Auctions

The Biggest Winner of Auction Week and 12 Other Takeaways From New York’s $2 Billion Sales

From the biggest winner to the most surprising pass, here are our parting observations from last week's auction marathon.

From the biggest winner to the most surprising pass, here are our parting observations from last week's auction marathon.

Artnet News

A knee-buckling $2.04 billion in art traded hands during a 13-auction flurry at Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Phillips last week. The individual sales in that tally spanned the usual Impressionist, Modern, postwar, and contemporary categories, as well as special sessions dedicated to the collections of Barney A. Ebsworth (at Christie’s) and Nelson and Happy Rockefeller (at Sotheby’s). And yet the grand total still fell beneath last November’s $2.3 billion giga-week, though the history-making $450.3 million boost provided by the record sale of Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi played a huge role in that bonanza.

With hundreds of lots and untold thousands of bids competing for attention, it can be overwhelming for any market professional or curious observer to leave last week with a firm grasp of what exactly happened, let alone what it all means going forward. Fortunately, artnet News’s trusty auction team sorted through the madness to offer you 13 takeaways from their joint coverage of the Big Three’s evening sales.

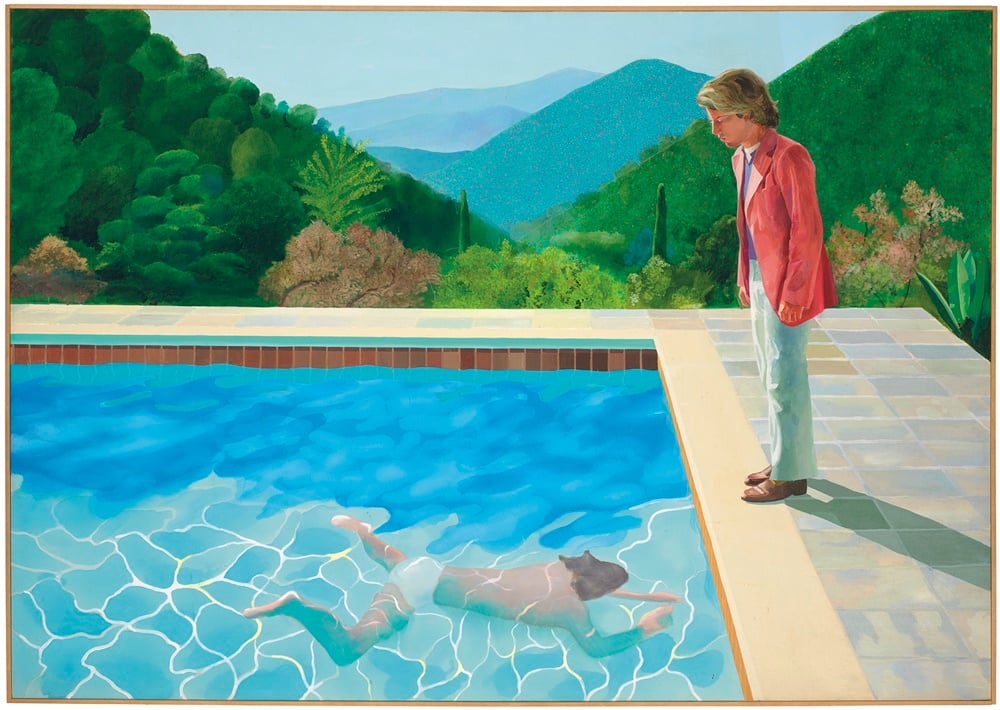

Bidding for David Hockney, Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures) (1972). Courtesy of Christie’s Images Ltd.

Who sold the most by sheer volume last week? That mantle goes to Christie’s—again. The privately owned auction house notched $1.09 billion in sales (or $1.1 billion if you include several supplementary, dedicated sales held last week of work by Giacometti and Picasso), Although that total is down from the $1.42 billion worth of art it sold in the equivalent slate of sales last fall (which, must we remind you, included that hefty $450 million painting you’ve heard so much about), it still led Christie’s to outpace rival Sotheby’s. The publicly traded house earned $835 million last week, up considerably from its equivalent total of $724 million last year. Meanwhile, Phillips, which held two sales, came in a distant third with $114.1 million, down from $134.6 million last year. (One caveat: These totals represent the sheer dollar value generated, but do not account for any losses incurred from deals with third parties or other financial machinations. So the final balance sheets from the week may look a bit different from what you see here.)

