Analysis

The Gray Market: How Art Basel Could Help—Rather Than Hurt—Midsize Galleries (And Other Insights)

From Art Basel to Christie's to the gallery world, our columnist weighs in on the ups and downs of new collaborations in the art business.

From Art Basel to Christie's to the gallery world, our columnist weighs in on the ups and downs of new collaborations in the art business.

Tim Schneider

Every Monday morning, artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, we consider stories that highlight the potential benefits of art market collaboration—and the surefire pitfalls of its absence…

Marc Spiegler. Photo: Mike Coppola/Getty Images.

On Monday, artnet News’s editor-in-chief Andrew Goldstein captained a deep-dive interview with Art Basel global director Marc Spiegler—one premised on the question of whether the industry’s highest-powered fair has become “the Facebook of the art world.” And while the interview’s release was scheduled in large part to kick off advance coverage of this week’s Art Basel in Hong Kong, the piece happened to go live just a few days after the Cambridge Analytica scandal exploded under the social-media giant like a grip of TNT strapped to the front axle of a mafia stool pigeon’s Benz.

But this unexpected turn of events also strengthened the urgency of what I found to be the most noteworthy theme in Goldstein and Spiegler’s exchange: Art Basel’s efforts to use its brand equity and resources to build a support structure for some of the galleries most vulnerable to the winner-takes-all 21st-century economy.

Although I presume this comment originally alluded to Facebook’s soul-searching in the aftermath of revelations about its role in Russian disinformation campaigns circa 2016, Spiegler could just as well have been talking about the social network’s public response to Cambridge’s data-mining antics when he related Art Basel to Facebook like so:

“Facebook is now starting to take responsibility for the impact of their platform. And because of the impact of our platform, we feel a responsibility towards sustaining the galleries that make our shows possible. I think it’s a sort of enlightened self-interest.”

The concrete result of this enlightened self-interest is that Art Basel is providing some of the same brand boosters for its smaller, younger galleries that the bigger, richer ones regularly bankroll for themselves.

Examples are helpful here. First, Art Basel now produces a physical catalogue on the fair’s “proposal-specific” sectors (like Statements, Discoveries, and Kabinett), so that the participating galleries have, in Spiegler’s words, something with “a kind of gravitas” that they can “give to collectors, and that remains after the show.” This is no small bonus, since physical catalogues in the art world A) basically function as sales books (and here, tangibly link smaller galleries to Art Basel’s prestige), and B) tend to be really f***ing expensive to do well.

The fair is building newer-school support structures, too. Spiegler mentions how, as of a few years ago, Art Basel began a permanent online archive covering every work uploaded to the fair by every exhibitor, in hopes that “in those tens of thousands of images there will lie a long tail,” i.e. an opportunity to sell (or resell) less in-demand works months or years after they’re actually shown at the fair.

In fact, Goldstein also notes in his preamble that the fair hired Jeni Fulton and Coline Milliard to help “create a new digital content layer” for Art Basel and its participants. It’s worth noting that this content layer now extends beyond text to video—another historically expensive and time-consuming endeavor. So the fair’s web page and YouTube channel now boast series like their bite-sized Meet the Gallerist featurettes, which, perhaps not coincidentally, highlight some of the scrappier exhibitors in this year’s Hong Kong edition.

Now, by no means am I saying “Happy Christmas (War Is Over).” Even if Art Basel were already doing all it could to lend a helping hand—which I doubt even Spiegler would claim, given how many times in the interview he emphasizes Art Basel’s willingness to evolve based on new information—the benefits would still only accrue to smaller galleries accepted to show at their fairs. That means only a few dozen anointed sellers, max, out of a field estimated to number in the low thousands.

And of course, even a full-on, industry-wide support system would arguably only double as a tarp concealing the larger, grislier question of whether it would be better to radically rethink “serious” art production’s default role as, to quote Anna Khachiyan’s searing truth bomb “Art Won’t Save Us,” “a glitzy barnacle on the side of global finance.”

Still, without more top-down support, the art industry increasingly seems headed for the worst of all possible worlds: one that worships profit as the one true god, yet simultaneously lacks an economic structure sound enough to even welcome a diverse congregation of artists and sellers into the temple. Art Basel isn’t the only entity, or even the only fair, that recognizes the problem. (Consider what NADA is doing for its smaller, dues-paying members.) But they’re the most powerful one experimenting with the most solutions. In bleak times, even imperfect light can point the way forward.

