For Edward Hopper, a rugged coastline or rural highway could be as psychologically charged as a café at night or a deserted city street. But the American artist’s landscapes tend to get overshadowed by his more famous paintings evoking urban isolation.

That is set to change with an exhibition opening this week at the Fondation Beyeler in Switzerland that focuses on the American artist’s paintings of rural scenes. Hopper, who grew up in upstate New York and spent nearly every summer from the 1930s to the ’50s on Cape Cod, was “always playing with the expectation of the viewer and triggering something unconscious,” Ulf Küster, a curator at the Fondation Beyeler, told Artnet News.

The show explores how Hopper used the same canny techniques to evoke a sense of uncertainty and heavy pathos in his landscapes and city scenes alike. “He is deliberately not doing traditional landscape,” Küster says.

Edward Hopper, Bridle Path (1939). Private Collection.

Among the loans from private collections is Hopper’s 1939 painting Bridle Path, which epitomizes the artist’s ability to inject an unsettling note of drama into his compositions. It shows three riders galloping towards a tunnel in New York’s Central Park with the famous Dakota building in the background. The white horse with a male rider appears spooked, while the horses of his female companions charge ahead. The date of the painting—1939—perhaps offers an explanation for its ominous atmosphere. Hopper, who had spent time in Paris as a young artist, may have been thinking about the increasing threat of war in Europe.

How did Hopper manage to evoke this sense of foreboding and mystery in his work, regardless of the subject? Often, Küster explains, by creating a tightly cropped composition that suggests more action is taking place outside the picture plane, as in Bridle Path, or by including people who are looking at something that is invisible to the viewer.

