Art & Exhibitions

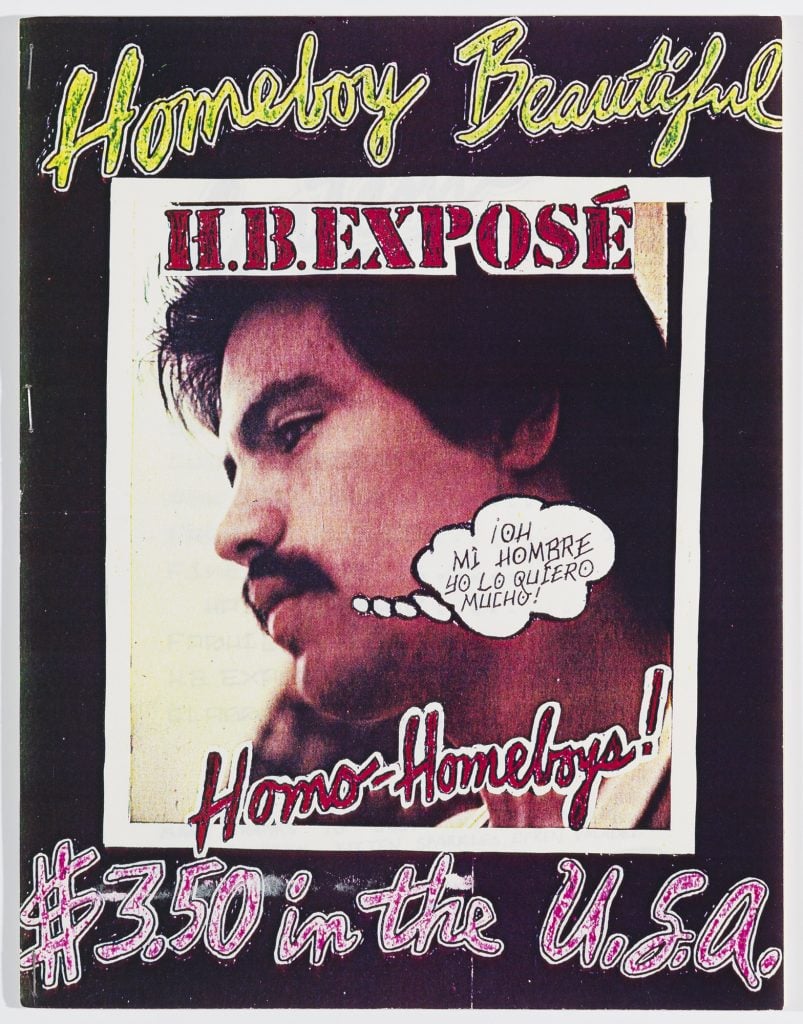

More Than 800 Zines Created by Artists From Raymond Pettibon to Miranda July Are Going on View in a Major Museum Show

"Copy Machine Manifesto" at the Brooklyn Museum brings together artist zines from the past 50 years.

"Copy Machine Manifesto" at the Brooklyn Museum brings together artist zines from the past 50 years.

Min Chen

In the 1970s, the fanzine scene exploded. These unofficial, DIY publications may have emerged as early as 1930 in the science fiction space, but it was with the accessibility of production techniques, namely the photocopier, that led them to become the subculture medium of choice. Zines about punk, feminism, street culture and conceptual art abound—their Xeroxed pages crammed with appropriated images and typewritten text—created by fans, amateurs, and often, too, by artists.

In its first major exhibition on the subject, the Brooklyn Museum will bring together a feast of fanzines made by artists from Canada, Mexico and the United States over the past century. More than 800 publications by nearly 100 artists are on view at “Copy Machine Manifesto: Artists Who Make Zines,” which will chart the timeline of zine-making, while attempting to position the artist zine within contemporary art history.

“We’re trying to show the central role of zine production in contemporary art by looking at zines in relation to painting, photography, filmmaking, video performance, all these other mediums that they went hand in hand with in terms of production,” said Drew Sawyer, the exhibition’s co-curator, over Zoom.

