On View

How—and Why—’The Dinner Party’ Became the Most Famous Feminist Artwork of All Time

1.5 million visitors have seen Judy Chicago's work at the Brooklyn Museum to date.

1.5 million visitors have seen Judy Chicago's work at the Brooklyn Museum to date.

Sarah Cascone

It’s not very often that a single work of art can sustain an entire museum show. Yet this fall alone, Judy Chicago’s monumental work of feminist art The Dinner Party is the subject of two shows: at the Brooklyn Museum and the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, DC. (It also saw a contemporary restaging at October’s Art Toronto fair from a group of women artists with a seven-course meal prepared by female chefs—and served by men.)

With the Brooklyn Museum looking to the end of its “Year of Yes,” which celebrates the 10th anniversary of the Sackler Center for Feminist Art, it is only fitting that it would take a closer look at the genesis of its centerpiece, The Dinner Party. Its exhibition “Roots of ‘The Dinner Party’: History in the Making” tirelessly explores every aspect of the work’s production, while at the National Museum of Women in the Arts, “Inside ‘The Dinner Party’ Studio” features panels of documentation that show step-by-step photos of the work.

It took nearly five years to realize Chicago’s massive triangular banquet table—48 feet long on each side—that celebrates the historical achievements of women in Western culture. It required the assistance of some 400 volunteers, many of whom specialized in forms of so-called “domestic labor” that were rarely acknowledged by the contemporary art world, such as china painting and needlework.

Underscoring Chicago’s ceaseless drive to complete the mammoth undertaking was one unshakable belief: “It was so clear there was a big audience and a big hunger for female-centered art,” she told the show’s curator, Carmen Hermo, in an interview conducted during the leadup to the show.

Her feminist art installation “Womanhouse,” staged in Los Angeles with Miriam Schapiro and their students in the CalArts Feminist Art Program in 1972, had been a huge hit. In 1976, she visited a china painting trade show in New Orleans and was shocked to find herself among no fewer than one million attendees.

“That sparked something in Judy,” Hermo told artnet News during a tour of the exhibition. “The art world was saying ‘no,’ but there were lines out the door.” Chicago set out to educate herself about woman-centric artistry, soon finding that the experts were eager to share their knowledge.

Chicago took to some art forms more readily than others. “I could neither stitch nor sew—but it turns out I had this incredible ability to design for needlework,” she has said. “I discovered this when I saw my paintings on fabric being translated into thread. I was blown away because I didn’t know I had that ability.”

Judy Chicago, Christina of Sweden (Great Ladies Series) (1973). Courtesy of the collection of Elizabeth A. Sackler.

She is quick to acknowledge the crucial contributions of others to the project. The names all those who worked on it were displayed at each stop on The Dinner Party tour, along with photographs of the most invaluable participants, such as project administrator Diane Gelon. They appear on view again at the Brooklyn Museum.

Also on view are Chicago’s notebooks—which show early sketches of the project that envision it as a female counterpart to the Last Supper with 13 figures—as well as preliminary versions of the ceramic plates (some took as many as 15 tries).

A celebration of female accomplishment, The Dinner Party operates on multiple levels. Not only does it set a place, literally, for unsung women in the pantheon of history, it also makes a powerful argument for the importance of these traditionally feminine artistic practices, which have been unfairly relegated to the realm of craft.

