Art & Exhibitions

Run to See Agnes Martin at the Guggenheim, Then Stay a While

Martin's paintings quietly inhabit their own special niche of art history.

Martin's paintings quietly inhabit their own special niche of art history.

Ben Davis

About midway through the chronological sweep of the Guggenheim’s serene Agnes Martin show, there’s a moment of unexpected funk, a cluster of odd, uncharacteristic works from the late ’50s and early ’60s, a moment of transition for her. One, titled Burning Tree, resembles the business end of a hat rack, a crown, or a claw. It brims with quirky personality.

Agnes Martin, Burning Tree (1961). Photo Ben Davis.

If such a work particularly sticks out, it’s because Martin had a habit of willfully purging from the record any works that she didn’t think captured her final vision of what her work was supposed to be. And so Burning Tree throws into relief how an artist whose most famous work might seem, at first glance, almost voided of subjectivity in fact represents the most forceful possible subjectivity.

The Guggenheim’s show, which is co-curated by Tracey Bashkoff and Tiffany Bell, and previously appeared in London and Los Angeles, features over 100 works in all. Its opening section shows Martin sorting through abstract painting, moving from diaphanous, biomorphic shapes to floating configurations of eccentric geometry.

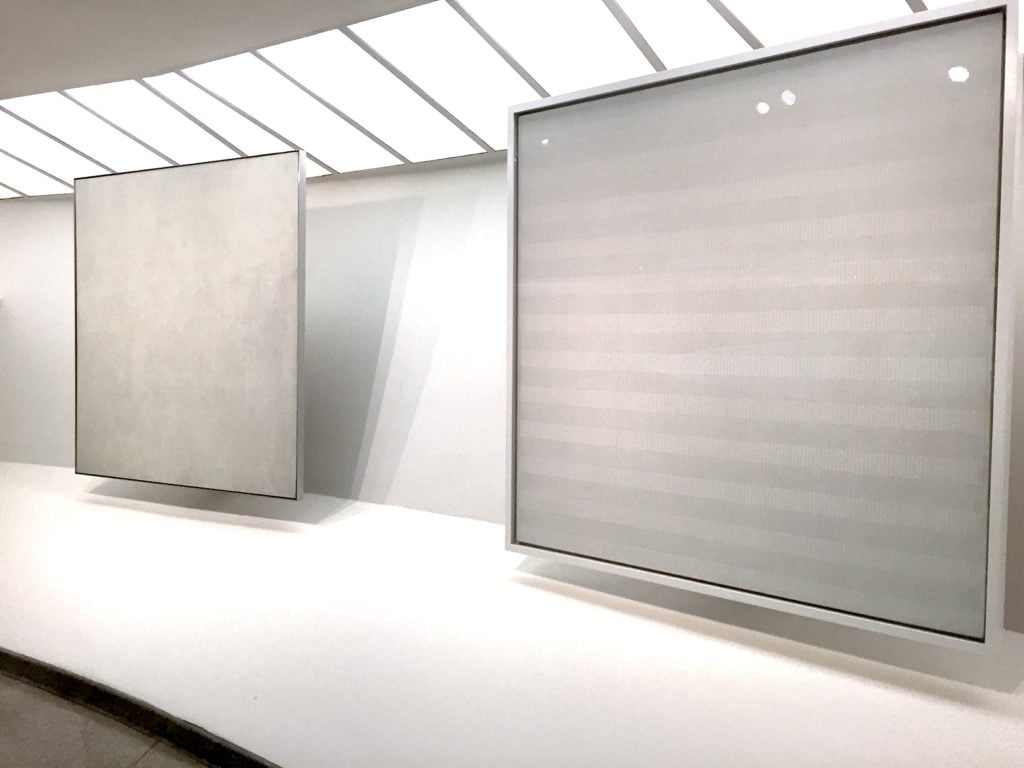

Agnes Martin, White Stone and The Tree (both 1964) at the Guggenheim. Photo Ben Davis.

