In February last year, a group of art-dealing titans went public with an unusual proposition—they would team up and sell the storied collection of the late philanthropist Donald Marron. The move was a shock to the art-world system because it saw three galleries, Gagosian, Pace, and Acquavella, snaffling up a $450 million estate that historically would have been the territory of auction houses.

The Marron deal was a strong sign that the traditional lines separating galleries and auction houses had become increasingly blurry. This slow-brewing convergence only accelerated after the pandemic struck, when both sectors were initially confined to the web.

Now, as auction houses pursue pop-up spaces and invest in private sales while galleries launch new secondary market ventures, the market’s Venn diagram threatens more than ever to become a circle.

Welcome to the era of the blobified art market.

Sotheby’s new space in Palm Beach. Image courtesy Sotheby’s.

What Is at Stake?

The business model of auction houses has historically hinged on splashy and expensive public sales of work by dead artists and from collectors’ estates. Meanwhile, traditional dealers would more quietly sell work on both the primary and secondary markets.

But these divisions have been eroding for years. Sotheby’s began experimenting with the private-sales model as far back as the early ’90s. Meanwhile, Christie’s acquired a primary market gallery, Haunch of Venison, in 2007, which dissolved six years later to become its private-sales arm.

Amid a dip in confidence in public sales during the pandemic, auction houses reported record highs in private transactions. The Big Three houses—Sotheby’s, Christie’s, and Phillips—all saw the category grow around 50 percent in 2020.

Auction houses have also taken on a greater interest in exhibition-making, buying up or renting out more space to mount exhibitions, conduct private sales, and organize selling shows. Last year, Sotheby’s opened pop-up gallery spaces in Palm Beach and East Hampton, and the house is now moving its Paris headquarters into the former premises of the legendary Bernheim Jeune gallery.

David Nash, cofounder of Mitchell-Innes & Nash gallery who previously led Sotheby’s contemporary and Impressionist and Modern art divisions, regrets his role in encouraging the house to take up private sales, as he now sees the development as an existential threat to galleries.

“I don’t know how dealers can respond to it,” he tells Artnet News. “Certainly the auction galleries have taken away huge amounts of business… and the number of dealers who were really involved in the resale market have shrunk.”

Art advisor Sibylle Rochat thinks auction houses’ posture threatens to cut into galleries’ business with living artists as well. “Galleries are losing control of the secondary markets of their artists and unfortunately this is where they could make the money to grow, meaning there is a glass ceiling for galleries working with living artists,” Rochat says.

From left to right: Arne Glimcher, Bill Acquavella, Larry Gagosian, and Marc Glimcher. Photo © Axel Depuex.

Galleries Muscle In

Yet blobification is not a story of one sector engulfing another—both sides are encroaching on the other’s turf. In the process of handling the Marron estate, the three mega-galleries launched a new business called AGP to handle future sales of major collections.

The move has received nods of approval from other respected dealers—including Emmanuel Perrotin and Johann König, who are among a cohort testing out secondary market endeavors of their own. While their projects are distinct, they share a common desire to dip into auction-house portfolios—and to do business with margins higher than the typical primary market 50-50 split between artist and dealer.

Perrotin, who recently opened Perrotin Second Marché with two business partners, says that his gallery’s presence in a five-story building down the road from Christie’s and Sotheby’s on Avenue Matignon is “sending a powerful message that our presence is wished for and founded on expertise.”

Galleries’ push into the secondary market is in part a response to the fact that artworks are cycling through collections much faster than they used to, he says: “Works now can appear twice within five years without affecting its value—to the contrary. Collectors have come to realize that it could be in their interest to work with [artists’] galleries on both the buying side and the selling side.”

Back in 2011, when White Cube became one of the first galleries to venture into secondary-market dealings with a dedicated gallery (run by the now-disgraced dealer Inigo Philbrick), the prospect was taboo enough that White Cube gave it a different name, Modern Collections.

Last month, White Cube launched a new venture under its own brand, Salon, to offer month-long presentations of individual secondary market works. The initiative began with a work by Carmen Herrera, who is not represented by the gallery.

