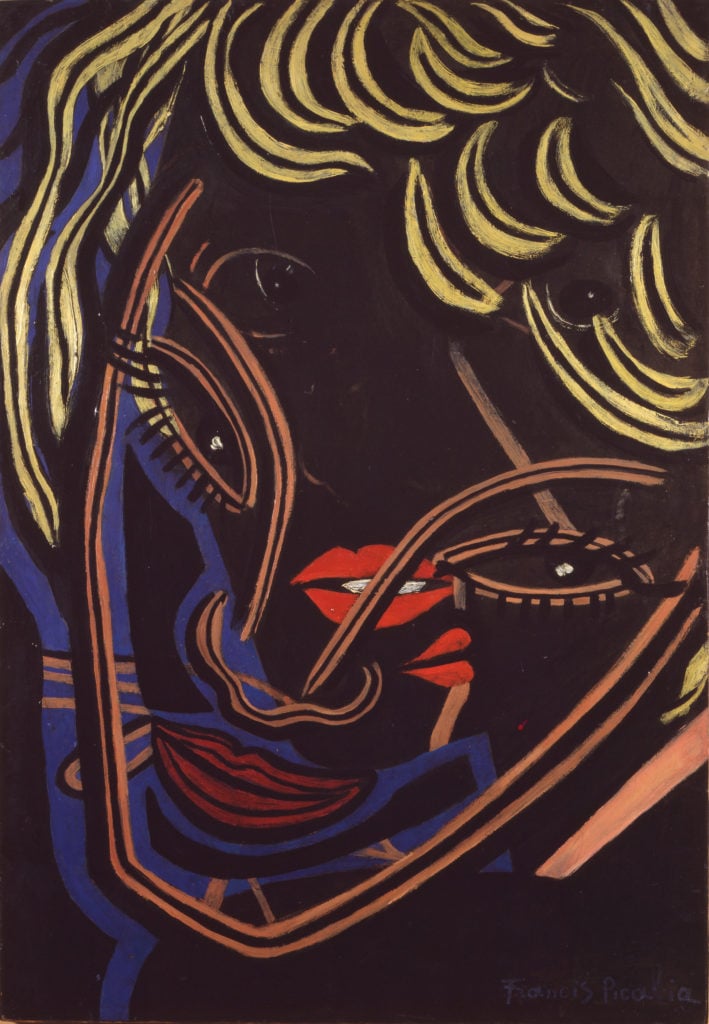

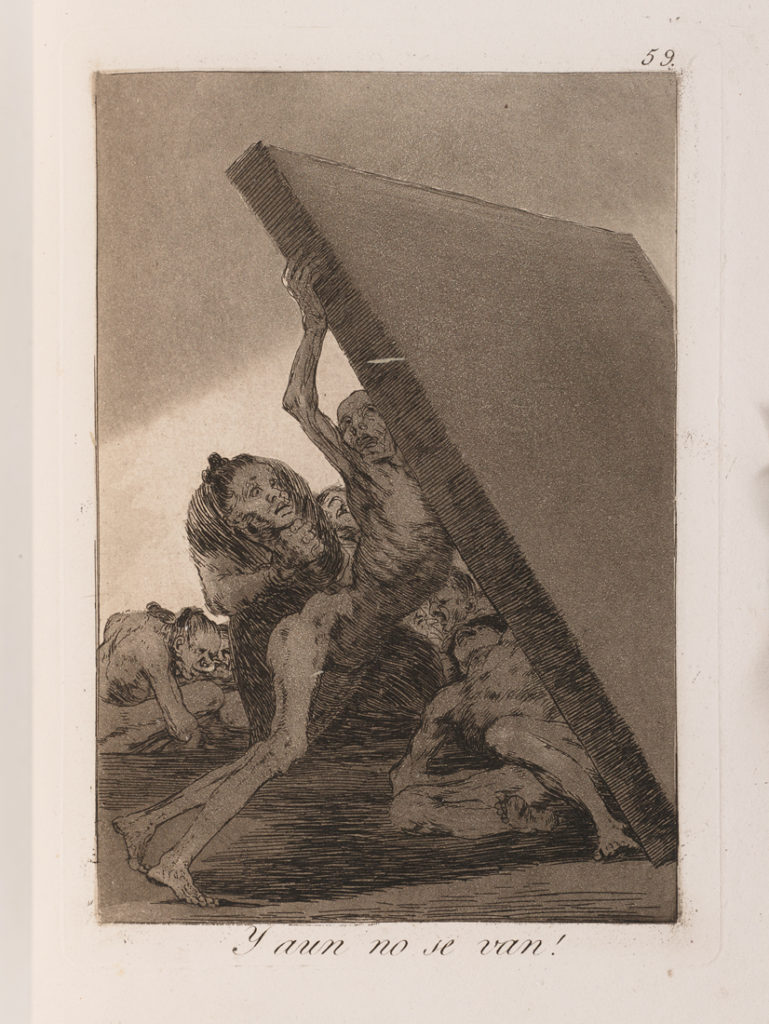

Francisco de Goya Los Caprichos (1799), Collection Sylvie and Georges Helft. Photo Jean de Calan.

