For decades, Massachusetts’s Worcester Art Museum has displayed the portraits of early American men and women, painted by artists such as John Singleton Copley and Gilbert Stuart. Often commissioned by the subjects themselves, the portraits burnished the sitters’ appearance and reputation. Now, in an effort to cast these figures in a more historically accurate light, museum curators are adding revealing new layer to the works: wall labels that clearly identify subjects with ties to slavery.

“These paintings depict the sitters as they wish to be seen—their best selves—rather than simply recording appearance,” reads a new introductory label in the early American galleries at WAM. “Yet a great deal of information is effaced in these works, including the sitters’ reliance on chattel slavery, often referred to as America’s ‘peculiar institution.’ Many of the people represented here derived wealth and social status from this system of violence and oppression, which was legal in Massachusetts until 1783 and in regions of the United States until 1865.”

The museum aims to point out an ugly truth: The wealthy patrons that commissioned so much of our nation’s early art often financially benefitted from the institution of slavery. Many were slaveowners themselves. This information, previously glossed over, provides new insight into the works: The evils of slavery provided, in part, the means that allowed the portrait sitter to hire an artist to capture their likeness—it’s no coincidence that there are no portraits of African Americans from this period at the museum.

Joseph Badger, Rebecca Orne (1757). New signage at the Worcester Art Museum reveals that Orne’s father, Timothy Orne, owned a fleet of over 50 merchant ships that sometimes transported slaves. Courtesy of the Worcester Art Museum.

“Labels are a significant way museum goers engage and interact with an object. In the old label, the focus is on the artist’s technical skill or the sitter’s biography. But the new label encourages us to think about what is not visible in the painting and alters how we view the portrait,” Erin R. Corrales-Diaz, the museum’s assistant curator of American art, told artnet News in an email. “How might our understanding of the paintings change when these statements of fact are presented straightforward manner?”

The wall label project was the brainchild of Elizabeth Athens, the museum’s former curator of American art, who was activated by the 2016 election to revisit the less-positive biographical details of the people depicted in the museum’s American portrait collection. (Athens is now a postdoctoral research associate at the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts, at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC.)

In drawing out this information, Athens told Hyperallergic that she wanted to acknowledge “the complete erasure of people of color, both in the objects displayed and the way the objects were addressed.”

“We tend to think of New England and Massachusetts in particular as an abolitionist state, which it was, of course, but there’s this kind of flattening of the discussion of slavery and its history in the states—that the North was not at all complicit and it was a Southern enterprise,” Athens told WBUR.

The Worcester museum’s new policy shatters that illusion, outing portrait sitters from New England for their ties to slavery. The wall text also allows the museum to paint a fuller picture of the early American economy’s dependence on human bondage, even in the North.

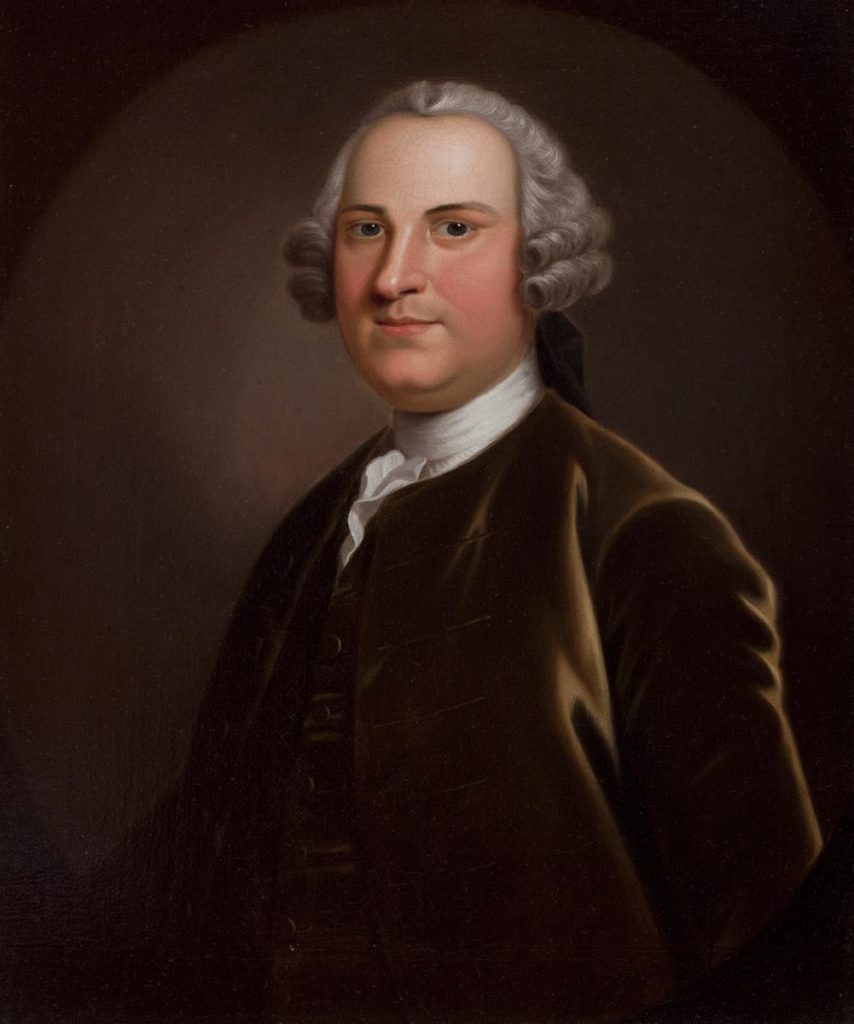

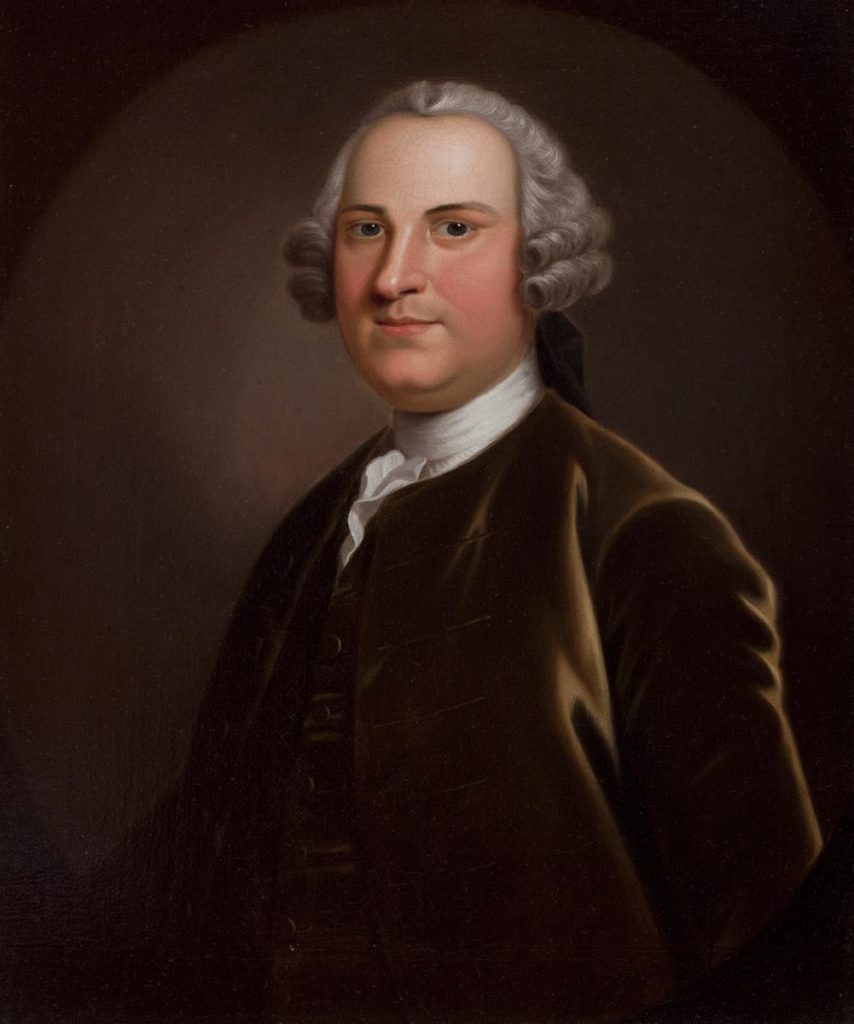

John Wollaston the younger, Charles Willing (1746). New signage at the Worcester Art Museum reveals that Willing owned a “Negroe Wench Cloe,” a “Negroe Girl Venus,” a “Negro Man John, and a “Negro Boy Litchfield.” Courtesy of the Worcester Art Museum.

“It is extremely important to underline how the institution of slavery was a national and global phenomenon,” added Corrales-Diaz. “One did not have to own an enslaved person to participate and benefit from slavery.”

Charles Willing, a Philadelphia merchant painted by John Wollaston in 1746, for instance, owned a “Negroe Wench Cloe,” a “Negroe Girl Venus,” a “Negro Man John, and a “Negro Boy Litchfield,” according to historical documents cited in new wall text. A 1757 painting by Joseph Badger of a young girl named Rebecca Orne is also implicated, by her merchant father’s fleet of vessels, which counted slaves, as well as fish, grains, molasses, and rum, among their cargo.

“The label writing actually didn’t take long, thanks to the comprehensive research by David Brigham on WAM’s Early American Paintings timeline,” Athens told artnet News in an email. “Much of the information was already in the files or on the website; it just wasn’t called out.”

This kind of consideration given to wall labels is becoming more and more necessary for museums. Curators have increasingly included background information about controversial contemporary subjects. Floyd Mayweather Jr.’s portrait, for example, was displayed in 2014 at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery with a label noting that he had been “charged with domestic violence on several occasions.”

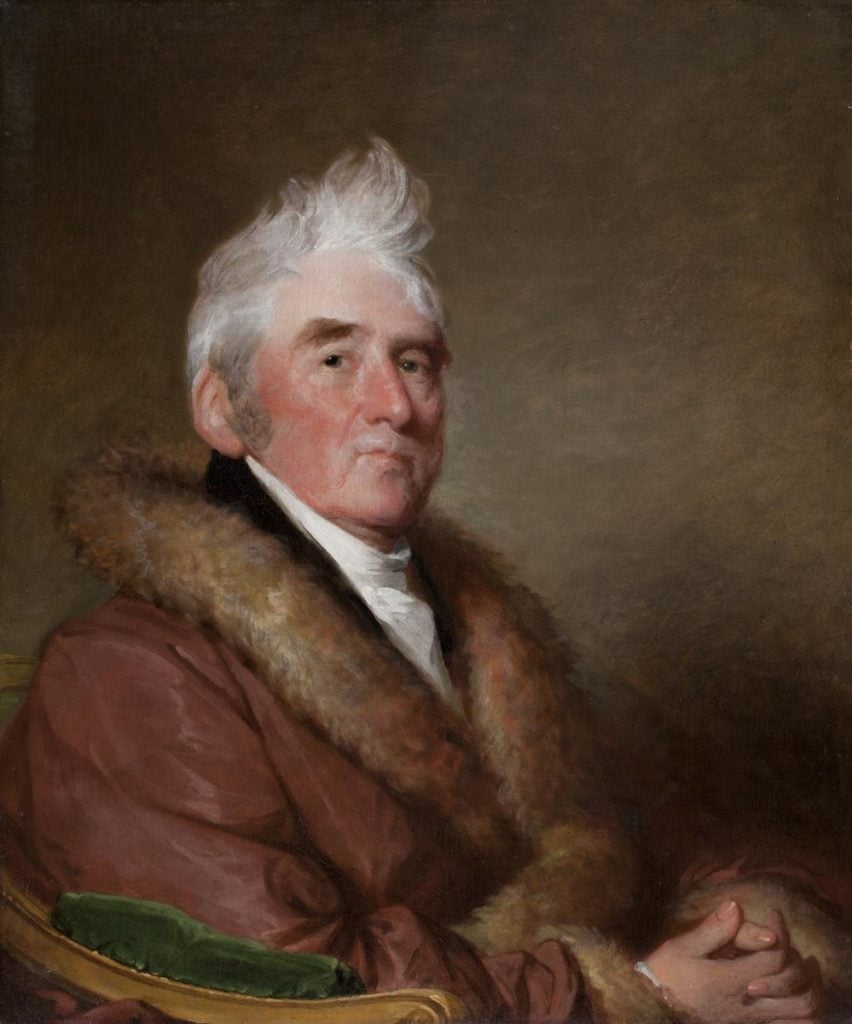

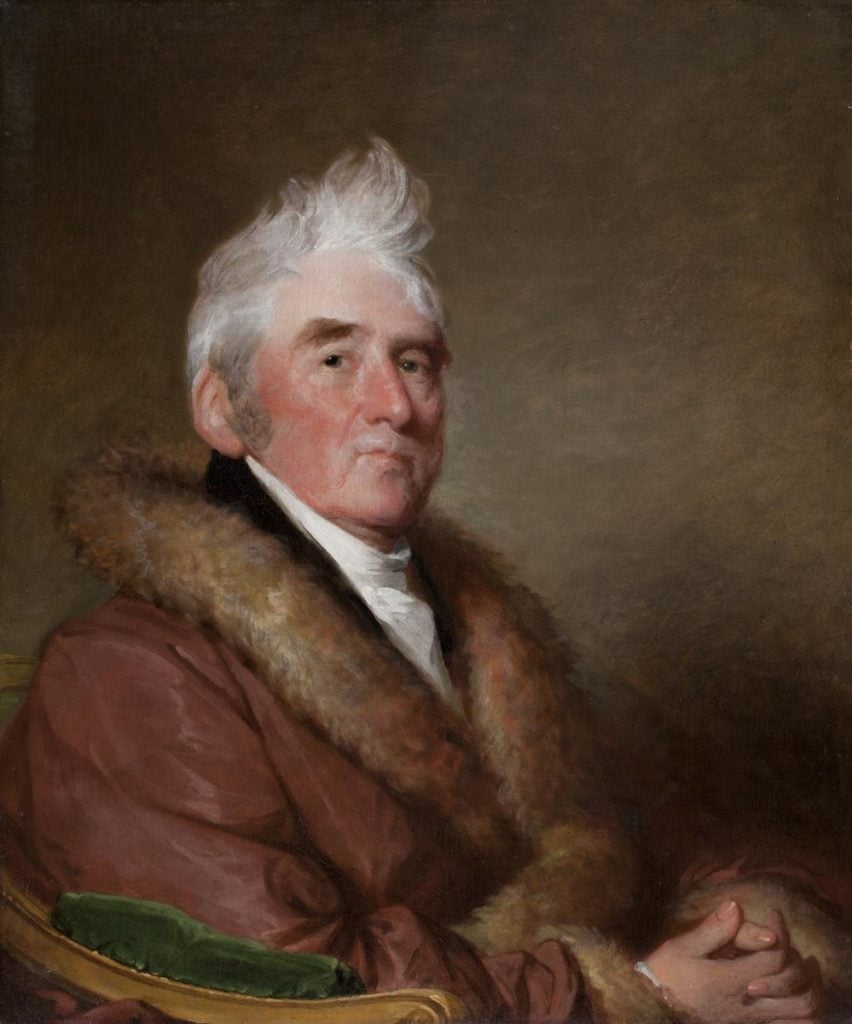

Gilbert Stuart, Russell Sturgis (1822). New signage at the Worcester Art Museum reveals that Sturgis’s relatives conducted business in what is now Haiti and were involved in the slave trade. Courtesy of the Worcester Art Museum.

Now, in the wake of the #MeToo movement, institutions are also taking a closer look at the artists and their behavior. The National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, postponed upcoming exhibitions of Chuck Close and Thomas Roma after two men were accused of sexually inappropriate behavior.

There have even been calls to put asterisks next to paintings by Pablo Picasso, accused in biographies of behaving violently toward women, and Egon Schiele, charged but later acquitted of kidnapping and statutory rape of a 13-year-old girl.

With its new approach to historical portraits, the Worcester Art Museum is taking things one step further. Not only is the institution refusing to allow white figures off the hook for their ties to slavery, it is showing how these subjects’ status and wealth were directly informed by the inhumane institution.