Art Fairs

Christian Viveros-Faune on Why Art Basel in Miami Beach Is Degrading for Art and Artists

The critic says the fair is like walking into your parents’ bedroom mid-coitus.

The critic says the fair is like walking into your parents’ bedroom mid-coitus.

Christian Viveros-Fauné

Gustave Courbet, The Meeting (Bonjour Monsieur Courbet) (1854)

In an 1854 painting called The Meeting, a young Gustave Courbet depicted himself encountering a rich art patron and his servant. Such was the legendary modern artist’s cocksureness that, in the picture, he sizes up the diminutive collector as if he were auditioning for a job as a PA. In Parisian art circles, the painting became known satirically as “Wealth Greeting Genius.” Today the roles of star and supplicant have been reversed. If you want to know how far we’ve come from the days when collectors came in for this sort of salutary abuse, then get yourself down to this year’s Art Basel in Miami Beach.

Art Basel in Miami Beach 2015

When the doors swung open for ABMB’s 14th consecutive V-VIP preview, the stage was set for what Friedrich Nietzsche—were he a hungry art consultant—would have called a strategic transvaluation of values. Tucked in among the scruffy press, the personal advisors, the hangers-on and the merely rich (sorry old-time collectors) were the show’s real artistes: the big money players (a.k.a., the art world’s Ken Griffins, Richard Changs and Steve Cohens) that magically transform blue-chip objets d’art into investment-grade assets like Apple stocks. No surprise here: At ABMB, the megawealthy rule—but they do so like at no other place on the planet.

The deck has probably never been so stacked against nettlesome, Courbet-like artists than at this year’s fair. According to economist Benjamin Mandel, the art market that Art Basel Miami sits atop is not part of the overall economy; instead, it’s part of the economy of a small subset of global Ultra High Net Worth Individuals (U.H.N.W.I.’s). These masters of the universe have, in their turn, remade the utilitarian Miami Convention Center into a massive NetJets lounge. Few places welcome difference or innovation less—producing its own outrages. Not only is ABMB 2015—in one famous painter’s definition of the shock of attending an art fair—like walking into your parents’ bedroom mid-coitus, it’s finding out they’re secret Mormons into the bargain.

