Art World

Yayoi Kusama’s Simple Forms Hide Complex Realities—Here Are Three Facts You May Not Know About Her Widely Admired Work

Kusama uses uncomplicated shapes and colors to build bridges between audiences.

Kusama uses uncomplicated shapes and colors to build bridges between audiences.

Maria Vogel

In these turbulent times, creativity and empathy are more necessary than ever to bridge divides and find solutions. Artnet News’s Art and Empathy Project is an ongoing investigation into how the art world can help enhance emotional intelligence, drawing insights and inspiration from creatives, thought leaders, and great works of art.

Yayoi Kusama is a household name, and an artist like no other. Her life story, which involves intense mental and emotional turmoil, is also one of perseverance: at the age of 91, she continues to make path-breaking work and win audiences the world over.

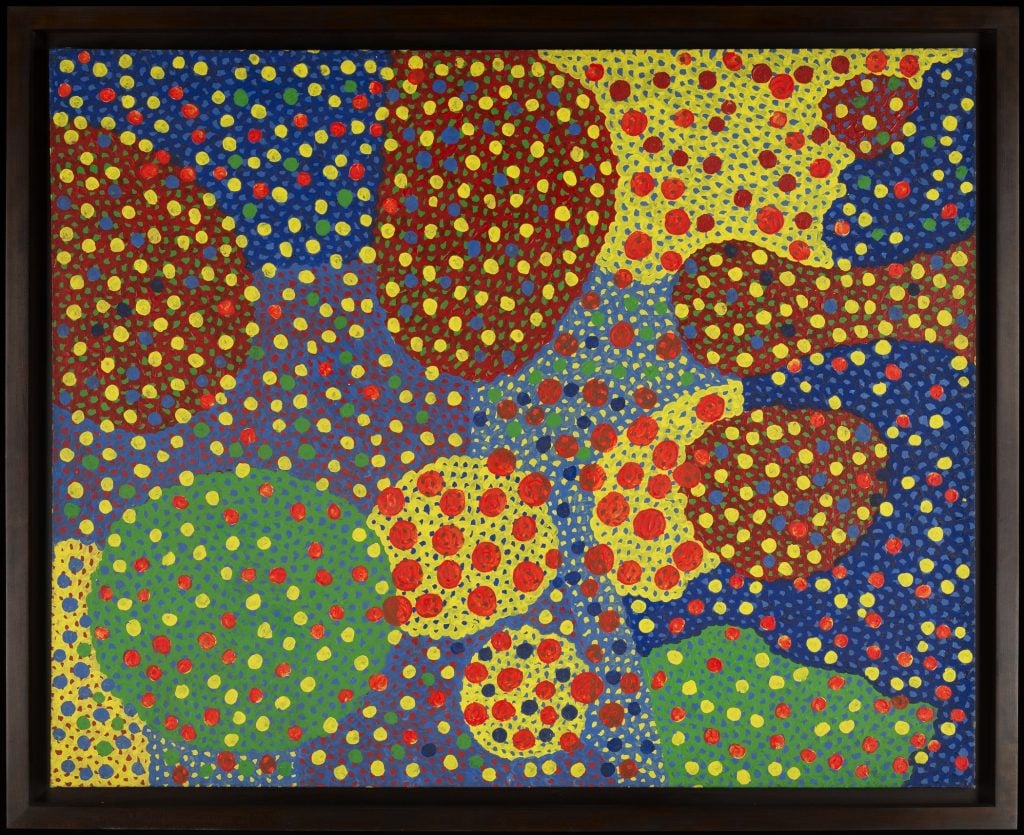

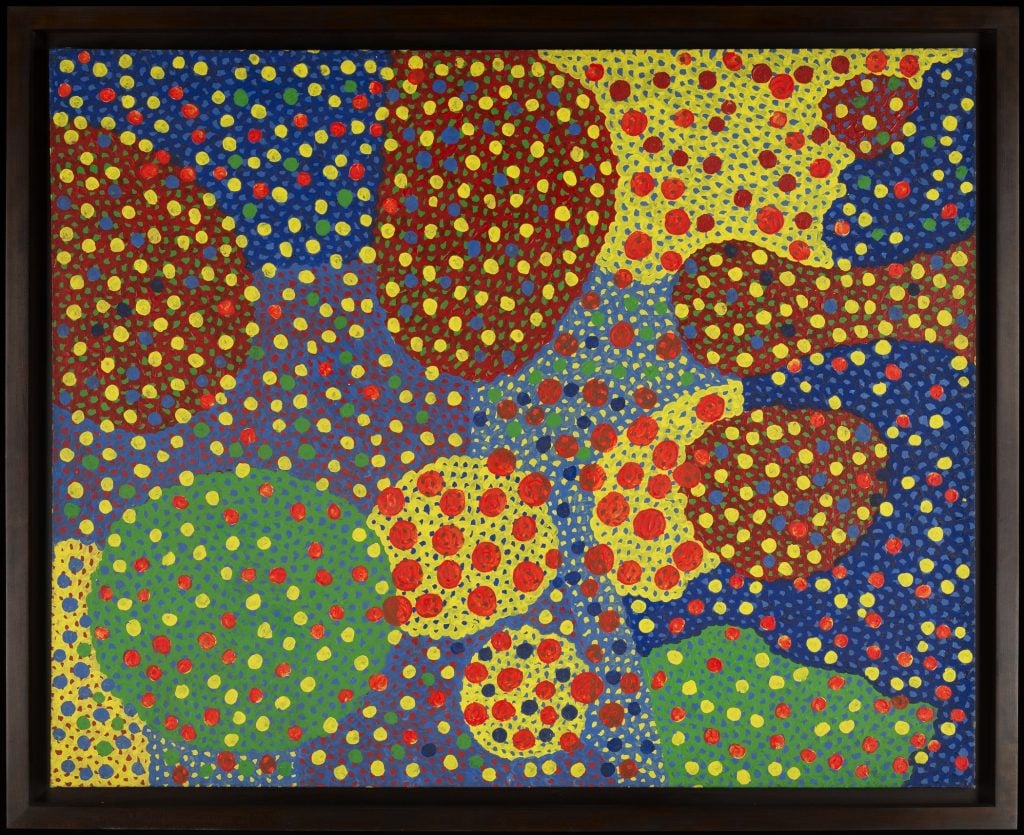

Through the heartfelt emotion that she imbues into every work, Kusama provides a shared language that transcends boundaries. Part of her appeal is her honesty and bravery, and her vocal discussion of the lifelong struggles she has faced. Untitled, a work from 1967 that belongs in the collection of the Minneapolis Institute of Art, in particular is a sterling example of how her work encourages empathy.

We worked with Karleen Gardner, the director of the Minneapolis Institute of Art’s Center for Empathy and the Visual Arts, to get a deeper sense of the work’s meaning, history, and its connection to emotional intelligence.

A woman looks at the art of Yayoi Kusama at the David Zwirner Gallery in New York. Photo: TIMOTHY A. CLARY/AFP via Getty Images.

Like many of Kusama’s most famous works, Untitled features shapes and forms that appear repeatedly across the entire surface. Working in this way is a type of meditation for Kusama, but it also projects a meditative state onto the viewer, who can easily become entranced with the patterns of primary colors and dots.

