Art & Exhibitions

11 Uneasy Questions Raised by Manifesta 11

Where is the art? Who is it for? And can there be too many masturbation paintings?

Where is the art? Who is it for? And can there be too many masturbation paintings?

Hettie Judah

Evgeny Antufiev’s joint venture with pastor Martin Rüsch at the Wasserkirche. Courtesy of Manifesta 11, ©Wolfgang Traeger

For its 11th edition, Europe’s nomadic biennial finds itself in Zürich as the city celebrates the centenary of Dada. Under the direction of artist Christian Jankowski, “What People Do For Money” is a dense, complex, and ambitious venture that seeps deep into the fabric of its host city. With a commissioning and exhibiting system based on joint enterprise, and a theme exploring labor and remuneration, it is also a biennial mesmerised by its own processes. Manifesta 11 is less an exhibition of individual star turns than a dense mesh of related gestures that together generate questions and complications surrounding the relationship between art and the world it occupies.

1. Where does life stop and art begin?

Manifesta 11 matched 30 artists to Zürich professionals of their choice, from pastor to prostitute, policewoman to Paralympian. Artworks were, theoretically, the product of interaction between artist and host, and exhibited both at the main biennial sites and at a satellite venue. While some of these joint ventures resulted in a clearly delineated “work”—such as Santiago Sierra’s Protected Building, for which a security specialist helped the artist barricade the biennial’s Helmhaus venue as if it were under threat—in many cases it is unclear where the interaction with the host ends and the work begins. Evgeny Antufiev’s Eternal Garden entailed extensive correspondence with the pastor of the Wasserkirche. The result is a sprawl of artifacts, exchanged ideas and made objects: a work without boundaries that becomes an archive of its own avid production.

2. Who is the art for?

As in Antufiev’s case, intense encounters between artist and host can result in works that feel excluding rather than involving. Jiří Thýn’s collaboration with a clinical pathologist resulted in a series of cut-up magazine photographs exchanged by the pair during correspondence, photographs by Thýn of her working spaces, and a series of text works applied to the windows of her hospital’s atrium in coloured vinyl. The text is in English, suggesting that it is directed neither at the hospital’s workers, nor its Swiss visitors, but is in fact an extension of the relationship between artist and host.

Mike Bouchet, Zurich Load . Courtesy of Manifesta 11, ©Camilo Brau

3. How does it feel to have your work shown next to 80,000 kilos of poo?

For The Zürich Load Mike Bouchet collaborated with the city’s sewage works, and by extension, with its entire population, forming a single day’s load of human waste into a room full of vast dried dung blocks. Shown at the Löwenbräukunst, in a gallery with a heavy, well-sealed door, the work is rounded off with a turdy fragrance so emetic that few visitors last longer than they can hold their breath. That, however, is just long enough to notice that there are other works on show in the same gallery. Which unfortunate artist(s) had their work stationed next to The Zürich Load? We have yet to encounter anyone who got close enough to find out.

4. What’s the deal with satellite venues?

Expected to show work both at a satellite venue and in Manifesta’s group exhibitions, some artists presented two editions of the same work, some sibling works, and others—notably John Kessler—research materials at one venue (the Helmhaus) and the work itself at the other (a cuckoo clock-inspired automaton displayed in a watchmaker’s shop). Context had a transformative effect. Jon Rafman’s Open Heart Warrior read as mere sinister play amid the sensory overload of the group show. Generic virtual landscapes played on three screens, while grotesque and disturbing images from violent computer games bled in and out of the picture, often in the viewer’s peripheral vision. Mood music and voice-overs played on a surround sound system, twisting the language of meditation tapes to negative vibe. Viewed in small cage at a floatation centre, Open Heart Warrior became a disquieting suggestion of the psychic impact of omnipresent violent imagery and belligerent narrative in film and gaming culture.

Marco Schmitt, still from Exterminating Badges 2016. Courtesy of Manifesta 11

5. Can artists and civilians ever just be friends or does someone always end up getting screwed?

Some hosts seemed to enjoy their encounter with the art world—the police amateur dramatics in Marco Schmitt’s voodoo police fantasia Xterminating Badges in particular looked fun—though it was less easy to see what the artist got out of the process. In other cases, the relationship between artist and public provoked moral queasiness. In perhaps the most uneasy and lingering work of the biennial, Leigh Ledare filmed 21 Zürichers engaged in an intense three-day group therapy process. Over dozens of hours of footage, participants confess, confront, argue, bully, and weep while Ledare sits at the side of the room taking notes responding to his own position as observer.

