On View

Keith Haring’s Art Has a Secret Language—Here’s How to Decode His Most Powerful Symbols

An exhibition at the Albertina in Vienna sheds new light on the meanings behind the late artist's graphic and highly personal visual language.

An exhibition at the Albertina in Vienna sheds new light on the meanings behind the late artist's graphic and highly personal visual language.

Kate Brown

If he was still alive, Keith Haring (1958-90) would be 60 this year. To mark the 30th anniversary of the US artist’s untimely death at age 31, the Albertina Museum in Vienna is surveying the artist’s work from a new perspective. “Keith Haring.The Alphabet” (on view until June 24) is giving center stage to the symbolism that Haring created, revealing the sources that inspired the former street artist who studied semiotics while at the School of Visual Arts in New York.

Egyptian hieroglyphics were an important source of inspiration for Haring’s visual language, according to the Albertina. His pictorial vocabulary is being brought to the fore for the first time at the Austrian museum, where 100 works by the artist are on view.

“I am intrigued with the shapes people choose as their symbols to create language.” Haring said. “There is within all forms a basic structure, an indication of the entire object with a minimum of lines, that becomes a symbol. This is common to all languages, all people, all times.”

In the alphabet of picture-words he developed, each recurring image carries its own set of meanings. Some we already know well, such as Haring’s “radiant baby,” which is a symbol of the future and perfection. Others are just as prevalent but still not completely understood.

Here are some of the most fascinating meanings behind Haring’s personal and politically charged art alphabet.

