Art World

What Is the Art Exhibition of Your Dreams? We Asked 14 More Art-World Heavyweights

Laurie Simmons, Sean Kelly, Dan Cameron, and others imagine their fantasy shows.

Laurie Simmons, Sean Kelly, Dan Cameron, and others imagine their fantasy shows.

Artnet News

In part two of our series, artnet News asked 14 more art world aficionados to tell us: what show they’d like to see—impossible or not—in 2018? Here’s what they said.

Interior of Andrés Jaque’s “IKEA Disobedients.” Courtesy of MoMA, © Andrés Jaque.

Show: An opera directed by Andrés Jaque

An experimental opera steered by the artistic and architectural vision of Andrés Jaque of Office for Political Innovation (Madrid/New York), an architect who has a longstanding interest in performance and a truly collaborative spirit. Music by Anna Meredith and Perfume Genius. To turn it up a notch, costumes by Iris van Herpen.

Left: Douglas Gordon’s left is right and right is wrong and left is worng and right is right (1999). Photo by Stuart Tyson, © Douglas Gordon/ARS NY. Right: Stan Douglas’s Win, Place or Show (1998). Photo by Stuart Tyson, courtesy of the artist, © Stan Douglas.

Show: “The Genius Myth”

A little subversive and completely impossible would be an exhibition inspired by the genius myth. Since artists like Eva Hesse and Robert Smithson died young, we never had a chance to see them do really bad work as they got older, and so they get put on pedestals. If you were to actually do it, maybe you could pair their works with bad works by their contemporaries who lived longer, as a way of asking, What does it mean to show works that are bad, or failures? One image I showed while talking about this to a class at RISD was, on one side, Tupac Shakur, and on the other, Martha Stewart and Snoop Dogg. The Snoop of the cooking television show they do now is not the Snoop of yore, who was a more serious musician. Would Tupac have gone that route? Would Smithson have exhausted his theory of non-sites and started making Schnabel-esque paintings? We’ll never know.

Show: Female filmographies

I’d love to see a film program with back-to-back filmographies of women directors like Ida Lupino—the first female indie director/producer who made one of my favorite movies, The Hitch-Hiker (1953), and went on to direct TV shows like Have Gun Will Travel, The Twilight Zone, and Bewitched. I’d also love to see all of Doris Wishman’s 30 movies. Wishman was a screenwriter, producer, and one of the only successful female B-movie directors with a specialty in sexploitation films like Behind the Nudist Curtain, Gentlemen Prefer Nature Girls, and A Taste of Flesh. (My personal favorite is the 1961 sci-fi classic Nude On The Moon.)

Also: everything the documentarian Shirley Clarke ever made, including Portrait of Jason (1967)—a feature length interview with a gay black hustler, and The Connection (1961), a feature about heroin-addicted jazz musicians. Most of her films intentionally tested New York state censorship rules. And while we’re at it: all of Kathleen Collins’s films and Barbara Loden’s Wanda (1966).

Jennie C. Jones’s SHHH, The Red Series #2 (2014) and Electric Clef (2010). Courtesy of the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co.; Senga Nengudi’s Performance Piece (1978), performed by Maren Hassinger. Photo by Harmon Outlaw, courtesy of the artist and Thomas Erben Gallery, New York.

Show: The performative roots of visual art

I would love to see a show about performance and performativity as the basis of visual art, and as an all-woman show (though it would not have to necessarily announce itself as a feminist project). It would have to include Claude Cahun and Carolee Schneemann, and more painterly work like Jennie C. Jones, and you’d have to have Senga Nengudi. It would be international, multigenerational, cross-disciplinary. It would be wild—I can imagine a lot of it being very kinetic, and without a lot of still objects on the wall, lots of interactivity—it’s gonna be busy in there! I would love to see this show happen because it would mark a moment in which we would find support for work that is ephemeral and archival—not a big painting show of the kind that is more easily funded. That would be the sign of a much more just world.

