As a student at Stanford University in 1994, the Chinese-American programmer Jerry Yang and his friend David Filo compiled a directory for the budding Internet called “Jerry and David’s Guide to the World Wide Web”—an unwieldy title that was later shortened to Yahoo!, the exuberant company that helped pioneer the transformative field of search.

Three years later, Yang visited China for the first time, taking a tour of the Great Wall from a young onetime English teacher named Jack Ma, who later went on to found the Chinese online store for everything, Alibaba.

These pivotal moments—which positioned Yang to land one of the great business coups of recent decades when he persuaded Yahoo! to buy two-fifths of Alibaba in 2005—elevated the entrepreneur to the upper echelon of Silicon Valley tech and gave him a front-row seat to one the greatest success stories in China’s rocket-fueled economic resurgence. It also left him with a fortune of roughly $2.3 billion, some of which he has used to build an extraordinary art collection that he hopes will help bridge the two cultures that have defined his life: Asia and the United States.

This month, a small slice of the collection Yang has built with his wife Akiko Yamazaki is on view at Stanford University’s Cantor Art Center. Called “Ink Worlds,” the show aims to educate audiences about the vibrant tradition of modern Asian ink painting, stretching from the 1960s to today.

Yang’s own personal taste tends toward calligraphy, a subject that yielded an earlier collection show called “Out of Character” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and San Francisco’s Asian Art Museum in 2012. Last fall, Yang and his wife gave a historic gift of $25 million to the Asian Art Museum—the largest donation in the museum’s history. (They also gave a larger gift of $75 million to Stanford a decade ago to create the Jerry Yang and Akiko Yamazaki Environment and Energy Building, demonstrating that their philanthropy is multidimensional.)

Now funding early-stage technology startups through his venture capital firm AME Cloud Ventures, Yang has surprisingly cutting-edge ambitions for his patronage of pen-and-ink-on-paper artworks. Andrew Goldstein, artnet News’s editor-in-chief, spoke to the Yahoo! co-founder to find out more about his vision and how to appreciate the exquisitely refined art forms he collects.

Jerry Yang and his wife Akiko (left). Photo courtesy of Jerry Yang.

You are a tremendously accomplished collector of calligraphy. It’s a genre that occupies a central position in the art of China, but is not very well understood in the United States. Can you tell me how you began to collect calligraphy? How does it differ from Chinese ink painting, another hugely important artistic category?

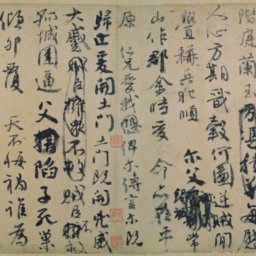

All the great collections in China, for a thousand years or so, have always had a little bit of both ink and calligraphy. That goes back to the first time somebody picked up a brush and filled it with ink and doodled on a piece of paper. So our approach is unconventional in the sense that when I started collecting, I was primarily interested in calligraphy, and not the traditional painting side.

There isn’t really a real reason for this, although it happens that I practiced calligraphy when I was a child—I wasn’t very good at it—but I felt like it was an art form that I had some very superficial familiarity with. At the time when I started collecting, Chinese paintings were a very well-studied, very sophisticated collector’s pursuit, and there were many, many other collectors that had amassed wonderful collections of paintings and calligraphy. I felt I didn’t have the eye or the expertise to appreciate traditional painting.

At the same time, while calligraphy was really my thing, collecting contemporary artists who work in the Chinese ink tradition was something that my wife Akiko and I had started doing together. The contemporary approaches to the traditional art form of painting with a brush and ink on rice paper really captured our imagination.

So we ended up having a collection of calligraphy that is mostly older stuff, from the 13th century to the 19th century, and then we have this collection of contemporary ink painting that is mostly by Chinese or Chinese-American artists who are using traditional ink techniques. The show at Stanford now focuses on the contemporary aspect, but for us they’re tied together because they relate to the same tradition and also, in some ways, to the literati way of collecting.