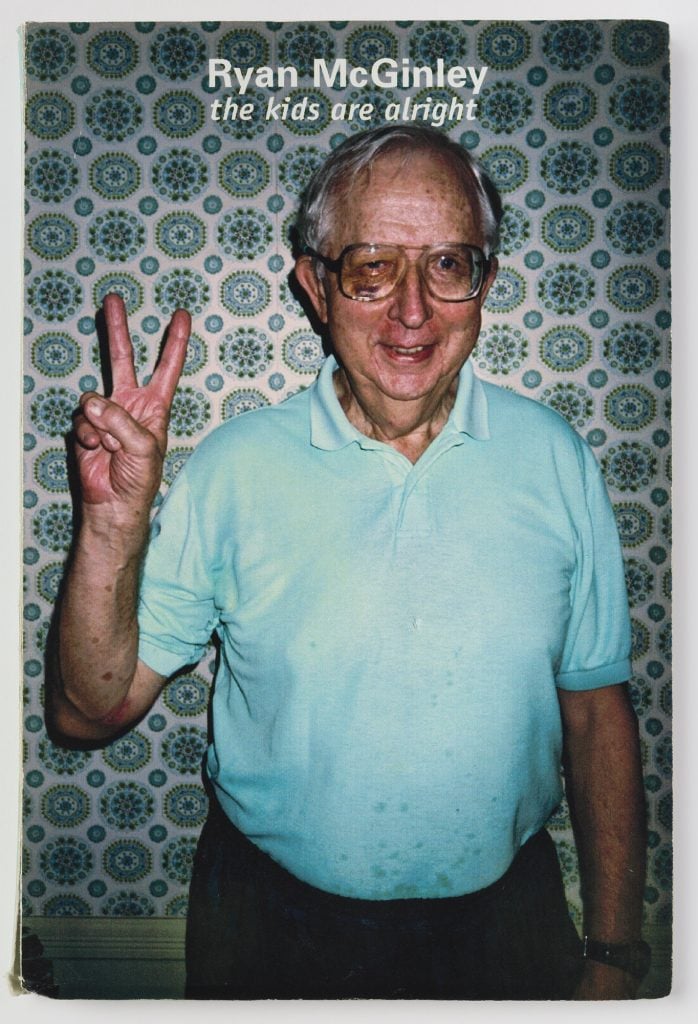

Bruce LaBruce, J.D.s, no. 8 (1991) (detail). Collection Bruce LaBruce. Photo: David Vu.