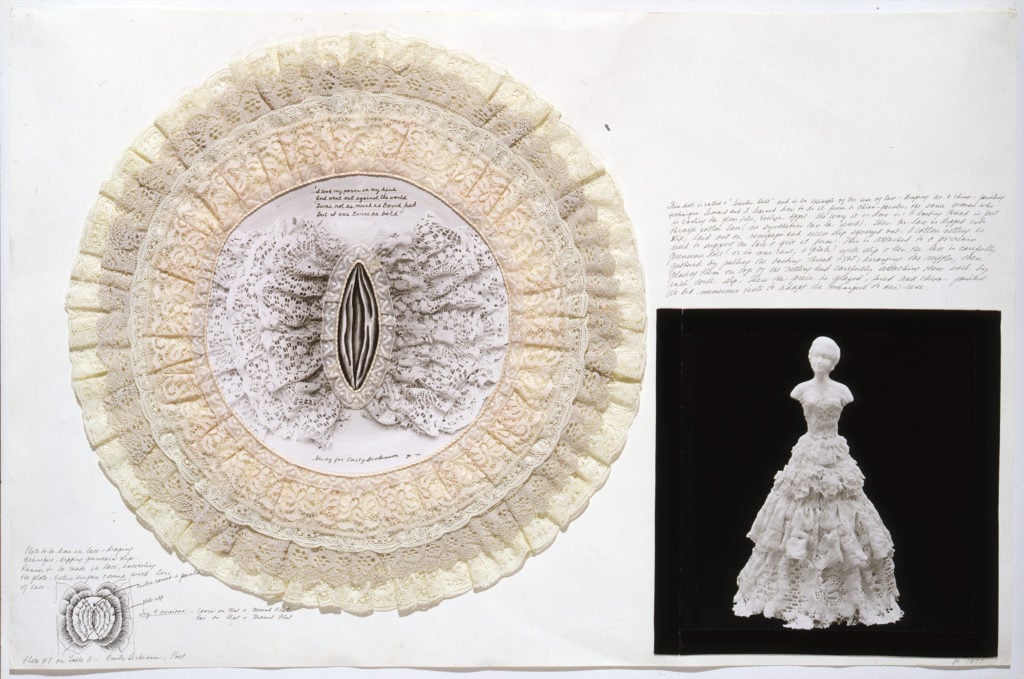

Judy Chicago, Study for Emily Dickinson from the Dinner Party, (1977). Courtesy of the National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, DC.

Perhaps most notably, The Dinner Party is a reclamation of the female anatomy. Celebrating the power and beauty of the vulva stood in contrast to the overwhelming dominance of the phallus in visual culture, all the way down to our city skylines.

This unrepentant vaginal iconography, the ceramic plates blossoming from a central form, was “a way of reclaiming the fact that women were degraded for their bodies, that being called a cunt was a terrible slur,” Hermo said. “Judy wanted to add power to what it meant to have a vagina.”

Unsurprisingly, not everyone approved. The Brooklyn Museum was one of only two US museums to welcome The Dinner Party during its inaugural 13-city international tour between 1979 and 1989. The first stop, at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, was the institution’s most-visited exhibition of all time, but backlash over the work’s overt vaginal imagery made other museums wary.