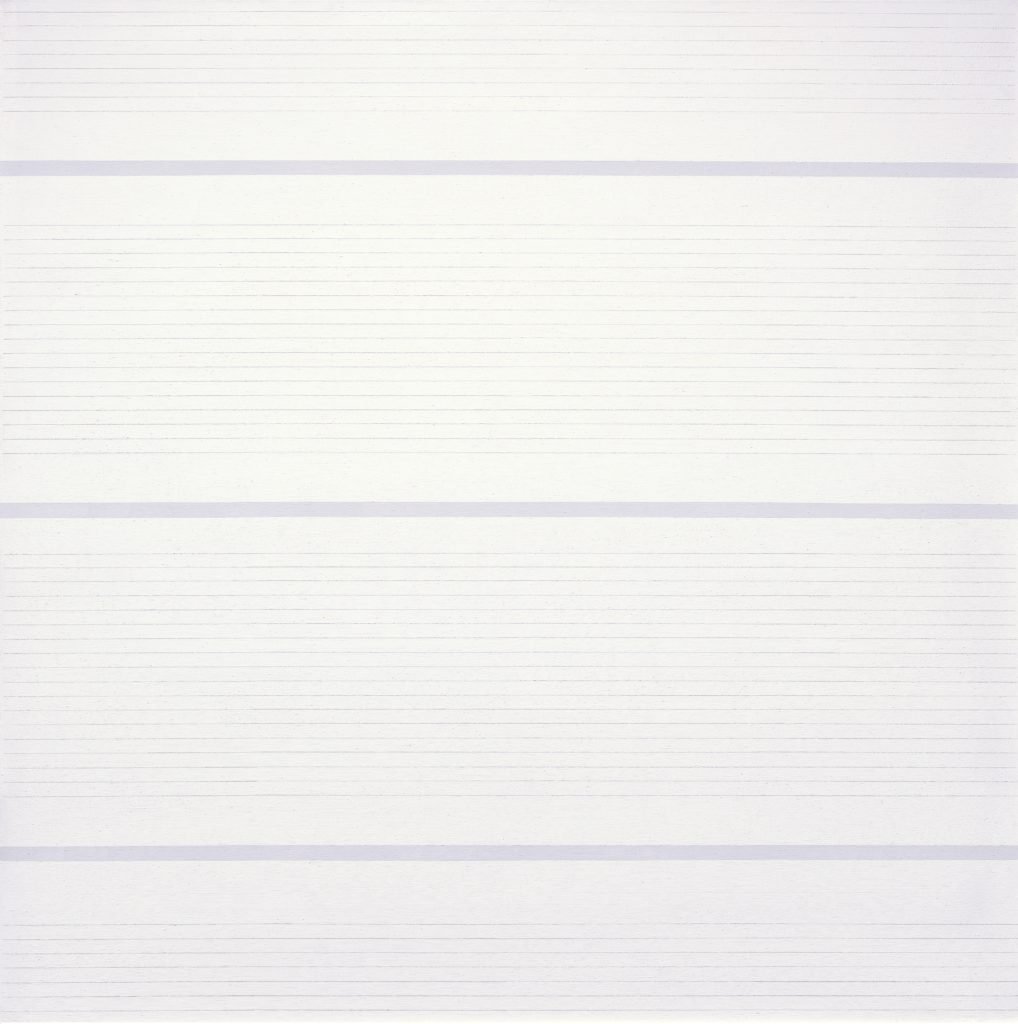

Then, she discovers the grid, the motif she became known for—close-knit, austere grids of lines, so fine that they barely register in photographs, set off against the background of evenly painted canvas. Martin spent much of her mature career working in exactly the same format, over and over, finding new ways to divide up the space into these rhythmic fields.

A 1963 work, Friendship, rehearses the grid motif in gold leaf. Martin manages to make even gold look mellow and un-ostentatious.

Agnes Martin, Friendship (1963). Photo Ben Davis.

You don’t need to know Martin’s biography to like this work; you just need the time and patience to appreciate her refined sensibility. Nevertheless, here is some biography: She was born in Saskatchewan, Canada, in 1912, and discovered by legendary art dealer Betty Parsons in the late ‘50s.

She had, therefore, been painting for many, many long years before she showed. In the meantime she had lived all over the country, attending school in Bellingham, Washington, and New York, at Columbia University’s Teacher’s College, ending up in the artist community of Taos, New Mexico. She worked as a teacher, waitress, and many other odd jobs, including as a liaison for a lumber company.