Christie’s CEO Guillaume Cerutti and his predecessor, Patricia Barbizet. Courtesy Christie’s.

On Friday, Melanie Gerlis of the Financial Times reported that Christie’s will add a collaborative new wrinkle to its Eastern sales strategy this year. The house has “invited three dealers to show and sell during its spring season of auctions in Hong Kong’s Convention Center,” from May 25–29.

The chosen trio consists of Robert Bowman, who will exhibit a selection of Rodin sculptures; Didier Claes, who will offer 19th and 20th century African tribal masks; and “animal sculpture specialist” Xavier Eeckhout, who will bring “several 20th century pieces,” including a €150,000 bronze elephant sculpture. (Hey, find a niche and own it.)

On one hand, Christie’s move can be seen as a heartening instance of cooperation across for-profit sectors. Quoth the house’s CEO, Guillaume Cerutti: “There’s this divide between auction houses and dealers, but they are some of our most important clients, and we should work together, particularly where we are growing a market.”

At the same time, Gerlis wisely points out that none of Christie’s gallery partners in this endeavor specialize in material that could clash with the lots in its slate of May auctions—perhaps a harder-edged variation on Spiegler’s “principled self-interest.” Not coincidentally, Gerlis also notes that all three dealers exhibited at this month’s TEFAF fair, where, by all accounts I’ve heard, Asian buyers were scarcer than good decision-making during the last stop of a pub crawl.

The larger question is whether Christie’s would be justified in taking an even more collaborative approach to future pop-ups. As Lisa Movius addressed in a recent feature for The Art Newspaper, some artists and galleries native to Hong Kong fear that the influx of high-powered Western sellers could cannibalize the homegrown arts scene. Even though Bowman, Claes, and Eeckhout are not the types of big black hats posing this existential threat on their own, they are still geographical outsiders. So it’s fair to wonder if their one-off partnership with Christie’s could cast the house as solving a Western problem at the cost of worsening an Eastern one.

If Christie’s shepherded two or three local galleries to the convention center alongside a few targeted European or American ones, though, could everyone, East and West, benefit from the brand equity? It seems plausible to me that the house could find a few Hong Kong dealers that would allow them to access lower price points—something auction houses have already been doing in various forms to help entice new buyers—without selling against their own inventory.

Then again, the idea may be too utopian or half-baked to explore any further. (I mean, it’s coming from a journalist who silently congratulates himself if he can snatch a piece of bread from the toaster oven without burning a finger.) But with Cerutti telling Gerlis that the spring pop-up will become an annual tradition in Hong Kong, Christie’s should have ample opportunity to evolve it in the years ahead. How much, and in what ways, they do so is worth watching.