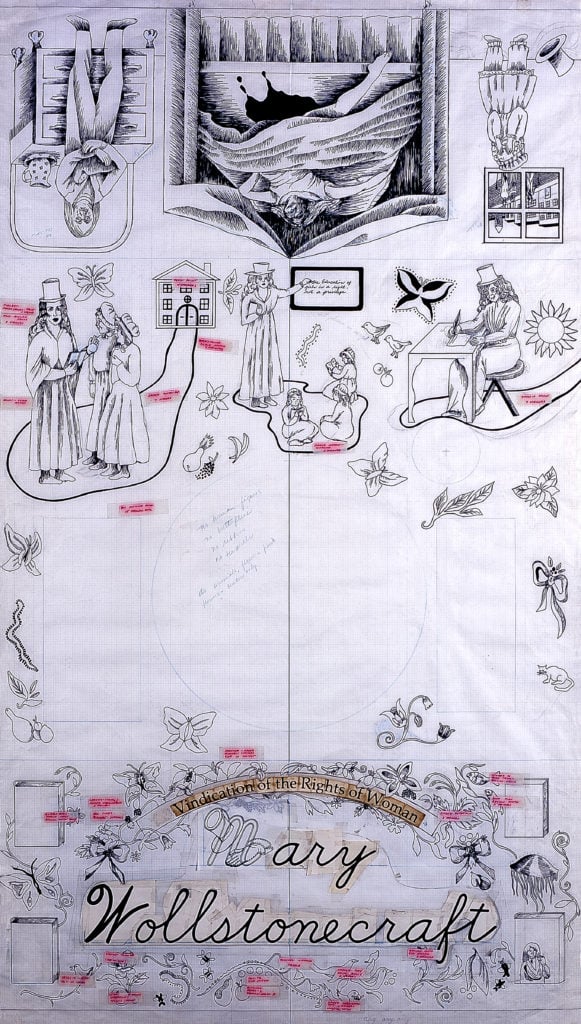

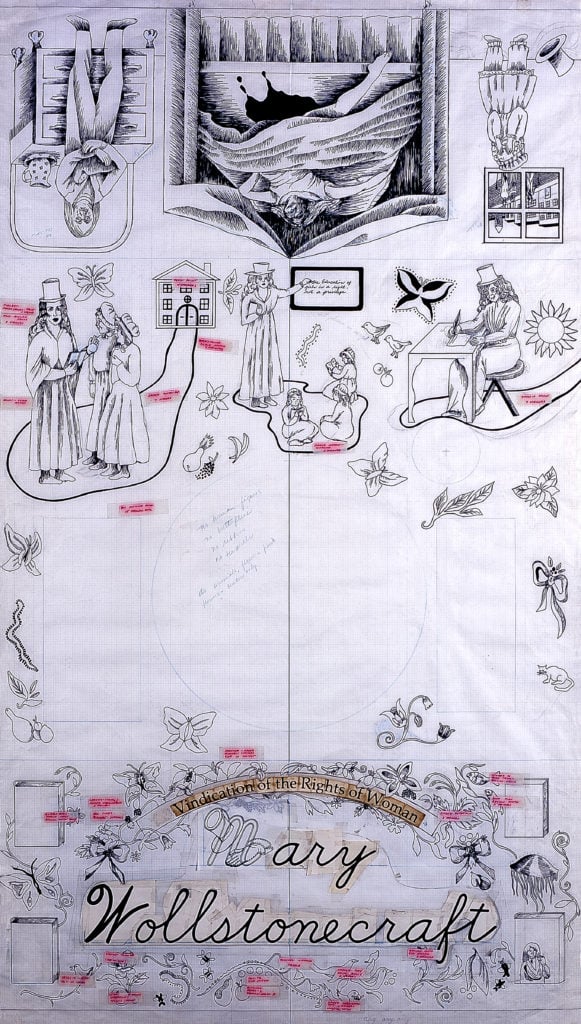

Mary Wollstonecraft Gridded Runner Drawing, from The Dinner Party (1975-78). Courtesy of the Lawrence B. Benenson Collection.

As a result, the tour was almost entirely crowd-funded, sometimes stopping, to Chicago’s chagrin, at gymnasiums and other awkward, non-institutional venues. Posters and advertisements, some of which appear in the Brooklyn Museum show, invite interested parties to “help the girls travel” with tiered donations noting how far your money would go—$5 covered the cost of the cutlery for one placesetting, for instance.

When the tour wrapped up, Chicago had hopes of finding her opus a permanent home at a museum, but The Dinner Party fell victim to the Culture Wars of the 1990s. Plans to donate it to the University of Washington, DC, fell through after a congressional hearing declined to approve the necessary federal funding. The Elizabeth A. Sackler Foundation acquired the work in 2002 and donated it to the Brooklyn Museum the same year.

A special exhibition of the piece in 2002 was followed by the opening of the Sackler Center five years later, with The Dinner Party as its centerpiece. On the occasion of the new show, the work has a new lighting system, making it easier to admire the richly detailed fabrics and ceramics while still meeting conservation needs. To date, some 1.5 million visitors have seen it at the Brooklyn Museum.

Chicago’s ambitious effort to rewrite the history books, inserting the achievements of forgotten women into the narrative, was complicated by the lack of existing sources. Remarkably, Chicago considered the names of some 3,000 women, before settling on the final 1,038, with 39 place settings and an additional 999 names inscribed in gold on the hand-cast porcelain tile Heritage Floor.

“The Dinner Party” Workers Painting Names on the Heritage Floor Tiles (1978). Courtesy of Through the Flower Archive.

