On View

William Powhida’s First Gallery Show in Years Is Taking Aim at Problematic Art World Patrons—and It Turns Out All Of Us Are Complicit

His latest works offer a broad indictment of the art world.

His latest works offer a broad indictment of the art world.

Caroline Goldstein

It’s not often you come across an artist who tells you who they won’t sell their work to, but that’s exactly what William Powhida does in the introduction to his first solo gallery show at Postmasters Gallery in almost five years.

The press release for “Complicities,” open now through October at the Tribeca-based gallery, reads frankly: “William Powhida has no illusions that this work will change the systems he inhabits, or save anyone, but he will not be selling any of this work to any of the subjects depicted (sorry, Glenn Fuhrman!).”

The show features intricate, large-scale diagrams that map out the links between (mostly) powerful men like Warren Kanders and Mortimer Sackler, their businesses and foundations, and the arts institutions they fund. The data is culled from reams of reports and business statements that have come under public scrutiny in recent months, as more and more scandals play out in the news. The artworks have footnotes with sources.

This gamble of an exhibition shows off Powhida’s draughtsmanship and graphic sense—the hyper-detailed drawings have taken months to laboriously create—infused with a sober institutional critique and irascible commentary. It lends his art’s style to monumentalizing the recent wave of scandals that have rocked the art world over patronage and politics.

During the recent protests over the presence of Warren Kanders, a weapons and teargas manufacturer, on the board of the Whitney, Powhida was part of a group called the (De)Institutional Research Team, or (D)IRT, which infiltrated the Whitney Biennial with an alternative visitor’s guide that outlined criticisms of Kanders and the museum.

At Postmasters, the drawing Powhida made about Kanders and his tangled web of similarly well-heeled tycoons is laid out in a flow chart, complete with watercolor portraits of Kanders alongside other art-world heavyweights connected to him and his enterprises through various social pathways.

William Powhida, Safariland (Direct Investment) (2019). Courtesy of the artist and Postmasters Gallery.

This makes the drawing personal, in a way. Powhida explained that some of those named in the Kanders drawing, including John C. Phelan and Glenn R. Fuhrman, are people he’s had professional relationships with in the past through sales of his work. “I was surprised to find them on the same board as Warren Kanders, and that I am connected to Kanders through their professional associations,” he told artnet News.

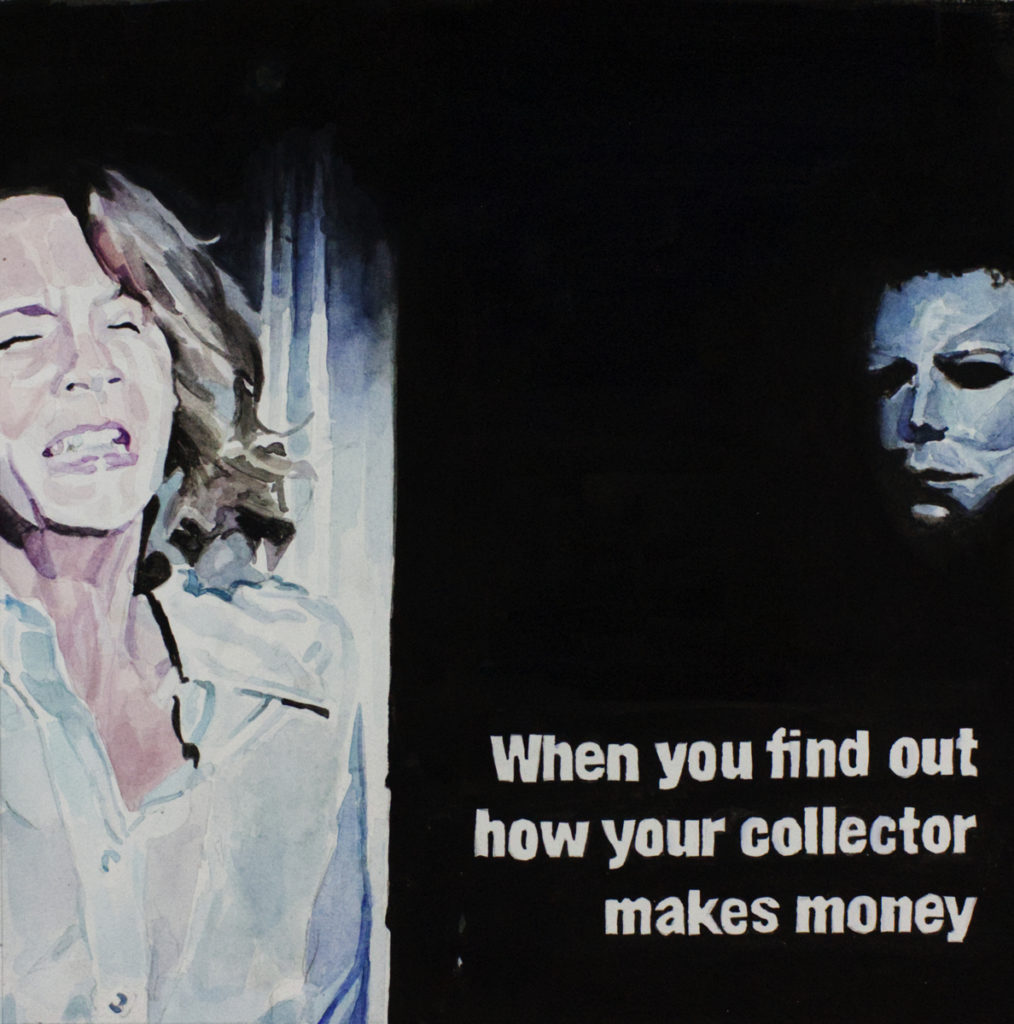

Another large drawing, about the now well-publicized dealings of the Sackler family, is laid out like a family tree, complete with monetary accounts of their institutional gifts to the Whitney, the Met, the Victoria & Albert Museum, Tate, the Dia Art Foundation, and many other arts entities. Powhida includes the monetary amounts each museum received, along with their current status in accepting or rejecting further association. (All have now distanced themselves with the exception of Dia, which still has not commented on the multimillion-dollar Sackler Wing endowment it received in 2016.)

Artist Nan Goldin makes a cameo appearance too, representing her role as part of the protest group PAIN. She stands as a symbol for successful critique leading to actual change, Powhida said. “Nan’s work is an example of how this can work.”