“Soulèvements (Uprisings)” at the Jeu de Paume, Paris, October 18, 2016 – January 15, 2017

If you came to Paris especially for FIAC this year, it was easy to see your schedule quickly fill up with other, more hyped shows, like Tino Sehgal at Palais de Tokyo, Maurizio Cattelan at the Monnaie de Paris, or the marvellous Shchukin Collection at Fondation Louis Vuitton (see our next entry). But “Soulèvements,” curated by French philosopher and art historian Georges Didi-Huberman, was the one show on view that week that managed to uplift amid a year of constant bad news. And it did so not with eye-popping design or trendy names but with its sheer intellectual rigor—and a serious insistence on fun.

In a year that saw Michael Gove, UK’s former secretary of education, come out with the populist claim that we don’t need experts during his pro-Brexit public appearances, Didi-Huberman’s expertly devised journey through moments, visual and gestural, of upward movements—insurrections and uprisings but also rising from the ashes or simply looking up—made the synapses in the brain tickle with excitement.

The plethora of works on view—some anonymous cartoons, some seminal works by important artists—could speak of man’s endless struggle with oppressive forces and history repeating. Yet, Didi-Huberman’s message asserts that as long as we still have the power to imagine, there will always be ways to rise up in difficult times.

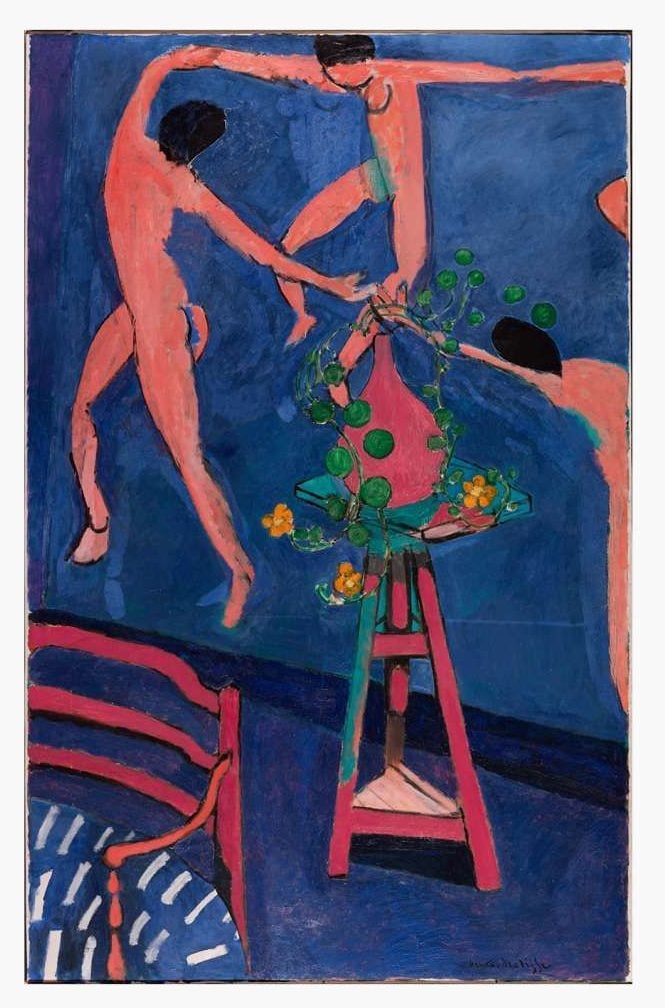

Henri Matisse, Nasturtiums and “La Danse” II (1912). The Pushkin state Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow, ©Succession H. Matisse, Photo ©The Pushkin state Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow.

“Icons of Modern Art. The Shchukin Collection” at the Fondation Louis Vuitton, October 22, 2016 – February 20, 2017

Critics were grasping for superlatives when the spectacular collection of modernist masterpieces, once owned by Russian textile magnate Sergei Shchukin, was reunited for the first time since the Russian Revolution for an outing at the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris, a first outside of Russia.