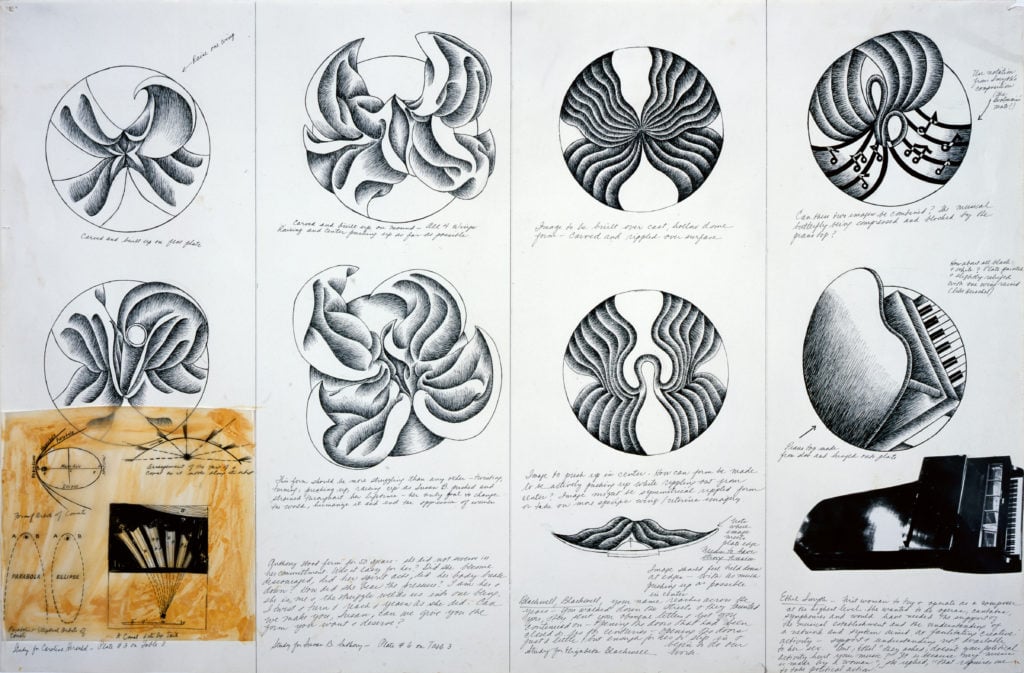

Among those immortalized with ceramic plates are ancient Greek poet Sappho, Benedictine abbess and writer Hildegard of Bingen, astronomer Caroline Herschel, women’s rights activist Susan B. Anthony, and painter Georgia O’Keeffe.

The show includes some of the obscure publications consulted during the project, such as John Maw Darton’s 1880 book Famous Girls Who Have Become Illustrious Women of Our Time: Forming Models for Imitation by the Young Women of England, and Mary Hays’s six-volume Female Biography, or Memoirs of Illustrious and Celebrated Women of All Ages and Countries. When The Dinner Party team borrowed the latter from the UCLA library, they discovered it hadn’t been checked out in 65 years.

“There was almost nothing available,” Chicago said. “We were literally making herstory.”

See more photos from the exhibition below.

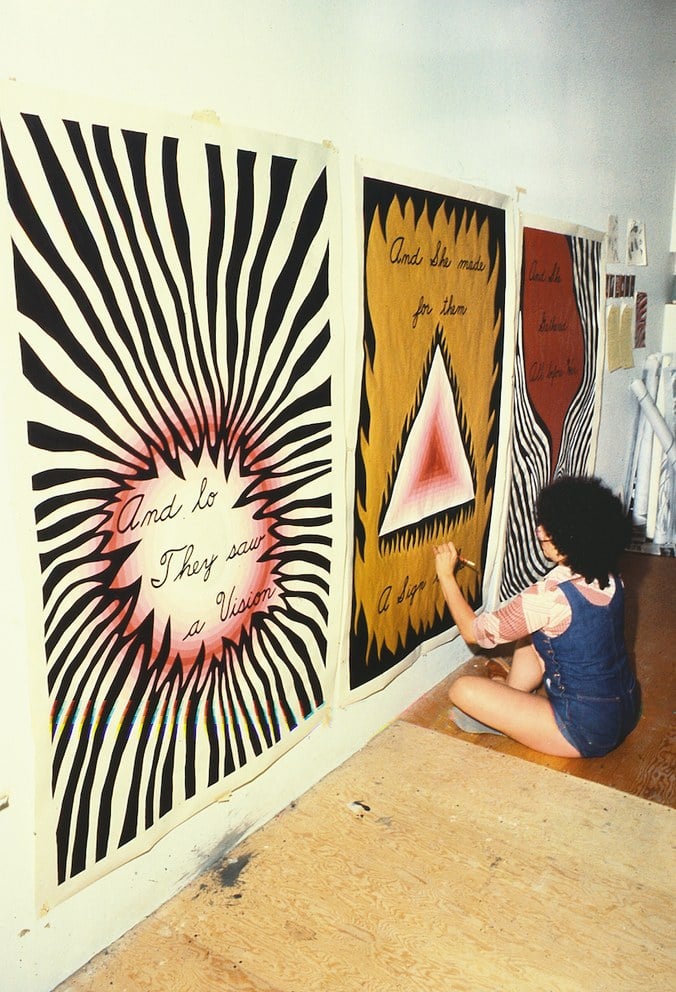

Judy Chicago designing the entry banners for The Dinner Party (1978).

