Art & Exhibitions

A New Exhibition of Harper’s Bazaar’s Glory Days Quietly Suggests That Fashion Magazines’ Best Moments Are in the Past

The show, at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, feels a bit like a wistful eulogy.

The show, at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, feels a bit like a wistful eulogy.

Noor Brara

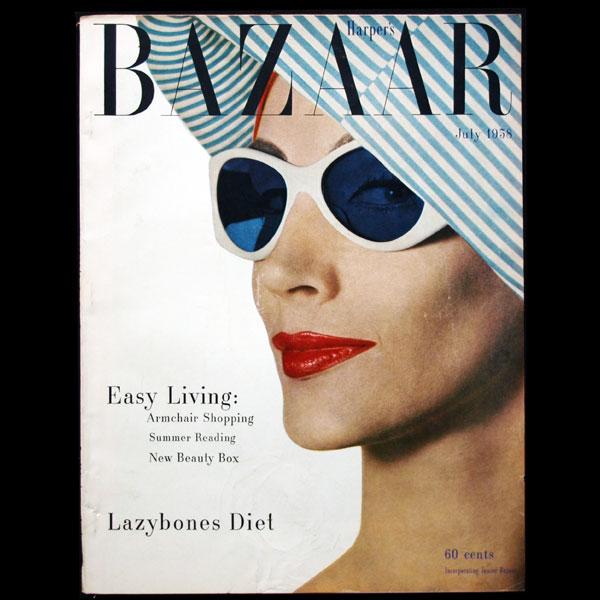

A July 1958 cover of Harper’s Bazaar features a coquettish, red-lipped model wearing white-rimmed sunglasses and a striped sun hat. She peers out at the viewer through a cool blue lens, the corners of her mouth pricking upward. “Easy Living,” the text beside her croons. “Armchair Shopping. Summer Reading. New Beauty Box.” Then, a little further down the page: “Lazybones Diet.”

The publication captures a moment in time—and, since then, things have changed considerably. Fronting a recent Bazaar issue, for example, is Gwyneth Paltrow posing in a futuristic Tom Ford breastplate, surrounded by articles promising to help readers recycle their wardrobes, wear suits, and “ignore” diet trends. Some would go so far as to say that, in recent years, women’s media has transformed into a different genre altogether, with many titles cutting down their pages-long fashion spreads to make room for features on the upcoming presidential election, women’s rights, gun violence, and climate change. Celebrity features like Paltrow’s, meanwhile, are now all about getting raw, real, and, on occasion, downright weird: in her Bazaar cover story, the wellness-company founder talks about Goop enterprise’s experiments with new age-y fads like MDMA therapy and “snowga,” a form of yoga that begins with bathing in ice water for extended periods of time.

Yet despite these publications’ best efforts to keep up with their readers’ varied interests and rapidly waning attention spans, the future of print media hangs perpetually in the balance, with things looking especially grim for the glossies. Simply put: it is no longer enough to just make magazines. And it may prove not to be enough even with the bells and whistles of their accompanying digital “extras.”

The question then becomes: when is time to start preserving and exhibiting fashion magazines as historical relics?

A scene from Harper’s Bazaar’s August 2009 issue, shot by Peter Lindbergh. Image courtesy the Musée des Arts Décoratifs.

As if in response to the shifting sands, the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris has decided to celebrate the reopening of its fashion galleries with an exhibition dedicated entirely to Harper’s Bazaar, opening on February 28th. Titled “Harper’s Bazaar: First in Fashion”—a nod to the magazine’s place as the first publication formed to cover the style world—the show chronicles the major contributions of Bazaar to fashion over the course of its 152-year history.