Phillips, long known as a reliable source of contemporary work, took a new tack this season by offering more modern fare than it usually does. But it struggled to sell big-ticket paintings by Alberto Burri and Jackson Pollock at its 20th century and contemporary art evening auction last week. The tactic’s flat-footed landing reinforced the truism that timing is everything. Phillips, which rolls the two categories into one unlike its competitors, is in the unfortunate position of having to follow Christie’s and Sotheby’s Impressionist and Modern sales.

Perhaps clients that came to New York to shop for Modern art already found what they were looking for at Phillips’s competitors. Or maybe they wanted to keep their powder dry ahead of Christie’s contemporary sale, which typically begins just minutes after the Phillips sale finishes. Either way, the schedule proved challenging.

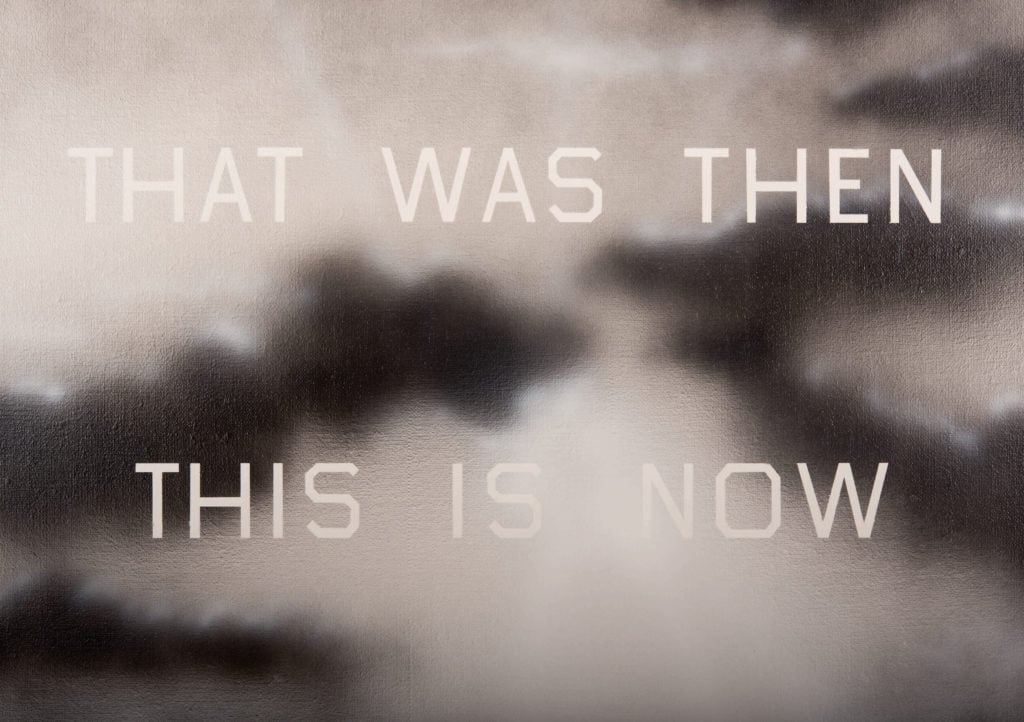

Ed Ruscha, That Was Then, This Is Now (1989). Image courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Although this November’s sales delivered a few (very) high-dollar records, the healthy cumulative totals arrived with relatively minimal froth. Bidders by and large seemed intent on hunting for value and refusing to go overboard, even for works marketed as the cream of any given auction’s crop. (If you want an example, see the next item.)

Were pre-sale estimates especially on point? Did a surplus of quality works prevent buyers from clustering around a handful of special lots? Or has the collector base, so often vilified for its excesses, learned from past mistakes in more exuberant market cycles? Opinions vary widely enough to keep the discussion lively until Art Basel Miami Beach, the next (and last) market milestone of 2018.

Vincent van Gogh, Coin de jardin avec papillons (1887). Courtesy of Christie’s Images Ltd. 2018.

