Market

Will the African Art Market’s Recent Rise Withstand the Shutdown? Dealers Say There’s Reason for Hope

Dealers say that the market is buoyed by accessible price points.

Dealers say that the market is buoyed by accessible price points.

Naomi Rea

The market for contemporary art from Africa has grown steadily over the past five years, but as the pandemic wreaks havoc on economies around the world, volatile local markets could leave many parts of the continent vulnerable to the ongoing instability.

Dealers based in Africa were among those who expressed the most optimism about 2020, according to economist Clare McAndrews’s annual art market report, released at the beginning of the year. An increase in global visibility—in part due to platforms such as the contemporary African art fair 1-54 and a speculative secondary-market interest in African artists—were among the reasons that 90 percent of those interviewed predicted that sales would continue to grow over the next five years.

But while early indicators suggest that interest in contemporary African art has persisted, it remains unclear if there will be the market infrastructure necessary to support it.

Touria El Glaoui. Photo by Victoria Birkinshaw.

The 2020 edition of the 1-54 fair in New York was put off for a year and replaced by a virtual edition in May. Organizers say they exceeded expectations under the circumstances, with 70 percent of galleries selling between one and three works priced between $3,000 and $12,000—a relatively low range that may have been better poised to attract buyers in the down market.

“The general attitude towards art right now is a slowdown globally, and I can imagine that we will be impacted as well,” Touria El Glaoui, the founder and director of 1-54, tells Artnet News. “But at the same time, because the access price point is much lower than most of the other regions, we are in a better position to be more accessible online than a lot of the artworks that are priced much higher.”

Aissa Dione, the founder of Galerie Atiss in Dakar, Senegal, tells Artnet News that she was “encouraged” by her participation in the online fair. “The local art market struggles at the best of times,” Dione says, adding that the cancelation of international art fairs as well as the Dakar Biennial which often draws international collectors made the situation more acute. For her, the moment has “re-emphasised the need for a sophisticated online strategy, as an alternative means of projecting the gallery and reaching markets beyond its geographical location.”

It is still uncertain whether the Africa-based edition of the fair, 1-54 Marrakesh, will go ahead next year. El Glaoui was planning to move the fair’s dates to March in order to avoid a clash with Cape Town Art Fair in February, but given Morocco’s strict lockdown regulations, it is too early to say when normal activities, and international travel, will resume.

Meanwhile, art fairs in South Africa and Nigeria, which mostly cater to their respective local markets, are forging ahead with in-person events so long as public health regulations allow it.

Installation view “Paraboles d’un règne sauvage” by Serigne Ibrahima Dieye. Image courtesy Galerie Cécile Fakhoury.

The Ivory Coast-based gallerist Cécile Fakhoury, who has spaces in Dakar and Abidjan and a showroom in Paris, says that her focus will also be on growing the local markets. The gallery has continued to make sales online through its website, but it continues to be an uphill battle to convince collectors in the West to wire money to Africa.

“In the minds of a lot of people, it is still not safe to send money to Africa,” Fakhoury says, adding that she is working on developing solutions to reassure collectors.

While the lack of access to the international market has limited the gallery’s reach, it has also reduced the costs usually associated with participating in external events and art fairs. As a result of this, and because the gallery’s exhibition of the artist Serigne Ibrahima Dieye sold well before lockdown (prices ranged from €4,500 to €15,000), Fakhoury says the deficit has “balanced out” at her gallery.

“I have this feeling that the crisis will bring more focus and more effort and energy to the local market,” Fakhoury says. “In a way, if we are doing less outside, we have more time, and more money, to do more inside.”

Harsher strain can be felt when it comes to emerging galleries, particularly those located in countries with more fragile economies. Janire Bilbao, the founder of MOVART gallery in Luanda, Angola, tells Artnet News that the pandemic has catapulted the country into social chaos. The economy has been suffering since the 2014 oil crisis, and this year’s plummeting prices has had a dire effect on the country, where oil accounts for 90 percent of its exports.

While MOVART has been able to reopen after two months of lockdown, Bilbao says that she has not seen collectors return to the gallery. “We fear local collectors will be more impacted than our international clients as the crisis deepens in Angola.”

Still, Bilbao is optimistic about the future of selling art online, setting her hopes on technologies that allow remote clients to picture artwork in their homes. “We of course also will continue to organize exhibitions and participate in art fairs when possible, but this pause has been an accelerator for new technologies and remote investment that applies also to the art world,” she says.