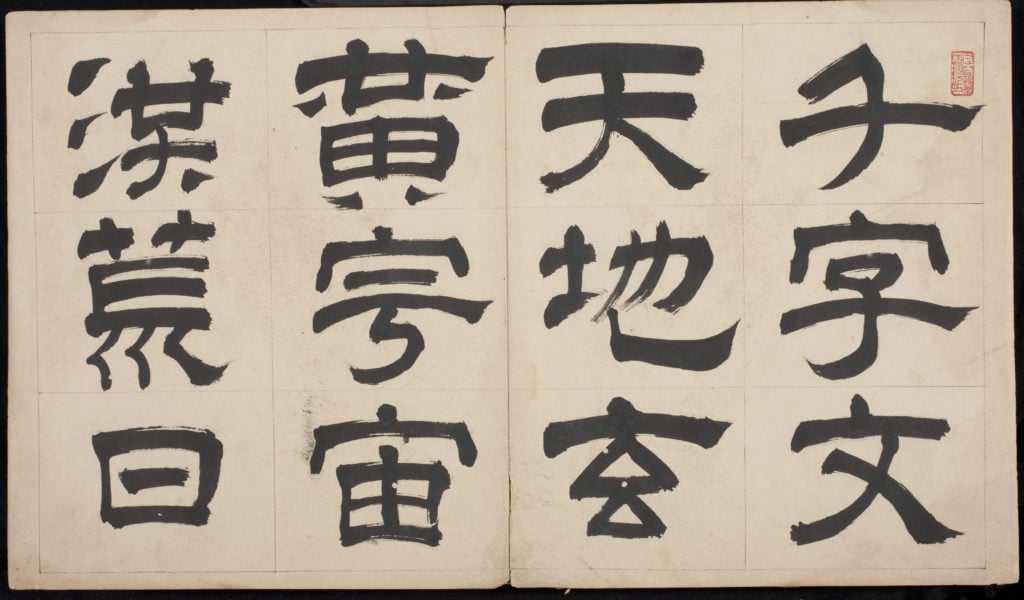

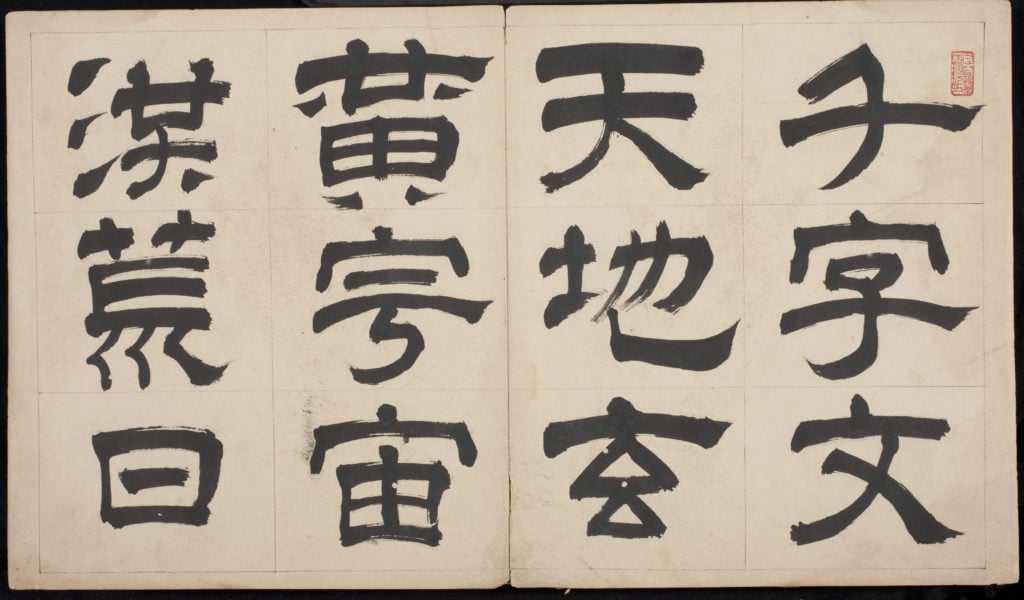

Thousand Character Essay, in clerical script. By Wen Peng, 1498-1573. Album of 85 double leaves, ink on paper. Photography by Kaz Tsuruta.