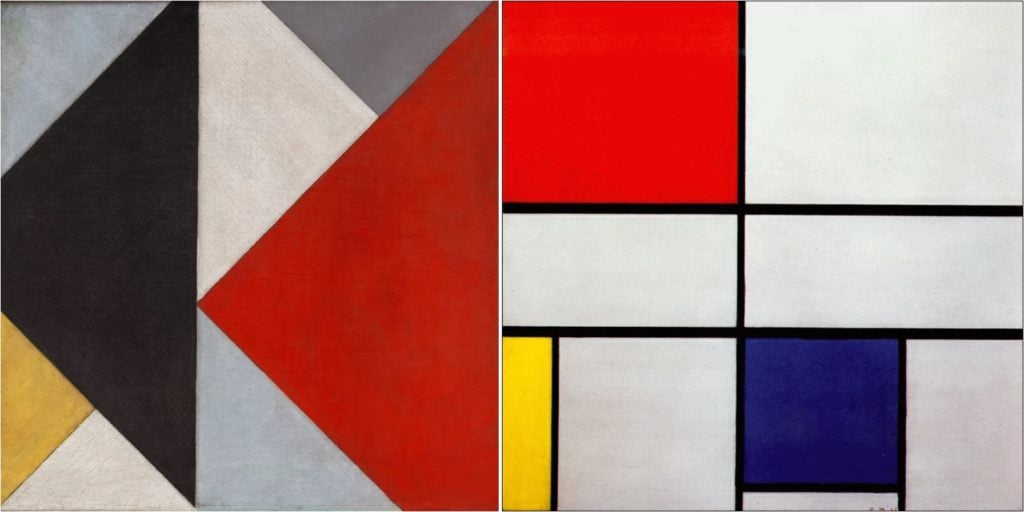

Left: Theo van Doesburg’s Counter-Composition XIII (Contra-Compositie XIII) (1925-1926). Right: Piet Mondrian’s Tableau I (1921).

Show: “Squaring the Diagonal: Van Doesburg and Mondrian”

I would love to see a show with Theo Van Doesburg and Piet Mondrian, where they put behind their quarrels around the dynamic aspect of the diagonal line. There could be a brilliantly active panel discussion on this. Similarly, a show with Alexander Calder and Bruno Munari to set aside resentments relating to novelty and originality, although I never thought Munari was very possessive with his ideas—probably because he was a fountain of them, and the value he saw in them was related to their worth for others, not their use for himself.

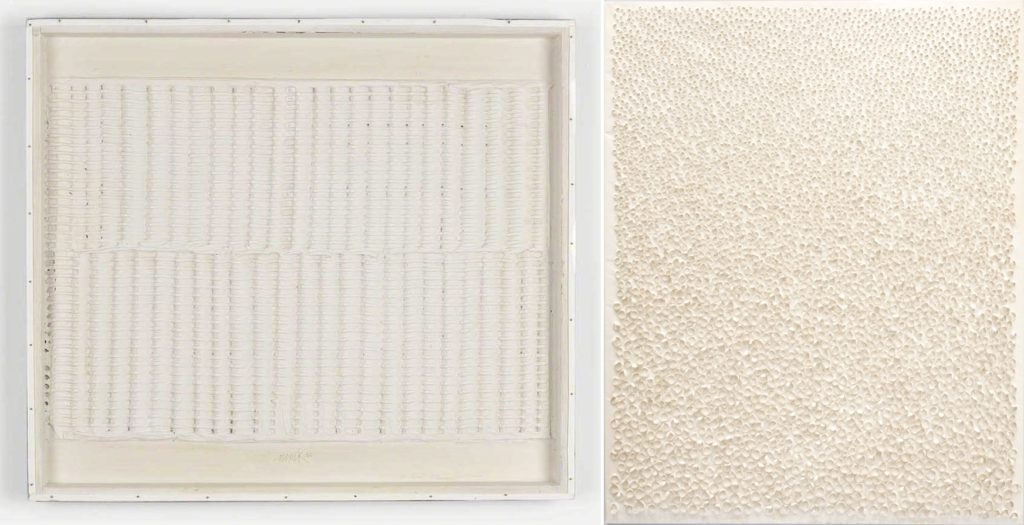

Left: Heinz Mack’s Ohne Titel (1960). Image courtesy of Perrotin Gallery. Right: Kwon Young-woo’s P80-103 (1980). Image courtesy the artist’s estate and Blum & Poe, Los Angeles.

Show: “New Frontiers: the ZERO Group and Dansaekhwa”

I would be interested to see an exhibition of both the German Zero Group and Dansaekhwa artists together. This exhibition would present the same generation of artists, mainly from 1930, who have both experienced the traumas of war. It would also look at how both groups of artists challenge tradition and explore new material, as well as how the artists came to their success—since it took a great deal of time for them to find success in their local museums before other countries started to look at their work.

