Art & Exhibitions

Walter Robinson’s First Solo Museum Survey Opens in Philadelphia

His photo-based paintings touch on both the banal and the mythic.

His photo-based paintings touch on both the banal and the mythic.

Brian Boucher

Barry Blinderman first laid eyes on Walter Robinson’s paintings 35 years ago, and he’s never forgotten that first encounter. The specific piece, Blinderman said Friday at the opening of a survey of Robinson’s work at the Galleries at Moore College of Art & Design, was Man with Bottle (1980), whose subject, in the midst of a bar brawl, wields a broken wine bottle.

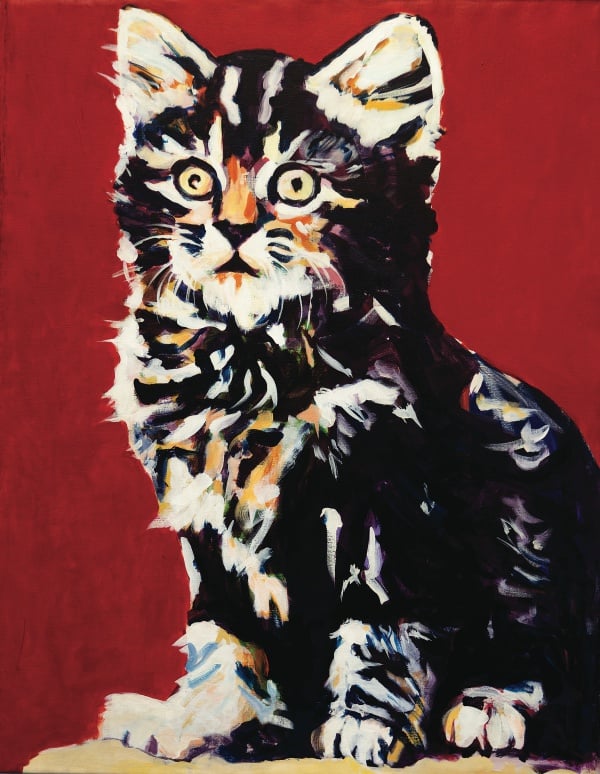

“He’s such a forceful painter,” said Blinderman, who curated the show. He was effusive about the artist, who is known for paintings of pulp fiction book covers, catalogue models, hamburgers, and the occasional kitten. “As banal as the subjects seem, they always ring bells on a personal and even mythic level.”

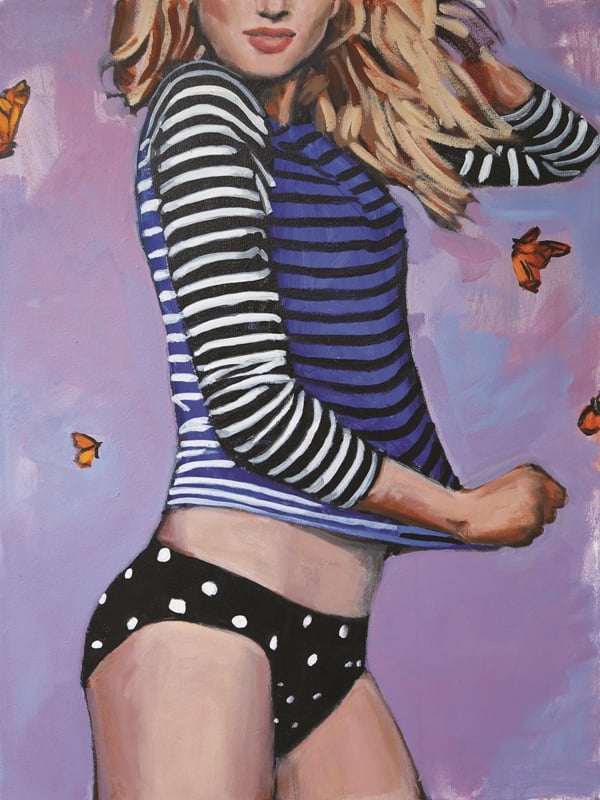

Walter Robinson, Sun, Surf, and Style: the Swim Tee, Ride the Wave (2014). Image: Courtesy of the artist and University Galleries, Illinois State University.

The show, which is Robinson’s first solo museum retrospective, was first staged at the University State Galleries of Illinois State University, Normal, where Blinderman is curator.

In contrast to Blinderman’s enthusiasm, Robinson deflected our attempt to congratulate him on the show in his typical self-effacing style. “Luckily, I still had most of the paintings in my possession,” he said, “so it wasn’t that hard to organize.”

Related: David Ebony Interviews Artist and Editor Walter Robinson on His Parallel Lives

Many know Robinson primarily as a writer and editor. After writing for Art in America for two decades, he founded artnet magazine, the predecessor to artnet News, in 1996, before many people were using email. He continued there until the magazine’s closing in 2012, at which time he returned to painting. Since then, his artwork has come back into the public eye, with shows including a 2014 solo at New York’s Lynch Tham Gallery.

Walter Robinson, Amboy Dukes (1981).

Image: Courtesy of the artist and University Galleries, Illinois State University.

The 80 paintings in the retrospective span from 1979 to the present, and encompass many of the artist’s themes, including, in addition to the subjects noted above, still lifes of pharmaceutical products and alcoholic beverages, portraits of family members and fellow artists, spin paintings (predating those of a certain YBA), and pornographic imagery.

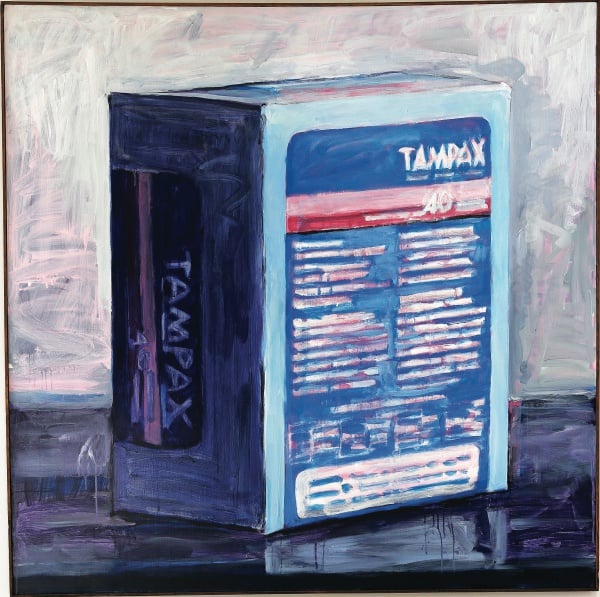

An early canvas, Woman III (1984), with its unmistakable allusion to Willem de Kooning, partakes not only of high-minded references but also of crass humor—its subject is a Tampax box. The brushy treatment of the background hazily refers to the legacy of the Abstract Expressionists that still hung heavy over Robinson’s adopted city, where he had come from Tulsa, Oklahoma, to study art history and psychology at Columbia University.

A more recent painting, Savarin (2013), shows a container of McDonald’s French fries. Even this depiction of a guilty pleasure holds a sly allusion, here to Jasper Johns’s sculpture of a Savarin coffee can filled with paintbrushes. In Robinson’s take, the artist’s tool has morphed into a high-calorie, salty indulgence.

Walter Robinson, Woman III (1984).

Image: Courtesy of the artist

“Ah, yes,” Robinson joked, speaking of that painting, “it’s the threshold between the spiritual and the carnal.”

Robinson’s joking fails to mask his seriousness; the writer Carlo McCormick has said that his work displays “a devious sense of irony done with incredible sincerity.” In 1983, as deconstructionist philosophers argued that everything was a social construct and nothing genuine, he undertook to paint his wife and his young daughter, on the premise that his love for them was anything but constructed.

Even so, his depictions of them are somewhat cheeky. One painting shows his wife at her toilet, but with a twist. “It’s the first painting of a woman flossing in the history of art,” Blinderman said. “I guarantee it.”

Intimacy and art are tricky territory, as we see in two recent paintings based on pulp fiction book covers. My Love is Violent (2011) has a moody-looking artist leering at his model, who’s just pulled on a robe, as he shows her his canvas. The painter in Art Colony (2012) seems less menacing, with his blond hair, smile, and pink pants, but his busty model seems apprehensive as he grasps her by the shoulders.

Walter Robinson, Untitled (Red Kitty) (1982).

Image: Courtesy of the artist

Elsewhere, Robinson’s enterprise is seemingly more dryly intellectual, as in his paintings of clothing and models from Land’s End and J. Crew catalogues. Even there, though, his subject is lust of a consumerist sort.

Standing in front of Lavender Shadow Plaid (2014), depicting the image of a button-down shirt from a catalogue, Blinderman pointed out that it’s perhaps no accident that the image of a garment served Robinson as a readymade, since Duchamp appropriated the word readymade from the textile industry when mass-produced clothing was new. Before that, he pointed out, we all went to tailors.

“And,” he went on, “the shirt is wrapped around a cardboard support just as a canvas is wrapped around a wooden frame, so I don’t think this painting is just a comment on geometric abstraction.” Pointing to a nearby painting of a pair of boots, he said, “and I don’t think that one is just a comment about Vincent van Gogh’s painting of shoes.”

“Did Walter have all this in mind?” he said. “I don’t know, but it’s all part of the game.”

“Walter Robinson: Paintings and Other Indulgences” is on view at the Galleries at Moore College of Art & Design through March 12, 2016.