Agnes Martin, Untitled #2 (1992). © 2015 Agnes Martin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

In the ‘60s, after meeting Parsons in Taos, she moved to New York, where she found enviable success—only to drop out abruptly in 1967, for mysterious reasons. She would spend years more wandering, finally settling in rural New Mexico, where she lived in self-imposed solitude.

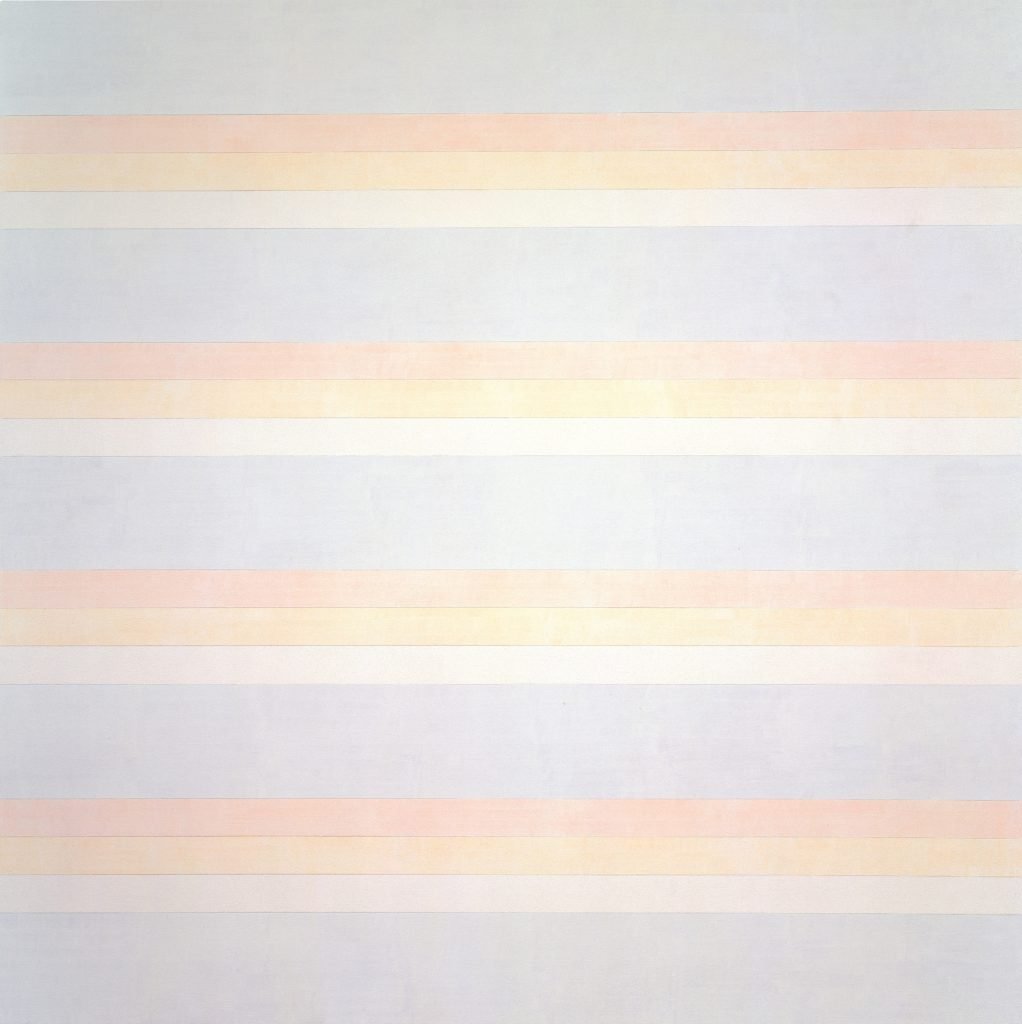

Martin returned to art in the ‘70s with new paintings characterized by subtle, atmospheric bands of hazy colors, glimpsed in the final stretch of the Guggenheim show.

One detail of her biography that has received increasing attention is her battle with mental illness: Martin was diagnosed with schizophrenia as a young woman, and experienced auditory hallucinations. Her obsessive grids do have the feeling of a salving ritual, holding together the world through creating a kind of ideal order.

“It was urgent to her to establish, one after another, these experiences of transcendent calm,” art historian and critic Nancy Princenthal, author of an award-winning biography of Martin, hypothesized recently in an interview.