Courtesy of Through the Flower Archive.

Judy Chicago, Study for Caroline Herschel, Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Blackwell, and Ethel Smyth plates, from The Dinner Party (1978). Courtesy of the artist and Salon 94, New York.

Mary Wollstonecraft Gridded Runner Drawing, from The Dinner Party (1975-78). Courtesy of the Lawrence B. Benenson Collection.

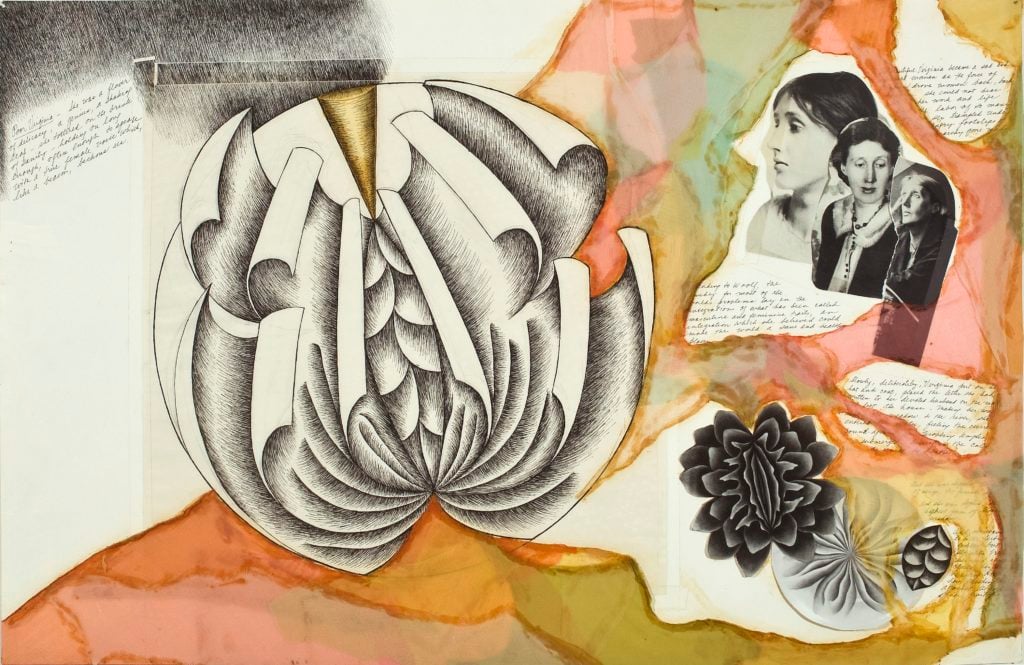

Judy Chicago, Study for Virginia Woolfe from The Dinner Party (1978). Courtesy of the National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, DC.