The aim, according to Mathieu Paris, White Cube’s director of private sales, is to distinguish itself by foregrounding scholarship and expertise. “Auction houses are playing the clock and the quantity of sales whilst galleries are proposing more elaborate curatorial visions,” he says.

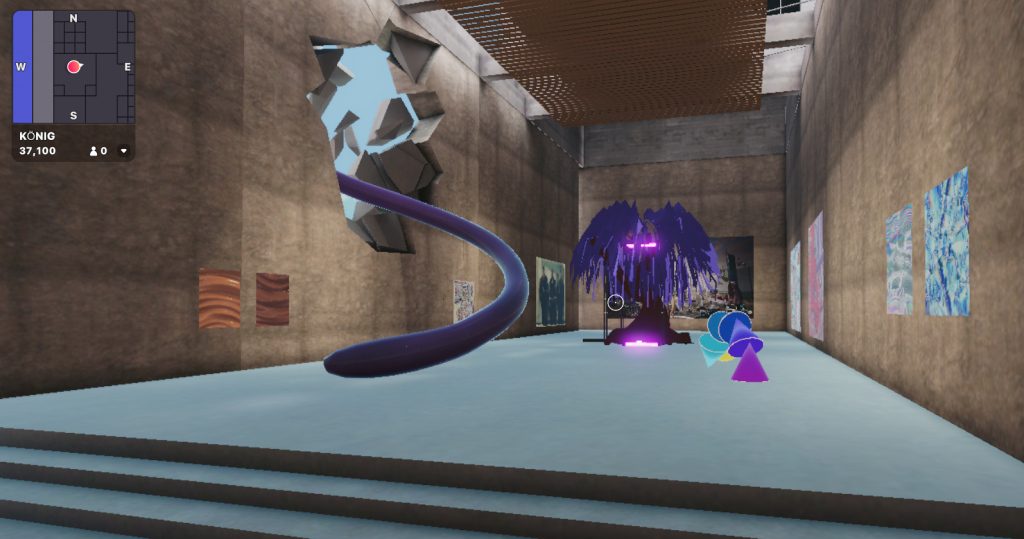

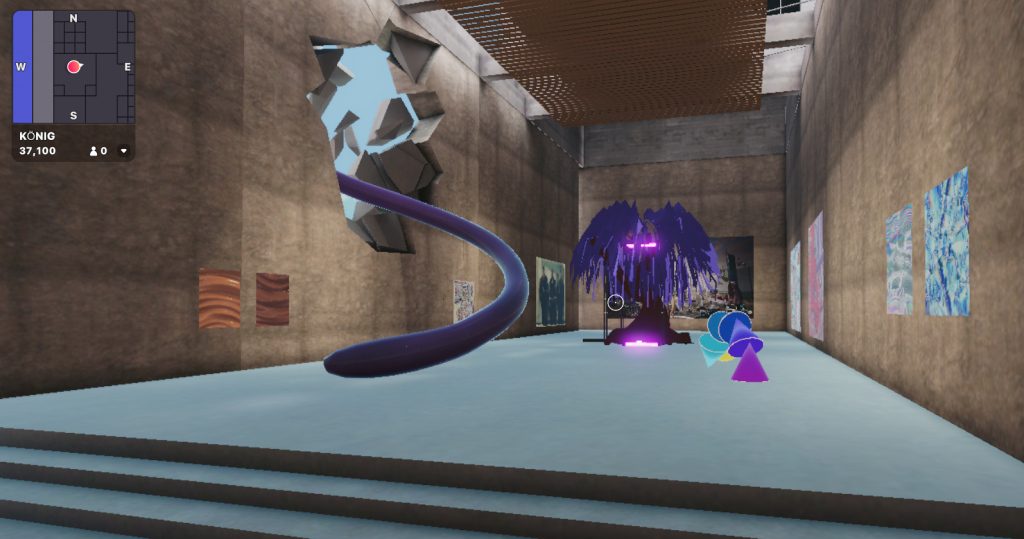

A scene inside König Galerie’s virtual show on Decentraland, which was accompanied by the gallery’s first-ever auction. Courtesy of KÖNIG GALERIE.

