Galleries

David Zwirner Hires Team of Docents to Combat Epidemic of Gallery Selfies

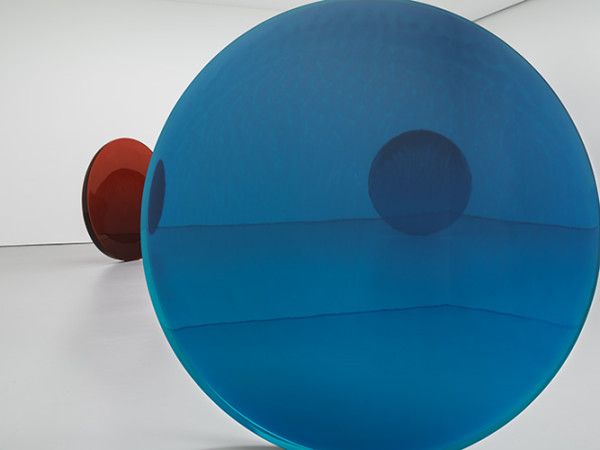

The sculptures exert a powerful pull—but don't get too close.

Photo Daniel Pillis.

The sculptures exert a powerful pull—but don't get too close.

Brian Boucher

“It’s the biggest selfie-generating show I’ve ever seen,” said docent Alexa West, standing at New York’s David Zwirner Gallery on Tuesday afternoon, in a show devoted to reflective works by De Wain Valentine (b. 1936).

Zwirner has taken the rare step for a commercial gallery of stationing docents at its 19th Street venue; they talk to visitors about the exhibition while reminding them not to touch the fragile works or to draw too near as they explore the show’s selfie potential.

“People want to get as close as possible, so we’re part informational, part security,” said a bespectacled Daniel Pillis, an MFA candidate at Carnegie Mellon who was sporting a necktie.

West is an art student at Cooper Union. They’re hardly the proper elderly women you might think of when you hear the word “docent.”

Installation view, “De Wain Valentine: Works from the 1960s and 1970s,” David Zwirner, New York, 2015. © 2015 De Wain Valentine/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Zwirner has mounted a lot of highly photogenic shows that have spawned thousands of visitor self-portraits—two exhibitions by Yayoi Kusama in the last two years, and, in 2014, Jordan Wolfson’s show featuring an animatronic dancer in front of a mirror, the ultimate provocation to get out your iPhone.

The Valentine show includes nearly two dozen sculptures by the Colorado-born California Light and Space artist, made in a polyester resin that the artist developed himself. Existing varieties of resin couldn’t be cast at more than 50 pounds, as they were prone to cracking. Working with a scientist, Valentine developed a more durable brand that’s now known as Valentine MasKast Resin.

Installation view, “De Wain Valentine: Works from the 1960s and 1970s,” David Zwirner, New York, 2015. © 2015 De Wain Valentine/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Perhaps the centerpiece of the show is Two Gray Columns (1975–76), a pair of nearly 12-foot-high walls, seven feet wide, that taper from about 10 inches thick at the bottom, narrowing as they ascend.

“Everyone wants to get a shot of themselves from the far side, standing between the two,” Pillis said, gesturing toward the few inches between the sculpture’s two parts.

This is the first time the work is being shown as intended. It was commissioned for the Illinois offices of a pharmaceutical company, but was orphaned when the design of the space was altered at the last minute and became too small to accommodate them. Valentine tried showing the two parts on their sides but wasn’t satisfied with the result.

Installation view, “De Wain Valentine: Works from the 1960s and 1970s,” David Zwirner, New York, 2015. © 2015 De Wain Valentine/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Other, smaller columns are exhibited a foot or two from the walls, and visitors are dying to get a picture of themselves standing behind the works, Pillis said. That’s not allowed. Anyway, when I studied the five-foot-tall Column Flourescent Yellow (1968) close up, my impulse was more to get inside of it. “It sucks you in,” Pillis agreed.

Valentine told the press during a June gallery talk (supplied to artnet News on video) that “these pieces grew out of when I came to California and fell in love with the sky and the ocean. They were like big pieces of atmosphere. I always wanted to have a magic solid so I could cut out a big piece of sky or a big piece of ocean.”

De Wain Valentine studio, Venice, California, 1968. © De Wain Valentine/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, 2015; courtesy of David Zwirner, New York/London.

Photo: De Wain Valentine

Several impressive, perfectly disc-shaped sculptures in blue, red, and gold mysteriously stand on their own, without any support. One, Circle Blue Smoke Flow (1970), distinctively features color variations that resemble wisps of smoke that refer, the artist has said, to L.A. smog.

The Zwirner outing is Valentine’s first New York solo since 1981. “Galleries will never show art made of plastic,” Valentine was told in the ‘60s, when he started showing dealers photographs of his work.

Valentine has gained renewed attention in recent years, following his inclusion in the Getty Center’s Pacific Standard Time exhibitions, especially a solo devoted to the 1975–76 work Gray Column. That work had never before been on public view. The 1970 sculpture Red Concave Circle was recently donated to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art by Bank of America.

“Richard Serra more aggressively reshaped our experience of space,” said Pillis, referring to Valentine’s contemporary, the subject of a show at Zwirner’s 20th Street gallery, one block north. “The Light and Space artists treated space more as a found object.”

For those who can’t resist their inclinations to a tactile experience of art, visitors are allowed to touch the Serra works, Pillis pointed out.

The docent job is an excellent gig, he and West agreed. “Visitors ask questions, and that leads to more questions, and then you’re in a conversation,” West said.

“It’s great to get to point out how cool the work is,” Pillis said. “And, to let them know not to get too close.”