Bradley Walker Tomlin’s Number 20 (1949). Courtesy of MoMA. Right: Anne Ryan’s Collage, 353 (1949). Courtesy of MoMA.

Show: 49 from ’49

Forty-nine works of art dated 1949 by the following American artists, ranging in age from 21 to 69, in the newly coined (1946) category of “abstract expressionism” (26 percent female, 26 percent non-U.S. born): Mary Abbott, William Baziotes, Forrest Bess, Ilya Bolotowsky, James Brooks, Nicolas Carone, Giorgio Cavallon, Elaine de Kooning, Willem de Kooning, Friedel Dzubas, Herbert Ferber, Perle Fine, Sam Francis, Michael Goldberg, Robert Goodnough, Arshile Gorky, Phillip Guston, Grace Hartigan, Al Held, Hans Hofmann, Carl Holty, Franz Kline, Lee Krasner, Alfred Leslie, Norman Lewis, Conrad Marca-Relli, Alice Trumbull, Mason Joan Mitchell, Robert Motherwell, Barnett Newman, Alfonso Ossorio, Charlotte Park, Ray Parker, Betty Parsons, Jackson Pollock, Richard Pousette- Dart, Ad Reinhardt, Milton Resnick, Mark Rothko, Anne Ryan, Thomas Sills, David Smith, Clyfford Still, Sylvia Stone, Myron Stout, Alma Thomas, Yvonne Thomas, Mark Tobey, Bradley Walker Tomlin.

From left: Pauline Oliveros, courtesy of the Jewish Museum; Lala Rukh’s Hieroglyphics V: Qat-jhaptaal (2008), courtesy of documenta 14; Chandralekha’s Sakambhari (1991). Credit: Bernd Merzenich.

Show: Pauline Oliveros, Lala Rukh, and Chandralekha

A dream exhibition in my view would be a collaborative exchange between composer Pauline Oliveros through her powerful methodology of “sonic awareness;” artist and founding member of the Women’s Action Forum in Lahore Lala Rukh, through her drawing scores and deep knowledge of Hindustani music; and pioneering dancer-choreographer Chandralekha, whose markings around the physicality of time and the body as energy field are most remarkable. While Oliveros and Lala were both presented at documenta 14 in Athens, they never had a chance to meet. Perhaps this fantasy project could be titled after the words of Nietzsche: “And those who were seen dancing were thought to be insane by those who could not hear the music.”

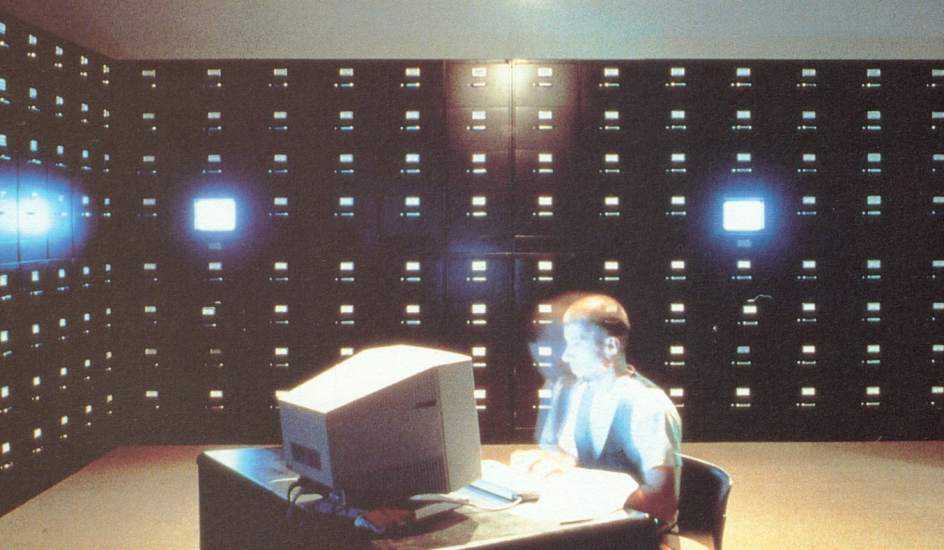

Antoni Muntadas, The File Room (1994). Courtesy of the artist.

