Welcome to New Models, a series that highlights galleries innovating beyond the traditional ways of exhibiting and selling art in the primary market. From forward-thinking collaborative initiatives to novel uses of technology, the concepts it unpacks prove that there are more paths to success and sustainability as an art dealer than the default settings.

The mythology and allure of the art dealer tends to revolve around one of the same idealized traits as the mythology and allure of the artist: rugged individualism.

Of course, everyone knows that this setup is almost always an exaggeration. Very few galleries survive, let alone thrive, without a group of smart, hardworking, and well-connected people all hustling together in lockstep. Yet this more complicated reality largely plays out behind the scenes. And in most cases, collectors and viewers still experience the results by walking through a door with just one dealer’s name above it. This tends to be true even if the operation grows to include multiple partners—a title that, depending on the gallery, could mean anything from strictly hierarchical seniority, to a share of profits, to an actual ownership stake in the business.

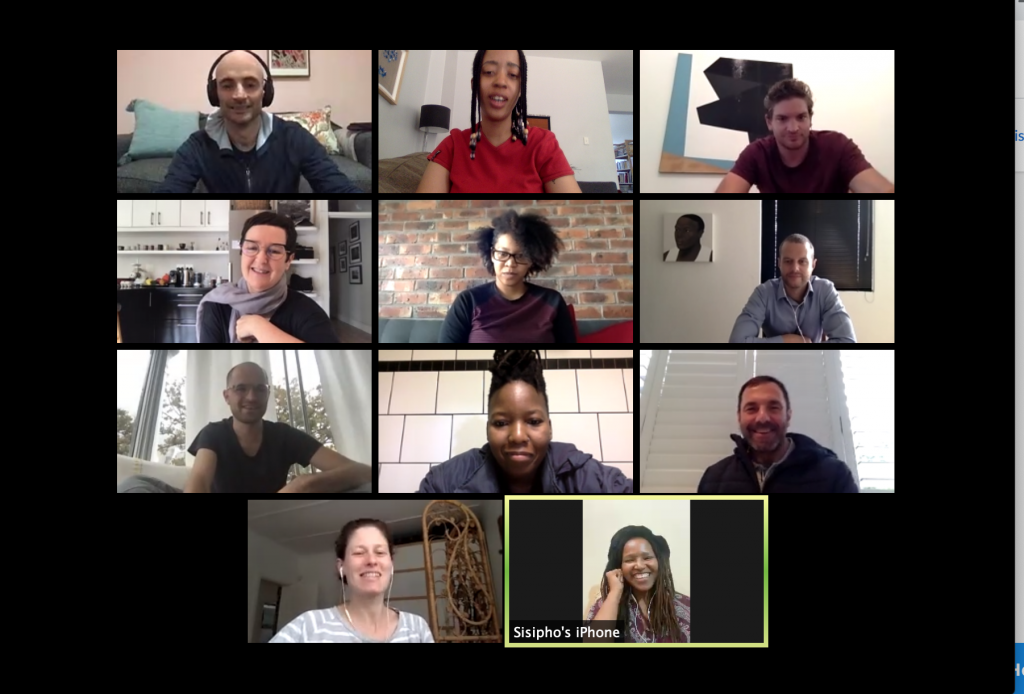

The South African gallery Stevenson has flourished through a partnership model that, if not unique, remains decidedly rare in the private market. Founded in Cape Town by Michael Stevenson in 2003, the business now exists nearly two decades later under a model most often associated with law firms and advertising agencies. The gallery is jointly held by 13 partners (including Stevenson himself), each with an equity stake no larger than 12.5 percent and a level of decision-making authority that their counterparts at other galleries don’t always enjoy.

While there’s certainly more to the story than an atypical organizational structure, that structure has been crucial to the gallery’s development. Here, in July 2020, Stevenson features an internationally respected program that is regularly visible at fairs such as Art Basel and Frieze London, as well as permanent locations in Johannesburg and Cape Town, an office in Amsterdam, and roughly 25 staff members (excluding the 13 partners). And the gallery’s journey to this point includes rich food for thought about alternative ways to sustain and succeed in a historically difficult market that has only grown more tumultuous of late.