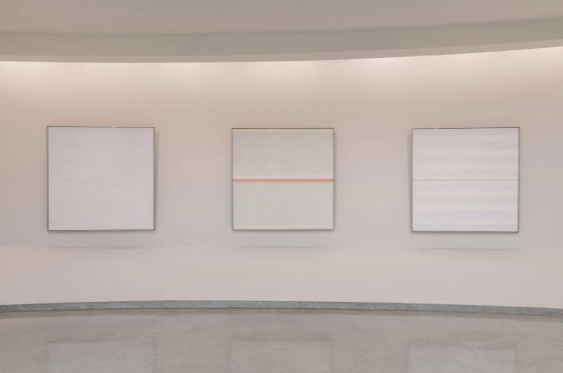

Agnes Martin, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, October 7, 2016–January 11, 2017. Photo David Heald.

Yet Princenthal also thinks that Martin’s reputation as a “seer of the desert” is overdone, and distracts from how canny she was as a painter. “It was part of her, but it didn’t define her,” she says of Martin’s mental illness. Just so. Encoded in Martin’s works, one finds a very deliberate conversation with her artistic peers about what painting could and should be.

When Martin came to New York, Abstract Expressionism was at the peak of its prestige, and Minimalism was beginning its incursion. Her grid paintings are often thought of as a kind of joint between these two movements. This is understandable, but a bit pat.

“I was sort of driven away by the lust of the young painters wanting to be so successful,” Martin would say later of her departure from New York in 1967. She could easily have been speaking of Frank Stella, a brash tyro who broke on the scene at the same historical moment Martin was finding her signature in her mid-40s. Stella often gets described with the exact same formula, as mediator between Ab-Ex and Minimalism.

Agnes Martin, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, October 7, 2016–January 11, 2017. Photo David Heald.

The Abstract Expressionists were all about developing characteristic tics in paint: Jackson Pollock = drips; Robert Motherwell = blots; Barnett Newman = zips. Martin, for her part, spoke frequently about the importance of renouncing “pride” and ego in her art, and one gets the sense that the grid attracted her because it was ego-less, eliminating overheated, subjective effects.

The machined perfection of the Minimalists, on the other hand, was “non-subjective” in a negative way, in Martin’s assessment: “They want to minimalize themselves in favor of the ideal.” This was not her jam. “The object of painting,” she would say, “is to represent concretely our most subtle emotions.”

Both Martin’s gridded compositions and Frank Stella’s abstract stripes convey a sense of “deductive structure,” art historian Michael Fried’s term for how Stella’s visual content was derived from the shape of the canvas itself. Neither artist overspills the canvas or suggests visual expanses beyond their edges. They are self-contained. “What you see is what you see,” as Stella put it.

Agnes Martin, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, October 7, 2016–January 11, 2017. Photo David Heald.

But in Stella’s case, the repressed ego of Abstract Expressionism returns at a higher level—the freedom he represses in the image returns big time in the freedom he gives himself to treat the canvas itself as a sculpture. And so, as the recent Stella retrospective of his work at the Whitney showed, his works quickly get more and more baroque and bombastic; by 1967 he was well into his “shaped canvas” phase. Martin, meanwhile, pretty much kept her canvases the same size once she hit on what felt right: six by six feet, the scale of the human body, the better to be grounded in human experience.

You could say that Frank Stella took the thesis of Abstract Expressionist ego and the antithesis of Minimalist cool and created some wild new synthesis of the two. Martin, on the other hand, hovers serenely in the magnetic field between the two poles, in the meditative place where the personal and impersonal overlap.

Agnes Martin, Untitled 15 (1988). Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Her lines are rendered in graphite, and that’s important. Graphite is a precise medium, but one that registers the effort it takes to achieve that precision. Martin’s patterns are always rigorous. As you sit and look into them, though—which is what you should do—you slowly see in her marks the effort that it took to achieve this level of renunciatory rigor.

The result is that each canvas unfolds as a story, the drama of the human mind straining towards a state of clarity. And the movement between each canvas testifies to how such clarity is a process perpetually pursued, not a state finally achieved. They are solitary paintings, maybe, but they communicate beautifully.

“Agnes Martin” is on view at the Guggenheim Museum, though January 11, 2017.