Show: A group show of the most impactful works of all time

You know how you can (rarely, but wonderfully) walk into an exhibition and find a piece that stops you in your tracks? A piece that because it is so damned clear, and so damned true, and so damned important, you don’t forget it. It doesn’t happen often—but you know it when it does. So, my dream exhibition would include a handful of such revelatory insights, sublimely delivered. The anthropologist in me has those breakthrough moments emerging from the glorious chaos of how humans assemble themselves, and create the world we inhabit. The real kicker of course is when those insights, delivered by a specific piece, also empower us to radiate that sort of change forward. The key impact I am looking for is the inexpressible clarity that ideas in art can determine how we approach the world, and that through art, we have the power to change things.

My dream exhibition might include: Hans Haacke’s Mobilization and/or On Social Grease, which were revelatory to me as a college student reading social sciences; Muntadas’ File Room drove that understanding further, adding the collective power of contributions offered by participant viewers; Raqs Media Collective took the power of social examination and made it deeper, setting up time as a core element; SUPERFLEX blew my socks off, and still does; and then recently, Julio Cesare Morales’s work, so gentle and painful and sweet and terrible; and most recently, work by the collective Postcommodity would need to be included—perhaps their Repellent Fence (2015), a project that united every group in the highly contested war zone of the Mexican/Arizona border for 36 glorious hours.

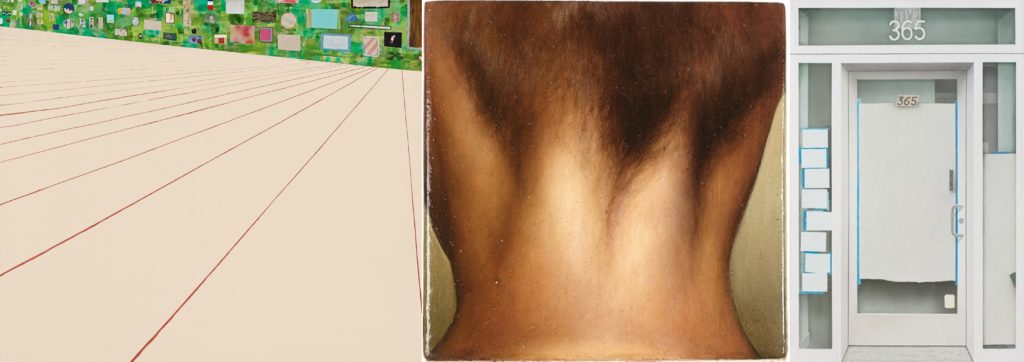

From Left: Laura Owens’s Untitled (1995). Courtesy of the Whitney Museum; Monica Majoli’s Untitled (neck) (1992). ©2018 Monica Majoli; Alexi Worth’s 365 (2014). Courtesy of the artist.

Show: On Roland Barthes’s “The Neutral”

With so much contemporary discourse framed by social media and defined by polarized overstatement, I’d love to curate a show that takes up Roland Barthes’s concept of “The Neutral:” a show of work that “baffles” dominant paradigms of art, political, and media discourse—the kind of discourse that is addicted to reinforcing dichotomous positions. The work would emphasize the extraneous and irrelevant, refusals to answer, silence, open questions, unresolved form, rejection of extremes, gradation, self-undermining, and a willingness to mock critical positions that are beneficial to oneself. Ideally, I’d include Lyubov Popova’s Constructivist Composition (1921); Willem de Koonings’s Carol Lombard (1937); Alice Neel’s Snowy Night (1938); Meredith Frampton’s Sir Charles Grant Robertson (1941); Picabia’s Women with Bulldog (1941); Ed Ruscha’s Twenty-Six Gasoline Stations (1963); Vija Celmins’s Heater (1964); Alighiero Boetti’s A Row of Merlons Set at Regular Intervals Along the Ramparts of a Wall (1971–93); Betty Tompkins’s Cow Cunt Painting #2 (1976); Lari Pittman’s How Sweet the Day, After This and That, Deep Sleep is Truly Welcomed (1988); Richard Artschwager’s White Cherokee (1991); Maureen Gallace’s Untitled (1992); Monica Majoli’s Untitled (neck) (1992); Kerry James Marshall’s 7am Sunday Morning (2003); Mary Heilman’s Mode O’Day (1991); Tomma Abts’s Thiale (2004); Laura Owens’s Untitled (1995); Charles Ray’s Two Boys (2009); Alexi Worth’s 365 (2014); William Villalongo’s Corner Office (2017), among many others.

