On View

‘Important and Timely’ or ‘the Ugliest Painting Ever Made’? How the Art World Is Parsing Nate Lowman’s New Show at David Zwirner London

The show marks the artist's debut at the mega-gallery.

The show marks the artist's debut at the mega-gallery.

Nate Freeman

On October 1, 2017, I took a flight from Kennedy airport to Heathrow to attend Frieze London, slept intermittently on the flight, and when I landed the next morning, I reached for my iPhone to swipe off airplane mode. Collectively, alongside my jet-lagged travelers, news alerts streamed in that, a few hours earlier, a gunman had used 14 semi-automatic rifles equipped with bump stocks and eight AR-10 battle rifles to murder 58 people at a music festival in Las Vegas. He sprayed bullets into the crowd from a perch in a suite at the Mandalay Bay Hotel. It was the deadliest mass shooting in American history.

Two years later, I took the same flight and, a few hours after landing yesterday, I went to David Zwirner’s London gallery to be among the first to see new paintings by Nate Lowman—work that grapples with that very massacre in a show that opens the two-year anniversary. It’s also Lowman’s first show with the global mega-gallery, having joined its prestigious roster earlier this year. When I arrived, Lowman was standing in the center of the gallery, hands brushing back his thick gray-gone-white shock of hair, as he led Zwirner himself and a handful of top gallery directors through the show.

The stakes could not be higher for Lowman. Long a market-friendly artist who has been embraced by the fair-going demimonde but not by brow-furrowing critics, Lowman is entering into his mid-career phase with a hell of a high-profile opening slot. The October show at Zwirner’s London space—in an exquisite townhouse on tony Dover Street in Mayfair—is a coveted one for its coincidence with Frieze. Last year at this time Zwirner held the first gallery show of new work by Kerry James Marshall in four years, and the first since he became the world’s most expensive living black artist.

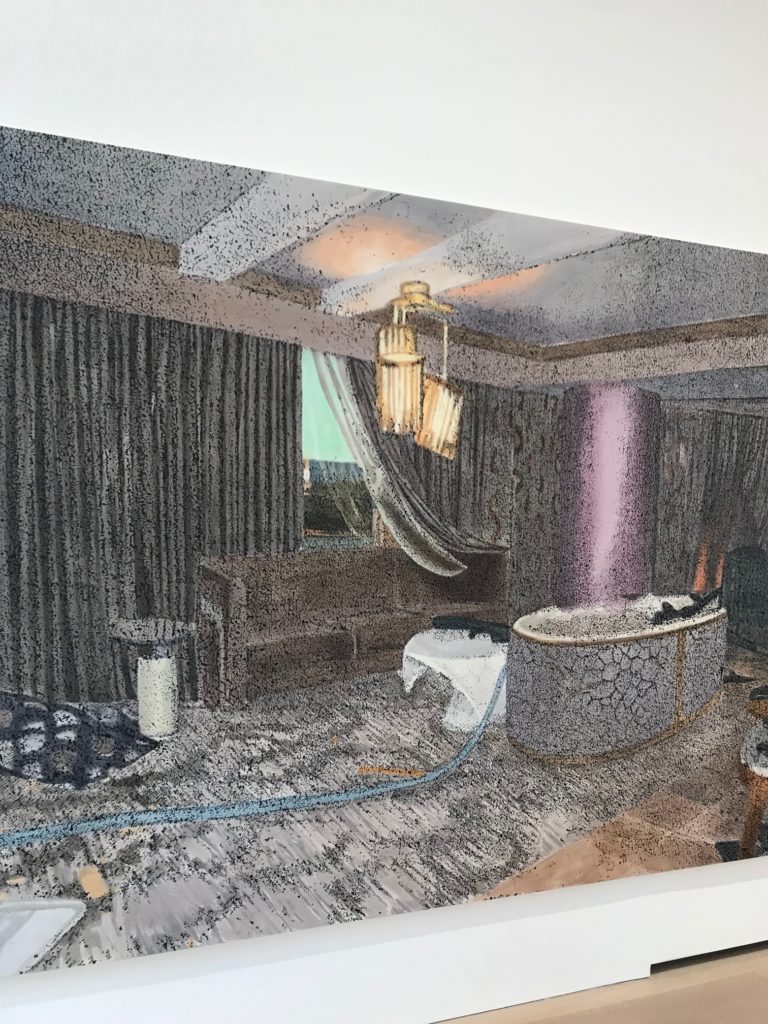

Installation view of “Nate Lowman: October 1, 2017” at David Zwirner. Photo by Nate Freeman.