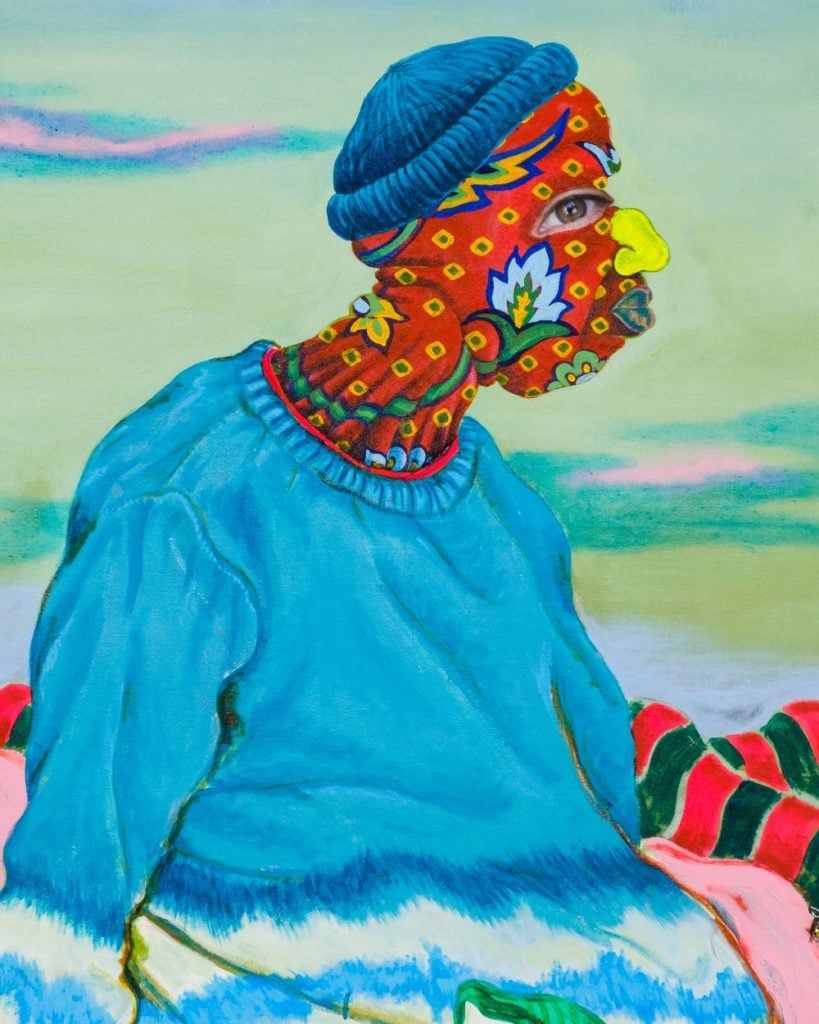

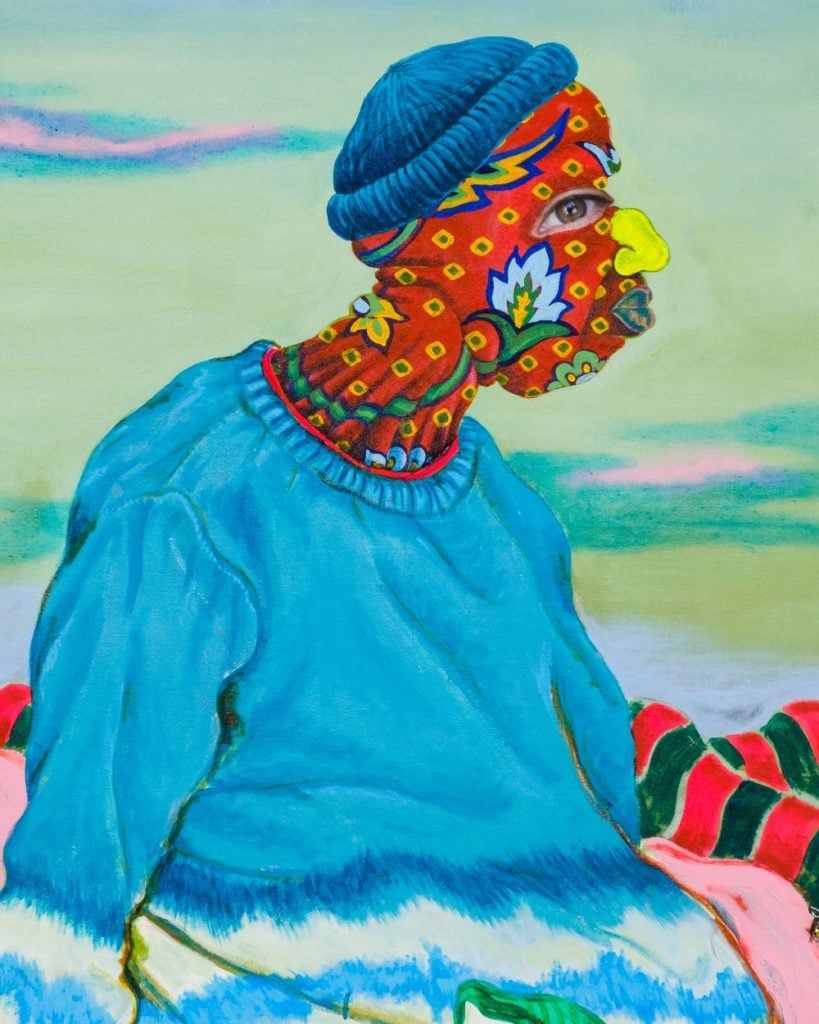

Simphiwe Ndzube’s Mazembe (2019) © Simphiwe Ndzube. Courtesy of Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg.