When you say “the literati way of collecting,” what do you mean? Can you explain a bit more about the context calligraphy is viewed within, and why the form is so prized in China?

There is some calligraphy in Western culture, but it’s viewed as a form of decorative art, not a sort of high form of art. In China, on the other hand, calligraphy is a form that is largely practiced by people who are well educated, but also it’s a way of expressing multiple layers of meaning, not just its content.

For example, if you look at Western calligraphy, there are some ways of personalizing one’s style, but it largely looks the same. In the Chinese form, while there are standard ways of writing characters and standard ways of writing certain scripts, the expression of the individual artist is really embodied in the work of the great calligraphers.

Through the 17th century, most of the people who could write in calligraphy were scholars, because the common people couldn’t really write—well, they could write, but they were writing for fun, they weren’t writing for serious ends. So it became prized even in these early days, with people in the 13th century collecting calligraphy from the 10th century, and people in the 10th century collecting from the 4th century. A tradition of collecting emerged from the beginning.

Calligraphers were trying to model their work after the ancients—to take old masters and learn to imitate them and then try to surpass them. This cycle of learning by copying, learning by imitation, and then eventually creating your own style through practice defines both calligraphy and painting in China for the last 1,500 years or so.

And because it’s been collected through the centuries, and because it’s such an expression of the individual personalities of those who have mastered it, it’s viewed as the highest art form. At least, that’s part of why it’s viewed that way.

You mentioned that calligraphy is viewed in the West more as decorative art. But I would think that a major reason for this is that our form of written language is far less complex, and complexly visual, than in China, where language is rendered in logograms of tremendous visual variety. And so I wonder, what to you marks a truly great piece of calligraphic art? How can you tell a masterful piece of calligraphy from one that is less masterful?

You raise a great point. If you look at phonetic languages, there is less room for creativity in calligraphy—although there’s also some great Japanese calligraphy being done using their phonetic language. But with Chinese calligraphy, there is some more stylistic freedom—like you can take something that means sky and stylistically make it look light and airy.

To answer your question about what makes great calligraphy, first I should point out that in Chinese culture today, there is plenty of calligraphy used as decorative art. You walk around people’s houses and they have calligraphy hanging on doors. But when you see the great ones, it’s evident that they are unique.

How can you tell?

There are a few layers of what makes great calligraphy great. One is the calligrapher himself or herself. It’s a little bit like Western art in that you first have to go through training to establish yourself as a competent calligrapher, and you have to be able to copy the ancient masters. It’s not like I could take a piece of paper and start writing things and if my style looks kind of unique I can be recognized as a great calligrapher—you have to be able to write beautifully in the style of the older generation before you can create your own style. Just as before you can become an abstract painter, you have to learn how to draw.