The show is titled “October 1, 2017,” a reference to the date of the mass shooting in Las Vegas. There are 16 paintings, all rendering crime-scene photos of the shooter’s hotel room in the Mandalay Bay. They are each named according to the police investigators’ own titles for the images—Picture 23 (2019), Picture 11 (2019), etc. The paintings are, like some past Lowman work, pointillist by technique, so the set pieces for bloodshed appear fragmented when seen face-to-face, the dots and black marks made by applying a mix of oil- and alkyd-based paints to linen.

When you step back far enough, they show large guns strewn on the beds and floors, overturned tables, ammo, as well as the generic hotel-suite artwork on the wall. The killer and his act are never shown, but the menace is overwhelming.

“If you read true crime books and reports you know that everything is in the details,” Lowman said. “And of course, in this situation, the details are so chaotic and violent they’re almost impossible to approach.”

In several of the works the details appear innocuous at first, then chill to the bone. A blue L-bracket on a door turns out to be a handmade hurdle added by the killer to keep anyone from entering the suite once he opened fire. On a piece of pink index paper he’d written some numbers that, when inspected, are the distance in yards that bullets travel and the angles at which the gun needs to be pointed in order to hit the most bodies. In the end, 851 people were injured in the attack.

Lowman walked over to a painting that depicted a more mysterious item, a hose that had at its end the mouthpiece of a snorkel. “If you’re shooting so many bullets, it creates an enormous amount of gun smoke, and that hose leads to the source of not-smoky air, so he could breathe while he was doing this,” Lowman said.

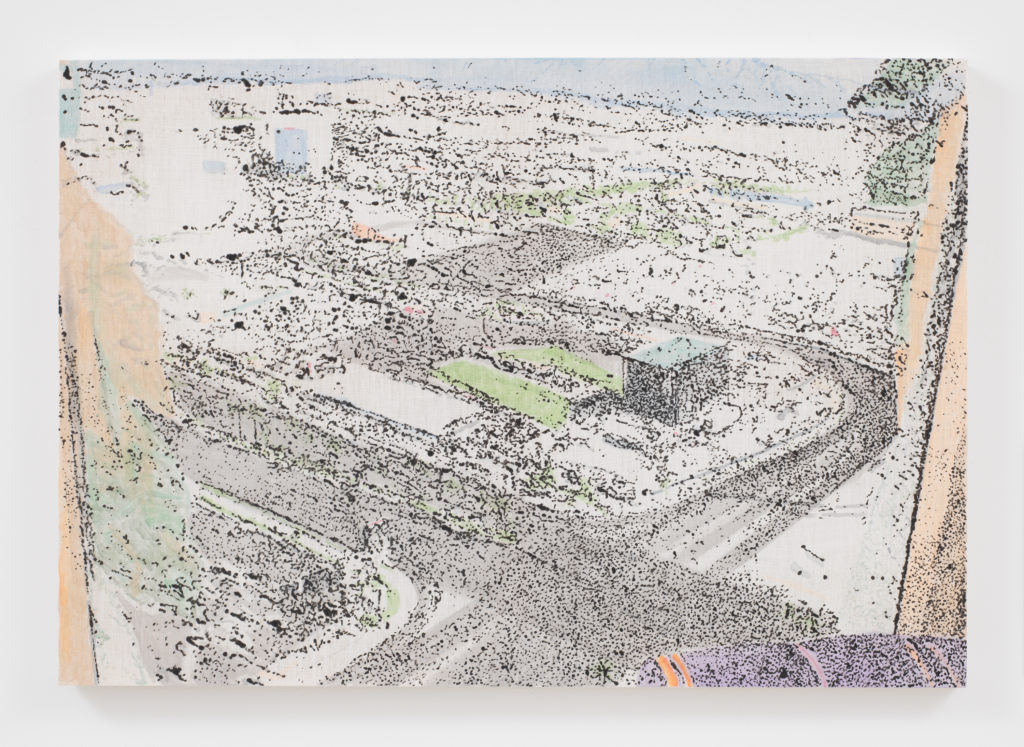

One painting appears, at a distance, to be an abstract white-on-blue Color Field work. In fact, it’s an oil tanker that was sprayed by gun residue due to the shooting.

Installation view of “Nate Lowman: October 1, 2017” at David Zwirner. Photo by Nate Freeman.