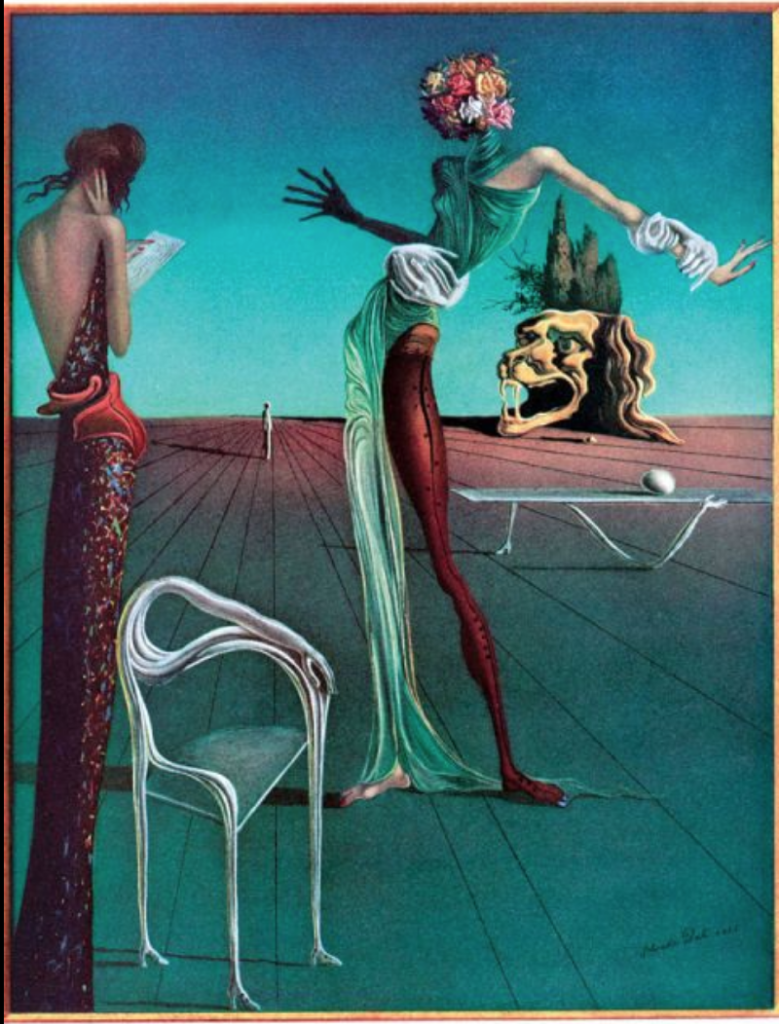

Sixty couture and ready-to-wear looks from the museum’s collection will be displayed alongside images of how they appeared in print, photographed and illustrated by frequent Bazaar contributors including Andy Warhol, Man Ray, Richard Avedon, Hiro, and Peter Lindbergh. There will additionally be special tributes to three of the magazine’s most powerful editors: Carmel Snow, the editor-in-chief who famously dubbed Christian Dior’s revolutionary first couture collection the “New Look”; art director Alexey Brodovitch, who commissioned artists like Salvador Dalí, Jean Cocteau, Marc Chagall, Leonor Fini, and famed French poster artist A.M. Cassandre to create original work for the magazine; and editrix Diana Vreeland, whose unprecedented tongue-in-cheek editorial sensibility imbued the publication with more color and humor than ever before, and whose work for the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute long preceded Anna Wintour’s Met Ball.

Salvador Dalí’s 1935 illustration for Harper’s Bazaar. Image courtesy Getty Images.

Still, the exhibition—curated chronically across two floors—does little to frame Bazaar as a thriving present-day cultural barometer, instead reflecting its curators’ admission that the future of magazines is uncertain and that the time to begin archiving them is, well, now. “The context of the media and magazines is slowly changing with the arrival of the internet,” say Eric Pujalet-Plaa and Marianne Le Gaillard, who co-organized the exhibit. “We do not know what will come in 10 or 15 years. I think it’s important to show now, at this moment of upheaval, that Harper’s Bazaar participated deeply in the visual history of the 20th century, and that its innovations were—and still are—highly related to human synergy.”

In many respects, that’s true. Bazaar was founded in 1867 by Harpers & Brothers (the same publishing house behind Harper’s Magazine and the flagship imprint of HarperCollins books) to focus not only on fashion but on society, the arts, and literature as well. Its first editor was, interestingly, a suffragist and abolitionist named Mary Louise Booth, who was a fierce advocate for the Union cause during the American Civil War. At the time, in addition to teaching the world about style, Bazaar published stories on such leading American artists as Frank Stella and Jackson Pollock, running them alongside literary contributions from writers such as Colette, Simone de Beauvoir, Charles Dickens, Virginia Woolf, Patricia Highsmith, and Truman Capote.

Despite all this, Bazaar’s imagery is what really set the magazine apart, providing a visual launching pad for designers like the great Charles-Frederick Worth, widely considered to be the father of couture; Paul Poiret; Jeanne Lanvin; Madeleine Vionnet; Elsa Schiaparelli; Dior; and Cristóbal Balenciaga, whose work, as seen in Bazaar, garnered major attention and support from the well-heeled doyennes of American high society.