Other dealers are less interested in making any distinction at all. “If you are client-centric, there is no separation between [auction and gallery] models,” Johann König tells Artnet News. He has been trying out both an in-house art fair and, more recently, an auction with digital works attached to artist-minted non-fungible tokens (NFTs).

Indeed, the vogue for NFTs has likely accelerated blobification even further. Crypto-artists, König notes, seem to place less value on galleries’ vetting clients and placing work, forcing dealers who are eager to get in on the action to adopt a new approach. “They find it the most normal thing in the world to auction off their work,” he says. “How crazy is that?”

The new Perrotin gallery in a five-story townhouse at 8 Avenue Matignon in Paris. L’ATELIER SENZU.

What Is the Future of Blobification?

The convergence between auctions and galleries is already having an impact on transparency. While online art fairs and viewing rooms have encouraged galleries to share prices publicly, the increased volume of and new formats for online auction sales have resulted in increasingly obscure public results.

Some question whether auction houses might end up undermining their own business model by delving into private sales and other strategies borrowed from galleries. Several experts commented that even live auctions, with the omnipresence of in-house and third-party guarantees, have become little more than private sales conducted theatrically in public. “I’m not quite sure whether they are swallowing their own tail,” dealer David Nash says.

Some houses have been reluctant to embrace guarantees for this very reason. “In principle, you put something in an auction and it either sells or it doesn’t—so if one starts using mechanisms like guarantees, it would contradict what one is trying to do in an auction,” says Diandra Donecker, a director and partner at Grisebach auction house in Berlin.

Denzil Forrester in conversation with Victor Wang, LIVE, Frieze Week 2020

Photo by Deniz Guzel. Courtesy of Deniz Guzel/Frieze.

One aspect of the gallery business that auction houses have not subsumed is the representation of artists and estates, which is generally a longer-term commitment than these businesses—which have seen significant turnover in recent years—are suited for.

Sotheby’s quietly shuttered its artists’ estates division in 2018 after less than two years, and its plan to co-represent the estate of Vito Acconci never got off the ground. But David Schrader, the house’s global head of private sales, noted that some artists may become increasingly open to selling directly through auction houses and bypassing the gallery system entirely. “I think ultimately that’s sort of where we’re going with NFTs, that’s essentially a direct-to-market strategy,” he says.

Schrader predicts that the era of blobification has only just begun, and that the market’s future lies in multi-faceted art businesses rather than strictly defined auction houses or galleries. The stress of the pandemic encouraged sectors to collaborate, with some galleries even offering inventory (gasp!) on auction-house websites. “I do think that there is a softening of old boundaries-slash-adversarial type thinking,” he says.

According to Schrader, Sotheby’s data shows there is only a five percent overlap between private-sales clients and those who are active in auctions, but those who cross over from auctions to private sales don’t reduce their activity in the former category. “There’s an historical myth of cannibalization of one versus, the other,” Schrader says. “And in fact, I think they’re quite synergistic.”

Nora Turato, “let’s never be like that”, organized by LambdaLambdaLambda, LA MAISON DE RENDEZ-VOUS, Brussels, 2020. Photo: Isabelle Arthuis.

The result may be art businesses that not only look more and more alike, but also converge on the same moments and locations. Asked whether he could imagine an auction at Art Basel in the future, Schrader didn’t rule it out: “I think if you asked that question two years ago, the answer would have been, zero chance. And I think if you ask the question today, it might be 25 percent.” He points out that for years Sotheby’s mounted exhibitions in the same building and during the same week as Art Basel in Hong Kong.

Despite the possibilities, not everyone is likely to emerge from this blobified art market a winner. In an industry of vertically integrated conglomerates, what happens to emerging and mid-range dealers?

“Galleries can learn from auction house strategies,” says Jo Stella-Sawicka, the London director of Goodman Gallery, which teamed up with several other dealers on an experimental auction to help uplift artists and galleries in the Global South, “but not everyone has the medium or the means to do that.”

Jeffrey Rosen, who cofounded the Brussels gallery-share Maison de Rendezvous in Brussels, is skeptical that centralization is good for culture. “What we put on the walls must be dictated by the belief that it has cultural significance in the immediate present while betting on it in the long-term,” he says, and “not determined by what will generate the most money as quickly as possible.”