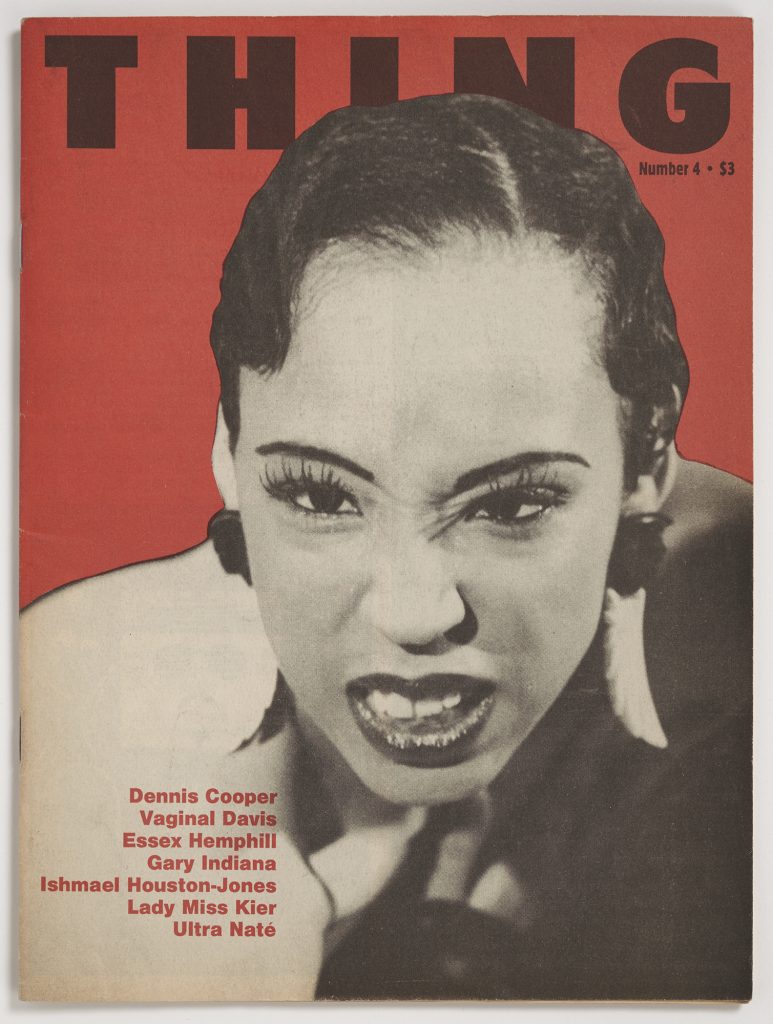

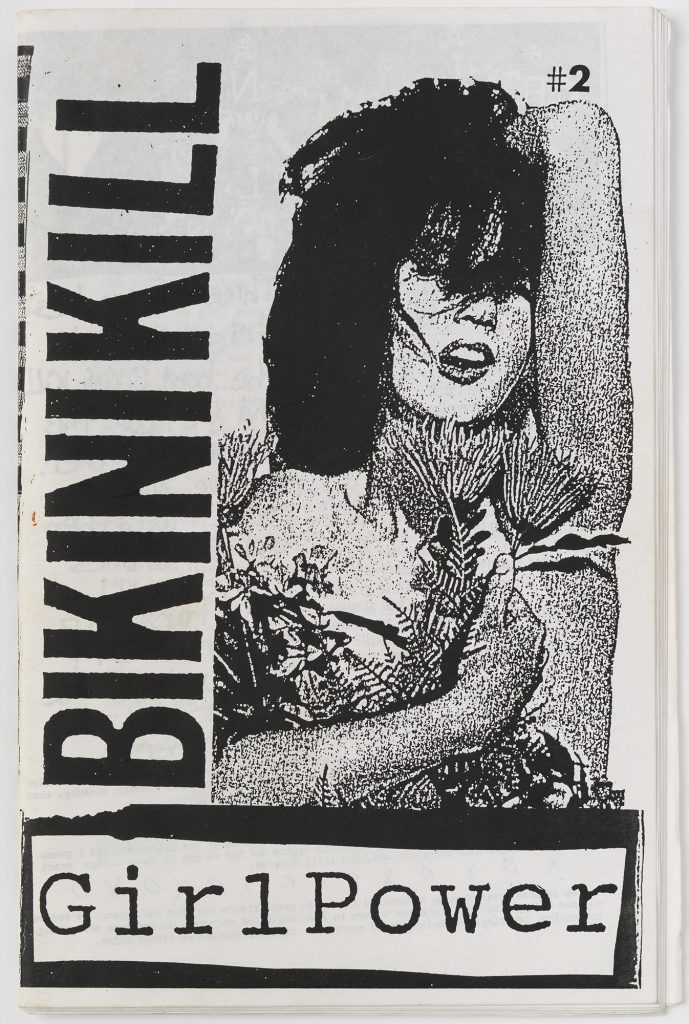

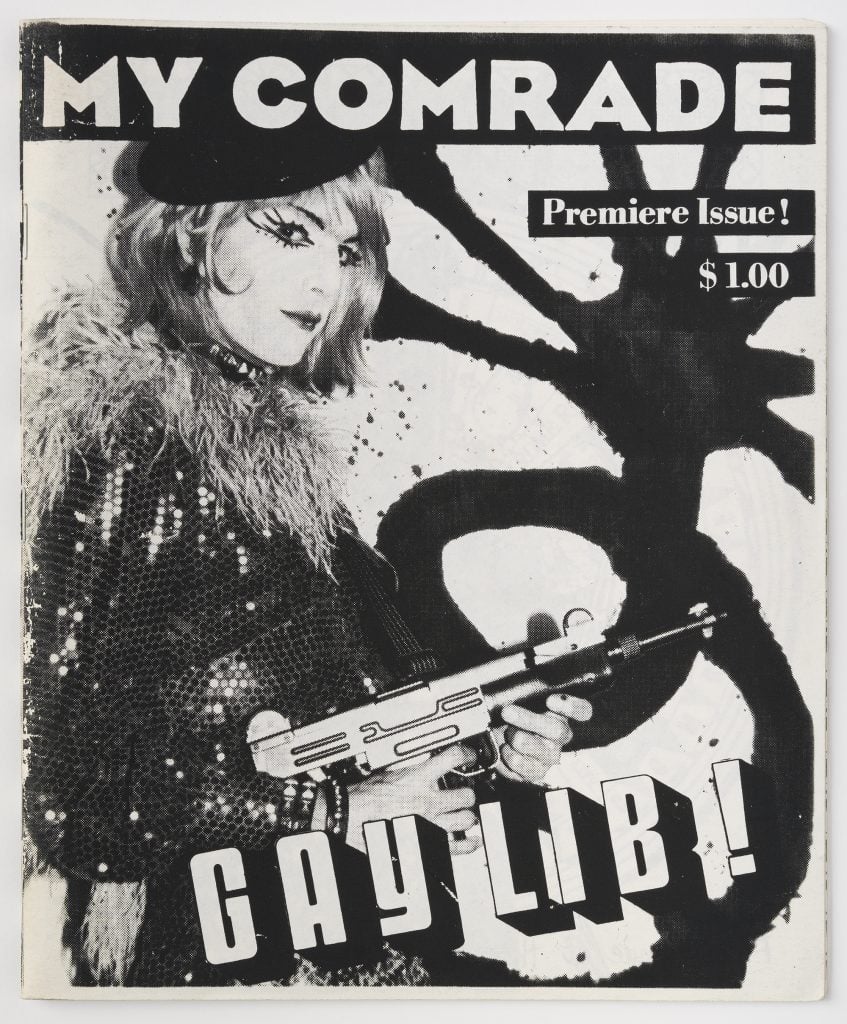

The show is organized chronologically and centers on the communities that zines cultivated. The punk years between 1975 and 1990 are detailed with zines by Raymond Pettibon, Lisa Baumgartner, Bruce LaBruce, and David Wojnarowicz, which helped shape the look and iconography of the genre. Meanwhile, the feminist and queer undergrounds of the nineties are captured in publications produced by Vaginal Davis, Johanna Fateman, Ho Tam, and Kathleen Hanna.