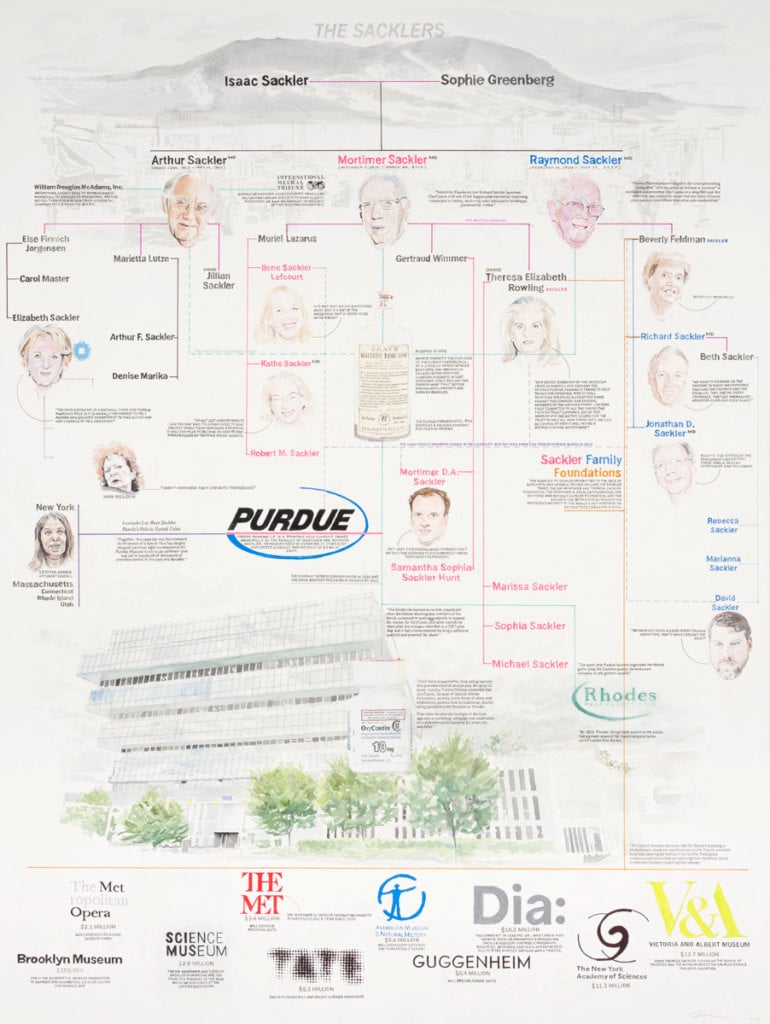

Another drawing focuses on a place: Hudson Yards, the hulking “city within a city” that, after years of construction, seemed to bloom overnight at the terminus of the 7 train in New York this year. Hudson Yards has been in the news lately too, on account of the much-scrutinized role of mega-developer Stephen Ross in fundraising for Donald Trump.

This work features an image of the complex of buildings on the Hudson Yards site. All of the governmental proceeds, building permits, investors, tenants, and other logistical minutiae related to the site are meticulously laid out. It’s a startling amount of information to take in—though, as Powhida points out, this is actually just a part of the complexity of what the final luxury complex will represent, since it is still expanding. “This is only phase one of the project!”