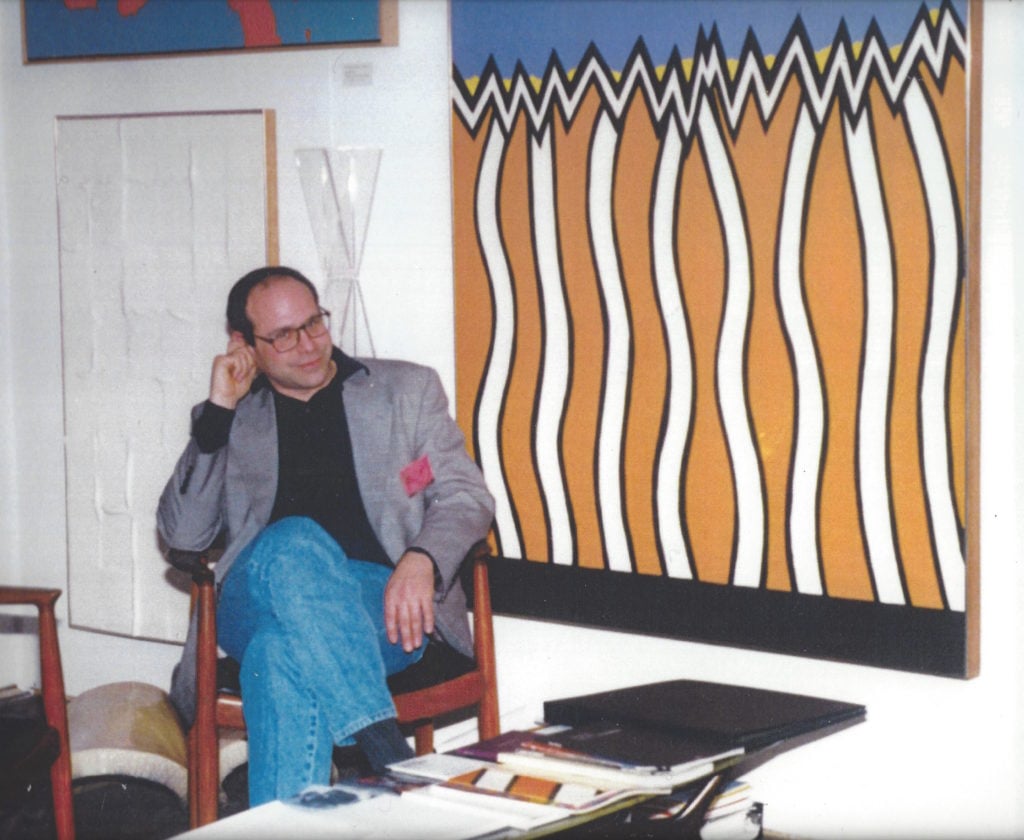

Mitchell Algus, circa 1998, in front of a work by Nicholas Krushenick.

Finally this week, on Wednesday, my colleague Rachel Corbett delivered an insightful (but sobering) profile of storied (but struggling) New York gallerist Mitchell Algus. Dubbing him the city’s “most beloved, least successful dealer,” the story doubles as a case study on why building a support ecosystem matters to everyone on the for-profit side of the art industry, not just the lower end of the proverbial totem pole.

Algus’s career typifies the unfortunate paradox in which a pioneering eye, a daring attitude, and a pure love of the game introduce the art world to work that makes a major critical and commercial impact—but not until some bigger entity co-opts it and, usually, shuts out its early champions. In most cases, the only reason you couldn’t say he was at the front of the line to show eventual stars like Barkley L. Hendricks, Betty Tompkins, and Lee Lozano (to name just a few) is that he effectively WAS the line. And all too often, the apex galleries have been the ones to enjoy the financial rewards of Algus’s boldness.

To me, the most memorable and instructive moment in the piece arrives through the lens of Lozano. Corbett tells of how Bob Nickas, a MoMA PS1 curator at the time, visited Algus’s 1998 exhibition of the artist’s “then-unknown” drawings, which Algus admits he was unable to sell at $1,500 each. Shortly after Nickas gave the late Lozano a survey at the museum in 2004, “Hauser & Wirth started representing Lozano’s estate and those drawings suddenly cost $65,000—‘the same drawings,’ Algus says.”

We all know this story. A bold gallerist takes a chance on an uncelebrated artist, but can’t crack the profitability code. Yet an influential actor from elsewhere in the industry encounters the artist through the gallerist’s money-losing efforts and puts the work on a bigger platform. The new scent of prestige wafts into the nostrils of a major gallery, which then swoops in and uses its brand equity to capitalize on what the bold gallerist couldn’t harvest themselves.

The major gallery gets rich. The artist (or their estate) gets rich. The influential intermediary gets lauded. And the bold gallerist gets nothing but a few kind words.

But what’s also clear from this exercise is that, absent the economic layer, the relationship between major players and small galleries is symbiotic, not antagonistic. The gallerists at both ends of the exchange deserve to benefit from the work they do and the resources they expend, just as the artist does.

But that’s not how the system works right now. Forget a rising tide lifting all boats. Instead, the sharks follow unwitting scout fish to a bountiful new food supply in uncharted waters. And instead of rewarding the scout fish for their efforts so the process can repeat to everyone’s benefit, the sharks monopolize the rewards and, intentionally or not, starve the scout fish to death.

This is how a food chain cannibalizes itself. And if high-end galleries continue Mitchell Algus-ing industrious smaller ones into oblivion, all levels of the art market will suffer.

That’s all for this week. ‘Til next time, remember: Just because we humans can shatter ecosystems doesn’t mean we have to be dumb enough to actually do it.