Auctions

Is the Contemporary Art Market Due for a Contraction? A Look Beyond the Mega-Sales Presents a Dimmer Picture

Contemporary art was the only major category to decline in total sales volume at auction last week. Here's what that means.

Contemporary art was the only major category to decline in total sales volume at auction last week. Here's what that means.

Tim Schneider

It’s not a world-shaking revelation that the auction market operates at a decidedly higher price band than the gallery market. Spending enough cash to make you a gallery VIP might not rescue you from a seat assignment in Sotheby’s overflow room. But with plenty of top-tier collectors gearing up for Art Basel Miami Beach and a vanguard of high-level dealers bringing enough blue-chip resale work to fill a private museum, it would be naïve to assume the results of this November’s premier auctions may not be instructive for the private market’s last major event of 2018.

This is especially true if we restrict our focus to the more trade-savvy daytime sessions. So in the all-too-brief lull between New York fall auction week and Miami art week, I combed through the sales data from the former to see if it might reveal any useful trends to watch during the latter. Here’s what the day sales at the Big Three had to say this year, courtesy of my colleagues at the artnet Price Database and artnet Analytics Reports.

The upshot: Outside the realm of trophy works, contemporary art did not perform as well as it has in the past. And that—combined with grim projections about where the economy is headed—may take the market in a conservative direction.

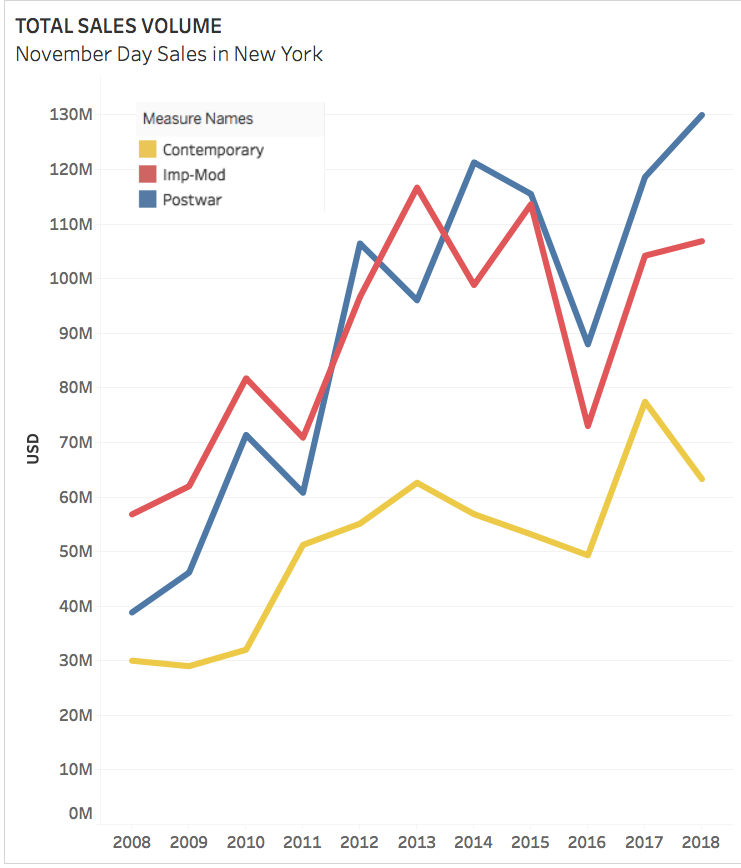

The total amount of money generated by contemporary work (which we define as made by artists born in 1945 or after) in the day sales dropped to $63.3 million from its peak of $77.4 million last year. In contrast, postwar rose from $118.6 million to nearly $130 million, and Impressionist and Modern climbed from just over $223 million to almost $231 million.

What does it mean?

Activity in the more reasonably priced day sales is considered a strong indicator of the trade’s direction (because dealers and traders often buy work there to resell at a higher price later). So one might surmise that the trade saw greater upside in more time-tested categories of works this November. It’s also possible that buyers regarded the most expensive contemporary works as the best bets, which would explain why the total sales value of contemporary works in the evening auctions outperformed expectations, rising by about one-third year over year against a 13-percent year-over-year drop in total pre-sale low estimate value.