It’s never a good look when a sale’s would-be star lot flames out before reaching the reserve price, and each of the Big Three houses met this ignominious fate in an evening auction this past week. At Christie’s Impressionist and Modern evening sale, Vincent van Gogh’s Coin de jardin avec papillons (1887) carried an unpublished presale estimate in the region of $40 million, but the work was bought in at $30 million. At Sotheby’s Impressionist and Modern sale the next night, Marsden Hartley‘s Pre-War Pageant (1913)—hyped by the auction house as the “most important work of American modern art ever to appear at auction”—passed at $24 million against a low estimate in the region of $30 million. And for the cover-lot anticlimax at Phillips’s 20th century and contemporary evening sale, see below.

Phillips offered a beautiful, petite, and rare Jackson Pollock drip painting once owned by Nelson Rockefeller and controversially consigned to Rio de Janeiro’s Museum of Modern Art. Despite the illustrious provenance, accommodating scale, and scarcity of comparable works on the market, the work failed to reach the reserve price. (It’s estimate was in the region of $18 million.) Not to be deterred, however, Phillips’s CEO Ed Dolman told artnet News after the auction that the painting was just one bid shy of selling, and that the house would seek to make a deal with the underbidder in a post-sale arrangement.

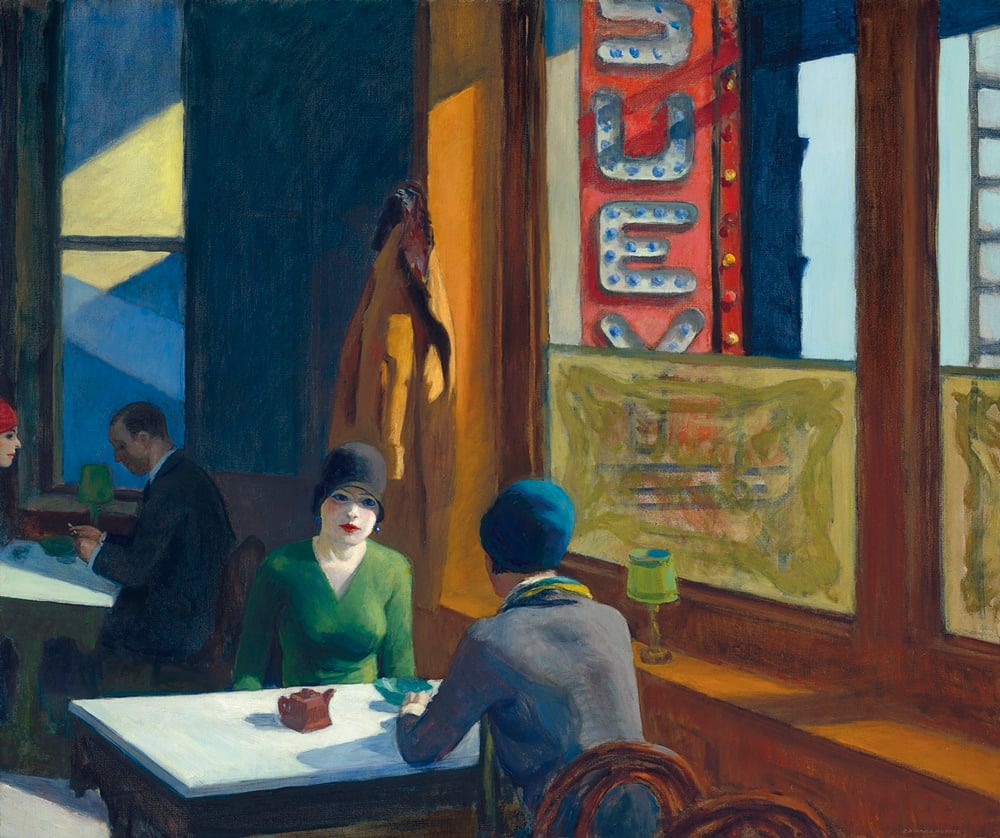

Edward Hopper’s Chop Suey (1929) sold for a record-setting $91.9 million in Christie’s evening sale of the Barney A. Ebsworth collection. Courtesy of Christie’s Images Ltd.

Good provenance is always in fashion. And both Sotheby’s and Christie’s continued leaning hard into the strategy of presenting blocks of works by esteemed collectors this fall. Sotheby’s fronted its contemporary evening auction with the next installment of its David Teiger collection sale, which will be parceled out over forthcoming auctions throughout 2019.

