When you walk into the first floor plaza Los Angeles’s Hammer Museum, don’t forget to look up. The Los Angeles-based artist Carolina Caycedo has hung sculptures made of fishing nets that hover overhead like ethereal, bubble-shaped mobiles.

The nets came to Caycedo as gifts from friends or from local markets along the rivers she visits in Mexico, Colombia, Guatemala, and other Latin American countries while researching and working to protect water rights. But you don’t need to know these sculptures emerge from her activism to appreciate their idiosyncratic generosity. Plastic bottles holding colored water dangle playfully from the nets, catching the sunlight, their cheapness contrasting with the Hammer’s smooth architecture and stylish patio furniture. Their critique of polish and excess is matter-of-fact—not subtle, but not didactic either.

Carolina Caycedo, To Drive Away Whiteness/Para alejar la blancura (2017). Courtesy of the artist and Commonwealth and Council, Los Angeles.

Caycedo’s work sets a fitting tone for the Hammer’s 2018 “Made in L.A.” biennial. Its politics are embedded in its material, and, like many works in the show, it conveys no sense of entitlement. This is the most profound and palpable effect of a show made up predominately of women, queer artists, and artists of color: a marked tone shift away from the kind of insider-baseball pretensions that can often characterize ambitious group exhibitions like this, toward a social awareness that’s more deeply felt.

That this edition of “Made in L.A.” also feels familial—many of the artists move through common networks—contributes to the overall sense of connectedness. Some of these artists have previously shown and worked together or alongside one another to attempt to negotiate realities beyond the art world’s limited reach, making this show feel simultaneously like a snapshot of a particular community and a part of something bigger.

Beyond the Usual Suspects

Relative to other shows of its kind, the Hammer’s biennial, which was founded in 2012, has consistently been diverse. Twelve, or less than half, of the 25 artists in the 2016 “Made in L.A.” were male and many of them identified as neither straight nor white. This year, 23 out of 33 artists are female or gender-non-conforming, and 19 are of color. These demographics are not the show’s defining feature, but taking difference as a given rather than an exception feels refreshing in a literal way, as if someone reset the status quo’s homepage.

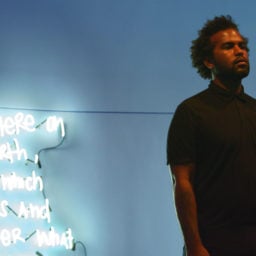

Daniel Joseph Martinez’s The Soviet memorial park in the district of Schönholz (2017). Courtesy the artist and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles.

The familial, overlapping networks are also quantifiable, to an extent: Nine artists, for example, have shown at Commonwealth & Council, a gallery that maintains the attitude of the artist-run space it once was, and 10 have shown at Human Resources, the communally-run alt space in Chinatown. As long as future iterations of the biennial steer away from this same extended group of artists, focusing on one particular slice of community makes sense. It pulls the show away from the sprawling, Whitney Biennial-inspired ambitions it’s had in the past and toward a more intimate regional portrait.

Curators Anne Ellegood and Erin Christovale intentionally chose to have no theme. But the show can clearly be read through the lens of community—how to preserve it, build it, how one’s body relates to the collective. In the year leading up to the exhibition, Ellegood and Christovale hosted a series of informal conversations between art workers—over lunch, at someone’s home—to talk about Los Angeles art now, an approach that, through its reliance on multiple networks and voices, reflects the show’s synergetic ethos.

The dependence on community also feels particularly timely given the current political situation and the increasingly precarious economics of Los Angeles, which have compelled many to create and rely on their own makeshift support systems.

Bringing LA Inside

Two artists raised in LA and included in the show, E.J. Hill and Lauren Halsey, negotiate their own relationships to specific corners of the city, emphasizing the kind of deep, ongoing engagement with neighborhoods that participation in a global art world can undermine. Hill’s installation documents private endurance performances he undertook this year: He ran circles around each school in Los Angeles he attended, from elementary to UCLA. The photographs of Hill’s engagement with his own local history (by Texas Isaiah) convey that mix of desperation and ecstasy that characterizes marathon runners.