This abstract motif, which Kusama calls an “infinity net,” is one that the artist would use over and over again in many works throughout her decades-spanning career. Through her use of repetition, Kusama asks the viewer to look closer at the work to see what is actually occurring. She creates an experience that beckons you in, and leaves you in visual contemplation.

A boy in Yayoi Kusama’s “obliteration room” at Auckland Art Galley. Photo by Hannah Peters/Getty Images.

In Untitled, Kusama forms a visual vocabulary that is, at its core, quite simple. The ways in which it is employed, however, is unmistakably unique. By creating artworks from familiar, simple forms, she suggests childhood naiveté, drawing viewers into a complex web of associations, emotions, and memories. Looking at the work, it’s as if you experience something for the first time, all over again.

With her work, Kusama broadens the scope of her audience, which explains, in part, why she appeals to so many people who are outside the art world, strictly speaking. Even in the wake of widespread critical—meaning, insider— success, Kusama has continued to explore these themes and forms, building a language that practically anyone can identify with.

Yayoi Kusama at the National Art Center in Tokyo in 2017. Photo: TOSHIFUMI KITAMURA/AFP via Getty Images.

All of Kusama’s principles, and the way her work builds bridges between audiences, is connected with her lifelong struggle with mental illness.

Since early childhood, Kusama has suffered from hallucinations, in some of them even imaging forms that make it into her work. In addition to these traumatic episodes, she also dealt, as a child, with a chaotic home in which she was physically abused. Her artistic practice became an escape from those struggles.

Working in the styles she did, Kusama was able to take momentary breaks from a world that felt cruel and unfair. Despite regular hospitalizations from overwork, suicide attempts, and various diagnoses (such as schizophrenia and obsessive-compulsive disorder), art has remained Kusama’s medicine to this day. It is the channel in which she heals, and which allows viewers into her world to broaden their understanding, and expand their emotional intelligence.