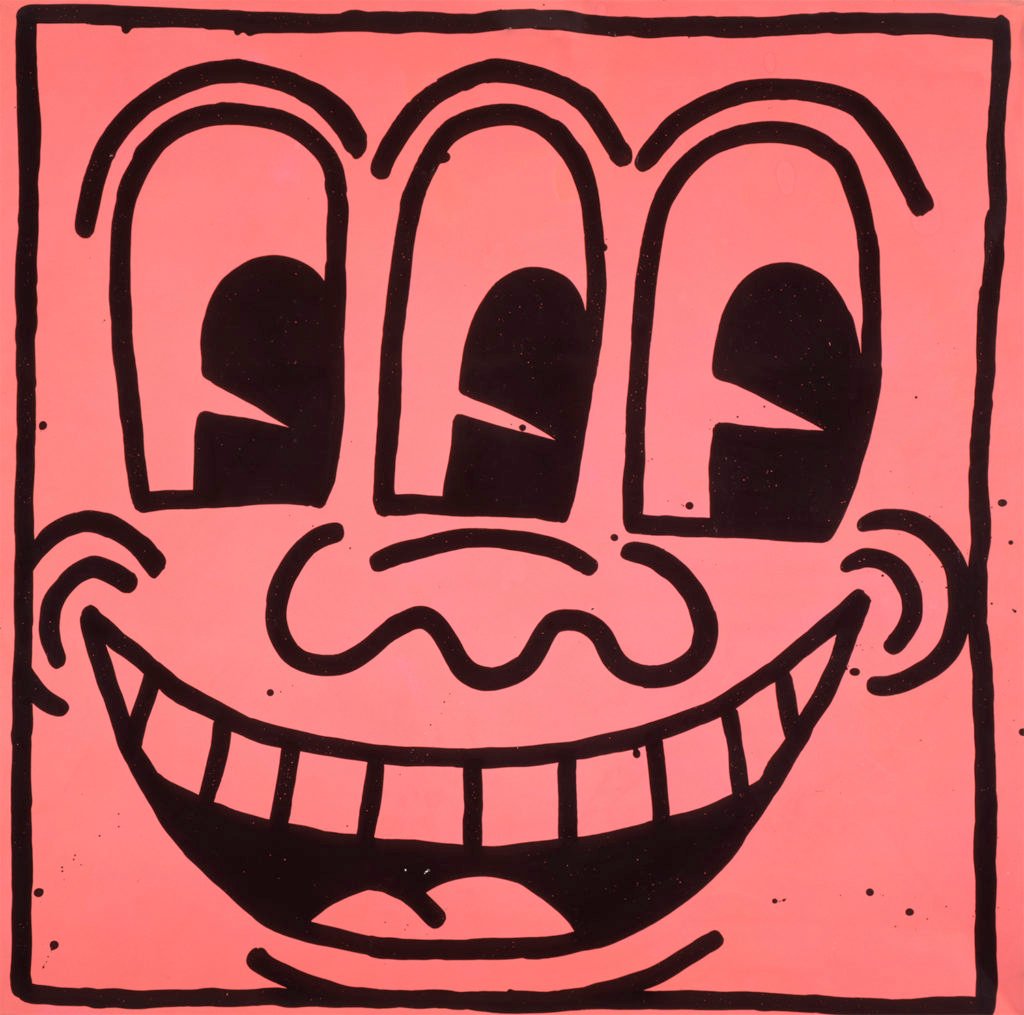

Keith Haring Untitled, (1981) Courtesy of The Brant Foundation, Greenwich, Connecticut, USA. © The Keith Haring Foundation.

In Haring’s ouevre, crowds conveyed an image of strength but they could be a negative or a positive phenomenon. In some cases, the crowd was depicted as a powerful and invincible united front against oppression. Haring explained that seeing the Vietnam War and race riots on television at the impressionable age of 10 years old had a huge affect on his political and social concerns. To Haring, the crowd could also represent a mob that could be easily led astray by false gods or dictators. He was aware of horrors such as the Jonestown massacre in 1978, when more than 900 people committed mass suicide led by the cult’s leader, Jim Jones. The image of crowds also reference tragedy and murder in Haring’s work.