“This is a fuel tank, and this is at the McCarran airport,” said Lowman, who is from Las Vegas. “If you land in Las Vegas at McCarran airport—which is where you land if you fly to Las Vegas—depending on which side you’re sitting on, when you’re looking out what you see is the Mandalay Bay directly, and there’s this low expanse in between, and part of that in-between-space is where the music festival is happening.”

Growing up in Sin City was pivotal to establishing Lowman’s vocabulary, as it infused into his system a healthy dose of the dark runoff of the American dream—sex bought and sold, fortunes lost on the card tables, singers slumming it in casino residencies, buildings built and destroyed in the desert, gangsters killed for money. More than anything, his oeuvre reflects the country’s insatiable taste for violence, sex, and celebrity.

Lowman’s handle on such subjects propelled him to fame in his late 20s alongside his fellow enfant terribles Dan Colen, Ryan McGinley, and Dash Snow, and while his work is collected deeply by heavyweight museum-builders such as Steven A. Cohen and the Marciano brothers (as well as, um, Ivanka Trump), he has yet to become an artist that is taken seriously by the cognoscenti. He’s been profiled by the New York Times Styles section, but not the New York Times Arts section. A 2013 review in the New York Observer said of Lowman’s show at the private museum owned by the billionaire paper magnate Peter Brant, “Much bland, derivative art has been buoyed by the surging market in recent years, but little of it is as painfully lazy as Mr. Lowman’s.”

Nate Lowman, Picture 28

(2018). Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner; ©Nate Lowman.

And since 2015, his auction prices have receded—and then plateaued. After a one-off exhibition with Gagosian in 2018, he instead signed with arch-rival Zwirner, perhaps intent that he could sell at mega-gallery price points but be taken seriously as a mid-career artist. David Zwirner said in a statement that Lowman was “an artist whose career I have been following with interest for many years.”

“His critical engagement with contemporary culture as much as with art history is evident in his strikingly relevant works,” Zwirner said.

In London, the prices for work in the show ranges between $180,000 and $350,000, depending on the size of the work. These are roughly the same price points as the show at Gagosian, where Lowman showed his giant drop-cloth “Maps”—according to several advisors who asked not to be named—but well below his top lot at auction. That was achieved in 2014, when one of his “Marilyn” works—interpretations of Willem de Kooning’s Marilyn Monroe (1954), which proved to be trophy items for big-game-hunter collectors—sold at Phillips in London for $871,100. But four years later, in November 2018, another “Marilyn” that was slightly smaller than the 2014 record-breaker sold for just $200,000.

Directors at Zwirner did not immediately respond to questions about sales of the works at the gallery.

The show doesn’t technically open until Wednesday, but there’s been much chatter about whether or not the paintings have been selling. One advisor said that, while he enjoyed it, he wasn’t able to place the works with any clients. Another found it cynical and exploitative; a third said it was the best show in London. The anonymous Instagram account @whatanartshole said Picture 19 “may be the ugliest painting ever made by anyone” and described the show as “ever-perfect murder-porn for the super rich to help them feel ‘woke.’” Art advisor Meredith Darrow said that she didn’t feel any connection to the images when she looked at the PDF, but was convinced of their greatness when she saw them in person. One of her biggest clients, the Miami-based collectors Rosa and Carlos de la Cruz, purchased one painting.

“We have an extensive collection of Nate Lowman’s works dating back to his early pieces,” the de la Cruzes said jointly in a text. “We feel that it is a strong addition to our collection. This is an important and timely body of work that continues to critically engage issues of American culture.”

Nate Lowman, Picture 10

(2019), detail. Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner; ©Nate Lowman.

When I returned to the gallery the next day, it was crawling with local and out-of-town collectors despite being technically closed, and they walked slowly through the show, poring over the renderings of images of the haunted room muttering “Oh my God” to themselves as they took in the violence. David Zwirner himself was there to greet each one as they came down the stairs.

The paintings did look more arresting in person than I remembered—thematically horrifying, but possessing an almost lurid amount of beauty.

As for their legacy, it’s hard to say. During his talk to gallery visitors, Lowman admitted that, regardless of how much the show succeeds in highlighting gun violence in America, it will not help solve the crime. Two years later, investigators have yet to find a motive as to why the shooter, who killed himself after the slaughter, felt the need to commit such an act.

“We’re at a loss,” Lowman said.

“Nate Lowman: October 1, 2017” will be on view at David Zwirner, 24 Grafton Street, London, October 3–November 9, 2019.