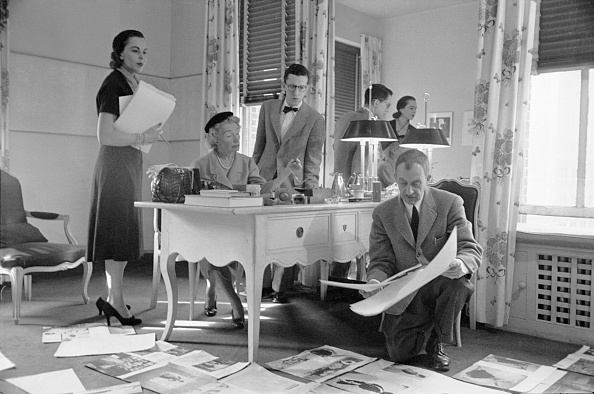

By the 1950s—during the collective reign of Snow, Vreeland, and Brodovitch, who were known together as the “Holy Trinity”—Harper’s Bazaar had become such a force in fashion that it featured prominently in Audrey Hepburn’s Funny Face, with the film spoofing its particular workplace culture (and its editors’ mercurial temperaments) à la The Devil Wears Prada.

Editor-in-chief Carmel Snow and art director Alexey Brodovitch at the Bazaar offices in New York, December 1952. Photo by Walter Sanders/The LIFE Picture Collection via Getty Images.

But transforming all this rich history for a standalone exhibition has, understandably, proved difficult in more ways than one, not least because there’s simply too much available material. “To exhibit a magazine is particularly challenging,” Pujalet-Plaa and Le Gaillard told Artnet News in an email. “Nonetheless, it was very exciting to observe how the graphic compositions and the editorial content of Harper’s Bazaar creates spectacular stagings for clothes, all different and changing over time. It also helped us understand how the museum’s fashion collection, often shaped by private collectors’ choices, is highly dependent on Bazaar. We hope the public will be as fascinated as we are by its rich and innovative content, made for, in Snow’s words, well-dressed women with well-dressed minds.”

Per Pujalet-Plaa and Le Gaillard, each vitrine in the show has been modeled as a time capsule, linking the clothes to their reproductions on the page. The pacing will move chronologically, centered on the clothes—which means that the rollicking stories of Bazaar’s editors, models, and contributors and the behind-the-scenes, human history of the magazine’s exploits (sadly) won’t be a central focus of the show.

“The history of Bazaar is of course full of charismatic personalities, but we were afraid it would confuse the viewers,” Le Gaillard said. “So we favored a chronological approach from 1867 to present. Harper’s Bazaar has always been praised for its unity between fashion and the arts, so we wanted to pay homage to that in the exhibition. We could have gone for a more interdisciplinary display, with, for example, specific vitrines devoted to particular relationships, but considering the complexity of the subjects and the involvement of so many directors and contributors, we felt this was the best way.”

Diana Vreeland at home in her “garden in hell” living room. Photo by Horst P. Horst/Conde Nast via Getty Images.

A few weeks ago, it was announced that Bazaar’s longtime editor-in-chief, Glenda Bailey, would be stepping down at the end of February. For her final act as editor, she’ll inaugurate the opening of “First in Fashion,” signaling the end of her 19-year reign, the results of which will feature behind glass vitrines as part of the magazine’s catalogued history. Fashion critic Vanessa Friedman at the New York Times recently wrote about the bittersweet nature of Bailey’s swan song’s coinciding with the exhibition:

“In the contrast between what will be on the wall and what is often on the page, it will underscore just how much Bazaar changed during Ms. Bailey’s tenure as she shepherded the magazine into the era of Instagram and reflected its ethos. Which is to say, the era of eroding authority of glossies, the rise of the armchair influencer, and the commodification of creativity.”

Perhaps even more poignant is the fact that Bailey’s replacement has not yet been named, and still may not be by the time of the exhibition’s opening. (According to the ever-reliable New York Post, Hearst is struggling to fill the position, having failed to tempt their top candidates—including In Style’s Laura Brown, WSJ Magazine‘s Kristina O’Neil, and The Cut’s Stella Bugbee—away from their current posts.) On February 29th, the second day of the museum show, it’s entirely possible that Bazaar will be without an editor, its face—literally, figuratively—and future unclear.