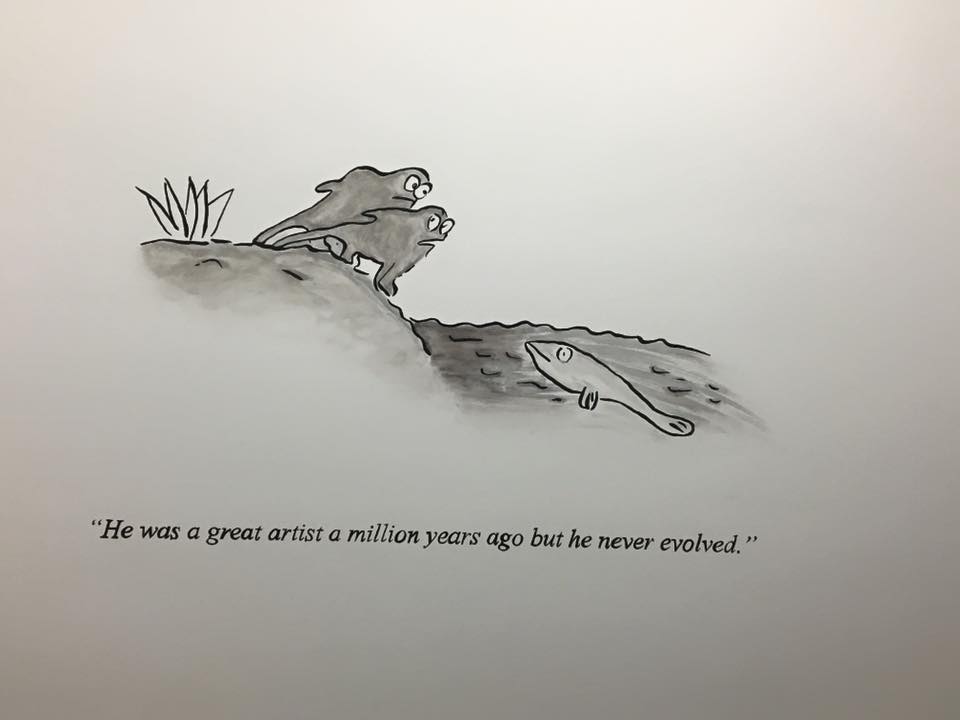

Pablo Helguera’s “Artoons” for Manifesta 11. Photo courtesy of Hili Perlson.

6. Who forgot to check their privilege?

Over the opening weekend, Pablo Helguera delivered a performance lectures on inequity in the art world at which participants played the “Dictator Game” and Helguera sung ballads of labor and protest by Woody Guthrie, Joe Hill, and Óscar Chávez. His rousing speech questioned the relevance of art to most people’s lives, and how the rituals and structures of the art world serve to isolate it still further. Helguera’s words led one to ponder how the prosperity of Zürich as a locale had perhaps skewered the participating artist’s sense of relative privilege when dealing with their professional hosts.

Andrea Éva Gyoeri. Courtesy of Manifesta11 ©Wolfgang Traeger

7. Is there such a thing as too many pictures of women masturbating?

Andrea Éva Györi’s energetic watercolour paintings of women masturbating, their fantasies while doing so, and the details of their arousal or lack thereof were optimistic and charming when discreetly displayed at an upmarket lingerie store. At the Löwenbräukunst they fill almost an entire wall of the building, ceiling to floor, leading some visitors to quail at such a quantity of flesh and fingering. Now that we’re dealing with a generation facing sexting, increased instances of coercion, and the side-effects of omnipresent online porn, the spectacle of women understanding and taking control of their own sexuality seems every bit as urgent as it was when Tee Corine published The Cunt Colouring Book (1975). Too many? No way.

8. What do Swiss curators do at 6.30am?

Move over Hans Ulrich Obrist and the Brutally Early Club: throughout Manifesta, Adrian Notz the director of Cabaret Voltaire is opening each day with a Dada officium. On a rainy morning in June, he recited an essay by Man Ray in which Dada and its adherents were peddled in the language of a soap powder advertisement.

9. What does the job of “artist” entail?

As per Man Ray, the artist’s role has long entailed a degree of self-promotion. Georgia Sagri questioned what could and should be expected of her in her role as “artist” when approached by Manifesta to participate in their documentary project. First she proposed billing the biennial by the hour as an actress for the filming. Then, that if she were not being hired as a performer, but filmed as an artist, she be afforded complete creative control of the process. Sagri presented this correspondence and a related film as part of the parallel program, and in a performance lecture alongside her work Documentary of Behavioural Currencies.

John Kessler for Manifesta 11. Courtesy of Manifesta 11 ©Wolfgang Traeger

10. What do people do for no money?

Sagri also questioned the idea that a profession had primacy in bestowing identity over the aspects of life that are done for no money. Such as, for example: mothering, caring, making art, or volunteering to work at a biennial. The question of remuneration is a pointed topic for all of us working in the creative arts (or, as we are now known, “content providers”) though not one widely explored in the commissions.

11. How many Matadors are there in Zürich?

A professions-themed film program offers special tickets to each screening according to the job portrayed in the movie. At a guess, I was a Swiss Banker (2007), Taxi Driver (1976), and The Station Agent (2003) will all be well subscribed. The Great Dictator (1940) and Matador (1986)? Perhaps less so.