Art World

Why Dana Schutz’s Emmett Till Painting Must Stay: A Q&A With the Whitney Biennial’s Christopher Lew

Those demanding the work's destruction are leading us down a scary path, says the show's co-curator.

Those demanding the work's destruction are leading us down a scary path, says the show's co-curator.

Andrew Goldstein

For decades, audiences have looked to the Whitney Biennial for a spinal tap of American contemporary art, using it as a way to diagnose where the aesthetic conversation is heading and, ideally, also glean something about the broader economic, social, and political winds of the time. This year, by triggering a furious, roiling debate over identity, race, artistic agency, and what it means to be politically engaged in a dangerously fluid historical moment, it has accomplished all of that, via just a single painting: Dana Schutz’s Open Casket (2016), a portrait of the disfigured corpse of Emmett Till, a black 14-year-old murdered by a Mississippi lynch mob in 1955 after a white woman falsely accused him of whistling at her.

Ever since the artist Parker Bright brought attention to the gruesome work on the show’s opening weekend, standing in front of it with a t-shirt scrawled with a Sharpie to read “Black Death Spectacle,” social media has become a pitched battlefield over whether Schutz, as a white female artist, had the right to invoke this painful visual lodestone of the Civil Rights era—or whether her claim to its power put her in a lineage of privileged white rapaciousness that goes back to and encompasses the murder itself. British artist Hannah Black (currently showing a video just a few blocks to the north of the Whitney on the glimmering tourist promenade of the High Line) suggested in a widely shared open letter that the painting be stripped from the show and destroyed. The public reckoning with Schutz and her painting has spilled out into the pages of newspapers, art journals, websites, Facebook pages, and every other stretch of the contemporary commons, with opinion split between the two poles.

In this mix, some of the vitriol in what the artist Coco Fusco termed this “multicultural melodrama” has been aimed beyond Schutz, to the Biennial curators who chose to include her work, Christopher Lew and Mia Locks. Aside from updating the wall text for Open Casket to mention the controversy, they have quietly been watching the uproar unfold—while also tending to the dozens of other artists participating in the show, which together presents a far more nuanced view of America in 2017 than the one painting.

artnet News’s editor-in-chief Andrew Goldstein spoke to Lew about Schutz, her portrait, the political moment, and the Biennial’s ambitions more broadly.

A crowd views Dana Schutz’s portrait of Emmett Till at the Whitney Biennial. Photo: Andrew Goldstein.

To begin with, your biennial opened to near-unanimous praise. Then, about a week ago, a new dynamic entered the mix. What have these past few days been like?

There’s been a huge reaction to Dana’s painting, of course. But to give some perspective, things have not slowed down since the show opened—we’re literally having lines around the block, with so many people really excited to see the Biennial, and excited to see it as an exhibition, which is the important thing.

So there’s lot of attention on the painting, yes, but this is a show that includes 62 other artists. We’ve done our second film program screening; Asad Raza has launched the weekend programs for his caretakers installation [Root sequence. Mother tongue], within which Sahra Motalebi just did a song and spoken-word performance. So there is a lot going on all around the exhibition. There are loads of tours. It’s very busy on all levels.

Asad Raza. Root Sequence, Mother Tongue (2017). Photo: Henri Neuendorf.

And yet, Dana Schutz’s painting of Emmett Till has really galvanized the public’s attention. While the art world frequently rises up in protest of social or political injustices, rarely have I seen the art community so driven by an issue as it has been by this painting. Everyone and their brother has an opinion—typically a strongly held opinion at that—and it isn’t easy to predict where someone falls on the divide. What do you make of this controversy?

I think it’s positive in the sense that people are coming to see the painting in the show, to debate the artworks that are in the show, and have these conversations around topics that are difficult to talk about. We spend our everyday lives skirting around these issues, but they’re really built into the show—we’re not running away from these discussions. So for people to be debating, protesting? It’s a good thing, and it’s a powerful thing.

But I think to have a discussion around the destruction of an artwork is deeply problematic and disturbing—that’s not something that we entertain as a museum. In terms of discussing what is in the show and the artists’ intentions, on the other hand, that’s important to discuss, and that’s very much a part of the biennial.

Before we talk about the painting itself, let’s go back to the genesis of this show. When did you and Mia finalize the outlines of your curatorial presentation, and what were the social factors that came into play in guiding your selections?