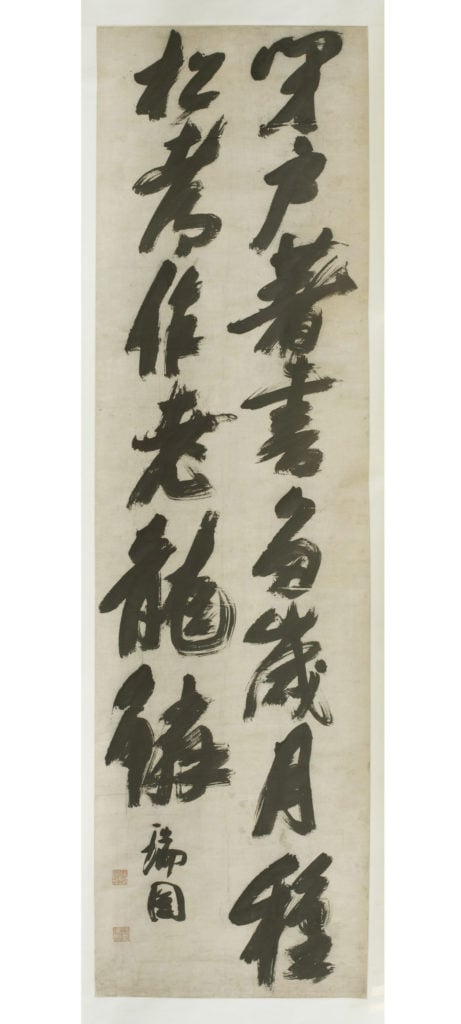

The second step is that they take the ancient masters’ style and advance it. Generally that means breaking with part of the tradition, which is brave in some cases, and which sometimes can be reflective of the times. They can also marry styles, which then become accepted. Because it’s one thing to break with tradition, it’s another thing to gain acceptance from one’s peers in one’s time. That wasn’t always the case—there were some calligraphers who broke the mold and weren’t accepted in their time, only being viewed as great decades or hundreds of years later. In other words, not only does a calligrapher have to hope that their peers accept the work as great, history, over hundreds of years, also has to accept it as great.

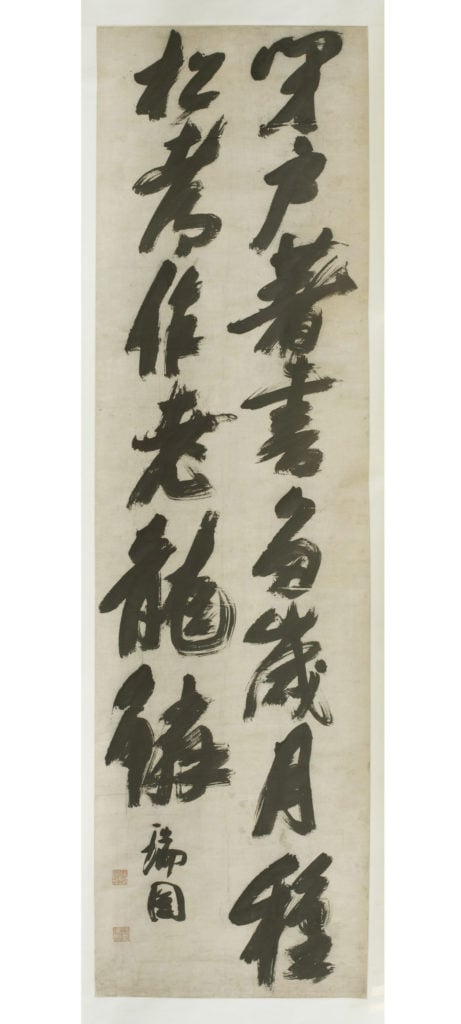

Poetic lines, in semicursive script. By Zhang Ruitu, 1570-1641. Hanging scroll, ink on paper. Photography by Kaz Tsuruta.

That’s a dauntingly high bar.

Yes. It just shows that there’s so much more to appreciating calligraphy than just looking at it—you really need to understand the history of the calligrapher, and his or her experiences, and also his or her credibility.

Then, of course, there are technical considerations like the movements of the brush, the way that the masters float across paper, the way they use different kinds of ink with different degrees of force—for instance, you can tell how strongly or how fast they wrote.

Finally, there’s the content of what they were writing, which is also very important—so besides the graphical elements, you also take into account the meaning, and the occasion for the work.

Now, depending on the audience, there are also layers of appreciation. For a Western audience, they might appreciate a piece of calligraphy because it looks abstract, or wild—it might look like a Twombly or a Franz Kline. In fact, Franz Kline talked about being influenced by Asian calligraphy. When we had our show at the Met, we actually had some works of Western abstract art being displayed next to the calligraphy, and it was kind of a knockout as two examples of graphical abstract art, if you will. But then for those people who understand some of the language or the technique or the history or the context, there are so many more layers that they can peel off and appreciate.