Step by Step

Like the physical gallery, the business model has expanded gradually. In 2011, Michael Stevenson sold the company’s first equity shares to his five gallery directors, all of whom are still partners today. Additional partners joined the ownership structure in pairs and trios over the coming years, with the final two stakes being claimed in early 2020. The gallery’s equity is now fully distributed, meaning any future partners could only join if one or more of the current partners exited or diluted the size of their share.

According to Joost Bosland, one of the five original Stevenson partners minted in 2011, shared ownership imbues several advantages absent from more traditionally structured galleries. He describes the cumulative effect as making the gallery more “antifragile,” a term for enhanced sustainability in a chaotic world coined by best-selling author and risk analyst Nassim Nicholas Taleb in a 2012 book of that name. (Bosland clarified that Taleb’s ideas did not motivate the formation of the Stevenson business model, but that they remain useful as a framework to think through it.)

Specifically, distributing ownership widely and strategically produces four core benefits.

1. Better Talent Retention

Stevenson’s expanded ownership pool has given its high-achieving staff members greater incentive to stay on long term—an incentive Bosland spoke to from personal experience. “I would have probably been here either way,” he says, “but it’s been a lot easier to not even consider other job offers because I’m literally and figuratively invested in the business.”

But the draw comes from much more than just increased professional authority and standing. A gallery with 13 stake-holding partners is also a gallery where the demands of partnership are distributed much more broadly. The result, according to Bosland, is that Stevenson’s leadership enjoys significantly better work-life balance than solo gallery owners. Case in point: When he spoke to Artnet News in early March (before the enormity of the present global health crisis had emerged), Bosland had just returned from 10 days away from the gallery with no internet access—a prospect as unachievable by the average dealer as snatching a live bird out of the sky with their bare hand. But he emphasizes that the benefits of the large-partnership model are just as significant for the day-to-day operational necessities of the gallery as the rare planned vacation.

“Sharing the stress of having to pay salaries every month makes a real difference. It feels like we’re in it together,” he explains.

2. Wider Engagement by Ownership

As the saying goes, there’s strength in numbers. Stevenson’s business structure enables gallery stakeholders to attend to the maximum number of obligations and events produced by the nonstop global art industry. Even in the digitally-centered, travel-restricted “new normal” of summer 2020, it remains impossible for a single gallery owner to reach every valuable touchpoint on the calendar. True, galas and art fairs may be relics of a bygone age for now. But online art fairs and virtual events are proliferating, collectors are still willing to buy if properly engaged, artists are still seeking guidance on new works, and much more. A gallery with 13 true decision-makers still may not be able to cover everything, but it can do exponentially more than a gallery effectively controlled by a single owner.

Bosland posits that more traditionally structured galleries cannot fully compensate just by increasing staff size, either. In key situations, there is “a very real desire on the part of collectors and artists to speak to someone who has final authority” about the matter at hand. No matter how competent and charming a director or a partner in name may be, they can only provide so much value if they still need a higher-up’s approval before acting. This means Stevenson’s business model doesn’t just widen the gallery’s reach; it also amplifies the gallery’s efficiency.

Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi, Team (2020). Courtesy of the artist and Stevenson, Johannesburg.

3. Greater Diversity

At Stevenson, this advantage accrues on two different levels: professional specialization and demographic perspective.

Within its leadership tier, the gallery exemplifies what economists would call emergent order: a system that organizes itself organically through individual choice rather than by top-down fiat. The degree of specialization varies between partners, according to Bosland, but the point is that each one has inherent strengths and a “natural, deeply felt voice” that lends itself to certain areas of expertise.

For instance, he describes one partner as the “in-house artist voice” who can be counted on to think through every decision from the vantage point of Stevenson’s roster members. Another partner has always gravitated toward the secondary market, ensuring resale strategy will stay front of mind. This is not to say that other partners ignore particular questions, only that each one is freer to concentrate on what they do best than the average dealer who must make the final call about everything, regardless of their comfort level.