We started in the fall of 2015, when the announcement went out and we put together our curatorial advisory group. The bulk of our research and our travel portion took place in the first half of 2016, so we knew that whatever would come of the election would be something that we couldn’t anticipate, in terms of how it would set a context for the show. We never set out to make a show about an election anyway. But the conversations we had in the first half of last year really informed what we arrived at with the exhibition, and we saw so many artists doing work across the gamut—from studio-based practices to literally doing performances out in the street, like Maya Stovall—who are all thinking about what is happening right now in society, and in the US in particular.

Maya Stovall, still from Liquor Store Theatre Vol. 1 (2014). Courtesy the artist, Eric Johnston, and Todd Stovall. Photograph by Eric Johnston.

They are thinking about what artists can do in these times, how they speak to the world, and, in some instances, how within the private space of a studio they can still address things that are beyond the studio. Many of these artists were seeking a direct engagement with what was happening on the street.

For example, John Riepenhoff has been thinking about how he can support a community of artists—in Milwaukee, in his case—through work that literally becomes a support for other artists. Or, going to Puerto Rico, we found an inspiring artist space called Beta-Local that was formed by a group of artists to create the kinds of discursive resources that were not available on the island, like residencies, educational programs, and experimental workshops.

Works from John Riepenhoff’s “Handler” series. Image: Ben Davis.

A lot of this infused our thinking, how artists are engaging with the world by recognizing the forces that are pulling people apart, whether they be economic forces, inequalities, or issues around social justice or racialized violence. This is very much the time of Black Lives Matter, which is an important touchstone as well. We were interested in this idea of how artists were addressing a lack of social infrastructure, or civic-ness, within a specific place or community at a time when governments are no longer fulfilling these roles. These conditions, both good and bad, were markers of our current times in the US.

I think it’s useful to remember back to this time, in the summer of 2016, because the furious churn of the news cycle has propelled the national psyche to a different place since then. The country was in a state of extreme trauma. Terrorist attacks in Europe and at home had everyone on edge, police were brutally killing black men in the streets, protests were blazing across America, and specters of the gruesome 20th century were reappearing in headlines in the form of Nazi rallies, white supremacists, and the Ku Klux Klan. Add to this the yawning economic polarization between the classes and it truly felt like society was falling apart—a climate that Donald Trump exploited with his call to a ferocious, nativist populism. Your show seems to specifically address this horrific moment, for instance with another Dana Schutz painting that greets visitors as they reach the fifth floor: a painting of people crammed in an elevator, literally tearing each other limb from limb, evidently out of rage born by pure proximity. Why did you commission that painting specially for the show?

It speaks to the heatedness in the US and the world at large over the last year or two—those issues you point out that are not new to the country but have become recently more visible. Dana had already been working on a series of elevator paintings, so we weren’t asking her to create something completely new, only to think of an elevator painting in the context of the Whitney—to think about the size of our art elevator and to use that as a launching point.

Dana Schutz Elevator (2017). Photo by Henri Neuendorf.

We had it in our heads early on that if one were to take the large elevator up to the fifth floor—perhaps being jostled on the elevator, kind of like in the subway at rush hour—one would see a painting that comments on the experience. The painting and the elevator kind of serve as a metaphor for society, for the country—we’re all crammed together and you either fight for your life or come together and work. If you look closely at that painting, as just one reading of the work, there’s someone applying wallpaper in the corner of the elevator—so despite all of the tumult, things can still get done. There are also insects—saying, in a sense, that we’re not alone in the world.

I think if a viewer spends a good amount of time looking at the work in the show, they’re going to come away shaken by the amount of violence there is in the artworks. From Jordan Wolfson’s Real Violence and its VR depiction of an extraordinarily brutal beating to Porpentine Charity Heartscape’s Cyberqueen (2012)—a video game that plays like a visceral horror movie—to Henry Taylor’s portrait of a slain Philando Castile, and then to Dana Schutz’s painting of Emmett Till, gut-wrenching violence is pervasive in the show. Was that intentional?

Henry Taylor, THE TIMES THAY AINT A CHANGING, FAST ENOUGH! (2017). Photo by Henri Neuendorf.

It’s not just violence on its own. If you look at the room with Taylor’s piece, there is that depiction of a murderous act in the death of Castile, but that’s set within the context of Henry’s large painting of the Fourth of July and his painting of his mother with a horse in the background, together with the photographs of Deana Lawson that point to a sense of dignity, love, and self-respect.