What would you say is the most prized piece in your collection?

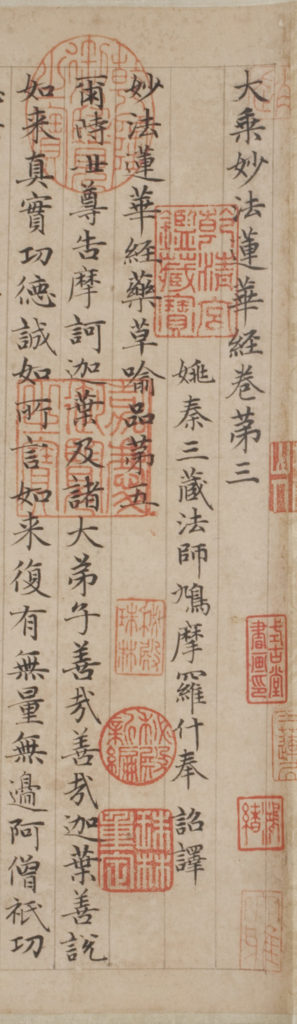

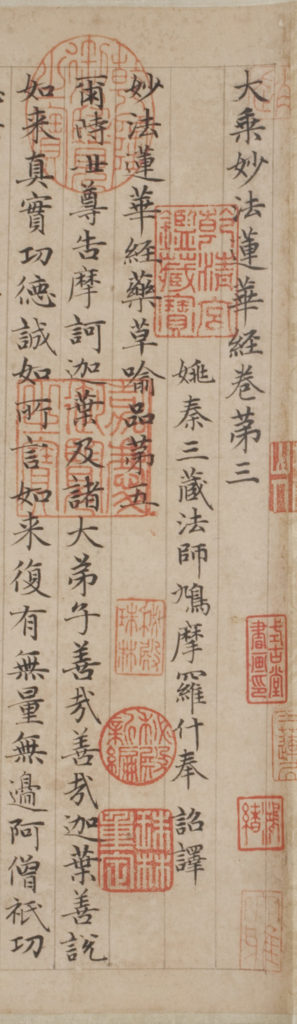

You know, it’s hard pick among your kids, as they say, but there are certainly some monumental works that are representative of the collection. The one that was on the cover of the catalogue is an early 14th-century masterpiece by a very, very famous artist named Zhao Mengfu. Zhao was probably the most important Yuan dynasty artist, and he wrote this Lotus sutra for his master [The Sūtra on the Lotus of the Sublime Dharma] in seven volumes, and we have volume three.

Our volume has obviously been around for 700 years now, and it was in the collection of the Qing imperial court. It’s in small standard script, and it runs for about 50,000 characters, all of which were written for his master as a tribute, a sign of respect, and as a form of meditation—it has all the stuff that was embodied by Buddhism at the time. It’s not quite clear how long it took him to write it, but he was 61 when he began, so it’s quite an impressive feat.

If I were to pick one work from my collection, that’s probably the most recognized and most important one, even though there are others that are large in size or are masterpieces because they are the culmination of an artist’s work.

The Sutra on the Lotus of the Sublime Dharma (Miaofa lianhua jing), in small standard script. By Zhao Mengfu, 1254-1322. Handscroll, number 3 of a set of 7, ink on paper. Photography by Kaz Tsuruta.

In the art business, much is made about how slowly the elite of Silicon Valley have become collectors of art, especially in contrast to other fields like finance where there is a more established tradition of art-collecting and patronage. Last year, however, you and your wife Akiko Yamazaki pledged $25 million to San Francisco’s Asian Art Museum. Of all the different causes you could fund, why art? Why do you feel that art is important to support?