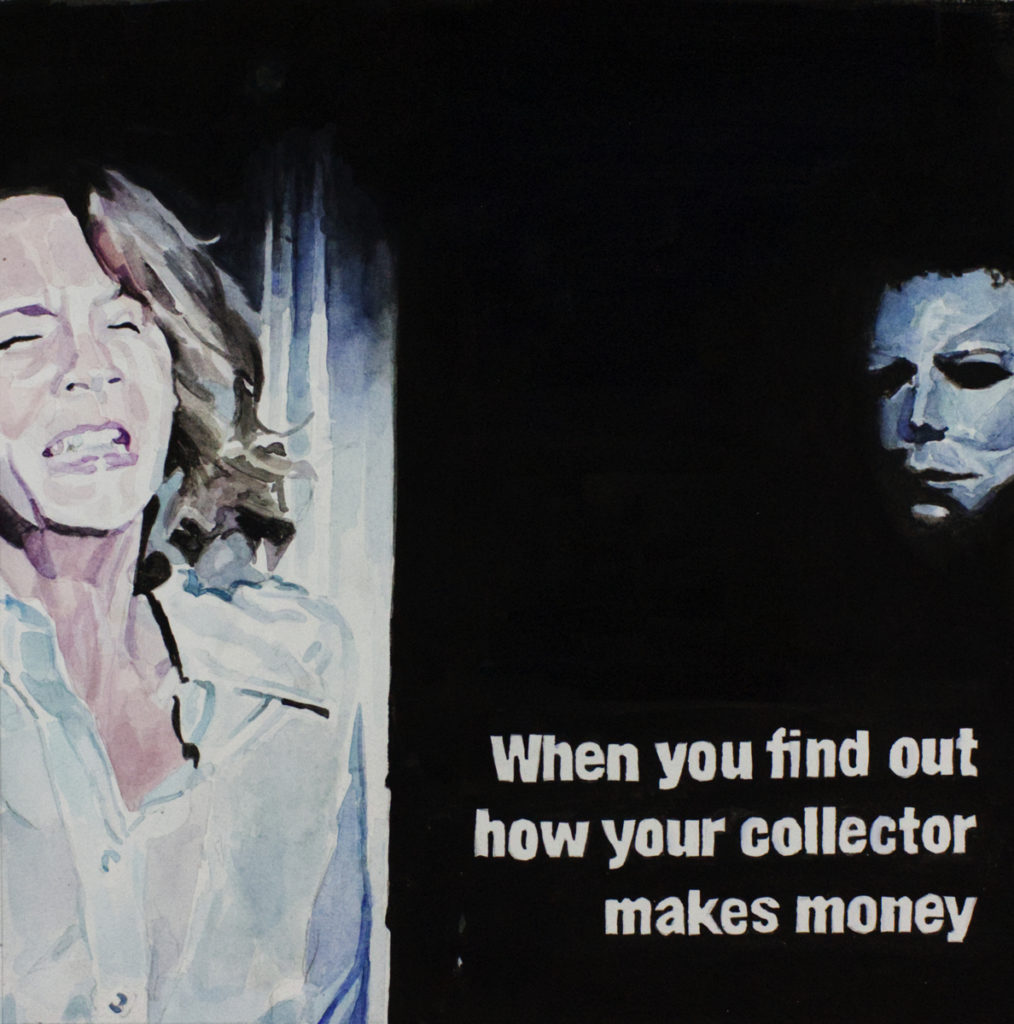

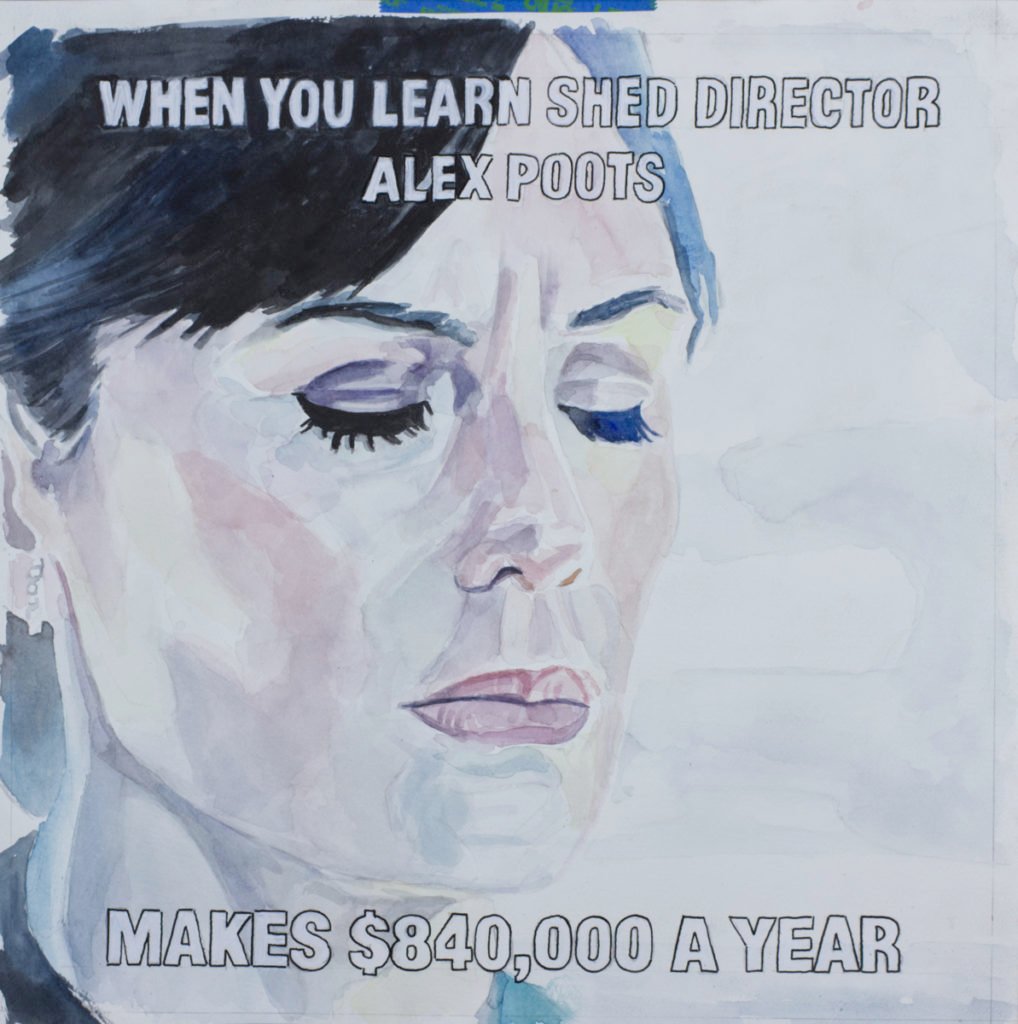

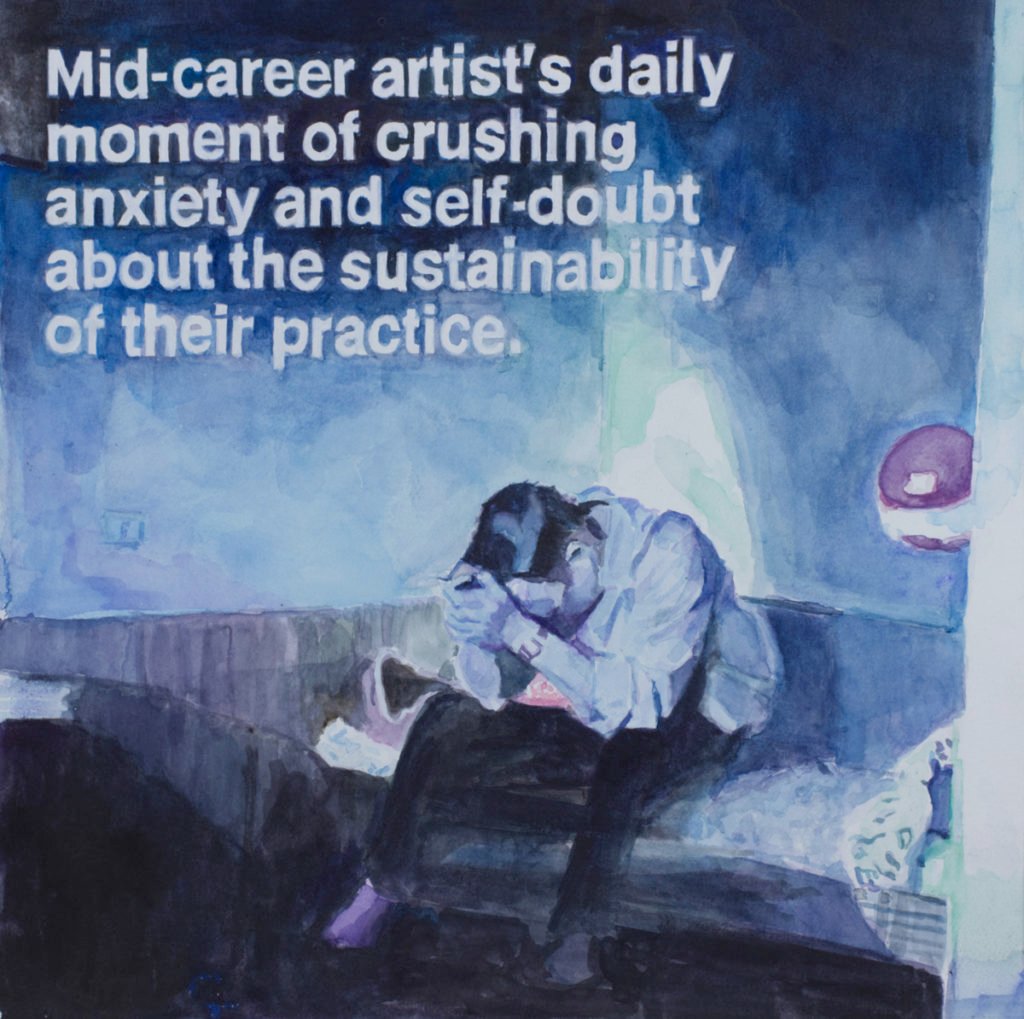

Adding some levity to the data-heavy works on display are small watercolor paintings in the style of memes, overlaying movie stills from horror films (Don’t Look Now) and premium cable drama series (Billions) with block text that captures the angst of being an artist in 2019. One pictures Jamie Lee Curtis’s character from Halloween squeezing her eyes shut as she hides behind a door, her face twisted in a grimace as the masked murderer Michael Meyers lurks in the black background. The overlaid text reads: “When You Find Out How Your Collector Makes Money.”

William Powhida, The Sacklers (Family Tree) (2019). Courtesy of the artist and Postmasters Gallery.

The idea—rendering a quick-fire internet joke as a carefully rendered drawing—adds a dose of the artist’s self-deprecating irony.

This brand of sly but serious satire is nothing new for Powhida, who in 2009 indicted the museum world with a detailed, caricature-filled work called How the New Museum Committed Suicide with Banality, which called out the New York-based