Deana Lawson, Ring Bearer (2016). Collection of the artist. Courtesy Rhona Hoffman and Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

So, the violence is set within other aspects of the human condition and human experience—violence and death is there, but so is love, unity, self-preservation, and self-care. The strands of violence are there, but they’re also set alongside a restorative sensibility. For instance, Asad Raza’s installation is in the room right next to Jordan’s, so you can imagine experiencing Jordan’s work and then entering a grove of trees with caretakers who are interacting in a one-on-one therapeutic way.

Visitors experiencing Jordan Wolfson’s Real Violence (2017) virtual reality artwork. Photo: Henri Neuendorf.

Wolfson’s virtual-reality piece is completely shocking, and in fact some commenters in the controversy over the Emmett Till painting have voiced incredulity that there isn’t more outrage over that artwork. In it, you watch the artist very realistically bludgeon another man’s head with a baseball bat, apparently killing him on the street in broad daylight while a childlike voice sings a Hebrew prayer. My reading of it is that, amid the surge in worldwide anti-Semitism, Wolfson is sublimating his feeling of vulnerability into furious anger and aggression—like the Bear Jew in Inglorious Basterds—only without a clear, deserving villain for his wrath, just a nondescript white-guy victim. The piece forces the viewer to witness this sadistic act.

That’s one way to read it. It’s a difficult piece, but one of the things that VR allows for is that you can turn your head—you can turn away and not see it. There’s still a lack of agency on the part of the viewer, so you can’t actually step in and stop the beating, but you do have the choice to not watch it, and I think that is one of the things that Jordan makes apparent. You can turn and look the other way, which kind of speaks to being a bystander who does nothing, or refuses to witness something—but I think that adds another level of generative ambiguity to the piece.

Visitors playing experimental videogames by Porpentine Charity Heartscape With Those We Love Alive (2014). Photo: Henri Neuendorf.

And there is definitely a sense of empathy in other pieces in the show, especially in something like Porpentine’s games, where if you play Ultra Business Tycoon III long enough it stops being just about making money and robbing from one corporation for another; the game has a kind of rupture when you realize it’s not just about you as the player but also about your sister who is about to leave the family and run away, and all you can do is turn back and continue to play the game. Her pieces really speak to these issues of trauma or PTSD, in which these difficult emotions are couched in video games and use fantasy or science fiction to reach an empathetic space, through art.

That dichotomy of violence and empathy is something that really comes across in the show. The societal traumas we were talking about are powerfully present, but what I was struck by in the Biennial is that the artists seem to be coming into this rupture like white blood cells, trying to heal the wounds. There is a real ameliorative sensibility in a lot of the projects in the show, with the artists trying to work through how we can bridge the divides through empathy.

And I think that brings us to Schutz’s portrait of Emmett Till. It’s fascinating that if you look at this now-famous painting in person, you see that it’s of course an abstracted evocation of a hideous, abominable murder, but you also notice that it’s not a flat painting but actually literally vaulting out into the world, giving the image a real symbolic weight or presence.

Yeah, that’s something that gets lost when you’re looking at an image of a painting. Many of the intense reactions—which are understandable as the work deals with a very difficult and painful subject—have been based on internet images, and the majority of the people speaking about it haven’t seen the painting in person, in a gallery where it’s set in dialogue with other works.

For me, whenever I’m standing in front of the painting, it brings about a real sense of loss. It really evokes the feeling of mourning for a real person who has died. It was that feeling, when I saw it for the first time in Dana’s studio, that allowed me to think about the painting in a way that would fit into the Biennial, within a constellation of artworks that could speak to these issues in a deeply meaningful and deeply sad and empathetic way—in a similar way that Henry Taylor’s painting does and in a somewhat different way An-My Lê’s photographs.

Photos by An-My Lê in the Whitney Biennial 2017. Photo: Henri Neuendorf.

How did you come to hear about Parker Bright’s protest, and then Hannah Black’s letter?

Parker’s protest happened on a Friday and Saturday for a few hours, and the museum knew that it was going on and our staff informed us. The museum let him voice his concerns, and he was doing it in a very responsible and respectful way, engaging with visitors and having discussions around the painting. Some of the things he was bringing up were not entirely accurate, like the value of the painting or Dana’s intention to sell it, which was never the case—she made it clear from the beginning, when it was first shown at Contemporary Fine Arts in Berlin, that she never intended to sell it. But the fact that he was having discussions with real people in the gallery, that’s something that we want, so in no way did we impede that from happening.