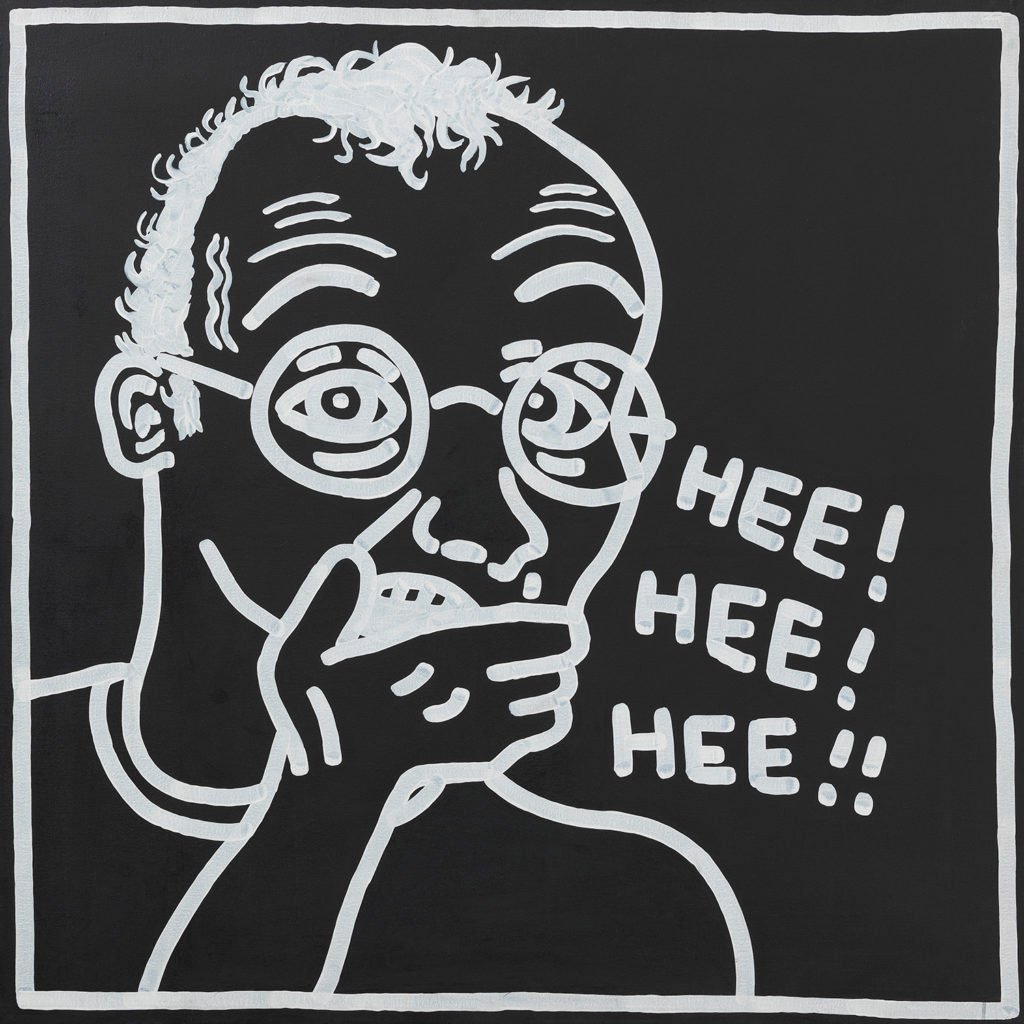

Keith Haring Untitled (1989). © The Keith Haring Foundation.

Keith Haring Untitled (1985) Private collection. © The Keith Haring Foundation

Haring was grew up in a religious family, and the connotations of the cross throughout his works are the subject of debate. Haring rejected fundamentalist Christianity and all dogmas, and his work is critical of the way the church could suppress its population. The crosses are sometimes pictured on screens, and they are often used as a device to commit torture or murder, with others standing by. Whether he rejected his upbringing or not, his biblical references show his knowledge of Christian stories, like the martyrdom of Saint Peter who was hung upside down on a cross.

Keith Haring Untitled (1984). Private collection, courtesy of Skarstedt Gallery © The Keith Haring Foundation.

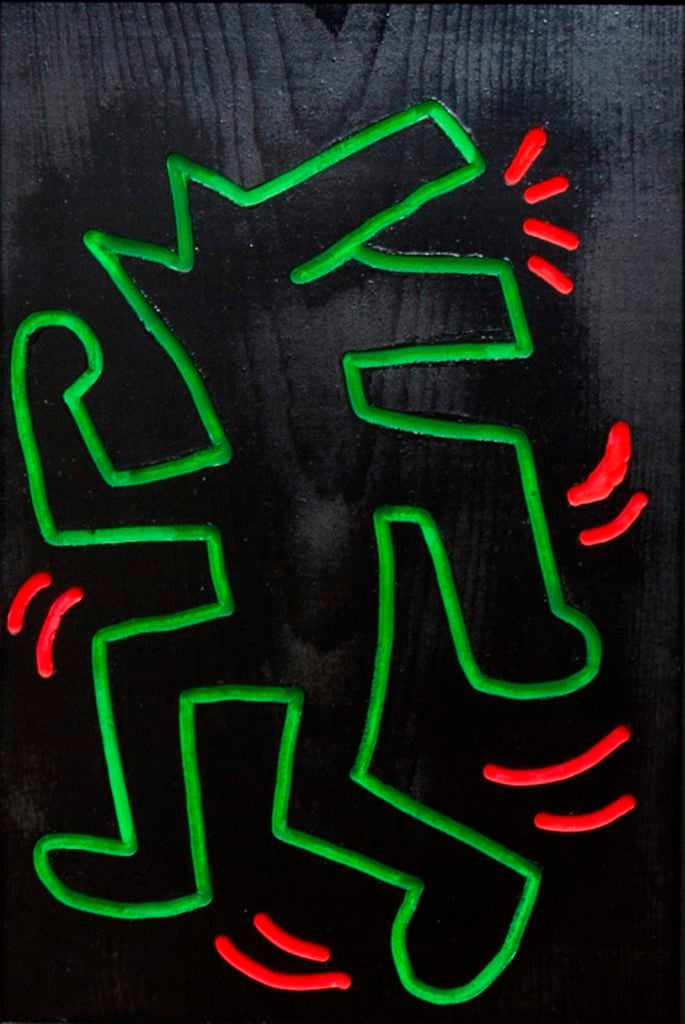

Dogs dancing, barking or biting recurred frequently within Haring’s work and developed into an iconic image associated with the artist. What later became a dog actually started out as an undefined creature, and Haring’s dog (often depicted on two feet) can best be understood as a mythical representation of a human being.