Well, I would say that we’re selfish in our altruism, because we pick causes that we have a personal connection to. We’ve supported energy and the environment because Akiko is very much into conservation of wildlife, and I’m very into sustainability and security. But if we don’t worry about it in our lifetimes, then our kids and their kids are going to have to worry about it, so there’s a practical element to it, too.

Art, for us, is also not just about appreciation and collecting. We’ve focused on Asian art—we don’t have much Western art—because it reflects our heritage, since Akiku is Japanese and I’m Chinese, and it allows us to be Americans in America and also have a link to our past and to the current culture.

Our show at Stanford right now, for instance, reflects the last 30 years going back to 1989 and Tiananmen Square, when many artists left China and made their work in the United States. A lot of it is peaceful art on the outside, but full of struggle, especially when you know the artists’ personal history. China will keep changing, and the world will keep changing, but I don’t know if we’ll ever see anything like those last 30 years again, certainly without something extraordinarily shocking happening externally.

And then the reason we’re doing exhibitions like the calligraphy show or the one at Stanford—or putting part of our calligraphy collection on exhibit in places like Kansas City and Cleveland—is that our goal is really to contribute to the dialogue around Asian art and Asian culture in America. We believe that, through art, we can talk about things that may or may not be possible to discuss otherwise, so there is an altruistic angle as well.

Zheng Chongbin‘s Chimeric Landscape, 2015. Multimedia installation. Collection of Akiko Yamazaki and Jerry Yang.

Why do you think it’s so important to use culture to encourage this dialogue between Asia and the West right now? How do you see this relationship and avenue of cultural exchange evolving?

That’s the question that we want to ask, and clearly the answer will be informed by geopolitics, including the rise of China and the tensions on the Korean peninsula. People forget how connected China, Korea, and Japan have been through the centuries and how their arts are really related. But the thing is, people don’t really need to be pushed to have this conversation—as soon as you raise the topic people start a dialogue, because there’s so much to talk about.

Do you have any theory as to why other people who have attained great success in the tech industry have been slow to embrace art?

I don’t know if I agree with that narrative. It’s certainly the case that many of them do collect art, though they may not be as public about it. There are now galleries in Palo Alto emerging, and certainly in San Francisco there’s much more of a scene. Even on the board of San Francisco’s Asian Art Museum, there are more new people from Silicon Valley than there are from San Francisco, and they’re joining not for social reasons, but really from their appreciation for the art. Many of them are collectors.

So it’s emerging—maybe that’s the best way to think about it. And certainly if you look around the world, in Japan there are tech entrepreneurs I know who are collectors, and in China for sure they’re all collectors. It’s just that people here in the Valley are doing more it quietly, and maybe as time goes on and their collections become more mature and they’re ready to share.

There is definitely a commercial and practical element to of all this as well. Art is a great thing to appreciate, and if you can buy it low and hold onto it, it can be worth a lot of money down the line. This is no different for people in the Valley than it is for financiers.

Also, while collecting art used to be about access and who you know, I think that’s really changing. Akiko and I look for art and deal with artists worldwide, often in Asia, but we don’t fly to Asia every week to see stuff—we’re really relying on modern technology to help us figure things out. It’s come a long way since I started collecting 20 years ago. It’s amazing how much information is available online, and how fluid things have become. I’m sure the business model of the art world will change over time, too. It’s still an old-boys-and-old-girls network, and that part is charming in some ways, but it’s definitely evolving.

Liu Guosong‘s Zen Dream, 1966. Ink and light color on paper. Collection of Akiko Yamazaki and Jerry Yang.

You’re an investor today through Ame Cloud Ventures, where you focus on emergent technologies. Do you ever consider getting involved in the art-and-tech intersection?

Not really. I know there are a couple of artist-driven marketplaces like Patreon, but we have not invested in those. Partly this is because we like things that are heavy in tech, because we invest in very early-stage companies, so we want them to have a solid technology background, and generally this kind of art/tech sector has been more art and less tech. It’s just something that I think will come with time.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.