Hannah’s petition called for the destruction of an artwork. As a museum with a collection, with the role of being custodians for art, we can never condone the destruction of a work. It’s such an extreme demand that it brings things to the point where one can’t have a real conversation.

The other thing about the work—the history that Dana is tapping into with the work, the lynching and murder of Emmett Till—is that this is a history that is an American history. Certainly people of different races have different experiences, but this historic and contemporary violence is something that we all have to grapple with and confront. It is deeply painful and traumatic—more so for some than others, in unequal terms—but it is something that we all have to deal with, and I think if we don’t confront it, if we don’t have these kind of conversations, then we’re not getting anywhere.

In Black’s letter she writes that “non-Black people must accept that they will never embody and cannot understand this gesture,” referring to Mamie Till’s display of her son’s body. That is a categorical denial of the ability of anyone whose body is not black to empathize with a fundamentally human act of grief and sorrow. On the one hand, you have a rash of police shootings across the country where officers rationalize their extreme violence through an otherizing of their victims—as in the murder of the teenage Michael Brown, who Officer Darren Wilson described as an almost supernatural threat—and on the other hand you have Schutz in her studio, laboriously and over hours looking back and forth between the photograph of Till’s corpse and her canvas, building up paint to convey her identification with his bereft mother.

If we do not see the humanity in one another, that’s when we end up with divisions and barriers. In many ways, it goes back to when we could only see 3/5 of a person. That’s what has led us down this path to where we can no longer empathize or even speak to each other. To police these barriers takes us down a dangerous path, moving us away from the very ideals of what this country can be.

Certainly there is a violent history of the United States, which is very real, and we still feel it today. But there are also certain ideals in which we can bridge these divides and try to come together, and I think the show tries to speak to both of those things. The artists bring to light both of those paradoxical conditions that exist within the country.

Many people have expressed feeling intense emotional pain upon seeing this painting, which has now been distributed far and wide online. In a way, Dana Schutz’s act of empathy has been transmuted into its opposite—into an act of aggression, yielding a new trauma. Some people who are furious about the painting place their blame at the feet of Schutz, saying that she should never have made this painting, that she had no right, that it should be burned. Other people, like the artist and curator Micah Silver, contend that the blame does not lie with her—that she could have made this painting in the dark of her studio and everything would have been fine had it never seen the light of day. Instead, the argument goes, the fault is with the Whitney and the Biennial’s curators for choosing to display it. What is your reaction to that?

I don’t think there is any blame to be laid, period. Mia and I have conscientiously thought through every work that is in the show, and we believe in the painting that Dana made. Certainly we knew that it could be traumatic—certainly it’s a difficult painting to look at—and there are works in the show like hers or Jordan’s that can be problematic for people. But, for us, they are both so woven into a dialogue about representation, about issues of violence that are both historical and contemporary, and about this idea of empathy—and these are all shared concerns across a diverse group of artists. They are not concerns that are broken and divided by race. They are American concerns.

Aliza Nisenbaum, Latin Runners Club (2016). Image: Ben Davis.

If you think of an artist like Aliza Nisenbaum, who is depicting the everyday life of immigrants, she is encouraging us to empathize with those figures—and, you know, not everybody knows what it’s like to be an immigrant either, but what we see in her work allows us to open up a door and to perhaps see the injustice of the bans that are being advanced right now in this country. These are conversations that we need to have right now, together. Otherwise literal doors are closing, and we will no longer be able to speak to each other.

In a way, this Dana Schutz controversy reminds me of what we saw happen during this election, where a snippet of a politician’s quote would be taken out of context and disseminated online to reliably generate tremendous outrage—whereas if you see it within its proper context, it starts to make more sense. To your and Mia’s credit, your Biennial anticipates this kind of reaction. For one thing, you have Puppies Puppies’s trio of gun triggers—titled Trigger (Glock 22) (Permanently Disabled by Chip Flynn)—that reference the idea of the “trigger,” or unwanted encounter with something that is traumatic, an idea that is so polarizing on college campuses these days.

Yeah, exactly. Puppies Puppies’s triggers point to the idea of trigger warnings—but also the fact that Puppies is removing triggers from actual guns in order to take those weapons out of circulation adds another element to those works.

Puppies Puppies, Trigger (Glock 22) (Permanently Disabled by Chip Flynn) (2016). Kourosh Larizadeh and Luis Pardo Collection; courtesy the artist and What Pipeline.