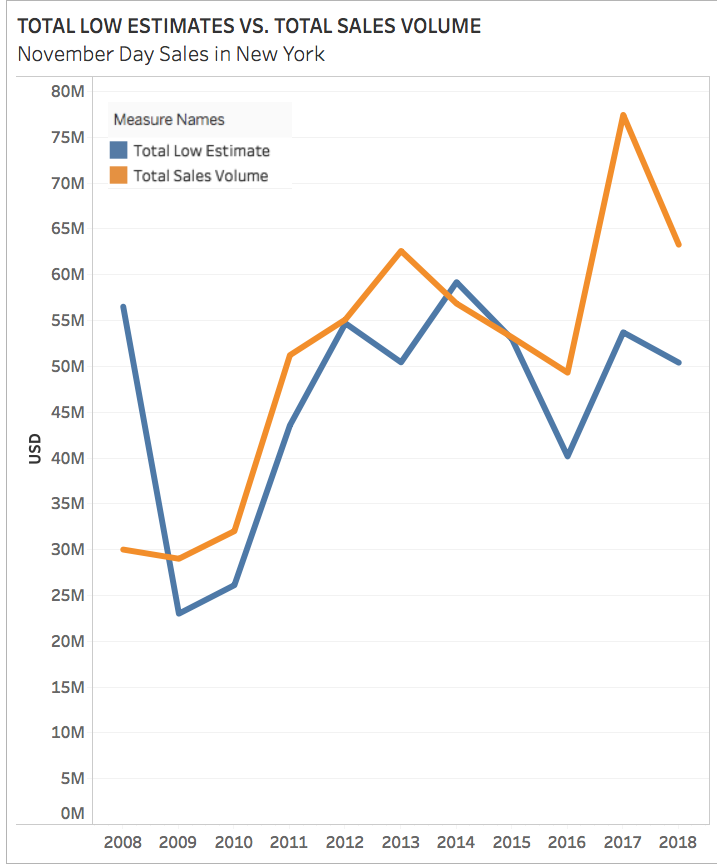

Based on pre-sale estimate data, Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Phillips expected the category to decline in value during their November day sessions compared to the equivalent sales last year. But total sales volume of contemporary works in the day sessions nosedived roughly 18 percent year over year, a fall three times as steep as the six-percent year-over-year decline in total pre-sale low estimates.

What does it mean?

Since the houses’ job is to anticipate market moves before they happen—Loïc Gouzer once compared the task to meteorology—Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Phillips collectively saw signals that buyers were retreating from contemporary weeks, if not months, in advance of auction week. Yet buyers appear to have reacted even more aggressively to the same signals (perhaps influenced by the additional time between the auction catalogues’ release and the sales themselves), leading to a sharper rate of decline versus 2017 than the specialists anticipated with their estimates.

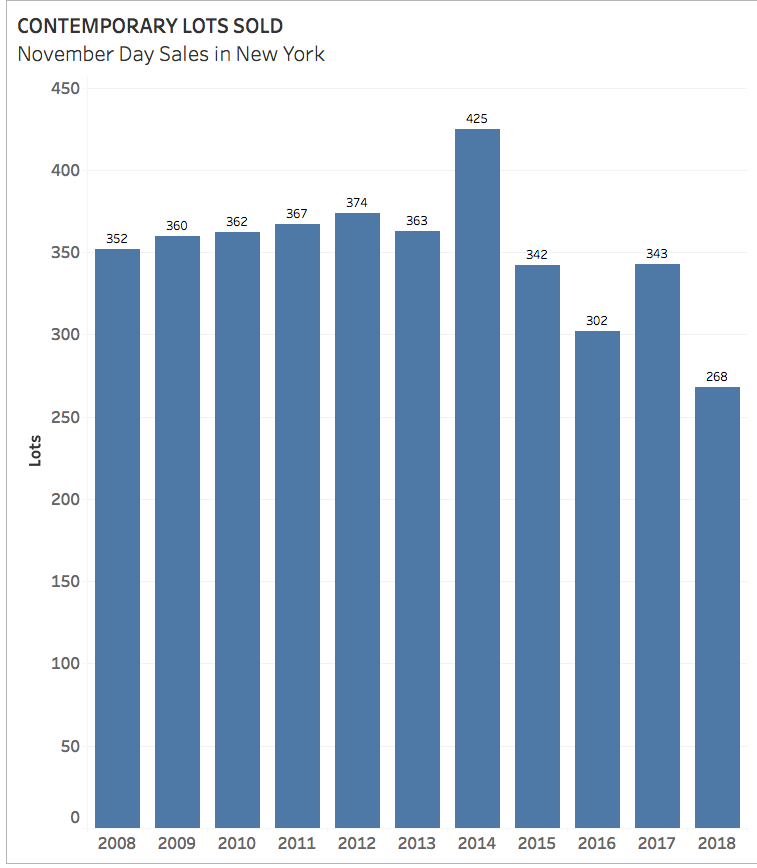

Only 268 contemporary works sold in 2018’s daytime sessions. This is both an all-time low and less than two-thirds as many lots as at the category’s peak four years ago, when, not coincidentally, the frenzy for young process-based abstractionists crested. The number of lots offered year over year has also decreased almost in lockstep with the number of lots sold since the 2014 peak, reaching a new low of just 320 this November.

