On View

A New Bronx Exhibition Celebrates Uselessness With a Suitcase That Poops and Other Unhelpful Art

These machines and machine-made art provide a philosophical counter to our market-driven economy.

These machines and machine-made art provide a philosophical counter to our market-driven economy.

Tim Schneider

Although Western culture has perhaps never been a messier pile-up of competing beliefs and conflicting opinions than it is today, few everyday sins are more reviled in America than a lack of productivity. In 2019, even artwork is often judged by certain narrow expressions of “usefulness.” How much money can it make its owner on the resale market? Is it an appealing prop for viewers’ selfies? Which social sets can one access by owning it?

But the Bronx Museum is taking a refreshingly radical approach with its new exhibition “Useless: Machines for Dreaming, Thinking, and Seeing,” which brings together a panoply of international artists using, misusing, and remixing mechanical devices to create something that’s good for nothing in the capitalist sense, but much greater in a human sense. Gerardo Mosquera, the guest curator behind the show, summarizes it this way: “It’s a reflection on how being useless could be a human achievement.”

Algis Griškevičius, The First Lithuanian Astronaut (2009). Image courtesy of the Bronx Museum.

Mosquera had the seed of the idea before his research revealed just how rich a history it carried with it. “I discovered this is a theme that has been explored by philosophers and poets and artists for ages,” he told artnet News on the eve of the exhibition’s Wednesday opening. “Aristotle was the first to say art is not useful. It doesn’t have a direct purpose.” Instead, it fulfills symbolic or spiritual purposes—and it is able to accomplish these greater ends precisely by ignoring the expectations of a system that demands every input produce a tangible, utilitarian output. Still, a sense of humor energizes the show. It is less a call for aggressive revolt against capitalism than a gleeful invitation to moon it.

Peter Fischli and David Weiss, The Way Things Go (1987). Image courtesy of the Bronx Museum.