Dancing dogs often referenced artistic performance or breakdancing, but Haring’s dogs also stood for Anubis, the Ancient Egyptian god with a jackals’ head who watches over the dead.

In Haring’s versions, the image of dogs playing with or crushing small human figures plays into both these Egyptian conceptions of life and death, but also the Christian idea of the “dance of the dead.”

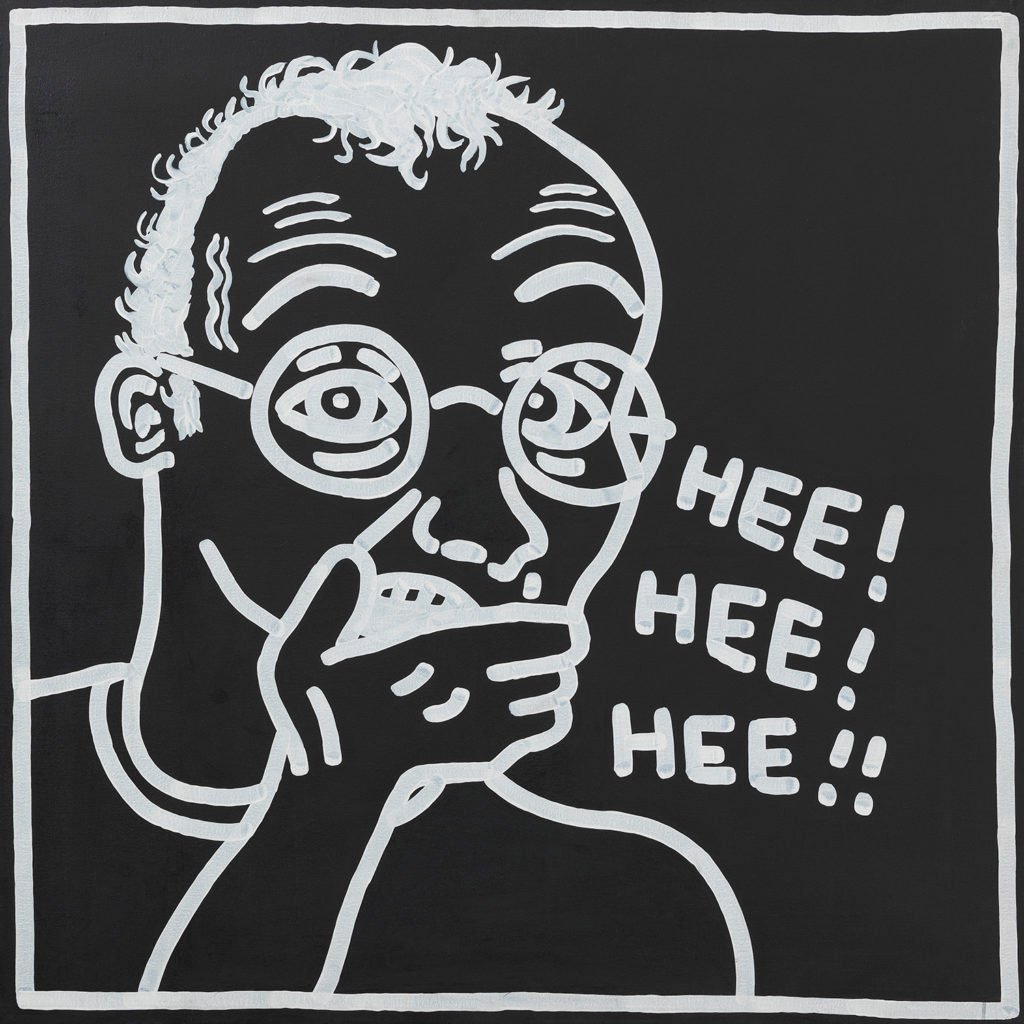

Keith Haring Untitled. (1983). Gerald Hartinger Fine Arts, Vienna. © The Keith Haring Foundation.

Keith Haring Untitled (1982). © The Keith Haring Foundation

Keith Haring Untitled, (1980).© The Keith Haring Foundation.

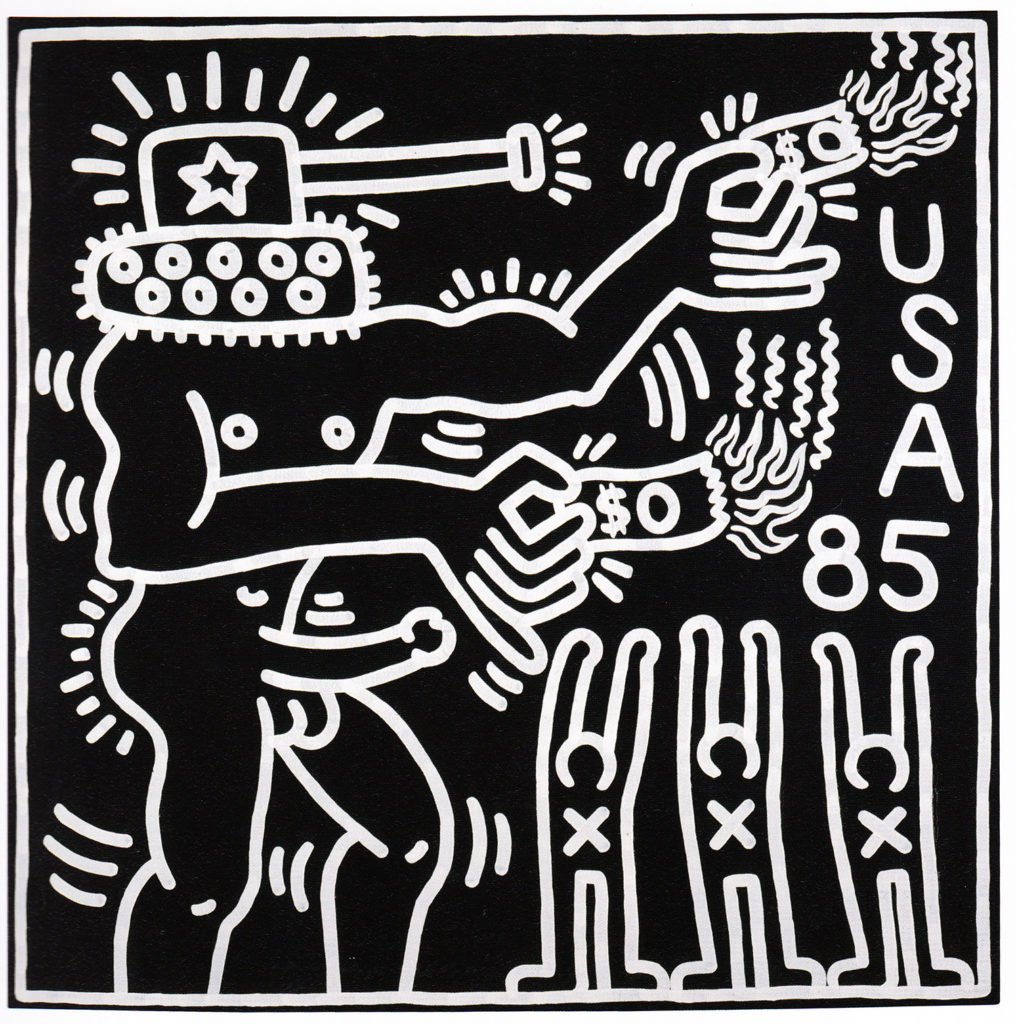

In Haring’s work the stick was a commonly drawn weapon, chosen as the most basic and readily available way to beat, torture or murder. It was also a source of power, imbued with magic and away to activate creatures, people, and objects in his works with strength.

