Art Fairs

The 6 Best Works at Frieze New York, From a $12,000 Mermaid Stuck in a Washing Machine to a Depiction of Black Gymnasts at Work

With no pretense towards any overarching theme, we present the best works on show at the fair.

With no pretense towards any overarching theme, we present the best works on show at the fair.

Pac Pobric

![]()

The biggest theme at Frieze New York this year—aside from the pleasure of art in traditional media—isn’t so dissimilar from what it was last year, or the year prior, or what it is at any art fair: sales. Collectors are looking for gems, dealers are hoping to close, and casual visitors are dropping eaves to catch up on the latest price for a work by Yayoi Kusama. Yes, there is plenty of programming without an explicit commercial focus (including a VR art installation, a jewel-box outsider art presentation, and Frieze’s perennial talks program), but at the bottom line, there’s a dollar sign, because we all have to eat.

So with no pretense towards any other binding theme beyond commerce, we present to you six of the best works on view at the fair, what they cost, and why they’re worth seeking out.

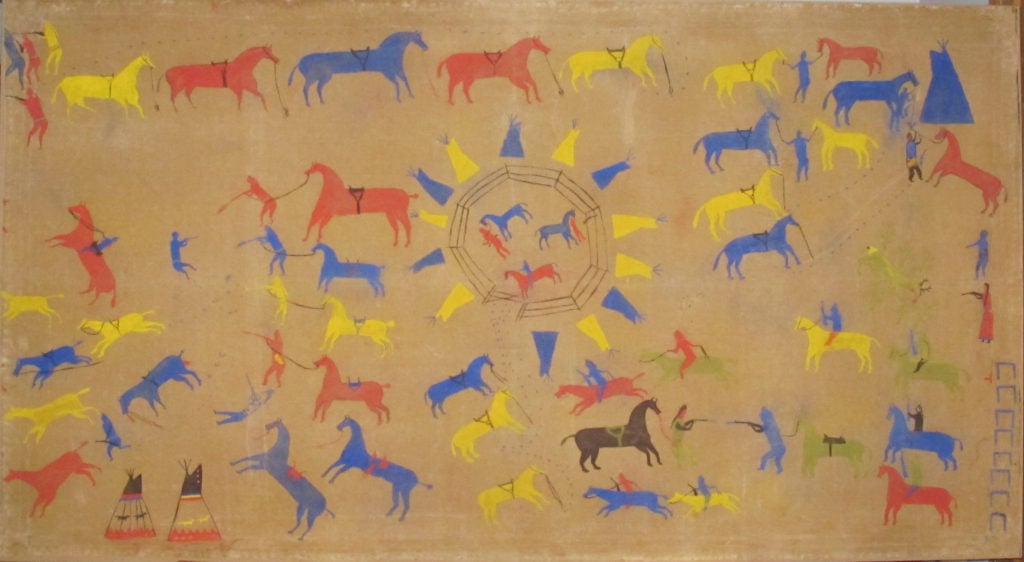

Big Spring, War Record (around 1915). Courtesy Donald Ellis Gallery.

This work—one of the only non-contemporary items at the fair—was commissioned by the Great Northern Railway for one of three hotels the company built in Glacier National Park, Montana. The picture was painted around 1915 by Big Spring, a Blackfoot Plains Indian, as a “war record” of his many feats. In the center, he depicts himself and two figures, including a sibling, raiding a Cheyenne horse corral, a battle in which his brother, shown lying on the ground with a rifle at his side, was killed. There were other attacks, too: on the far right, towards the bottom, are eight markings that signal Big Spring’s successful invasions, including one against a rival chief, denoted by a small red pipe.

“Oceanic and African tribal art, unlike Native American art, were largely canonized by Modernism,” says Aniko Erdosi, a director at the gallery. “If you collect Modern or contemporary art, you probably have an Oceanic or African piece. But that hasn’t been the case for Native American art, despite the fact that it was so influential for artists like Barnett Newman and Jackson Pollock. And that’s not even to mention that this is the first American art.”