Christie’s, though, arguably took matters to a new extreme. It set records through its Barney A. Ebsworth collection sale, partly framed its postwar and contemporary auctions around works sourced from Harry W. and Mary Margaret (AKA “Hunk” and “Moo”) Anderson, and even made “Great Collections” the unifying theme of its Impressionist and Modern evening auction. (The latter included works from the holdings of Herbert and Adele Klapper, Sam Rose and Julie Walters, Elizabeth Stafford, Eugene V. Thaw, and A. Jerrold Perenchio.)

David Hockney, Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures) (1972). Courtesy of Christie’s Images Ltd.

The uncharacteristic absence of a financial guarantee, the unprecedented elimination of a reserve price, the unceasing question about how much of the buyer’s premium Christie’s may have passed through to the consignor—all of these elements (and more) made the house’s handling of Hockney’s masterpiece the most gossiped-about consignment of the fall sales cycle. And now that the painting’s sale for a premium-inclusive $90.3 million gives Hockney the title of most expensive living artist at auction, one more unsolved puzzle can be thrown into the playpen: Who bought it?

Georgia O’Keeffe, Calla Lillies on Red (1928). © 2018 The Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

True to the auction sector’s growing sense of borderlessness between genres, Christie’s and Sotheby’s jointly created the trade’s next “Bob Dylan goes electric” moment by positioning O’Keeffe’s work in their respective contemporary evening sales (as opposed to its typical home in the American art category). The results were relatively underwhelming, as all three works hammered at or beneath the low estimate.

Calla Lilies on Red (1928), one of the paintings consigned to Sotheby’s by the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, saw the most dramatic under-performance. Bidding reached only $5.3 million against an $8 million low valuation. (The price with premium settled just below $6.2 million.) However, O’Keeffe’s time traveling experiment may have been less responsible for the modest tallies than oversupply. All told, nine of the artist’s works mounted the auction block in New York within a week.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Masque (1981). Image courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Forty-eight lots into Sotheby’s contemporary evening sale, the last of four Basquiat works on offer hit the block: Masque, a domestic-sized canvas centered on a crowned crimson head. After a modest volley of bids lasting about two minutes, the piece hammered at $3.85 million, just below its $4 million high estimate. Within earshot of the press row, the winning bidder reported to his phone client, “Got it! It’s yours. Good luck. Love you, too.” Who says there’s no genuine affection in an auction room?