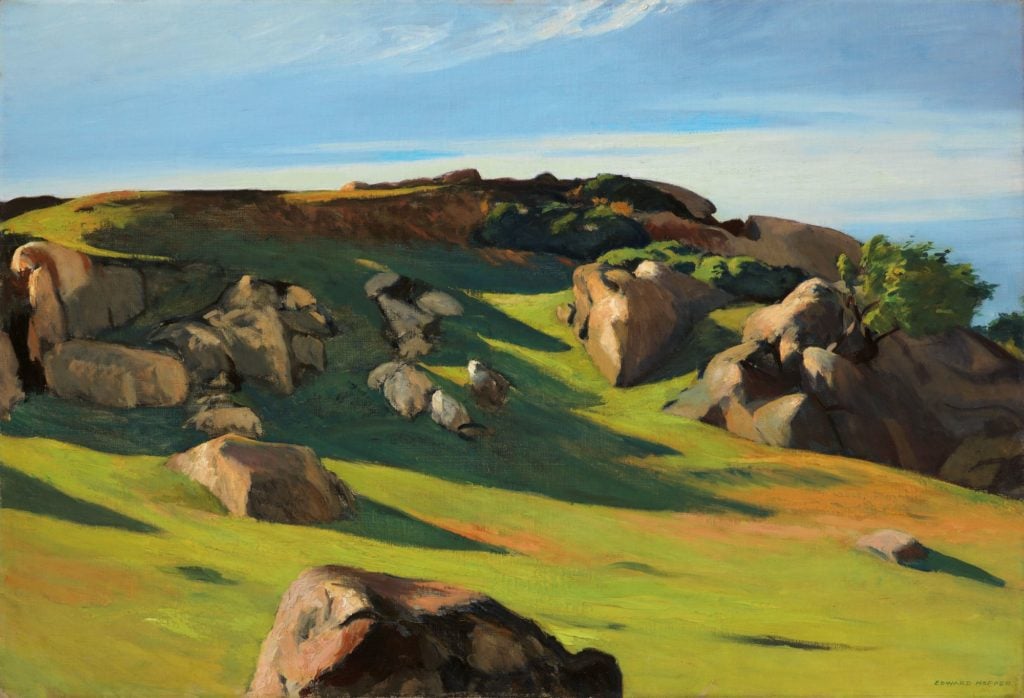

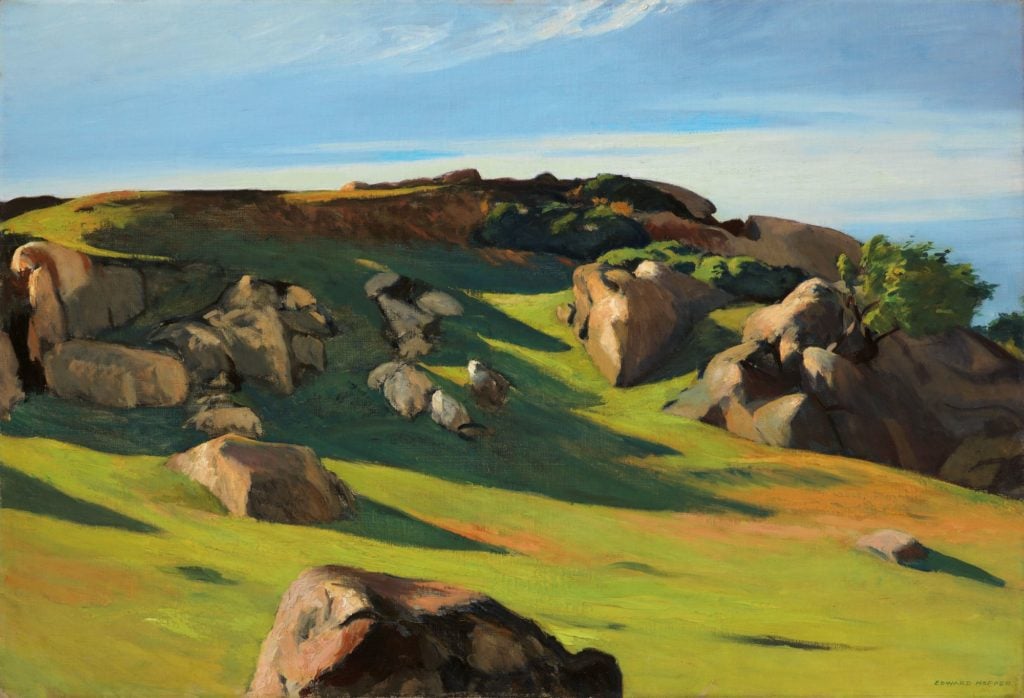

Consider another key and rarely seen painting in the show: Hopper’s Cape Ann Granite (1928). A long way from a conventional seascape, it pictures rocky outcrops that cast ominous shadows across the painting; the sea can only be glimpsed in the corner of the canvas, giving the viewer a sense of uncertainty about what lies beyond.

Edward Hopper, Cape Ann Granite (1928). Private Collection © Heirs of Josephine Hopper / 2019, ProLitteris, Zurich.

That picture was once owned by David Rockefeller and was, in fact, the catalyst for the entire exhibition. Its anonymous new owner bought it in the headline-grabbing auction of David and Peggy Rockefeller’s collection in 2018 and has since placed it on long-term loan to the Swiss private museum, inspiring curators to look further at Hopper’s work.

An exhibition of the American Modernist in Europe is an undeniably rare event. Most of Hopper’s paintings are held in North America; only five of his oil paintings are in European collections. The Beyeler worked closely with the Whitney Museum of American Art, which has an unrivaled Hopper collection, to pull off the show. “They are national treasure in the US,” the curator says.

See below for highlights of the Beyeler’s exhibition.

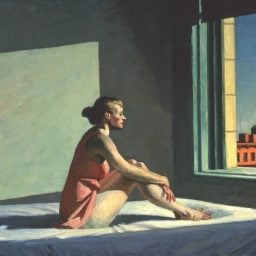

Edward Hopper, Cape Cod Morning (1950). Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of the Sara Roby Foundation © Heirs of Josephine Hopper / 2019, ProLitteris, Zurich. Photo: Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gene Young