Martín Ramírez, Untitled (1953). Courtesy of the Foundation to Promote Self Taught Art, Inc., New York. © 2017 Visko Hatfield.

Show: Parallel “outsiders”

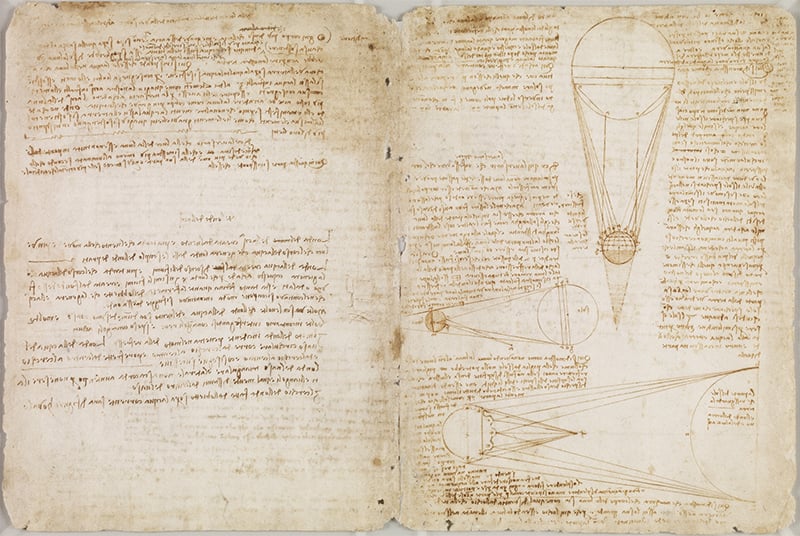

Leonardo da Vinci , a page from Codex Leicester (1506–10).

Show: Da Vinci Meets Duchamp

The exhibition I would most like to see would be one that combines the work of Leonardo da Vinci and Marcel Duchamp. Both artists produced small bodies of work, but were polymaths, as interested in the arts as the sciences. They were both elegant men, famed for their erudition and individual genius, who changed their own and our culture profoundly. Their work speaks to each other’s concerns across the millennia in a fascinating and unique manner.

Show: Artist duos—similarities, affinities, and contrasts

If I was granted the opportunity to organize a dream show, I would possibly begin by considering a group exhibition focused on various artist duos. I would place artists like Alfredo Volpi and Raoul Keyser in a room; Blinky Palermo’s work and Willy de Castro’s Objetos Ativos (Active Objects) in a different room; Forrest Bess and José Antonio da Silva in a third room, and so on. I would focus on creating dialogues driven by similarities, affinities, and obvious contrasts.