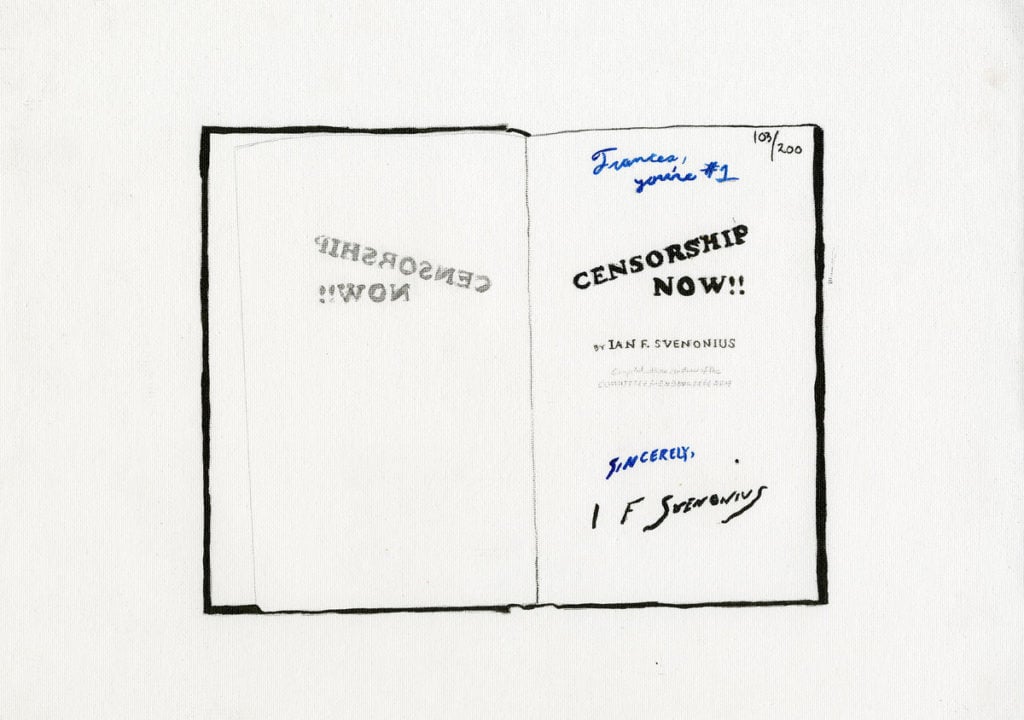

Then you also have Frances Stark’s cycle of paintings presenting Ian Svenonius’s “Censorship” text, which is a remarkable, complex piece that almost prophetically echoes the calls to destroy Schutz’s painting. What is going on in that piece?

Frances has been longtime friends with Ian Svenonius, who is the writer of the essay and also a musician—he was part of Nation of Ulysses, the DC Post-punk band. He has been thinking a lot around these issues. So, when we started speaking with Frances, we had in mind certain directions that the biennial could point towards like activism within higher education, especially at USC and Cooper Union. She came back to us and said, “I want to make a cycle of paintings around Ian’s essay,” which for her has been so important.

Frances Stark, study for Censorship Now (2006. Courtesy the artist.

Ian’s essay is so interesting because parts of it feel satirical, some of it is parodic, but some of it feels very earnest too—and it moves between these registers, so every line carries within it all of those tones. What Ian is saying is that freedom of expression doesn’t actually help the arts and instead we need censorship, that art needs to be policed in order for it to have agency and to have an effective voice.

Of course, this was before Trump and before all of these threats to defund arts and humanities. Now, to have this kind of dynamic play out around Dana’s painting, it underscores a sense of urgency—what happens if people are demanding that a work is taken off the walls and destroyed, or that we no longer have support for arts and culture by government? If it’s becoming much harder to get the voices of artists out into the world, how much more important are those voices now? And we have seen what happens when the freedom of expression gets closed down—look at what groups historically have called for certain artworks not to be shown, or to be destroyed. Those have been very scary groups.

It’s a strange confluence, this idea of extreme political correctness on one side and extreme anti-intellectualism and xenophobia on the other side. The middle is squeezed between two orthodoxies. At the same time, it’s clear we’re entering a new culture war where the old rules of engagement no longer apply. Why do you think this situation feels so unusual and new?