museum—founded on the idealist, populist ethos of the late Marcia Tucker—for turning over the space to mega-collector Dakis Joannou (his favorite artist is Jeff Koons) to organize a show.

And, yes, he knows he’s a privileged white guy. He told artnet News that he has taken some inspiration from Xaviera Simmons’s piece in the Art Newspaper, “Whiteness must undo itself to make way for the truly radical turn in contemporary culture,” which, with Simmons’s permission, he quotes in the material for this show. (Powhida had been set to speak at a workshop led by Simmons on the subject as part of the New Museum’s IdeasCity Bronx, before Simmons cancelled it in solidarity with Bronx art groups that pulled out of the festival after protests from community members.)

In some small way, Powhida sees his maps of family wealth and institutional power as part of the conversation Simmons was trying to have. White supremacy, he says, is more than neo-Nazis in Charlottesville; it’s a deeply ingrained “system of privilege and accumulated advantages that can land a twenty-something on the board of Dia.”

See more images from the show, below. “Complicities” is on view at Postmasters Gallery through October 12.

![William Powhida, The Sacklers (Family Tree) (2019) [detail]. Photo: Caroline Goldstein, courtesy of Postmasters Gallery.](https://news.artnet.com/app/news-upload/2019/09/Image-from-iOS-6-1024x768.jpg)

William Powhida, The Sacklers (Family Tree) (2019) [detail]. Photo: Caroline Goldstein, courtesy of Postmasters Gallery.

![William Powhida, The Sacklers (Family Tree) (2019) [detail]. Photo: Caroline Goldstein, courtesy of Postmasters Gallery.](https://news.artnet.com/app/news-upload/2019/09/Image-from-iOS-5-768x1024.jpg)

William Powhida, The Sacklers (Family Tree) (2019) [detail]. Photo: Caroline Goldstein, courtesy of Postmasters Gallery.

William Powhida, Hudson Yards Phase I (2019). Courtesy of the artist and Postmasters Gallery.

William Powhida, Alex Poots< (Billions) (2019). Courtesy of the artist and Postmasters Gallery.

William Powhida, Textron (Indirect Investments) (2019). Courtesy of the artist and Postmasters Gallery.

Installation view, “William Powhida: Complicities.” Courtesy of Postmasters Gallery.

William Powhida, Crushing Anxiety (Chernobyl) (2019). Courtesy of the artist and Postmasters.