But one thing seems certain: magazines will likely never again see an editorial regime with the same resources to spend on an opulent creative vision as existed under Bailey and her predecessors. With the departure of every major editor-in-chief, traditional publishers are slashing salaries and cutting costs more and more ruthlessly, bringing to a close the era of fantastical images and boundary-pushing photography that only massive photo budgets could allow. In all likelihood, Bailey—who famously shot Rihanna swimming with very real sharks in one issue, and placed Demi Moore atop a tall stair to feed a giraffe in another—will be replaced by someone younger, more affordable, with far less creative leeway.

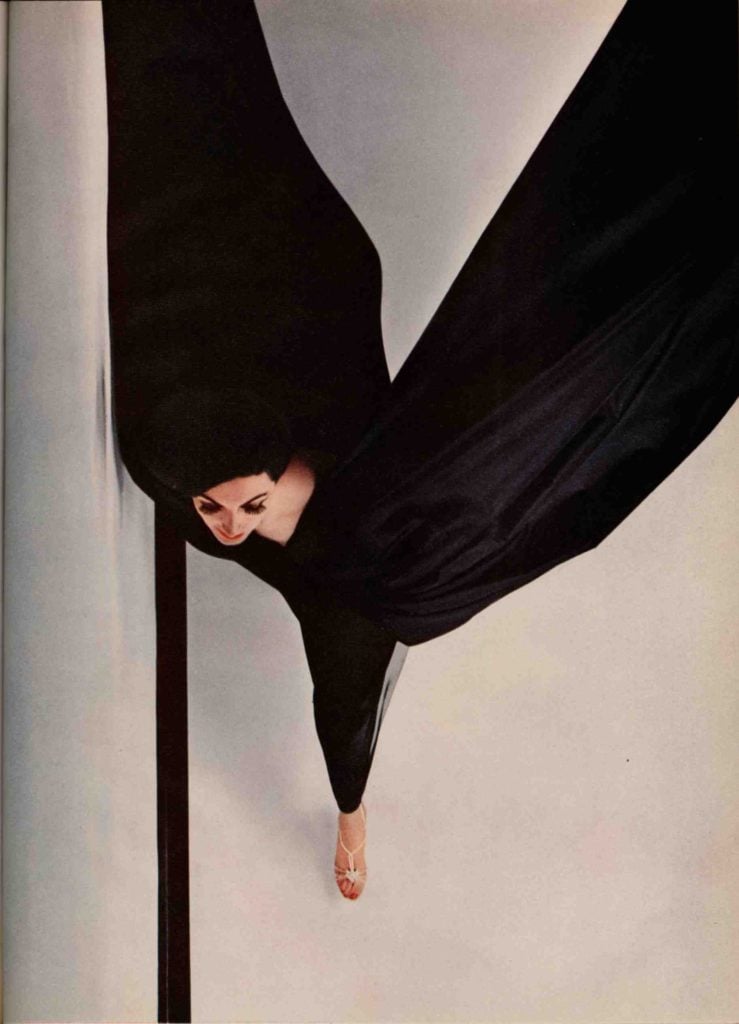

A shot from Harper’s Bazaar’s October 1963 issue, shot by Hiro. Image courtesy the Musée des Arts Décoratifs.

It’s perhaps all the more reason to visit “First in Fashion,” if only to walk down Bazaar’s star-studded memory lane, when the cash was flowing and editors were encouraged to do things like fly to the snow-covered mountains of Japan in December to photograph 26 pages’ worth of of luxurious winter furs; to capture the languid bodies of suntanned models melting into poolside recliners in order to perfectly illustrate whatever the “Lazybones Diet” was; to run a column entirely comprised of ridiculous questions that celebrate frivolity and excess and silliness, asking, “Why don’t you rinse your blond child’s hair in dead champagne to keep it gold, as they do in France?” or “Why don’t you have the most beautiful necklaces in the world made of huge pink spiky-coral with big Siberian emeralds?”

These are Bazaar’s most delicious moments, and all signs point to the notion that they will remain that way.

“’Harper’s Bazaar: First in Fashion’ is the first exhibition dedicated to a fashion magazine that looks beyond the photographs to the impact of its editorial and artistic direction, the design and the men and women behind it all, as it explores how magazines have helped define what fashion is and what we consider fashion,” the curators note. “It became obvious that it was time to celebrate Bazaar. And as Carmel Snow would say, ‘It is essential to have a finger on the pulse of the times.’’