I think it’s because the speed in which it happens, in terms of debate online, is so much faster than what you would have in traditional media. Think of where these debates typically have occurred in the past. There once were real partisan debates in government, and newspapers and traditional journals would be another site for these conversations, providing a sense of a public commons where one debated various sides of issues. That is no longer happening in these types of venues, the political parties are not speaking to each other, and we’re all consuming our news in bubbles that only show us the type of information we want to see.

Now, in a way, these types of debates are happening in museums—they are some of the last few physical places where people can convene to wrestle with ideas. In that sense, institutions like museums are able to host a more generative conversation. Maybe because we’re not seeing it in these other places, so many people are coming to museums to see artwork and socialize, but also to have a certain forum that doesn’t exist in real space elsewhere.

How has attendance been for the Biennial so far?

Attendance has been great. It’s exciting just to see so many people come to the museum. I haven’t seen numbers yet, but you can feel it, like on a Monday morning when the lines are down the block.

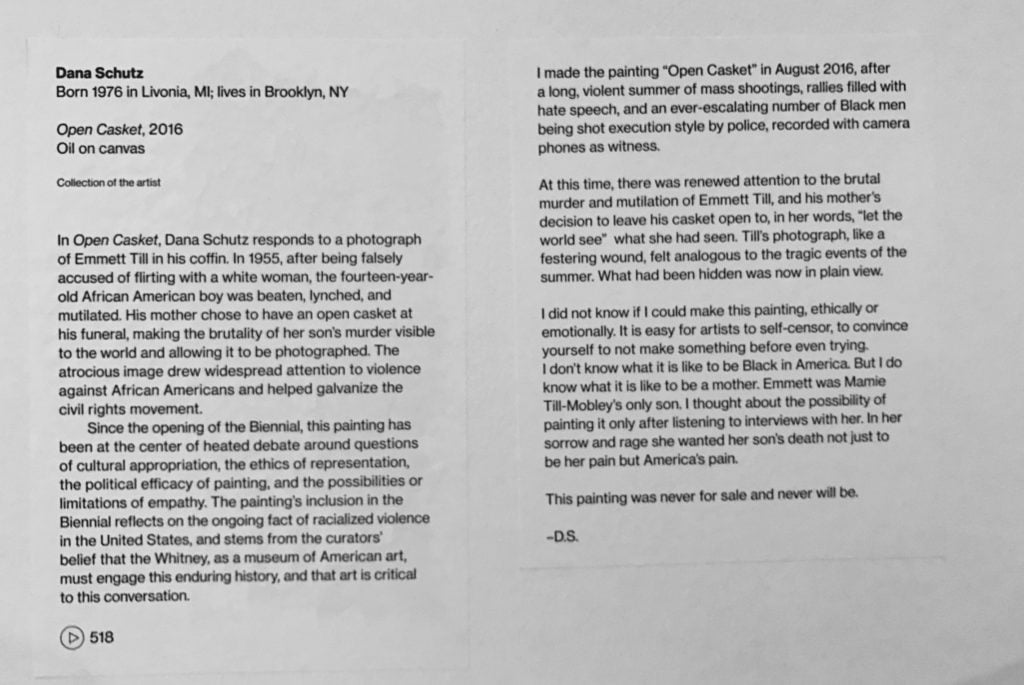

I’m sure many people are making a beeline to the Schutz painting, and I noticed you changed the label to add a note about the controversy and to include a statement by the artist. When did you do that?

When we met with Parker Bright, one thing he said was that there wasn’t enough context for the painting, and so we provided more context. We took that to heart and we provided more context. We realized we needed to provide more information, but also to take note that there is protest and debate around the work, and to add reasons why, as curators, Mia and I chose to put this work in the show. We understood that was important.

The updated label for Dana Schutz’s Open Casket at the Whitney Biennial 2017. Image: Andrew Goldstein.

Have you been in contact with Hannah Black?

Not directly, no.

Do you think this controversy is going to define the Biennial? And, if so, are you okay with that?

What will be talked about, or written, or what defines the Biennial is not up to me. We are the co-curators of the Biennial, but it tells its story, and it’s up to other people to interpret what the show is saying.

Have you learned anything new about the way that art is functioning today?

You know, it feels good that people are paying attention, that people really care about the Biennial. If people are really going to think hard, to debate and talk both within the galleries and outside the museum, that’s a great thing—and that’s what’s been so exciting. People do care, and care deeply, no matter what perspective and what your take is on the show. We need more of that.