Just as important, Stevenson’s distributed ownership structure has resulted in an atypically broad set of identity groups having a true seat at the table. Of the gallery’s 13 current partners, a majority (seven) are women, and four identify as Black or of color. Overall, the group ranges from roughly age 26 to age 56. And while Bosland emphasizes that a diverse leadership group would be an asset for a gallery based anywhere in the world in 2020, it is essential in a country with as complex a history as South Africa.

“Especially in the current climate, debates about these things are so alive,” says Bosland. “Having someone who is a fellow owner in the business speak about a certain issue from a particular point of view is incredibly valuable.”

Pieter Hugo, Abdullahi Mohammed with Gumu, Ogere-Remo, Nigeria,

2007. Courtesy Stevenson, Cape Town.

Two Sacrifices

Just as Stevenson’s unorthodox business model brings advantages most other galleries don’t enjoy, it also brings challenges most other galleries don’t have to face.

The first and most obvious of these is a dramatically reduced profit split for the partners. Few galleries at or below Stevenson’s level in the commercial hierarchy sell enough for a sole owner to live particularly comfortably even in banner years. Divide the profit with 12 other partners, and each individual’s annual compensation plummets like a boat anchor chucked into calm seas. In this sense, every one of the gallery’s many partners could be considered underpaid relative to their counterparts at similarly sized galleries.

At the same time, shared ownership also means shared risk—which translates into dramatically reduced losses in leaner years, as well as the higher quality of life from the distributed responsibilities mentioned earlier. Bosland defines the overall trade-off as one that Stevenson’s partners are “more than happy to make.”

Yet shared responsibility also leads us to the other major challenge of having so many partners: How do you make organizational decisions among 13 stakeholders?

Bosland acknowledges that the process had its “growing pains” during the transition from sole ownership to collective ownership—and those growing pains were felt as much by clients as by the partners and staff themselves. “Certain collectors and artists were a little confused about who they should be speaking to, how decisions were made, who they should address certain questions to,” he recounts. “So we had to work on that.”

Nor was this simply a one-off riddle to solve when the first five partners joined Michael Stevenson in the ownership structure in 2011. In fact, the challenge has been even more layered because, according to Bosland, the partners have never made organizational decisions by simply voting. Instead, they’ve developed what he describes as a “consensus-based” structure: no dramatic moves are made until everyone agrees.

Maintaining this approach meant that the dynamics had to evolve every time the leadership pool incrementally expanded between 2011 and today. Reaching a consensus among 13 valued colleagues is as different from doing so among nine as reaching a consensus among nine valued colleagues is from doing so among six. This is especially true given that Stevenson’s ownership base is not perfectly horizontal; again, different partners hold shares of different sizes, and have held them for different lengths of time. In short, it’s complicated.

“I partly grew up in a commune, so it reminds me of that at times,” says Bosland. “It can be quite a beautiful process—but not always.”

He notes that the quasi-utopian dimension of Stevenson’s model has had a tendency to attract skepticism. Yet the partners have now been successfully navigating the rapids for nine years and counting. If that record doesn’t qualify as proof of concept, it’s hard to imagine what would.

Berni Searle Still (2001). Copyright Berni Searle. Courtesy Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg.

What’s Next?

The best answer to the proof-of-concept question may lie in how the gallery weathers the unique storm that is 2020. South Africa’s economy was largely placed on lockdown from mid-March through June due to public-health risks. Although Stevenson’s spaces in Cape Town and Johannesburg are both back to full operating hours and full salary for staff at publication time (with employees working from home as manageable), the global art market will take a kind of ever-shifting mutant shape for the foreseeable future. Stevenson, like all dealers, will have to adapt in response.

That process is underway. The gallery expanded its digital presence by joining the online-art marketplace Ocula early in the shutdown. A more recent strategic consideration among Bosland and his 12 fellow partners is how the gallery can best leverage its Amsterdam office in an industry poised to be without either art fairs (or easy international mobility, period) until some unknown point ahead. When fairs do return, he also imagines Stevenson will exhibit at fewer of them than in years past. But like seemingly everything else this year, the situation is fluid.

No matter what happens next, though, Bosland is optimistic in no small part because of Stevenson’s unorthodox ownership structure—and more importantly, who it comprises.

“Our model means that 12 of the brightest people I have ever worked with share a vested interest in pulling the gallery through this moment, and all of us are going above and beyond in ways that would be hard to expect from even the most loyal employees,” he explained. “But more than that, it means every step we take has been considered from many angles, and we share the burden of making tough decisions.”

“At times we might feel overwhelmed, but we never feel alone.”