Art & Exhibitions

The Winner of This Year’s Turner Prize Has Yet to Be Revealed, But the People’s Choice Is Clear

The audience is also rather grumpy this year, if the pinboard outside the exhibition is anything to go on.

The audience is also rather grumpy this year, if the pinboard outside the exhibition is anything to go on.

Naomi Rea

The Turner Prize hasn’t been awarded yet—that will happen on December 4. But as far as the public is concerned, the results are already in.

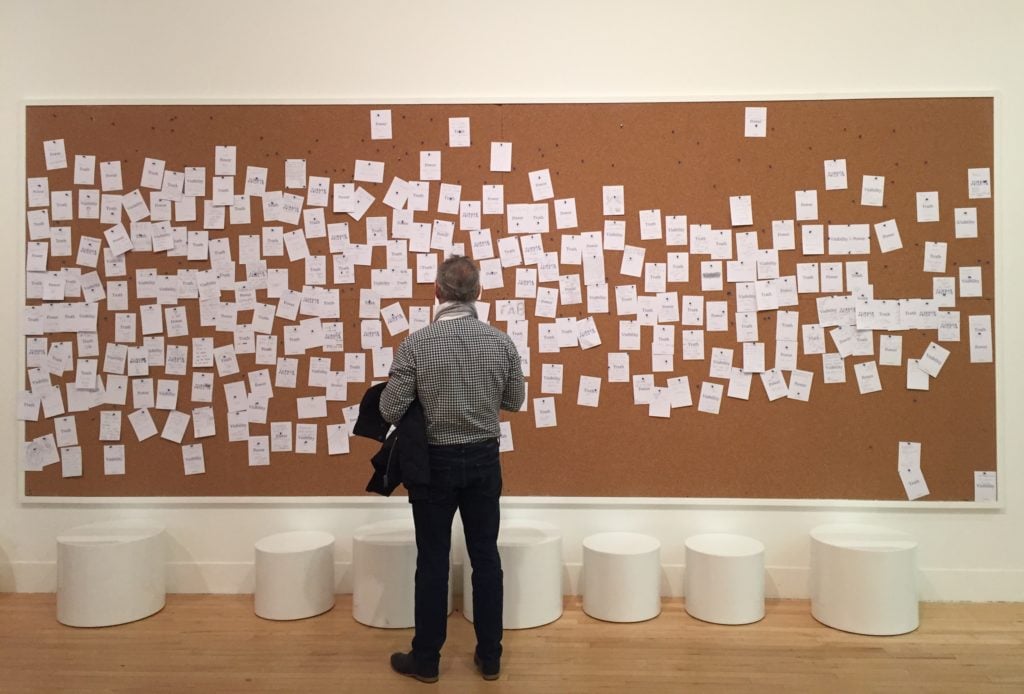

At the entrance to the Turner Prize exhibition at Tate Britain in London, you can’t miss the massive pinboard on which visitors have been posting their opinions since the show opened at the end of September. Featuring work by the UK-based artists and art collectives Forensic Architecture, Naeem Mohaiemen, Luke Willis Thompson, and Charlotte Prodger, the annual competition—now in its 34th year—seems to have struck a particularly tetchy nerve among museum-goers. It’s also clear, however, that one nominee has emerged as the crowd favorite.

To the museum’s credit, Tate has been collecting audience responses since the 2002 edition of the prestigious £25,000 ($33,000) prize show. This year, it invites people to reflect on three themes in the exhibition: power, visibility, and truth, and also encourages them to weigh in online.

Tate’s head of visitor experience, Eleanor Appleby, explains to artnet News that visitors “are free to respond in their own way to the exhibition” on the comment board and that, “only explicit or offensive content is removed, otherwise the cards are collected once the board is full.” At the end of the exhibition, a selection of comments is sent to the archive.

“One of the key roles of the Turner Prize is to promote discussion and debate around contemporary art so we encourage visitors to respond and engage with the exhibition as much as possible,” Appleby explains.

In the name of investigative crowdsourced art criticism, artnet News visited the message board in October and November, and this is what we discovered. If you filter through the unavoidable trolling—“Helen Marten should win,” or “bring back the bum!” (both referring to the 2016 crop of nominees)—and less art-centric complaints (such as the 82-year-old who found the dark conditions of the video installations “scary”), a few trends become clear.

The message board outside the Turner Prize Exhibition. Photo by Naomi Rea.