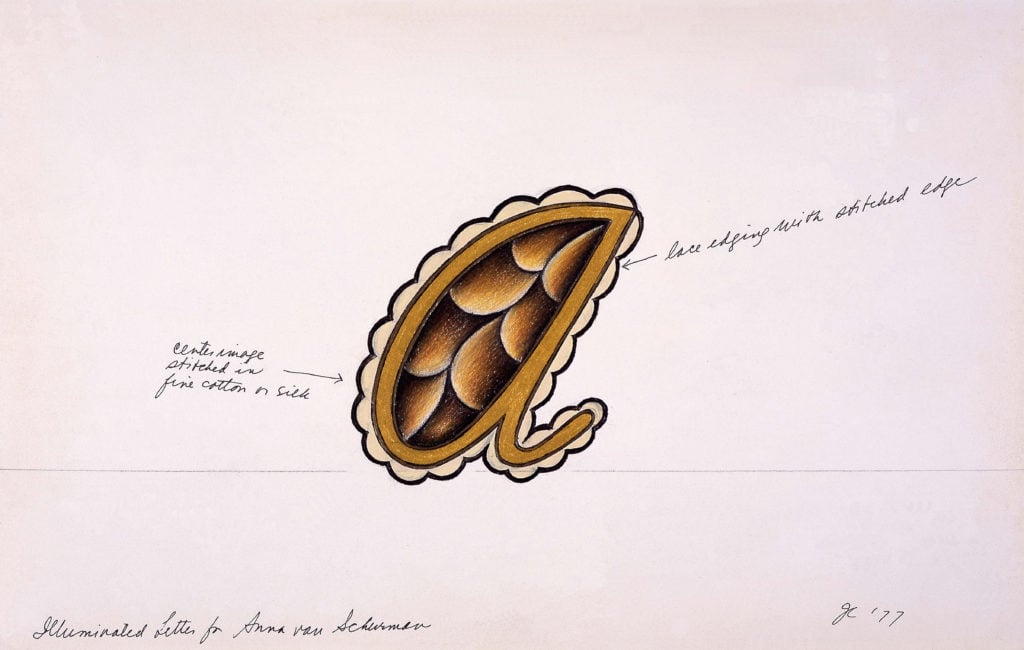

Judy Chicago, Illuminated Letter for Anna van Schurman (1977). Courtesy of the artist and Salon 94, New York.

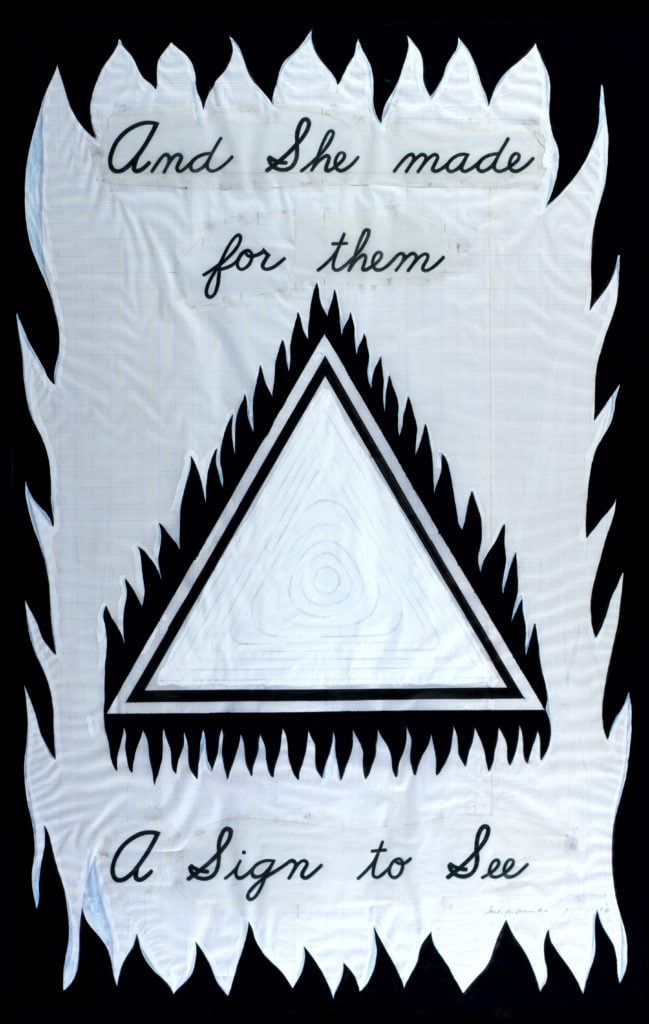

Judy Chicago, Cartoon for Entryway Banner #2 – And She Made for Them a Sign to See (1978). Courtesy of the artist and Salon 94, New York.

“Roots of ‘The Dinner Party’: History in the Making” is on view at the Brooklyn Museum, Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, 4th Floor, 200 Eastern Parkway, Brooklyn, October 20, 2017–March 4, 2018.

“Inside ‘The Dinner Party’ Studio” will be on view at the National Museum of Women in the Arts, Betty Boyd Dettre Library and Research Center, Dix Gallery, 4th Floor, 1250 New York Ave NW, Washington, DC, September 17, 2017–January 5, 2018.