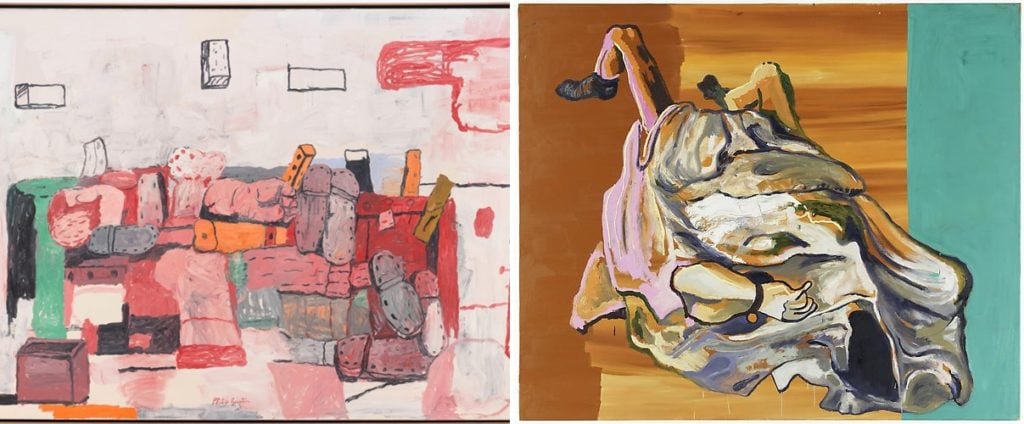

In one of these rooms there would be an exhibit focused on the last ten years of Philip Guston’s and Martin Kippenberger’s pictorial production. I have always been interested in how these artists structured their figuration on a customary matrix and applied their pictorial understanding, which I find very self-aware and elegant. Both of these exceptional draughtsman developed candid paintings that are affirmative, filled with risk and humor, and oscillate between enthusiasm and desolation. When selecting works, I would start there: customary, self-aware, elegant, risk-taking, humorous, enthusiastic and desolate. With that in mind, I would focus on the differences and particularities.

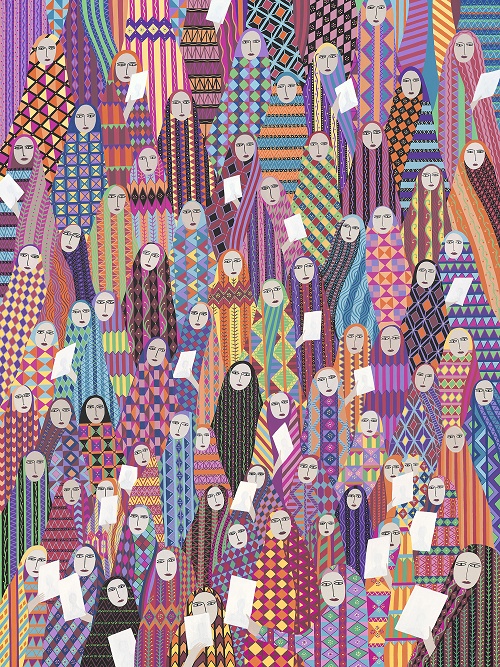

Helen Zughaib, Generations Lost. Photo courtesy of the Islamic Art Revival Series.

Show: The silent majority

Imagine an exhibition where 80 percent of participants are women, non-Western, or non-gallery artists. And imagine no mention of it in the introduction, no special focus in the press release, no pride in the speeches. Just an exhibition like many others.

Show: Erik Hanson

I think there are a lot of artists in New York City who are great and who do not have gallery representation here. But one of the best is Erik Hanson. I would like to see a major solo show of Erik’s new work—the “Bluto” paintings, which are marvelous, or a mid-career survey of his work. He’s been doing great things since the 1990s and all his older work is fresh and relevant.

Please, someone do this show.

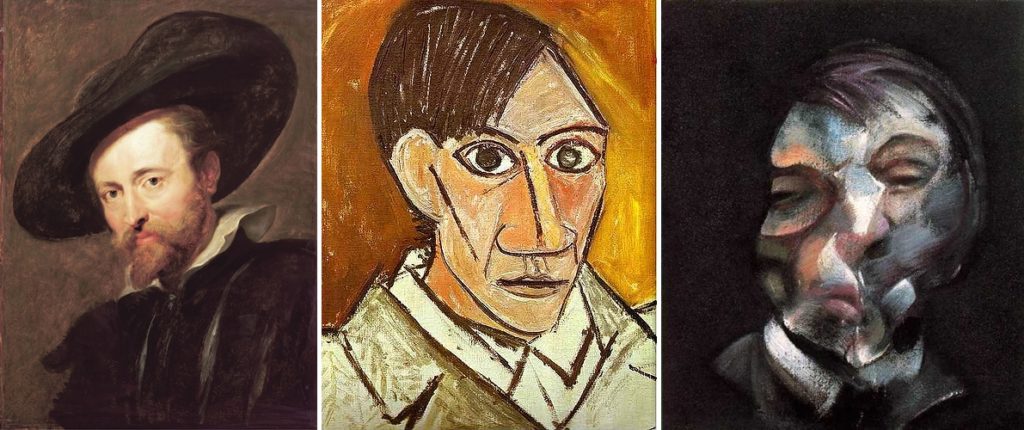

Peter Paul Rubens’s, Self Portrait (1628-1630); Pablo Picasso’s Self Portrait (1907); detail of Francis Bacon’s Self Portrait (1971).

Show: Masters old and new

I would mount an exhibition of Old Masters, modern masters, and contemporary masters. I would also love to see a show with portraits by Rubens, Picasso, and Francis Bacon.