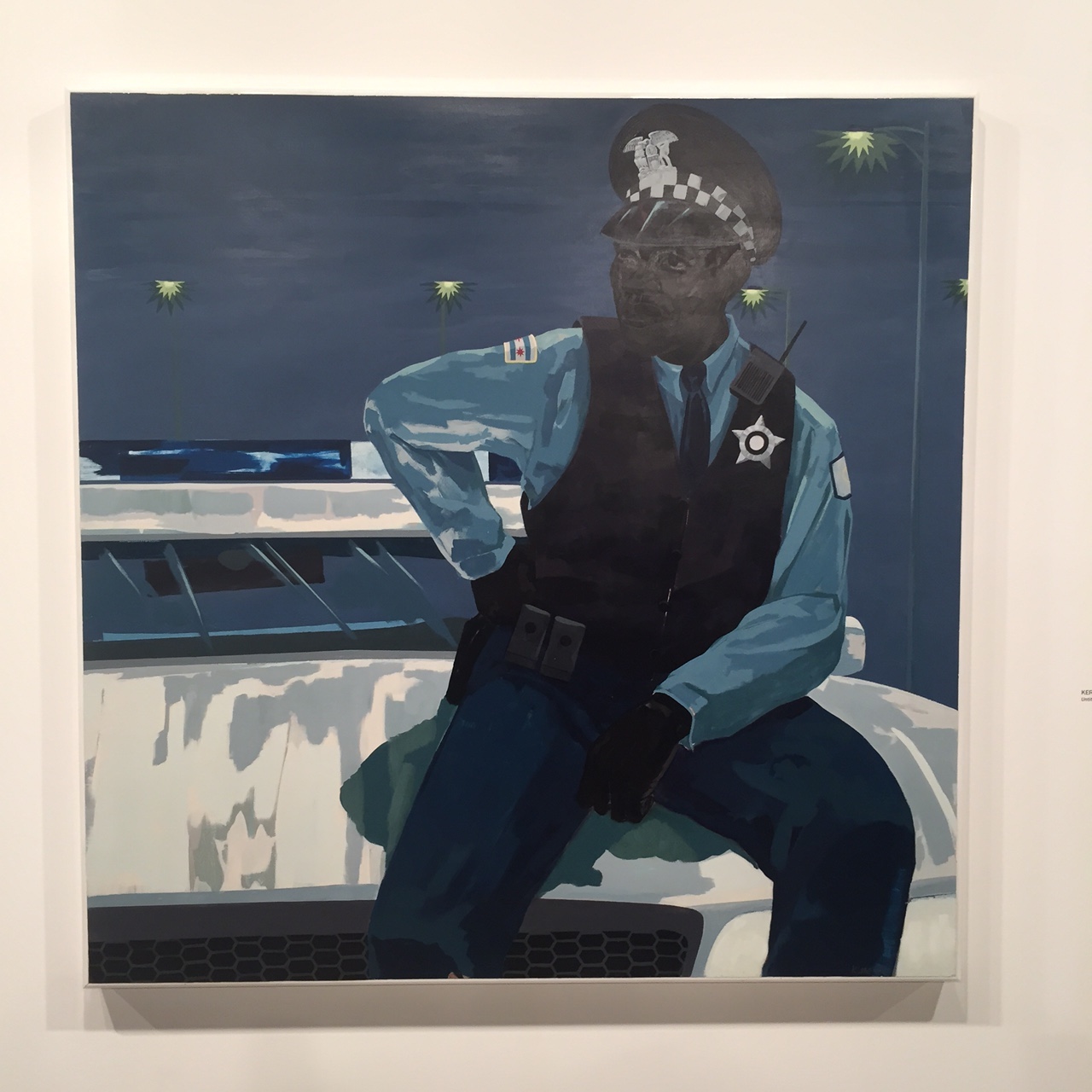

Kerry James Marshall, Untitled (Policeman) (2015) at Jack Shainman

Like November’s guarantee-laden auctions, this week’s brisk if somewhat sober sales at Basel Miami—as of this writing they included a $1.5 million Paul McCarthy sculpture (Hauser&Wirth), a $600,000 George Condo painting (Sprüth Magers) and a $300,000 Oscar Murillo scrawl (David Zwirner)—recount the latest chapter in the story of rising income inequality. This portion of the romance between art and money has been long in the writing, and is the culmination of a process started when speculative financial types took over where traditional collectors left off. Call it “Wealth Greets Genius Part II.” Not to give anything away, but it’s the part where the superrich demand artists make and exhibit highly conventional art in line with milquetoast aesthetics and reduced financial risk.

Another important finding among economists who study the effects of inequality on the art market is that wealth and incomes at the very top are “fractal.” What this means is that patterns repeat themselves at the upper end of the scale of wealth distribution, from the rich dentist (who is at the top 10 percent of earners) to the corporate CEO (top 0.1 percent) to the hedge fund manager (.01 percent). One result of this, according to The New York Times’ Neil Irwin, is that these patterns pump prices (and interest) skyward for works ranging from $30,000 Mel Bochner paintings to Picasso’s $179 million Les Femmes d’Alger. Yet one thing manages to hold steady: the bias toward received taste. Put another way: ABMB’s trend away from last year’s zombie formalism and toward this year’s auction-house approved material—Picasso Musketeer paintings at Galerie Gymurzynska, a Calder mobile at Helly Nahmad, a blue Andy Warhol Jackie painting at Richard Gray—still goes a long way to explaining the cultural conservatism built into global inequality.

Tracey Emin, Always More (2015)

Want more proof that the taste of collectors at ABMB 2015 is inherently conservative? Despite the presence of troublemaking pieces on the stands of a few choice booths—Kerry James Marshall’s portrait of black Chicago policeman at Jack Shainman, a piece of agitprop sculpture by Ian Hamilton Finlay at David Nolan, a smartly literate Dexter Dalwood canvas at Simon Lee—the vast majority of the stuff on view, irrespective of its quality, occupies a narrow bandwidth of well-heeled, mid-cult art appreciation. Up until now, ABMB had prided itself on being smart, edgy and sexy. Today it’s about as rousing as a corporate financial statement.

But it’s not just the surfeit of stuff repeating the most recent auction experiments—Italian Arte Povera here, the Japanese Zero artists there, and there, and there again—that tips one off to the rightward turn of contemporary collecting. It’s also the fact billionaire titans like Norman Braman and Ken Griffin are actively financing Republican candidates in both state and presidential elections. While the first is underwriting both the Miami ICA and Marco Rubio’s presidential campaign, the latter—the founder of one of the world’s largest hedge funds—recently contributed $5.5 million to the election of Illinois’ new union-busting governor. As Jeb Bush preps for Friday’s “Pop Art, Politics & Jeb” fundraiser in Miami Beach, it’s fair to say that, at present, contemporary art and Republican politics go hand in glove.