Daudi Karungi, the director of Afriart Gallery in Kampala, Uganda, shares concerns about the local economic impact of the pandemic. While his gallery continued to sell work throughout lockdown—mostly to international collectors buying at a price range of $2,000 to $20,000—he isn’t sure whether the local market will respond similarly. “We might see less addition of new domestic collectors because of the new priorities on how they will spend their money,” Karungi says.

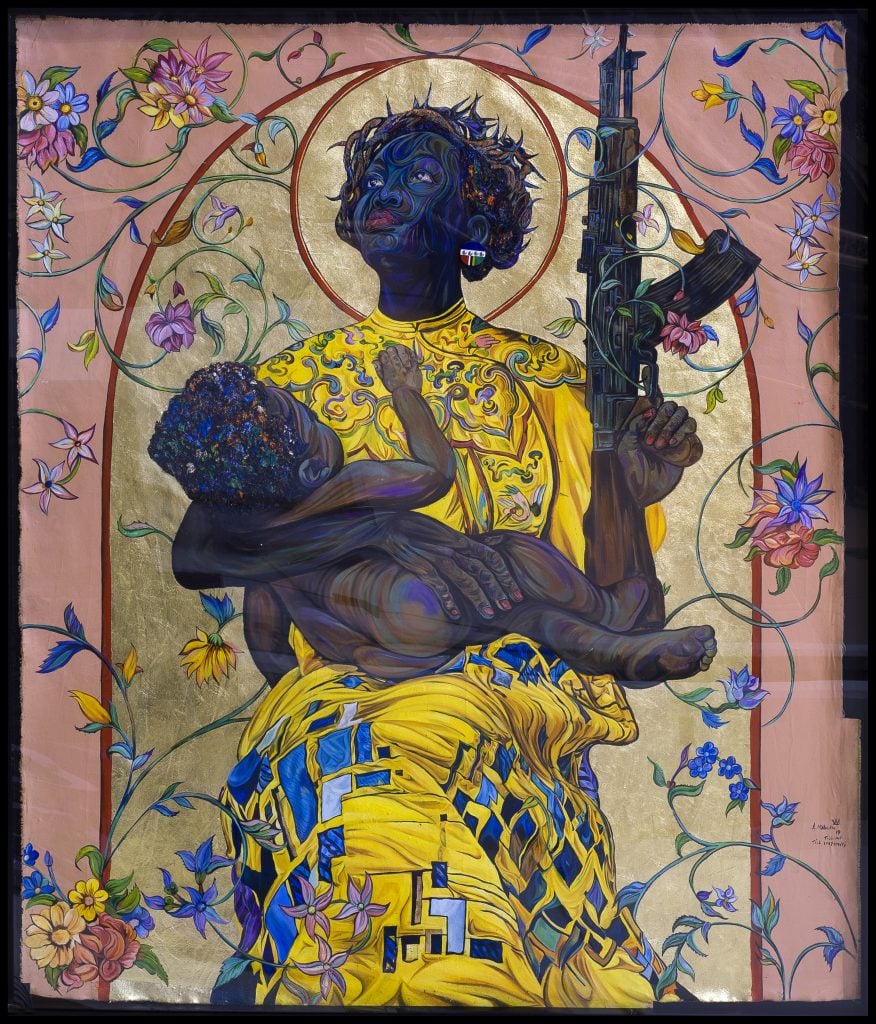

Ayanda Mabulu, Till Infinity (2019). Courtesy Kalashnikovv Gallery.

MJ Turpin, one of the cofounders of Kalashnikovv gallery, based in Johannesburg and Berlin, says that despite South Africa being hit hard by the virus, collectors have responded positively to the gallery’s online focus. “It has shown healthy growth and, not surprisingly, is supported in the majority by younger collectors and corporate professionals from both abroad and locally,” Turpin says.

“I think the African market will be far more resilient, if not robust, in returning immediately to an upward trajectory,” Turpin says, adding that he also expects “increasing focus and attention from internationals based on more ‘bang for their buck’ mentality and buying strategies.”

Installation view of Julio Rizhi, “Chakafukidza,” at First Floor Gallery Harare. Image courtesy the gallery.

Valerie Kabov, the director of First Floor Gallery in Harare, Zimbabwe, tells Artnet News that she hopes the accessible price points of African art will continue to draw collectors. “African art is still an under-explored and growing segment of the market in which remarkable returns can be achieved,” she says.

Kabov also puts her faith in the region’s long-running resilience in the face of adversity. “Galleries in most African countries operate in conditions that require flexibility and adaptability to unpredictable conditions and crises,” she says.

Plus, the ongoing global reckoning with the Black Lives Matter movement could also translate into more spaces being created for under-represented artists, she says, which would set a course for success long beyond the immediate concerns of the pandemic.