The 1980s are back—and not just in the latest season of the Netflix series Stranger Things. The work of late artist Steven Parrino—who became famous for his signature torn, crumpled and twisted canvases and sculptures that were once synonymous with bad-boy art of the ’80s—has been cropping up everywhere in recent months.

Gagosian—which has represented the artist’s estate since 2006, the year after the artist’s untimely death in a New Year’s Eve motorcycle accident at age 46—has been doing the heavy lifting. Last month, the gallery presented Parrino’s 13 Shattered Panels (for Joey Ramone), a large-format, site-specific installation of folded, crumbled, and torn painted plasterboard, in Art Basel’s Unlimited sector for monumental art. And at the most recent Frieze Art Fair in New York, the gallery juxtaposed Parrino’s work with pieces by chrome sculptor John Chamberlain to illustrate how both explored the act of folding and compressing materials.

The first solo show of Parrino’s work in New York since 2007 is also currently on view at Skarstedt in New York (through July 15). In London, meanwhile, Skarstedt is showing “Push/Pull” (through August 2), which presents Parrino’s work alongside art-market heavyweights such as Lucio Fontana, Cady Noland, Richard Prince, Richard Serra, and Christopher Wool.

Steven Parrino, Purple monster shifter (in 3 parts) (Executed in 1994). Image courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Retro or Revolutionary?

Whether Parrino’s work is considered tired or timeless depends a bit on who you ask. Jerry Saltz, a Parrino skeptic but eventual convert, initially dismissed it as a “mannered, Romantic, formulaic, conceptualist-formalist heavy-metal boy-art abstraction”—a predecessor to the gobbled up-and-then-spit-out Zombie Formalism of the mid-2010s.

To Parrino’s supporters, his work is an intoxicating mix of nihilism and wholehearted commitment to painting. It offers a link between destructive creators like Lucio Fontana, Lee Bontecou, and John Chamberlain and contemporary bad boys like Banks Violette and Nate Lowman. Parrino’s detractors dismiss him—and those influenced by him—as macho art born in a moment of excess that may not stand the test of time.

The artist, who was rarely seen without a leather jacket, had said he came of age when “the word on painting was ‘Painting Is Dead,’” but “saw this as an interesting place for painting… and this death painting thing led to a sex and death painting thing… that became an existence thing.” He described his slashed, mutilated, scorched, and twisted canvases as “misshaped paintings”: a retort to the shaped paintings of the ’60s.

Steven Parrino, Jerk Left Jerk Right (1989). Image coutesy of Phillips.

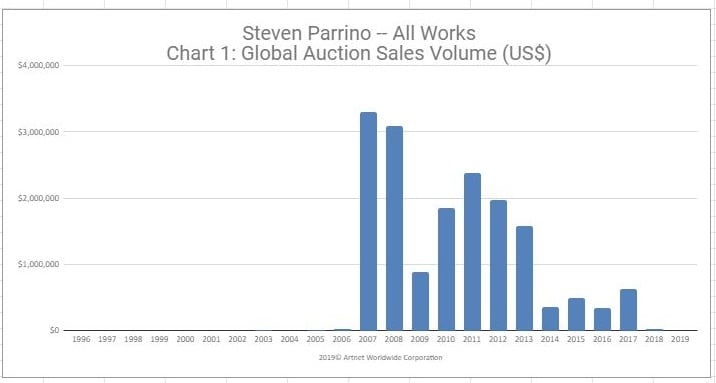

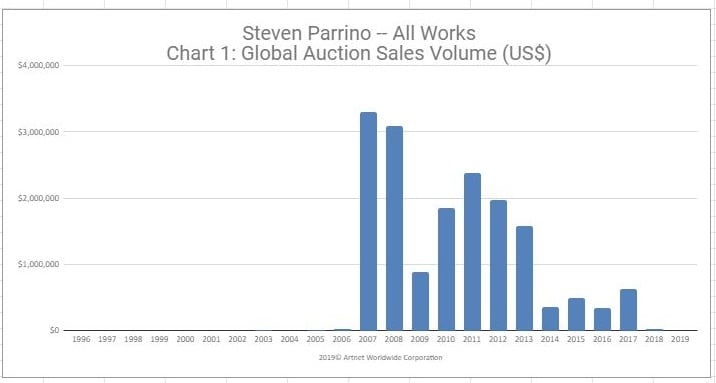

Although Parrino has been consistently well collected, his market really began to take off in 2007, two years after his death, when the Palais de Tokyo in Paris staged a major survey of his work and Gagosian mounted an ambitious exhibition after taking over representation from the artist’s longtime dealers, Team Gallery in New York and Massimo de Carlo in Europe.

José Freire of Team told New York Magazine at the time that “in eight years and five solo shows I sold two paintings; one for $9,000, the other for $10,000.” In 2007, Parrino’s major paintings were reportedly on offer at Gagosian for 100 times that figure, north of $1 million. (Since then, Gagosian has shown his works in 18 exhibitions in eight countries and placed them in collections including the Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York.)

Today, on the private market, Parrino paintings reportedly sell for as much as $1.5 million. His auction record is lower: $965,863 (£601,250) for Purple Monster Shifter (1994), a three-part work sold at Sotheby’s London in June 2011. His top 10 auction prices are all between $500,000 and $1 million for works largely dating from the late ’80s to early ’90s. In all, the artnet Price Database lists 113 auction results for Parrino. Of these, 26, or 23 percent, went unsold.

Courtesy of the artnet Price Database.

An Auspicious Moment

On both the primary and secondary markets, Parrino’s monochromatic, draped canvases are the most coveted, as well as those accompanied by Pictures Generation-esque words (“Idiot/Idol; “Jerk”). “Despite when they were made, I think the works look so classical now especially when placed in context with Richard Prince and Cady Noland,” Per Skarstedt, who says he has been gathering Parrino works since 2008, told artnet News in an email.

In 2007 and 2008, around the time of that first major Gagosian show, there was also a surge of sales at auction—and a surge in speculation—prior to a sharp drop in 2009. Since that time, and other than a brief lull coinciding with the 2009 financial downturn, “we’ve seen less and less very major works coming to auction,” Max Moore, head of the afternoon session of Sotheby’s contemporary art day sales in New York, tells artnet News.

Auction-house executives say the major limiting factor in the artist’s market now is supply. John McCord, a contemporary specialist and head of the morning sale at Phillips, notes that Parrino “was prolific in his time, but he died so young and left behind a relatively small body of work, so there’s a scarcity.” He credits Massimo Di Carlo, who showed Parrino’s work early on, with placing it particularly carefully with collectors—primarily Americans and Europeans—who have held onto it.

That may begin to change, however, with all the buzz around the Skarstedt shows. “With the right piece at the right estimate, we’re going to be breaking the artist record very shortly with the demand that we’re seeing now,” Moore says. Skarstedt confirmed to artnet News that most of the works have already been sold to European private collectors and museums at prices ranging from $800,000 to $1.5 million, the latter of which is well above the current auction record.

And with the rising interest and demand, it seems even loyal collectors are increasingly tempted to sell. A Gagosian representative credited the current buzz to the 2017 exhibition Dancing on Graves at the Power Station in Dallas, as well as renewed interest in artworks from the 1980s more broadly. “This has resulted in several successful sales at auction and private transactions,” she said.

Steven Parrino, For Pierre Huber (1990). © Steven Parrino. Image courtesy of Skarstedt, New York.

Moore also sees opportunity for newer collectors in Parrino’s works on paper, which have a far lower price point ranging from $50,000 to $75,000 privately. (At auction, those estimates would likely be more conservative, starting around $30,000.) The works on paper and photo-collages “capture the same kind of turbulent, stressful process with which” he created canvases, Moore says.

“I think you’re going to see a shift now,” Moore concludes. The Skarskedt exhibitions “have the potential of showcasing Parrino to a new body of collectors to engage in the market for the first time, or maybe for the second time to add a new piece to the collection.” They also, he adds, illustrate “how he [Parrino] can play with the big boys—and always has been able to.”