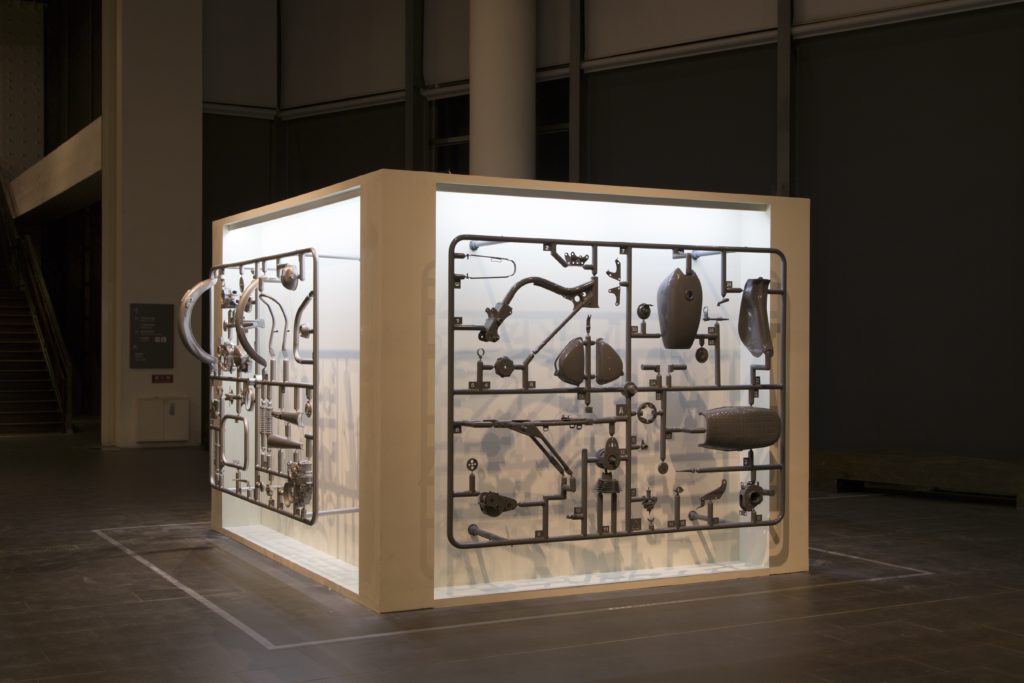

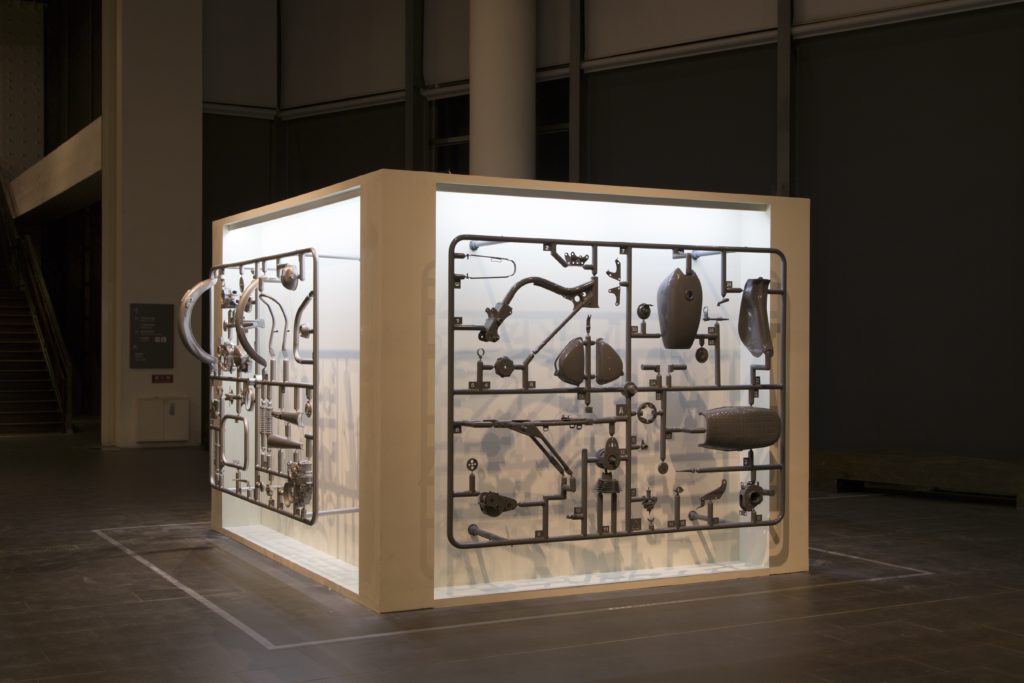

“Useless” features four different categories of works: machines specifically created by artists for aesthetic purposes, such as Wim Delvoye’s Cloaca Travel Kit, a suitcase-sized sculpture modeling a device to artificially manufacture “real” feces inside museums; pre-existing machines hijacked by artists to produce something their inventors never imagined, such as the bomb-defusing robots converted into painting machines by Fernando Sánchez Castillo; machines disassembled and reconstituted into an alternate form as ends in themselves, such as Shyu Ruey-Shiann’s Dreambox, a deconstructed motorcycle he once used to tour across Taiwan; and the results of any of these processes alone (without the device that produced them being present in the museum), such as Peter Fischli and David Weiss’s legendary The Way Things Go, a video capturing a Rube Goldberg-like chain reaction of common objects.

Wim Delvoye, Cloaca Travel Kit (2009–10). Image courtesy of the Bronx Museum.

In all cases, Mosquera chose to include only machines that were undeniably mechanical rather than more technologically advanced ones, whose elegance can mask the paradox between practical function and impractical artistry he sought to explore. Mosquera also wanted his installation decisions to be just as disruptive to the white cube aesthetic as the works themselves. The exhibition is a gloriously noisy burst of controlled chaos—an environment designed to feel “more like a workshop or factory” than a refined institutional presentation.

Despite all the moving parts, though, Mosquera stresses that kinetic art is a side issue here. “This is not about just creating a visual effect through movement or technology,” he clarifies. “I tried to have works that have a message beyond that.” Overall, the core message can perhaps best be paraphrased from an idea Mosquera includes in the catalogue essay, courtesy of Martin Heidegger: the more uncomfortable it makes us to embrace the useless, the more useful it is to do exactly that.

“Useless: Machines for Dreaming, Thinking, and Seeing” opens to the public at 6 p.m. on Wednesday, March 27 and remains on view through Sunday, September 1 at the Bronx Museum.