Detail of Lauren Halsey’s Kingdom Splurge (2015). Installation view from “Everything, Everyday: Artists in Residence 2014–2015” Studio Museum in Harlem. Photo: Texas Isaiah. Courtesy the artist and Studio Museum in Harlem, New York.

While Hill’s work reads as an intimate exercise, Lauren Halsey’s project has ambitious, public aspirations. For The Crenshaw District Hieroglyph Project, Halsey installed an atrium of drywall and gypsum on the Hammer’s window-facing balcony. She gathered notations and images from family, friends, and other members of her South LA community and inscribed them into the gypsum, the same material used as mortar in Egyptian pyramids. Halsey intends to install a more developed version of the sculpture on Crenshaw Boulevard, inviting others to inscribe it themselves. In this case, the museum functions as testing ground for an in-progress idea that will live its fullest life in a much less pristine, more accessible environment.

While the 2014 “Made in LA,” meanwhile, actively incorporated artist-run ventures into the show (including Public Fiction and the Los Angeles Museum of Art), the work in this iteration occasionally integrates references to less formal kinds of artist support structures.

Carmen Argote’s installation, for example, includes a “drawing” made of coffee stains left behind by a sculpture Argote displayed at the collectively-run space PANEL LA last summer. To create the drawing, Argote built a kind of apparatus on the art space’s slanted back deck by laying paper on a platform and a coffee pot on either side. The coffee leaked and spread, drying in layers and mingling with the surrounding dirt and detritus.

Carmen Argote’s Platform with Mobile Unit (2017). Courtesy the artist and Panel LA.

As a leaflet accompanying the drawing at the Hammer explains, PANEL’s building abruptly sold in late 2017 to a developer who gave the collective a week to leave and threw out Argote’s sculpture before they could salvage it. The framed paper document, all that remains of that project, is much cleaner than the oozing, staining apparatus that created it, and its institutionally-appropriate sanitization serves as the by-product of a brutally escalating cycle of displacement (something faced, much more precariously, by the city’s low-income residents).

Who Is Invited, and Who Is Left Out?

The curators have printed portions of the conversations they had with members of the LA art community in the show’s catalogue. At one point, they discuss exclusion—how every community is defined as much by who’s left out as who belongs, and how institutions and dominant art-historical narratives have long excluded certain kinds of artists.

Luchita Hurtado’s Untitled (1970). Photo: Cole Root. Courtesy the artist and Park View/Paul Soto, Los Angeles and Brussels.

One of those who has been left out is Luchita Hurtado, the 97-year-old artist who belonged to many communities, including a contingent of Surrealists and the women’s movement in Los Angeles, but never achieved institutional attention. A small subset of her work is prominently displayed at the Hammer in the form of 11 paintings made in the 1970s. In one series, the artist paints herself looking down at her foreshortened body, breasts and feet framing a large apple, the patterns on a woven rug, or a wide blue sky. Simple, precise and vulnerable, these paintings position the body as frame for environment.

Meanwhile, a suite of paintings by Linda Stark, based in Los Angeles since the 1980s, tells a different story about inclusion—and how outside forces often shape who gets invited in. Her virtuosic Fixed Wave (2011) features undulating thick, perfect, green horizontal lines that move from one edge of the canvas to the other, comprising the skin of a woman’s pelvic region. Pubic hair takes the form of five blue waves out of which rises a uterus flanked by ovaries that resemble sea creatures.

Linda Stark’s Self Portrait with Ray (2017). Courtesy of the artist.

The newly formed Artist Acquisition Fund, founded by five LA-based artists and curators, bought and gifted the painting to the Hammer this winter. The year-old group is an attempt to empower artist communities to influence major museum collections. They chose Stark’s work because no LA museum owned her paintings, despite the fact that she has played an important role in the fabric of the city’s art community. Happily, the work will remain in the collection long after “Made in LA” has closed.

“Made in LA 2018” is on view until September 2 at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles.