On View

‘Black Pain Is Not for Profit’: An Activist Collective Protests Luke Willis Thompson’s Turner Prize Nomination

The protesters accuse the artist of making work that profits from the suffering of black and marginalized people.

The protesters accuse the artist of making work that profits from the suffering of black and marginalized people.

Sarah Cascone

An artist is once again under fire for creating work in response to violence perpetrated against the black community. Demonstrators are targeting the Tate Britain to protest London-based artist Luke Willis Thompson, whose work is included in the annual Turner prize show at the museum.

This year, Thompson was nominated for the prize for his piece Autoportrait, a silent film portrait of Diamond Reynolds, the black women who live-streamed on Facebook the fatal police shooting of her partner, Philando Castile, in July 2016. The film is featured in the exhibition alongside two other works by Thompson, and the works of three other nominees.

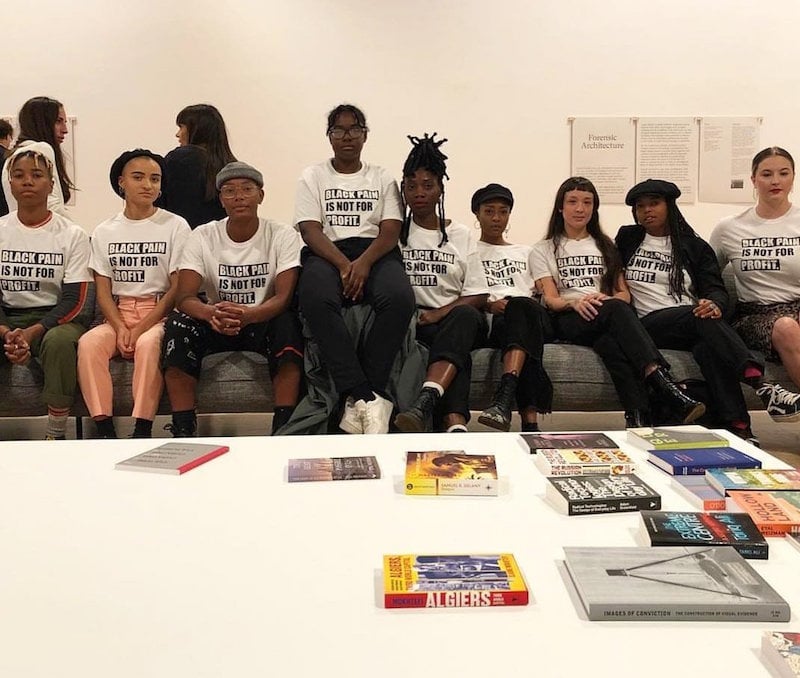

The protest at the Tate was organized by BBZ London, which describes itself on Instagram as a “curatorial collective from SE london, prioritising the experiences of Queer womxn, trans and nb poc [non-binary people of color].” In a post on the platform, the group wrote that it “decided to take a symbolic stand at the Turner prize opening, alongside members of a community of artists of colour, against the utilisation of black death and black pain by non-black artists and arts institutions for cultural and financial gain.”

In a statement emailed to artnet News, the Tate confirmed the demonstration. “A small group of visitors wearing identical t-shirts [reading ‘BLACK PAIN IS NOT FOR PROFIT’] sat on the sofas in the Turner Prize exhibition foyer,” a museum representative wrote. “They sat in silence for a few minutes and then left the gallery.”

The exhibition for the prestigious award, perhaps the art world’s best-known prize, opens tomorrow and features Naeem Mohaiemen, the interdisciplinary team Forensic Architecture, and Charlotte Prodger. For the first time ever, all four nominees are being recognized for work in film and video. It is the 34th edition of the Turner Prize, which celebrates the work of British artists with a £25,000 ($33,000) award.

Thompson, who is from New Zealand but lives in London, is of Fijian and European ancestry and identifies as a mixed-race person of color. Just 30 years old, the artist has made a name for himself with incisive work that addresses issues of racism, colonialism, and institutional violence. He has spoken of the parallels between the experiences of London’s black communities and those of Pacific descent in his native Auckland, but that has not insulated him from criticism.

Luke Willis Thompson. Image courtesy of the artist, courtesy Turner Prize.

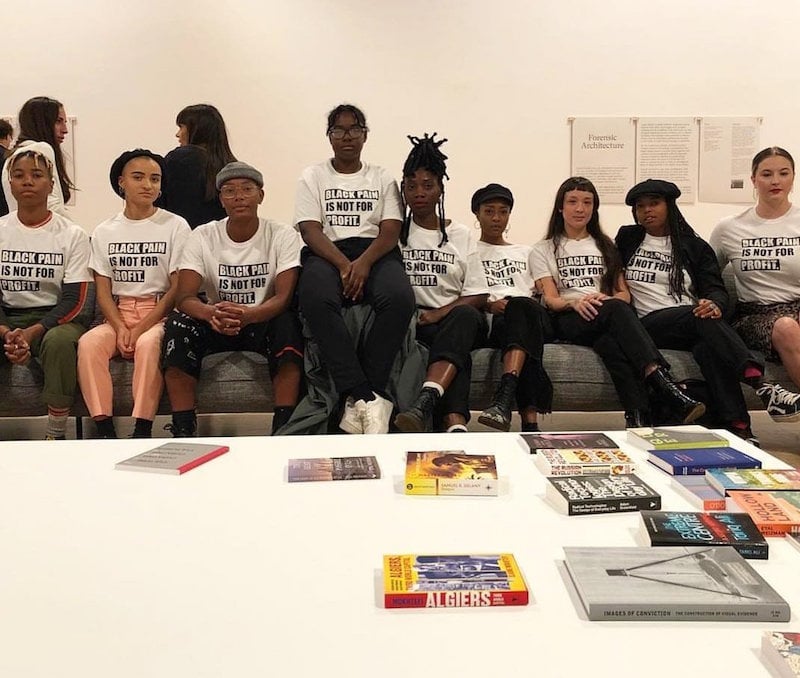

On Instagram, BBZ London shared an essay (also published on the magazine gal-dem) written by artist Rene Matić protesting both Thompson and his work. It begins, “I was on my way to university on Thursday morning when a tweet came to my attention. It read: ‘Luke Willis Thompson, a white [passing] man from New Zealand who self-identifies as black and therefore feels he is entitled to chase ambulances and make a spectacle of black death…all for his ‘art’…is nominated for the 2018 Turner Prize’.”

(The author of the original Tweet, the curator, researcher, and writer Rianna Jade Parker, has emphasized that she was not associated with the protest and that the Tweet was used without her knowledge. Thick/er Black Lines, a collective co-founded by Parker, has partnered on programming with the Tate.)

A screenshot of the Rianna Jade Parker Tweet cited by the protesters.

In her essay, Matić acknowledged Thompson’s Fijian heritage but argued that his fair skin gives him white privilege. “In short, Thompson is a white-passing male, making work and profiting off the violence and suffering of black and marginalized people,” she wrote. “Thompson’s work does not feel like a sensitive awareness-raising project, but a process of extraction, sensationalism and commodification.”

Autoportrait does not attempt to recreate the trauma of Castile’s shooting or ask Reynolds to tell her story. Instead, the artist’s goal was to collaborate with Reynolds on a simple portrait that honored her as a person.

Luke Willis Thompson, autoportrait featuring Diamond Reynolds (2017). Photo courtesy of the artist/Andy Keate.

Thompson told Radio NZ that he strove to portray Reynolds’s “dignity and clarity of mind,” adding that he had assured her that working with him “[would] be 100 percent on your terms.”

Reynolds and her lawyer had detailed conversations about the nature of the work ahead of its creation, Thompson explained to Noted, a New Zealand publication. “We talked about how an image is useful or not useful to their case, and how the media is useful and not useful,” he said, noting that the piece took six months to produce. “And we developed parameters for what was possible. What was possible was a silent film, because the biggest danger was that she says anything that then becomes testimony, or counter-testimony.”

The piece, conceived of as a “sister image” to Reynolds’s live stream, was made before Jeronimo Yanez, the officer who shot Castile, went to trial; Yanez was ultimately acquitted on all charges. The verdict was issued just days before Thompson unveiled Autoportrait at London’s Chisenhale Gallery in June 2017. The artist was named to the Turner Prize shortlist in April.

The controversy over Thompson’s work recalls the protests around Dana Schutz for her contribution to the 2017 Whitney Biennial in New York. Matić even points out the parallels between the two cases, citing artist Hannah Black’s open letter criticizing Schutz’s painting of the open casket of Emmett Till, an African American boy who was lynched after being falsely accused of flirting with a white woman.

For Matić, the issue goes beyond questions of whether or not it is appropriate for white artists to address issues of racism and race-based violence in their work. She would prefer black artists be allowed to speak for themselves, driving the discourse around race, rather than taking a backseat to successful white artists.

Luke Willis Thompson, Autoportrait (2017). Installation view, Chisenhale Gallery 2017. Commissioned by Chisenhale Gallery and produced in partnership with Create. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Andy Keate.

“Why do we need to focus on a white-passing man’s hot take on these issues?” Matić asked, questioning why black artists get criticized when they “‘make everything about race’ in our practices, yet artists like Thompson get lauded as artistic geniuses exploring the most ‘pressing political issues of today’?”

Critic Alex Quicho had a much different reaction to Thompson’s work. “Silver and luminescent, the film suggests timelessness. Reynolds’s posture spans history, with more than just the graceful turn of her head suggesting that of a saint’s,” she wrote in ArtReview. “Thompson’s film is thus doubly restorative, undoing the horror of the witness video while disqualifying the usual submission required of a portrait-sitter.”

Others see both sides. “I believe in Thompson’s intentions and admire his tactics, while remaining attuned to the discomfort that arises from him instrumentalising others’ trauma in ways that may benefit him as an artist,” wrote K. Emma Ng in the Pantograph Punch on September 26, 2017. “To my mind, these are not mutually exclusive.”

Thompson could not be reached for comment as of press time, but the Tate issued the following statement:

Luke Willis Thompson does not identify as white, he is originally from New Zealand, of Polynesian heritage and is mixed race. This trilogy of work by Luke Willis Thompson reflects his ongoing enquiry into questions of race, class and social inequality, which is informed by his own experience growing up as a mixed-race person in New Zealand. These films were made in the shadow of the Black Lives Matter movement and the artist sees his works as acts of solidarity with his subjects. He links his own position as a New Zealander of Fijian descent, treated as a person of colour in his home country, to that of other marginalised and disempowered communities. He finds ways of suggesting connections while also acknowledging the limits of what we can know of another’s pain, and how it can be represented.

“Turner Prize 2018” is on view at Tate Britain, Millbank, Westminster, London, September 26, 2018–January 6, 2019.