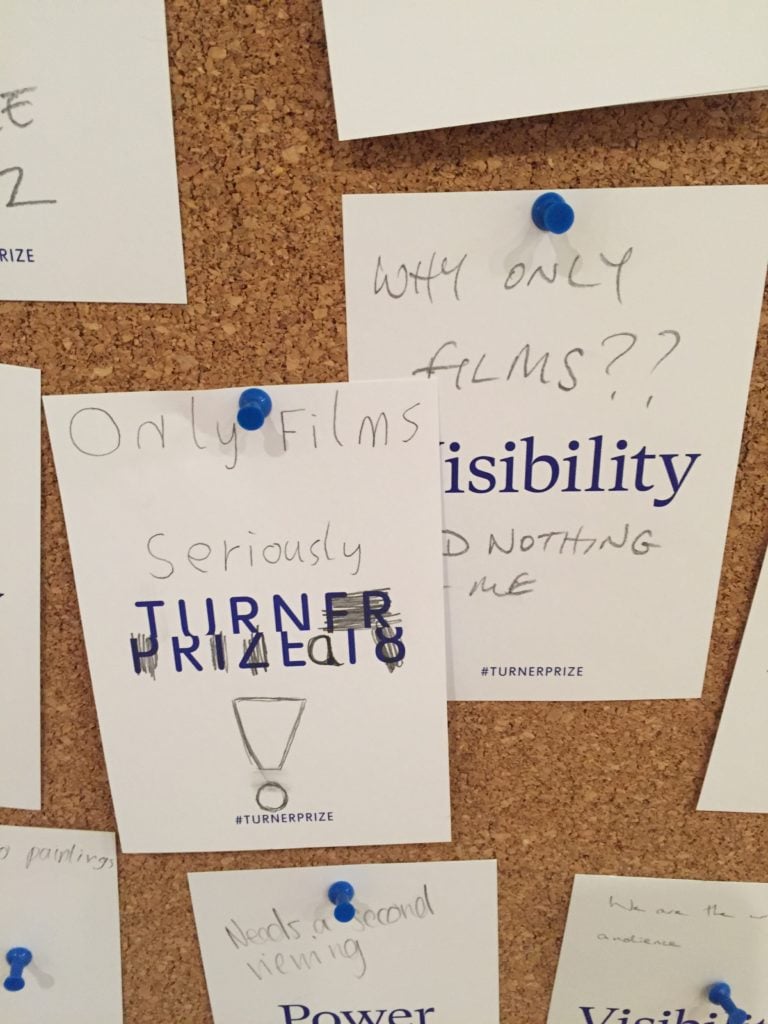

Overwhelmingly, people were negative about the fact that, for the first time ever, the show consists entirely of video works. (Tate estimates that it takes around four and a half hours to take in the whole exhibition.) The decision to leave out paintings, sculpture, and work of other kinds seems to have incensed many commentators. One visitor, who signs his name Adrian, wrote: “Worst Turner Prize show I’ve seen in all the years I’ve been visiting Tate. Why all videos? There must be creative artists using other media.” Another wrote that it was “very difficult to be enthusiastic” about the demanding work on show. There were a few, however, who defended the selection. “Video art is the future so stop asking where the paintings are,” one person scratched in pencil.

There was also a general grumble that the show is too political. The works variously address issues around migration, identity politics, and police violence. “Exploiting politics when you have no ideas,” was one viewer’s cynical summary.

