On View

The Arrows Mean Death: A New Show of Paul Klee’s Wartime Paintings Reveals the Beloved Artist’s Dark Side

A show of more than 100 works by Swiss-German Surrealist Paul Klee shows the blood and gore behind his oeuvre.

A show of more than 100 works by Swiss-German Surrealist Paul Klee shows the blood and gore behind his oeuvre.

Eileen Kinsella

An exhibition of work by Paul Klee aims to reveal a darker side of the Swiss-German painter. Currently on view at the Zentrum Paul Klee in Bern, Switzerland, “Klee in Wartime” features an array of often fantastical works informed by the artist’s experience during World War I.

“I always thought that the time during the first world war was so important for Klee’s development,” the Swiss museum’s chief curator Fabienne Eggelhôfer told artnet News. “It’s strange because even though he had to go to war, he always found the time to really work and evolve. It’s interesting to see how those two worlds go together.”

In the early 20th century, Klee was already well-established as a member of the avant-garde movement Der Blaue Reiter (Blue Rider), participating in numerous exhibitions in the years before the war. But the buzzing art scene came to an abrupt halt when conflict broke out in the summer of 1914. Klee’s friends and fellow Blue Rider artists, August Macke and Franz Marc, were killed in action in 1914 and 1916, respectively, and abstract pioneer Wassily Kandinsky temporarily fled back home to Russia.

Paul Klee, Farbige und graphische Winkel (1917). Courtesy Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern

Klee was drafted into the German army in 1916. Fortunately for him, he was not deployed to the front. Instead, he was posted to airfields far behind the lines where he was responsible for cash administration and painting aircraft with templates in the army’s air corps. Eggelhôfer, who conceived the idea for the Klee show, says she has long been fascinated by the artist’s continued artistic output during this period, as well as his ability “to keep this kind of ironic distance to what was happening during the war.”

The show consists of more than 130 works—including paintings, drawings, watercolors, prints, and even hand puppets—rooted in the Expressionist, Cubist, and Surrealist movements for which his oeuvre is known. Almost all are from the museum’s collection, including an original Kaiser helmet from a Bavarian regiment that was a gift from esteemed Swiss dealer Eberhard Kornfeld. Working with another German institution, the Dreiländermuseum in Loerrach, the Zentrum Paul Klee also obtained loans of materials the artist worked with during his time in uniform.

Eggelhôfer says the periods where Klee was physically separated from his family have proven to be particularly valuable for researchers: “He wrote a lot of postcards and letters to his wife [Bavarian pianist Lily Stumpf]. We know what he’s thinking because he explained to her how his military service was like playacting, with a sense of: ‘I’m just doing what they tell me to do, but I don’t really have anything to do with this.'”

If a sense of detachment offered the artist a kind of mental bunker in wartime, Klee was also extremely inventive during this period. He employed both imagery and materials from his military environment, including linen from airplane wings. “He became very interested in the material because, at the time, it was pretty difficult to get paper, so he began to work more with fabric and use the stencils—numbers and letters that each airplane had—to infuse his work with imagery,” Eggelhöfer says.