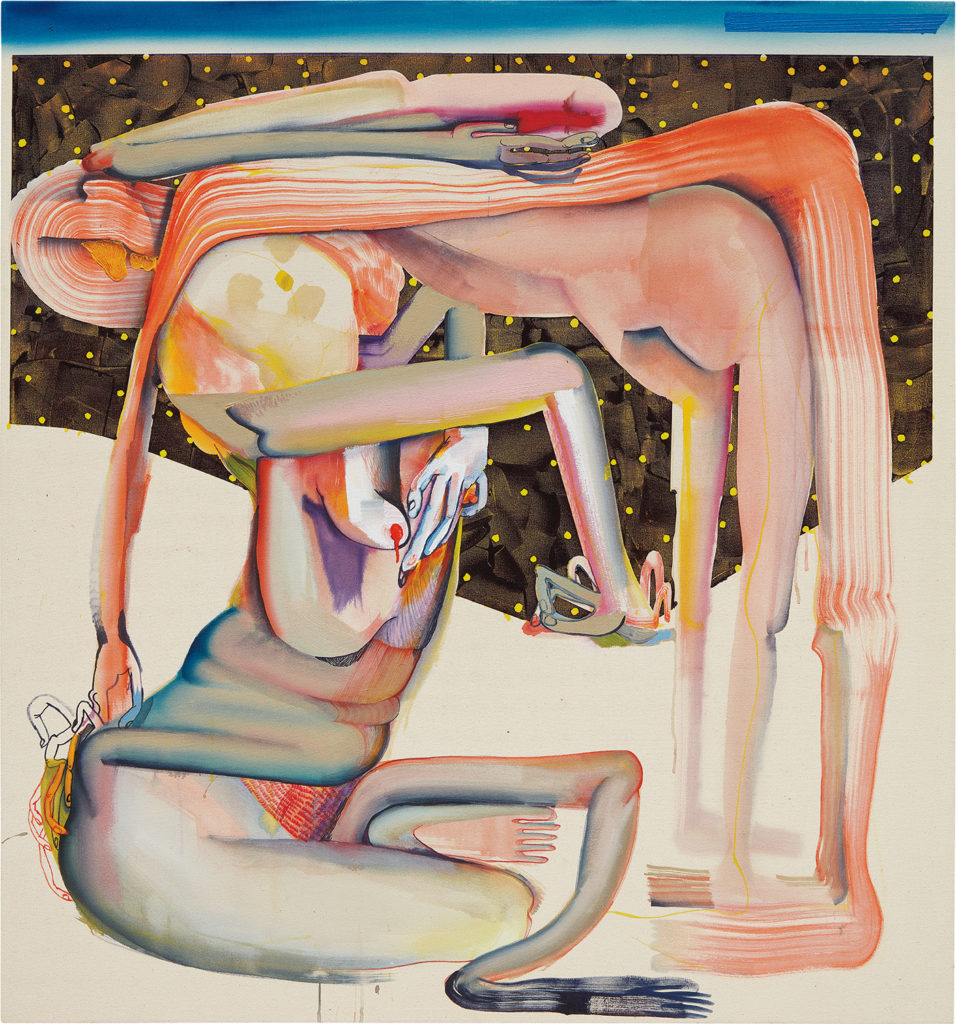

Christina Quarles’s Pull on Thru Tha Nite (2017).

It’s almost as if you could still smell the oil paint on 33-year-old American artist Christina Quarles’s Pull on Thru Tha Nite (2017) when it went under the hammer at Phillips’s evening auction on Thursday. That’s because it went from the studio to the salesroom in under a year. (It was originally sold at David Castillo Gallery in Miami.) This also marked the first time a work by the artist was included in a major evening sale. But the newness appeared to give it a boost: the painting ended up selling for $225,000, well over its $50,000 high estimate.

Rembrandt Bugatti, Deux Girafes (1906–7). Image courtesy of Sotheby’s.

While some collectors flip works faster than pancakes, others hold on for decades before reselling. At Sotheby’s Impressionist and Modern sale, Rembrandt Bugatti’s Deux girafes (1906–7) sold for $1.8 million with premium on a pre-sale estimate of $1.5–2 million. It had been owned by the same family since 1908. The French author Joseph Reinach bought it from Paris’s Galerie Adrien A. Hébrard the year after it was made; it was consigned to auction by his descendants.

The market for Cuban-American painter Carmen Herrera has been on a long overdue rise. At Phillips on November 15, Blanco y Verde (1966) sold for a record $2.6 million, nearly $1.5 million more than the 103-year-old artist’s previous record of $1.8 million, set for Untitled (Orange and Black) (1956) at Phillips last November.

Meanwhile, years of steadily rising interest in the work of African American painter Sam Gilliam hit something of a crescendo in recent years and the intense attention—including a solo exhibition at the Kunstmuseum Basel—is well deserved. At Christie’s postwar and contemporary evening sale on November 15, a new record was set for Gilliam when Lady Day II (1971) sold for $2.2 million. This marks a price spike of around $1 million over the previous record of $1.2 million, for FORTH (1967), sold at Sotheby’s London this past June.

We’ve all seen what happens when auction-house marketing campaigns go into overdrive. But while there was little marketing firepower behind the work of street artist KAWS, he had a remarkably strong week. He saw two new auction records set—one for painting and one for sculpture—at Phillips in the same night. Untitled (Fatal Group) (2004) sold for $3.5 million, pulverizing its estimate of $700,000 to $900,000. A little over 20 lots later, Clean Slate (2014), a large mixed-media sculpture, fetched just under $2 million. And later that night at Christie’s, another KAWS painting, Chum (2012), scored $2.4 million amid intense bidding, particularly among specialists who work with Asian clients, leaving the $300,000 to $500,000 estimate in the dust.

What gives? “KAWS’s market really found its foundation and evolved in Asia,” Amanda Lo Iacono, head of Phillips evening sale, told artnet News. “The Asian collector base is less snobbish about artists whose art is commercialized. KAWS was coming through more of a street-art vein and an illustrator background. He didn’t have an issue with his art having a commercial-leaning tendency.”

This is somewhat counter to the way elite artists often enter the market’s upper echelon through high-end galleries. Now, says Lo Iacono, the universality of the subject matter, derived as it is from cartoons, is striking a chord. “It doesn’t matter what language you speak, there is a nostalgia factor to his art,” she says.