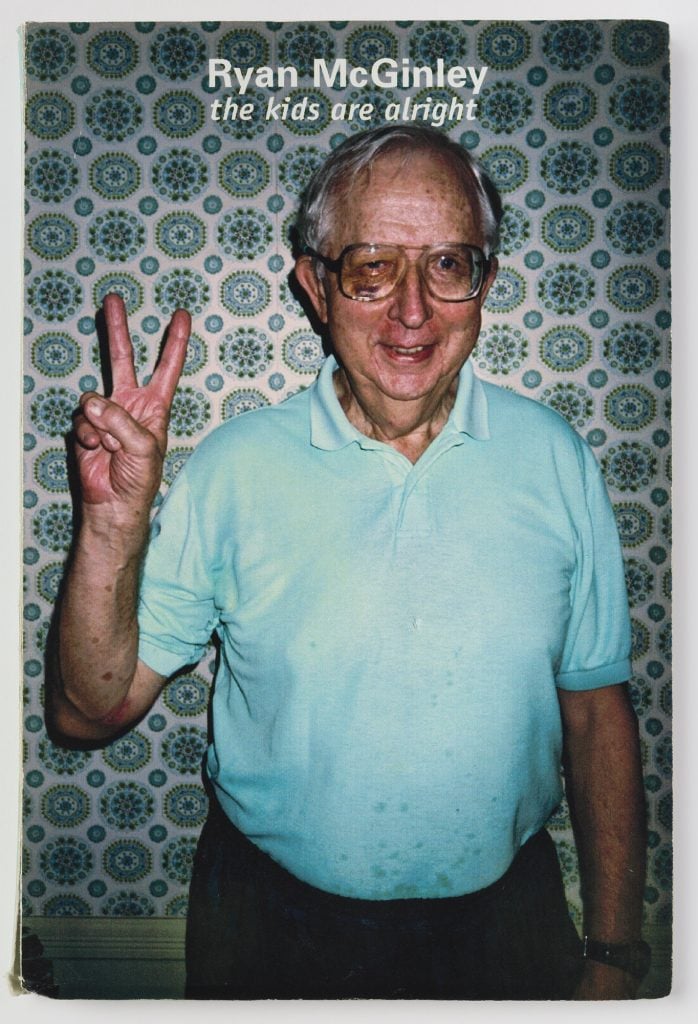

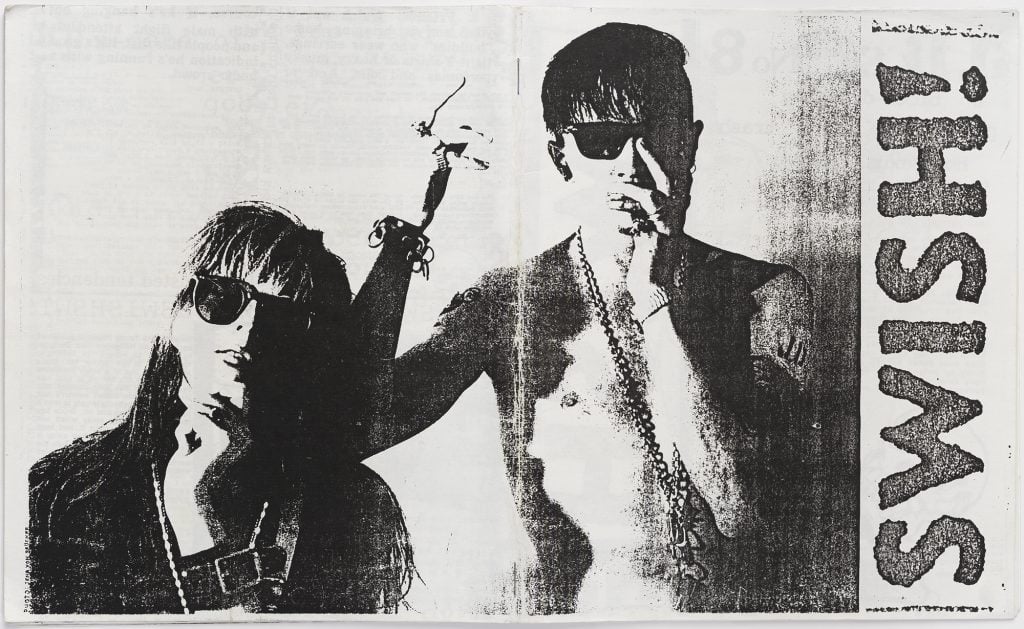

The fanzines are further accompanied by works of art, linking the publications to the artists’ broader practice. For example, the first issue of Joey Terrill’s HomeboyBeautiful zine from 1978, compiling his photo novellas and comic strips, will be shown alongside Breaking Up / Breaking Down, his early eighties canvas that was painted in a similarly multi-paneled storytelling format.

Joey Terrill, HomeboyBeautiful, no. 1 (1978). Photo: ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

Zines, being objects that are created in small batches and circulated in underground or informal networks, are not made for a long shelf life, which made sourcing for the exhibition quite the challenge for organizers. While a number of zines have been collected in libraries and archives (New York University’s Riot Grrrl Collection, for example), the curators recall a years-long process of locating artists and raiding personal collections to locate copies.