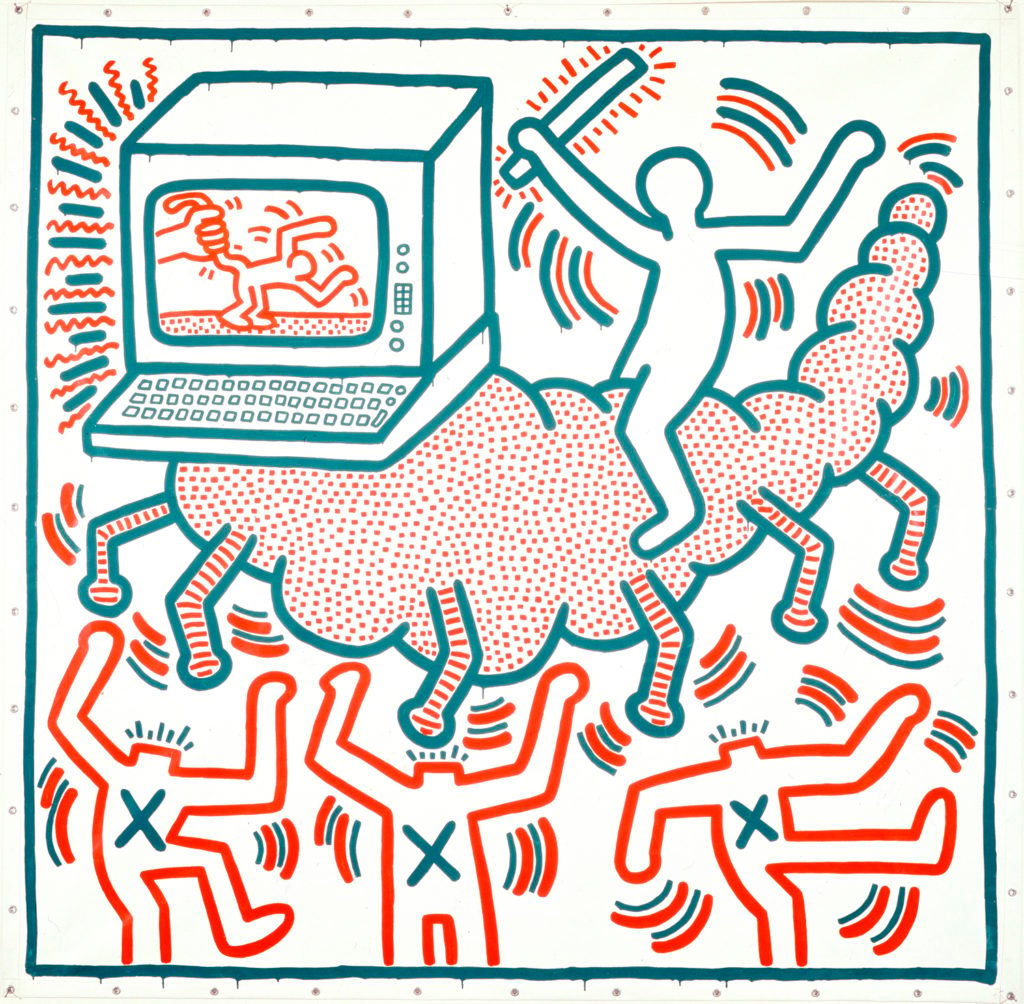

Haring had ambivalent feeling towards technology including television, and computers, robots or space aged machines are often depicted as exerting control over humans. Haring predicted in 1978 that silicon chips and computers would become their own life form, transforming humans into being in servitude to the computer, and not the other way around.

In his 1983 Untitled work, the artist depicts a caterpillar with a personal computer for a head. The caterpillar represents the feeding stage in the creatures transformation into a butterfly, and it sometimes appears as a monster, representing gluttony and greed.

UFOs also represented otherness, and stood for persons who were outside of the social norms. Whereas other technologies were rather ambiguous to Haring, flying saucers were always positive and symbolized empowerment.

Keith Haring Untitled, (1980) © The Keith Haring Foundation.

Keith Haring Untitled (1983) Collection of KAWS. © The Keith Haring Foundation.

Haring symbolizes the emptiness with all of us, but the hole that he often included on his figures was initially a response to the murder of John Lennon by a crazed fan in 1980.