Though the works on view are only a sampling, the show is astonishing not only for the daring acquisitions of the adventurous collector, an early patron and close friend of Henri Matisse (Shchukin commissioned The Dance (1909-10), and Music (1910), two of the artist’s most celebrated works), but also for the diplomatic feat of having managed to negotiate the loans (Russia doesn’t loan any works to American museums, for example).

However, despite Bernard Arnault’s best efforts, the mega collector and CEO of LVMH could not bring Putin to attend the opening as planned, following a comment from François Hollande. (He did pen a text for the show’s catalogue, though).

Diplomacy aside, there’s no other way to describe this exhibition other than as a once-in-a-lifetime event. Shchukin collected in depth, and followed artist’s careers rigorously. He amassed 50 Picassos, 13 Monets, eight Cezannes, four Van Goghs, and 38 works by Matisse. He even dedicated an entire room of his Moscow mansion to his 16 Gauguin Tahiti paintings.

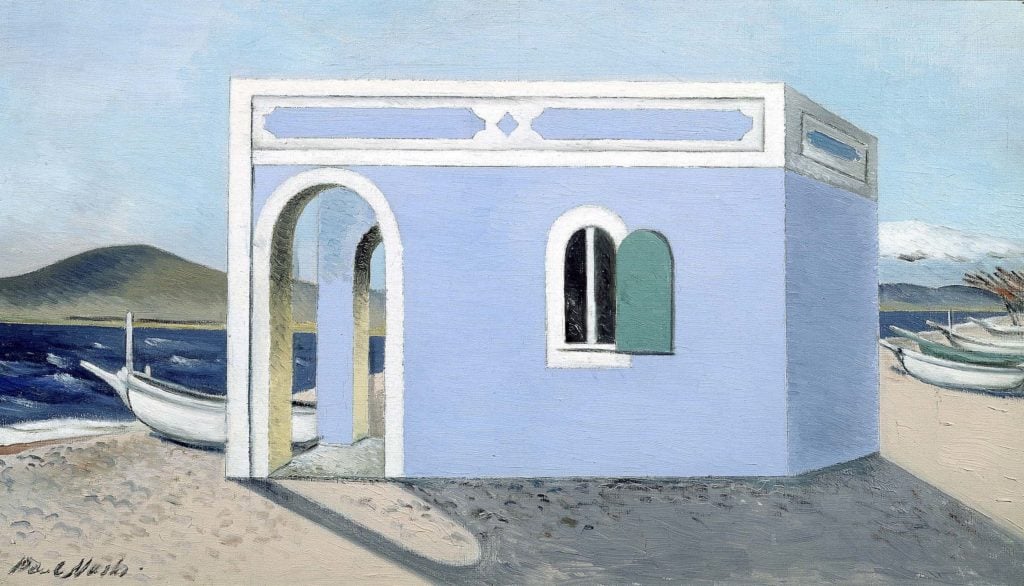

Paul Nash, Blue House on the Shore (1930-1). Photo ©Tate.

Paul Nash at Tate Britain, London, October 26, 2016 – March 5, 2017

Paul Nash was an astonishing Modern British painter. For some, he is best-known as a war artist, for the beautifully desolate and dystopian landscapes he painted as result of his traumatic experience in the trenches of the World War I, and then as an official war painter during World War II. For others, he was the foremost figure of British Surrealism, alongside the historian and writer Roland Penrose. Nash was both, but he was also much more, something this fantastic retrospective at Tate Britain makes abundantly clear.

From his early drawings inspired by William Blake, the Pre-Raphaelites, German Romanticism, and French Symbolism, to the Giorgio de Chirico-inspired metaphysical landscapes he painted in the 1930s, this exhibition is full of surprises that are testimony to Nash’s towering presence in the art made in Britain in the first half of the 20th century.

There’s also of course a very generous selection of his war landscapes, like The Menin Road (1919) and the almost abstract Battle of Germany (1944), and of his surrealist compositions, including Landscape for a Dream (1936-38) and Equivalent for Megaliths (1935). For the art history nerds, moreover, there’s also a wealth of amazing archival material in the room dedicated to his Swanage period, in the height of his affair with the artist Eileen Agar. This show would also win the prize for the best color-painted walls in a painting exhibition, if there was one. Never did a white cube seem more pointless.

James Ensor, The Intrigue, 1890 Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten,

Antwerp. Photo ©Royal Museum for Fine Arts Antwerp / www.lukasweb.be – Art in Flanders vzw. Photo Hugo Maertens/©DACS 2015.