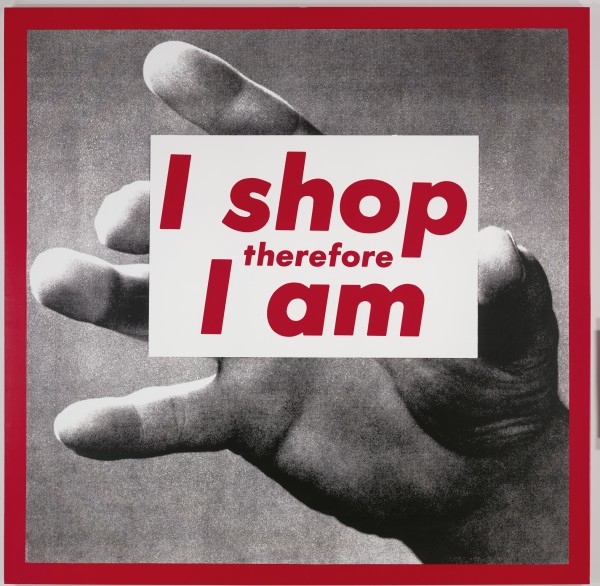

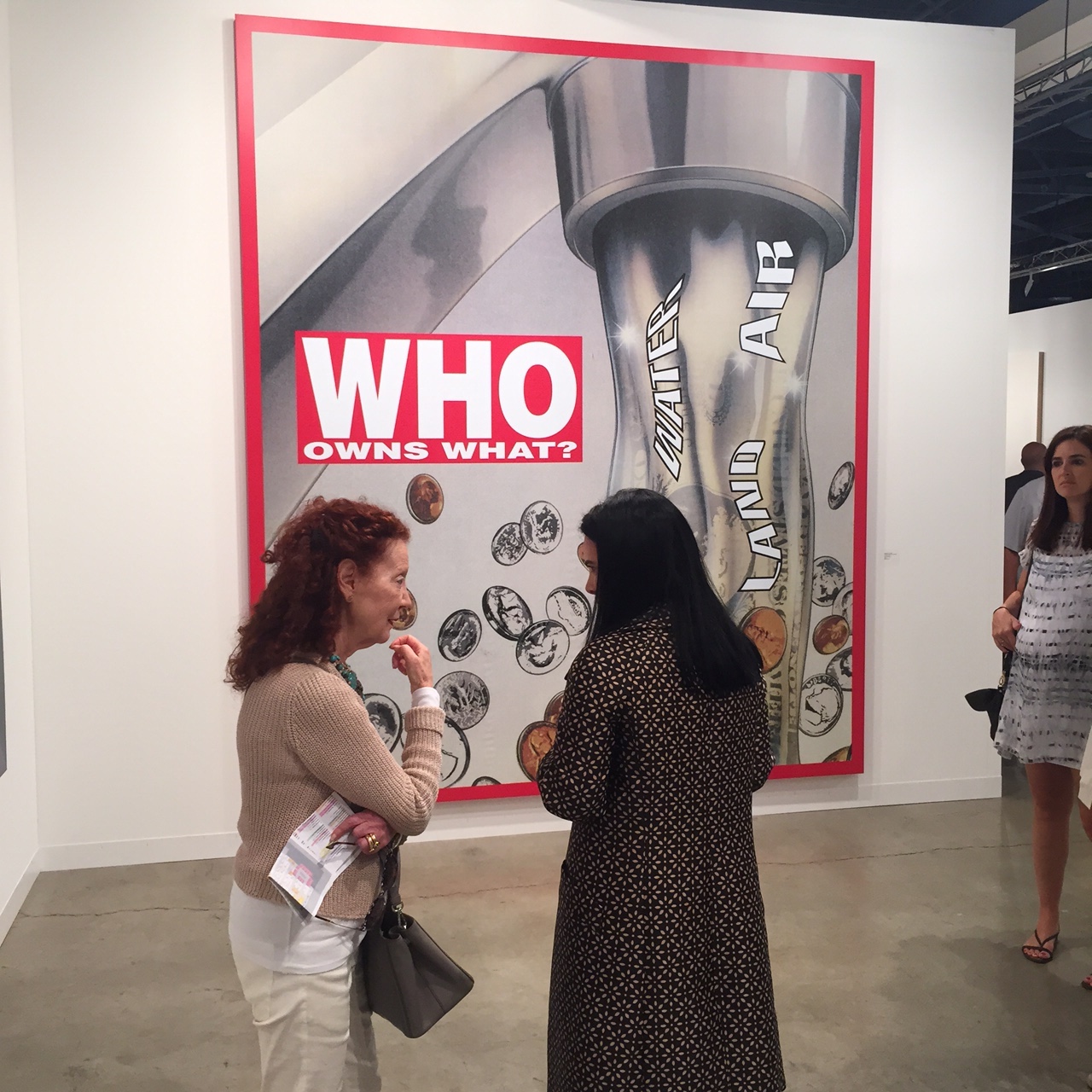

Barbara Kruger, Untitled (2015)

Even if one knows full well that fair-going is not supposed to provide anything akin to a radicalizing experience, folks are right to demand more from an event like ABMB. Sure sections like “Positions” and, especially, “Survey” go a ways to providing edge and gravitas to an affair that feels increasingly like shopping at the nearby Lincoln Road Mall, but they are tucked away into the corners of the convention center like a couple of independent bookstores. Still, there’s only so much blame one can place on fair organizers—they run a glorified trade fair after all. So, I say, blame the collectors, and along with them the dealers and artists who cater unquestioningly to the new financial overculture.

When Clement Greenberg wrote in 1939 that the avant-garde remains attached to the ruling class by “an umbilical cord of gold” he envisioned artists and others at one end ready to yank the blingy chain. At ABMB, important exceptions noted, there appears to be almost nobody. Courbet is spinning in his grave.