“Our archive research included me and Drew literally on our knees, in storage spaces, rifling through stuff that people hadn’t looked at in a long time,” said co-curator Branden W. Joseph. “There were artists who had just one copy left. The ephemeral nature of the zine is really shown in the archives.”

They also made sure to acquire permissions from artists to include their zines in the show. These publications, after all, have often been created with an anti-establishment stance that thumbed its nose at media hierarchies. Some artists refused, but most agreed.

“I think they felt like even if they made the zine decades years ago with a sort of anti-institutional motivation, they also recognize the importance of what was produced and the need to preserve those histories, which have largely gone underwritten until now,” said Sawyer.

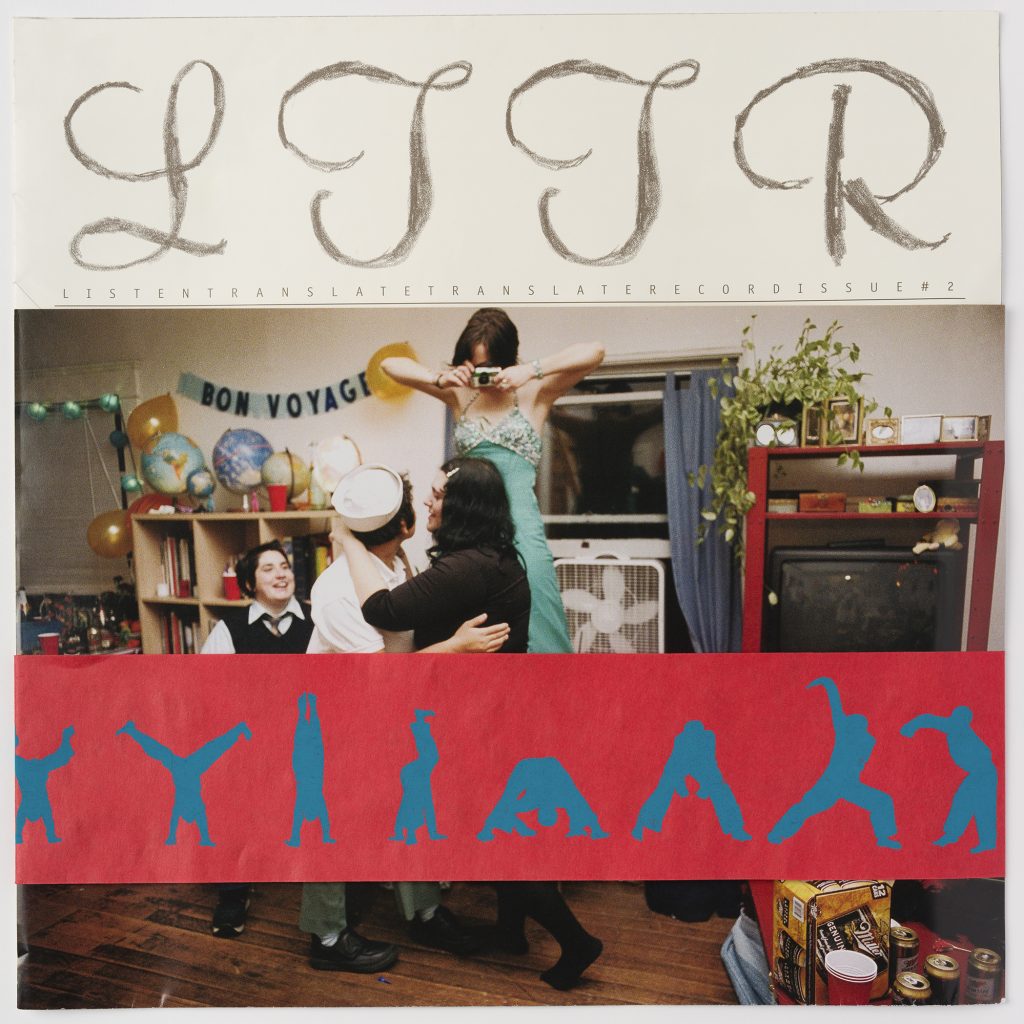

LTTR (Ginger Brooks Takahashi, K8 Hardy, Every Ocean Hughes, Ulrike Müller), LTTR, no. 2, “Listen Translate Translate Record” (2003). Collection Philip Aarons and Shelley Fox Aarons, Photo: David Vu.