“Intrigue: James Ensor by Luc Tuymans” at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, October 29, 2016 – January 29, 2017

The market of the Belgian painter James Ensor is definitely having a moment, but it feels good to speak about this immensely talented yet (until now, at least) rather overlooked artist in parameters that do not pertain to numbers. Let’s thank fellow Belgian painter Luc Tuymans for this, and for his timely curated exhibition that shows us the art of Ensor in all its irreverent splendor and topical social satire. The show is certainly small, yet it manages to pack most of Ensor’s best pieces in, including the titular The Intrigue, as well as some rarely seen drawings and etchings.

It also features a handful of artworks by other coeval and contemporary artists, including paintings by Léon Spilliaert, Jean-Luc Pourbaix, Karl Kesten, and Tuymans himself, thus establishing a lineage between Ensor’s eccentric carnival scenes and contemporary approaches. And, as it happens with good, small shows, it leaves you craving more, which is more than can be said for the Abstract Expressionism mega-survey, running almost concurrently in the main galleries below…

Omer Fast, August, (2016). Courtesy Galerie Arratia Beer / gb agency / Dvir Gallery / James Cohan Gallery / Filmgalerie 451, ©Omer Fast

Omer Fast, “Talking is not always the solution” at Marin Gropius Bau, Berlin, November 18, 2016 – March 12, 2017

“I am interested in creating my own little world and losing myself in it,” writes Omer Fast in the introduction to his survey show in Berlin, where the Israeli film and video artist also lives. And create an elliptical micro-universe he did: the works on view are connected by their plots, that at times spin new narratives around details mentioned in previous films, but also by an exhibition design that recreates waiting areas such as an airport gate or a doctor’s office where some works are screened.

It’s a heady show for anyone new to his impressive oeuvre, but for viewers more familiar with his films, the survey provides a riveting, deeper journey into his smart explorations of trauma, and human relationships in a time informed by war.

The earliest work on view, CNN Concatenated (2002), pieces together one-word cut-ups of CNN reporters to form a personal monologue about love and fear. It was made between 2000 and 2002, and so the reporting style and language change before and after the 9/11 terror attacks of 2001. Serving as an epilogue to the other works in the show—and the era—that followed, it is screened in a room set up like the waiting area of the immigration office in Berlin.

The more recent film Spring (2016) delivers new details of the backstory to Fast’s Continuity, (2012), which was commissioned for Documenta 13. And August (2016), a new work exhibited here for the first time, shows Fast’s first foray into 3D film, as well as into historical narratives. The protagonist of this dreamy, tenebrous work is the German photographer August Sander, who nearly lost his vision in old age. He is haunted by his dead son, who was captured by the Nazis for his communist views, as well as by memories of his life’s work, lost in bombings and a fire.

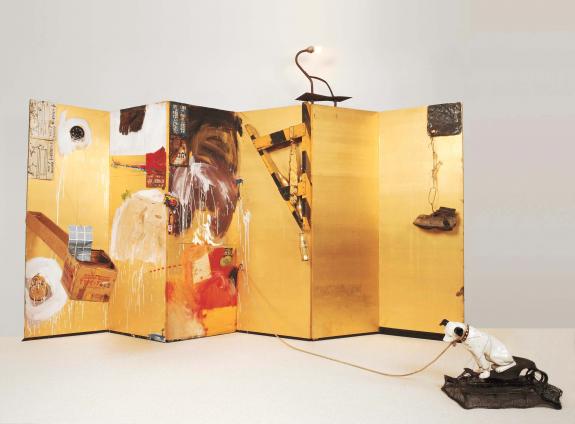

Robert Rauschenberg, Gold Standard (1964). Photograph courtesy Tate Photography. Glenstone Museum, Potomac, Maryland.

Robert Rauschenberg at Tate Modern, London, December 1, 2016 – April, 2017.

Towards the end of the year came an absolute riot of a blockbuster: Robert Rauschenberg’s much-awaited exhibition at Tate Modern, organized in collaboration with New York’s MoMA. The cold facts attest to the scope and significance of the exhibition: it’s the artist’s first posthumous retrospective since he died in 2008, and the most comprehensive survey of his work in 20 years. What’s more, some works, like his famous Monogram hadn’t traveled to the UK for over 50 years. The show gathers pretty much the bulk of his masterpieces, from Erased de Kooning Drawing and his best Combines to his performance works for E.A.T. and his later works on lightweight fabrics.

Still, the sum of its parts fails to convey the sheer exhuberance of the actual experience of seeing the show. It is rigorous, well-researched, and thorough, but it is also highly enjoyable. A much-deserved homage to a fascinating and relentless innovator who saw no boundaries between painting, sculpture, printmaking, performance, installation, and stage design, paving the way for the multidisciplinary approach to art of our current generation.