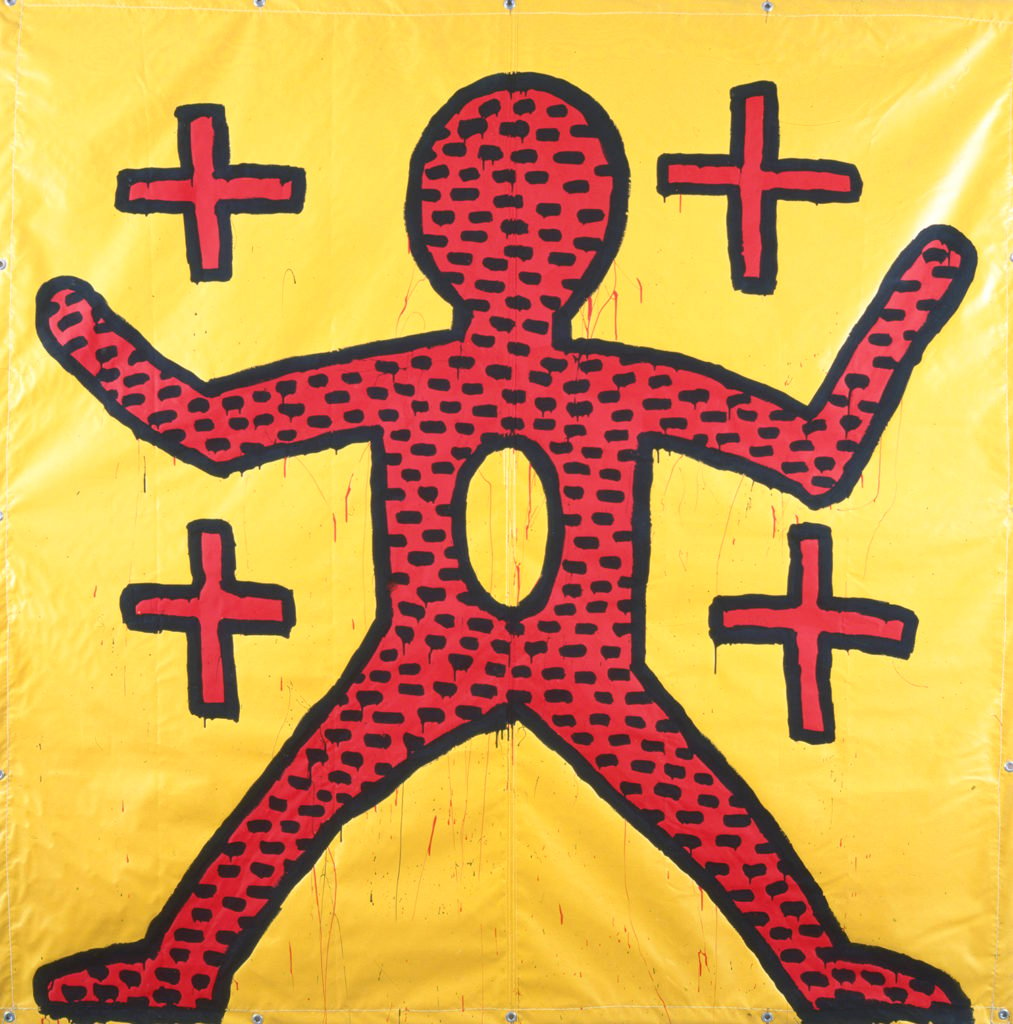

The “X” was a more general statement against the transformation of humans into targets. Sometimes beheaded or with their arms raised in a “don’t shoot” gesture, the artist takes a strong stand against events of the time, like the AIDS crisis, the state of emergency during the apartheid-era in South Africa, or the war in Vietnam war.

The dotted figure stands for otherness, including homosexality and skin color, both foremost political and social concerns for Haring. Later, dots also signified the otherness of illness, primarily AIDS.

Keith Haring Untitled, (1981). Museum der Moderne Salzburg, permanent loan from a private collection. © The Keith Haring Foundation.

Keith Haring Untitled (1982). Courtesy of Larry Warsh. © The Keith Haring Foundation.

Keith Haring Untitled (1985) Alona Kagan, USA. © The Keith Haring Foundation.

Keith Haring Untitled (1985). Courtesy of The Keith Haring Foundation, New York, and the Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels. © The Keith Haring Foundation.

Despite the violent imagery that is rampant in Haring’s work, his fundamental message was one of devout humanism and love. Take his recurring embrace, which is often between two genderless and race-less figures, who are glowing as they hold each other.

Keith Haring Untitled, (1982). Private collection. © The Keith Haring Foundation.