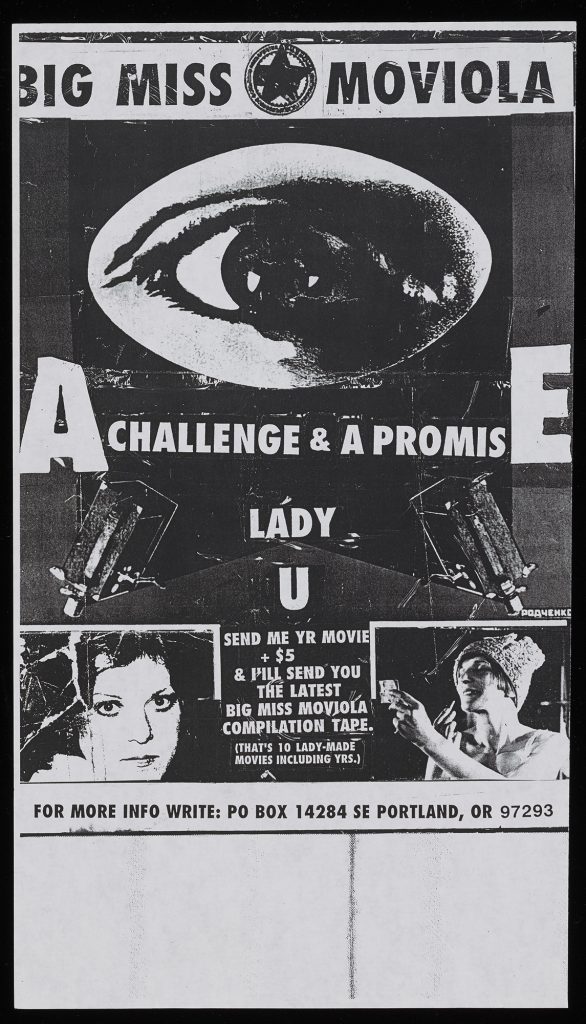

But far from being historical artifacts, zines continue to hold resonance for artists today. If the continued presence of fanzine fairs isn’t convincing enough, the exhibition presents publications by Terence Koh, queer collective LTTR, and Miranda July, which foreground the medium’s continued resonance for creators outside the dominant culture. The curators argue that, despite (or in tandem with) a digitized age, there remains a tactile, accessible appeal to the zine.

“One thing that zines have always represented is a certain type of intimacy—of distribution, of self-revelation, of reception. There’s a certain physical relationship,” said Joseph. “I think that’s one of the things that continues now.”

See more zines from the show below.

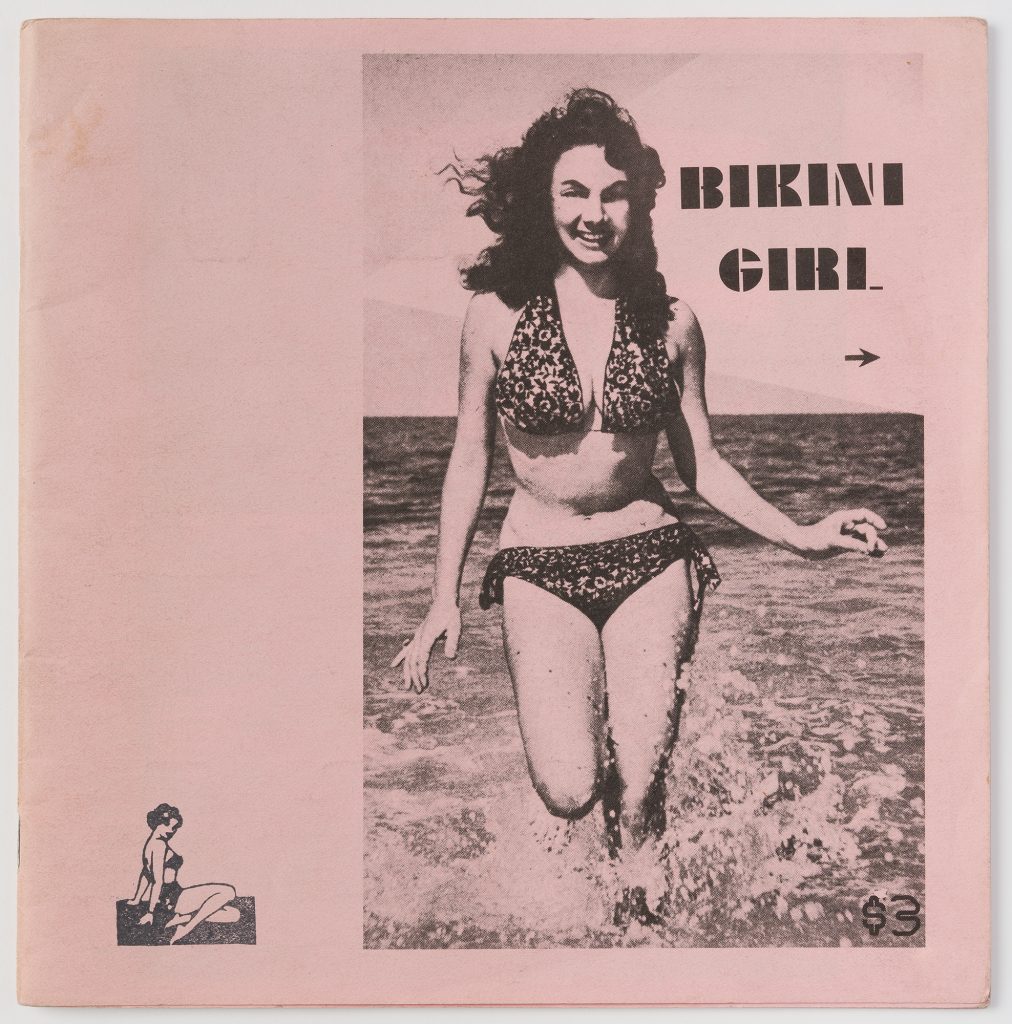

Lisa Baumgardner, Bikini Girl, vol. 1. no. 5 (1980). Collection Philip Aarons and Shelley Fox Aarons. Photo: David Vu.

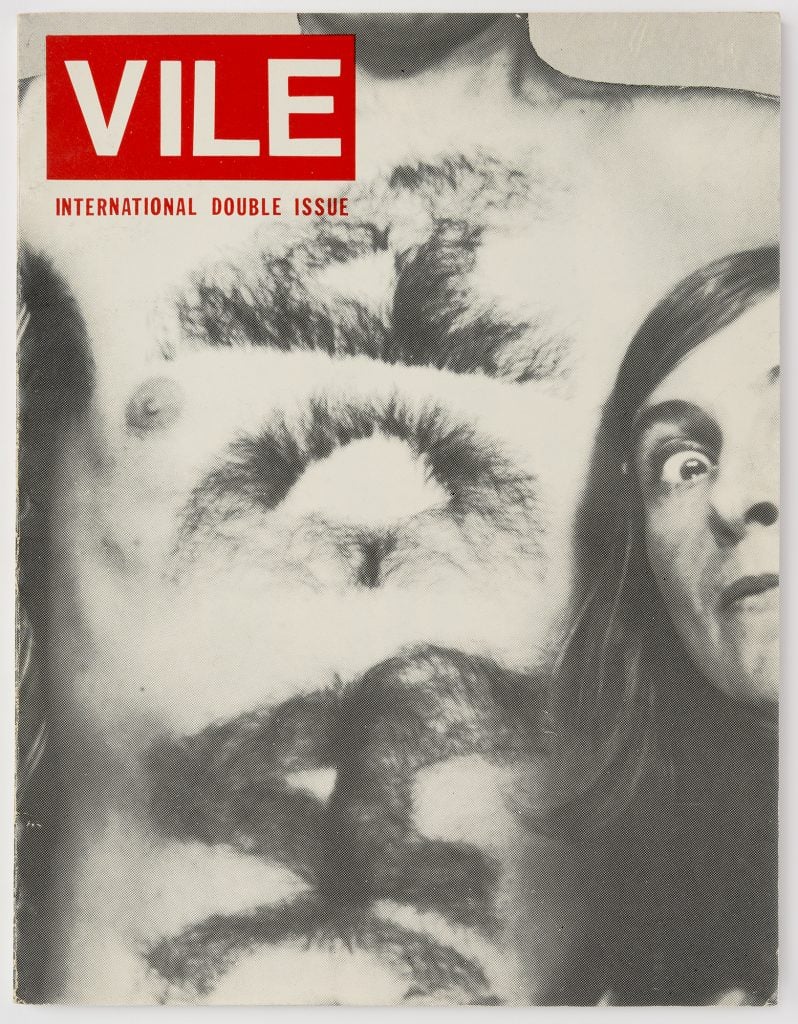

Anna Banana, Vile, vol. 1, no. 2 / vol. 2, no. 1 (issue 4) (1976). Collection Philip Aarons and Shelley Fox Aarons. Photo: David Vu.

Pat McCarthy, Still from Babylon Pigeons, no. 13, “Photocopying Pigeons” (2019). Collection the artist.

Robert Ford, Thing, no. 4 (1991). Collection Steve Lafreniere. Photo: Brooklyn Museum, Evan McKnight.

Kathleen Hanna with Billy Karren, Tobi Vail, Kathi Wilcox, Bikini Kill, no. 2 (1991). Collection Philip Aarons and Shelley Fox Aarons. Photo: David Vu.

Miranda July, Big Miss Moviola Chainletter #2: Directory (The Underwater Chainletter) (1996). Photo: Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2016.M.20)

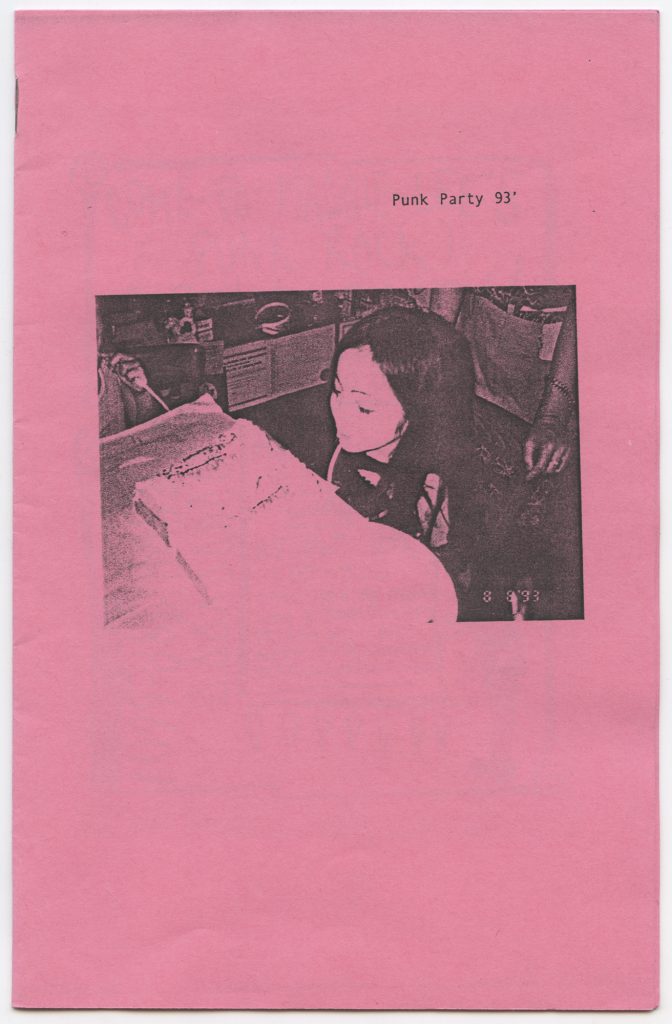

Maggie Lee, Punk Party 93′ (2020). Collection the artist.

Linda Simpson (a.k.a. Les Simpson), My Comrade, no. 1 (1987). Collection Steve Lafreniere, courtesy Arthur Fournier. Photo: Brooklyn Museum, Evan McKnight.

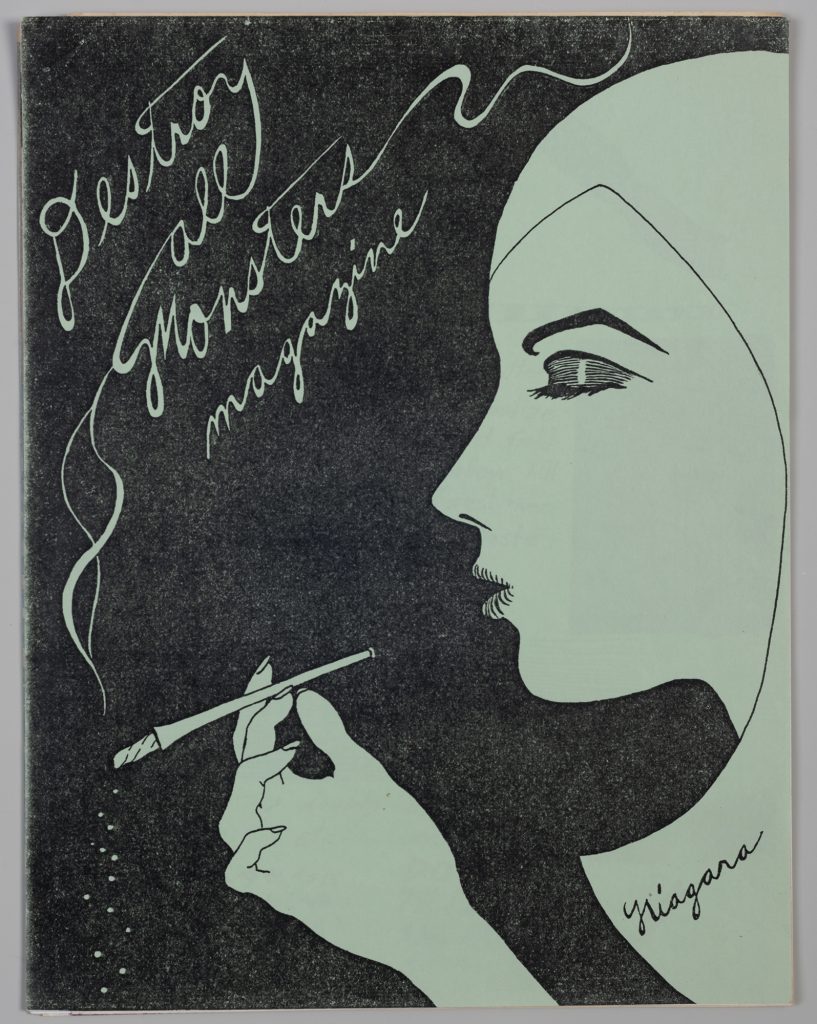

Cary Loren, Destroy All Monsters Magazine, no. 1 (1976). Collection Cary Loren. Photo: Brooklyn Museum, Jonathan Dorado.

“Copy Machine Manifestos: Artists Who Make Zines” will be on view at the Brooklyn Museum, 200 Eastern Parkway, Brooklyn, New York, November 17, 2023 through March 31, 2024.