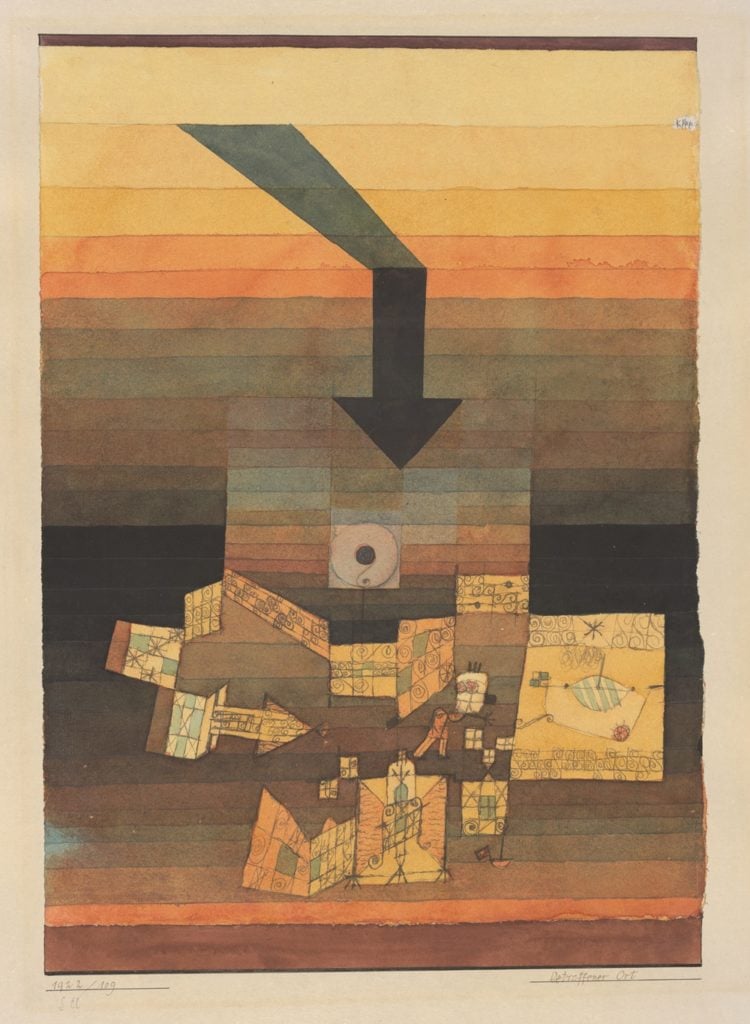

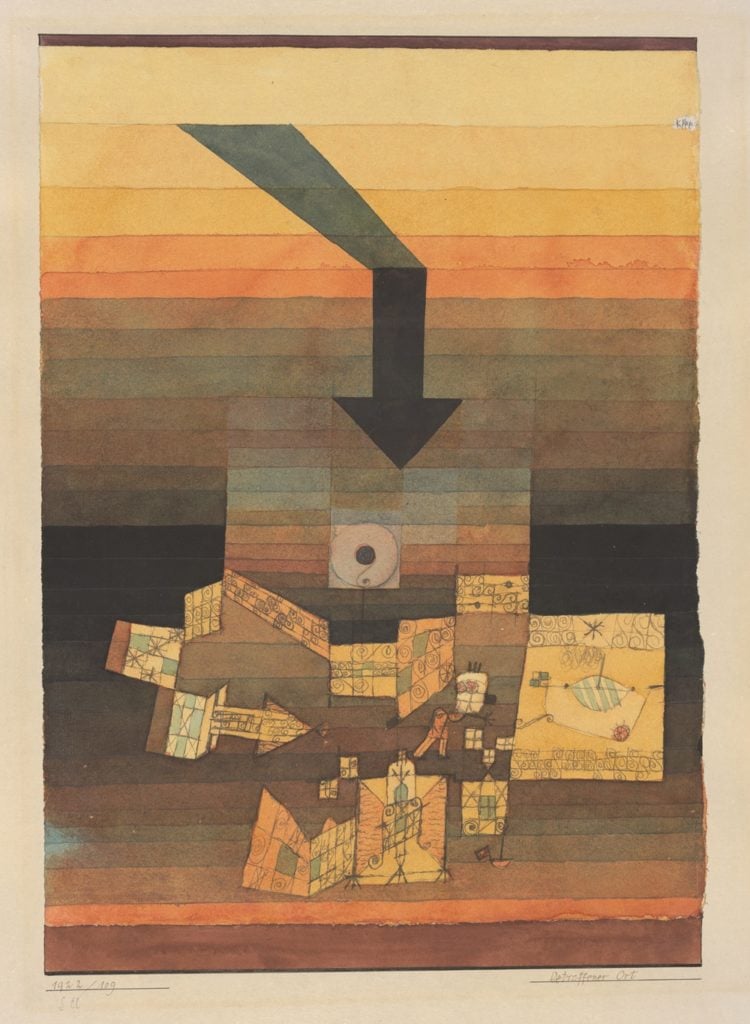

Klee’s abstractions also featured weapon-related imagery—such as arrows and exploding zigzags—that the curator says may have been lost on some audiences. The arrows reference “flechettes,” short steel rods with extremely sharp points and fins to facilitate speed. Used by various armies at the time, the brutal weapons—said to be able to easily pierce a steel helmet or human skull—were dropped en masse from planes into the trenches of enemy troops.

In 1917, a year before being discharged, Klee produced a series of works that included what he described as “angular zigzag movements.” The gestures were meant to express the oppression, fear, menace, and destruction wartime populations endured on a mass scale.

The artist’s financial returns may have had a hand in obscuring the true meaning of those symbols. According to background material on the show, Klee “repeatedly addressed the state of war in his works. But he was barely able to sell works like this from 1914 to 1915. This is probably one reason why Klee considered a more abstract pictorial language more appropriate to the expression of contemporary events.”

The approach appears to have paid off—at least in hindsight. Some of Klee’s highest sale prices are for works painted after the war, such as the auction record of $6.8 million paid for Tänzerin (1932), at Christie’s London in June 2011.

As for the works on view in Bern, Eggelhöfer hopes the exhibition will spotlight a deeper, lesser-known side of the artist. “People often think of Klee as a magician of sorts, who created his own sort of mystical dream world,” Eggelhöfer says. “But he was commenting on politics, society and the reality of war and I wanted to present that.”

“Klee in Wartime” is on view at the Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern, Switzerland, through June 3, 2018.