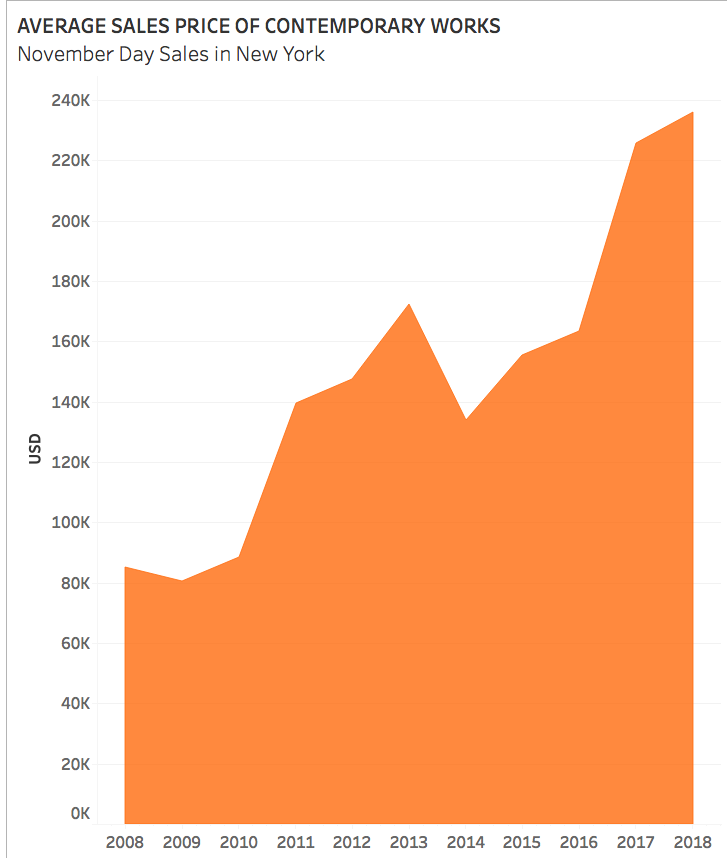

But with an average sales price above $236,000, contemporary lots in the daytime auctions were more expensive than ever this November. In fact, they were nearly triple their counterparts in day sales a decade ago, when the average sales price in the category hovered just above $85,000.

What does it mean?

Since the average price of contemporary works in day sales generally continued to rise over the past decade even when the number of lots sold increased, this November looks less like a story of higher prices caused by uncharacteristically low supply than a story of a stagnant (or shrinking) pool of contemporary buyers continuing their long-running tendency to pay a premium for quality.

Combine the findings from these four charts, and what might they suggest about the bigger picture?

Alex Rotter and Loic Gouzer conferring at the height of the phone-bidding during the evening sale at Christie’s. Eduardo Munoz Alvarez/Getty Images.

Let’s think back through the mini-conclusions above. In the generally more circumspect daytime auctions, contemporary works’ total sales fell while postwar, Impressionist, and Modern works’ total sales continued to rise. The houses expected contemporary works to decline this November based on the estimates they published before the sales, but by the time the auctions arrived, buyers reacted even less enthusiastically than the houses anticipated. A historically low number of contemporary works were offered and sold, while their average sales prices were historically high.

Broader economic context seems relevant here. As relayed by the Wall Street Journal last week, at least one metric projects that both stocks and bonds will have been money-losing investments when 2018 closes. That hasn’t happened in 25 years. In addition, “90 percent of the 70 asset classes tracked by Deutsche Bank are posting negative total returns in dollar terms for the year through mid-November.” That is the most gruesome result since 1901. Financial adviser and writer Josh Brown summed up these signals by declaring 2018 “The Year No One Made Money.”

It’s entirely possible that I’m reading too much into things. But if you, like me, believe that the art economy is almost always a reflection of the larger economy, then retreating to older and/or more expensive artists is exactly what you would expect financially savvy collectors and dealers to do in such a brutal climate. And if that conclusion is accurate, then we should see a higher proportion of those older works at Art Basel Miami Beach next week—in both the works on view and the sales reported.