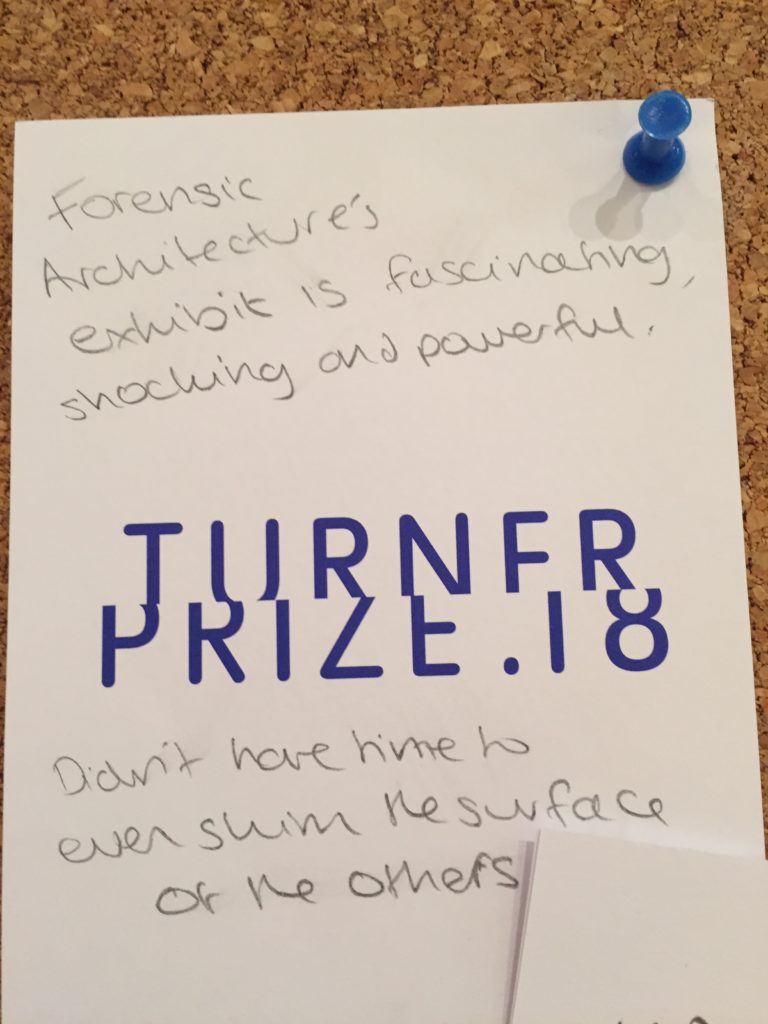

In all this, Forensic Architecture emerges as the clear popular choice. The team of architects, filmmakers, lawyers and scientists was nominated for the prize due to its powerful participation in documenta 14, among other presentations.

The collective’s work on view, The Long Duration of a Split Second, reconstructs a morning of violence in the Israeli desert. The installation centers around an early-morning eviction of the Bedouin village of Umm al-Hiran on January 18 of last year, which resulted in the death of a Bedouin villager and an Israeli policeman. Using audio and video footage collected from witnesses to the event, thermal imaging, and empirical science, the collective painstakingly puts forward an alternative version of what the Israeli government initially presented as a terror attack carried out by the villager.

The message board outside the Turner Prize Exhibition. Photo by Naomi Rea.

“So important to show collective activist work such as this,” reads one comment, adding, “Incredibly powerful.” Others called it “brave,” and “urgent,” and several noted that it was a standout presentation compared with the other candidates, with one commenter deeming the other three presentations “actual uncomfortable snoozefests” by comparison.

To be sure, it drew some criticism for its positioning on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Among several “free Palestine” comments were others more questioning of the conclusion that is drawn (that the villager was shot by police before losing control of his vehicle, which subsequently plowed into the officers), calling it “Palestinian propaganda.” But it also drew praise for engaging viewers in an inquiry as to the role of truth in an era of “fake news” and Donald Trump’s so-called “alternative facts.”

As always with the Turner Prize, a number of people were asking “is this art?” (some less politely than others). With Forensic Architecture, this becomes a more interesting question as the agents behind it all readily admit that, well, they’re not really artists.

Putting the philosophical questions this raises to one side, if we were to hazard a cynical guess as to why Forensic Architecture’s investigation emerged as the people’s favorite, we might think about the popular fascination with “true crime” documentaries. This grisly intrigue might be paired with the fact that the presentation, separated out into bite-size chunks, is easier to take in than, for example, either of Mohaiemen’s roughly 90-minute films.

For his part, Mohaiemen earned a couple of mentions in the comments, as did Charlotte Prodger. Luke Willis Thompson didn’t get a look in when we visited in November, which is somewhat surprising given the controversy generated by his work. The London-based, New Zealand artist was nominated for his piece Autoportrait, a silent film portrait of Diamond Reynolds, the black woman who used Facebook to livestream the fatal police shooting of her partner, Philando Castile, on July 2016. An activist collective, BBZ London, protested Thompson’s nomination back in September. Back in October, though, one of the comments read, “Luke Willis Thompson profits from racism. Don’t give him £££.”

For all that, the actual prizewinner will be selected by a jury, not the public. This year’s judges, presided over by Tate Britain director Alex Farquharson, comprises the art critic Oliver Basciano, Kunsthalle Basel director Elena Filipovic, Holt-Smithson Foundation executive director Lisa Le Feuvre, and the novelist Tom McCarthy.

“Turner Prize 2018” is on until January 6, 2019.