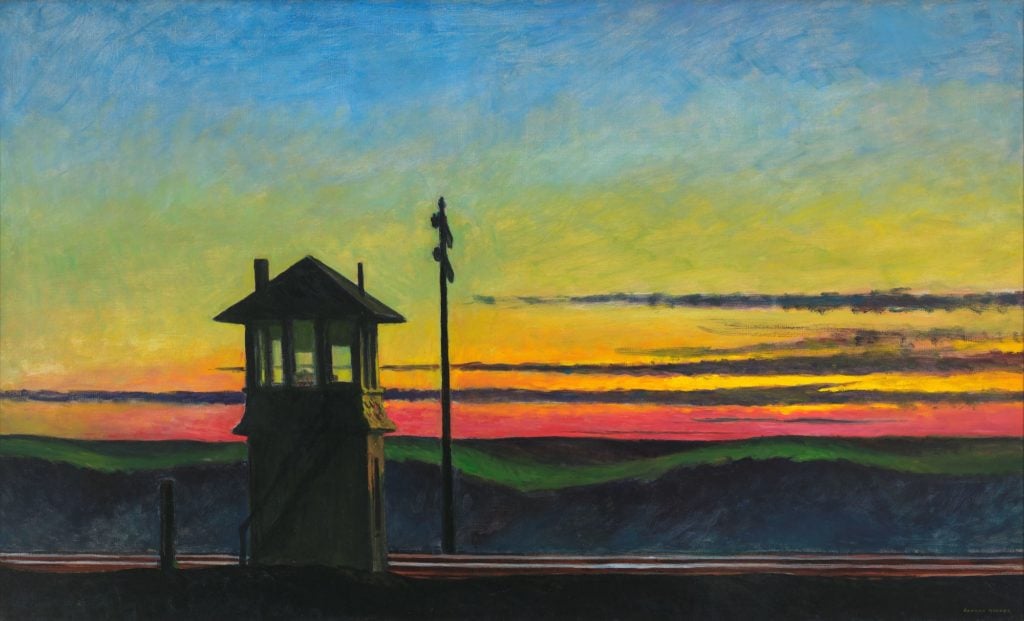

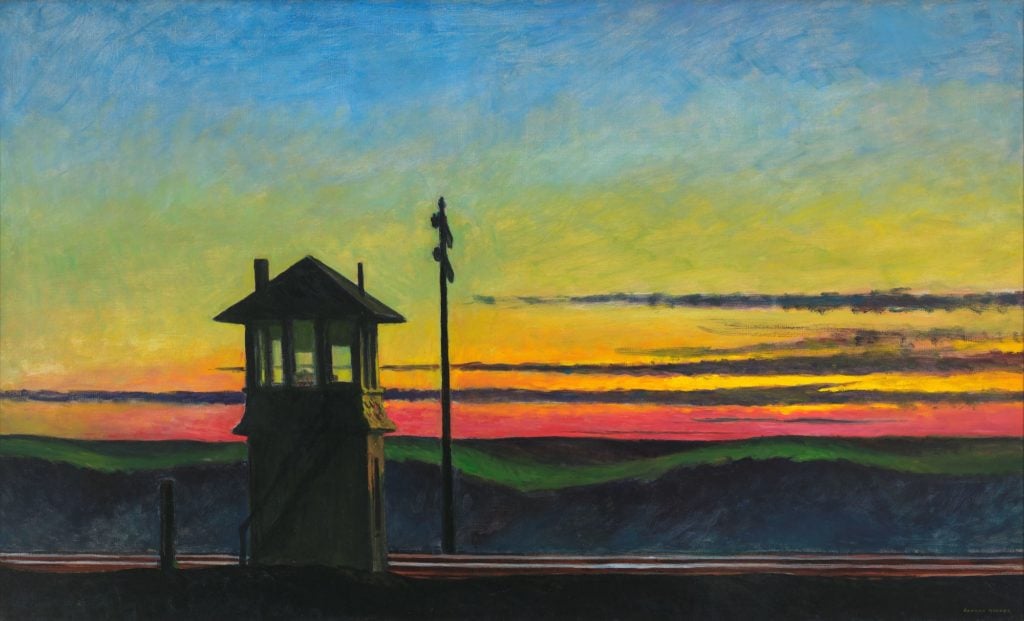

Edward Hopper, Railroad Sunset (1929). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Josephine N. Hopper Bequest, Inv. N.: 70.1170. © Heirs of Josephine Hopper / 2019, ProLitteris, Zurich Photo: © 2019. Digital image Whitney Museum of American Art / Licensed by Scala

Edward Hopper, Second Story Sunlight (1960). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Purchase, with funds from the Friends of the Whitney Museum of American Art., Inv. N.: 60.54. © Heirs of Josephine Hopper / 2019, ProLitteris, Zurich Photo: © 2019. Digital image Whitney Museum of American Art / Licensed by Scala.

“Edward Hopper” is on view from January 26 through May 17 at the Fondation Beyeler, near Basel, Switzerland.