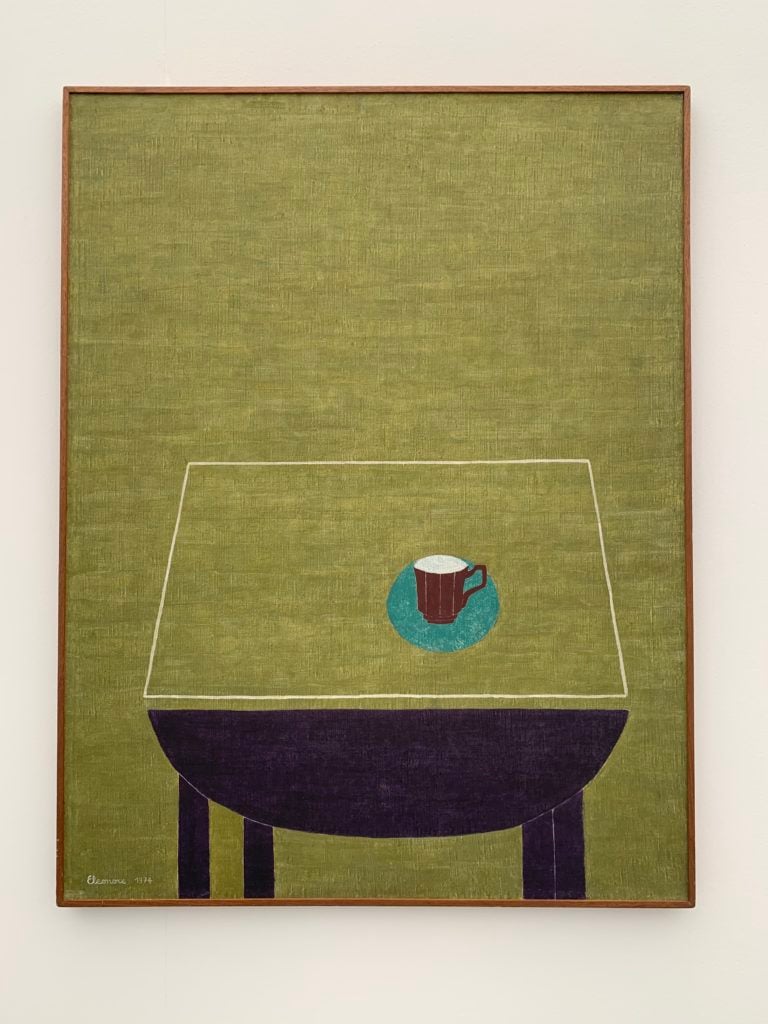

Eleonore Koch, Untitled (1974) at the Almeida e Dale booth at Frieze New York. Photo: Pac Pobric.

Eleonore Koch was born in Berlin in 1926, the daughter of a Jewish psychoanalyst and a lawyer. In 1936, three years after Hitler took over the chancellorship of the country, her family fled to Brazil, where she later took up studies in bookbinding. In the early 1950s, she met the Brazilian Modernist painter Alfredo Volpi, who taught her how to paint in tempera, a method used throughout history, but perhaps most famously by Renaissance artists such as Michelangelo. Among her best-known contemporary collectors is Brazilian education entrepreneur Orandi Momesso, who was also a close friend. Last week, he donated several works by the artist, who died in 2018, to the Pinacoteca do Estado in São Paulo.

“Koch looked at landscapes, but she didn’t really paint them as they were,” says Nathalia Zemel of Almeida e Dale gallery. “She painted them as she saw them, from her mind. And she was one of very few painters of her generation who did still-lifes.”

The gallery brought around 15 works by the artist to the fair. This untiled tempera painting is listed at $120,000, with others starting at $50,000.

Matthew Ronay, Control column, Wilts, Dyad (2019). Images courtesy the artist and Casey Kaplan, New York. Photo: Matthew Ronay.

Casey Kaplan’s delightful booth of 10 new works by the American sculptor Matthew Ronay is impossible to miss. Each of these peculiar little dyed basswood sculptures sits on its own, specially designed pedestal, and the entire arrangement was made specifically for the fair. Some objects—which bring to mind Jean Arp, Ken Price, or Ron Nagle—have a botanical resonance, while others look like curiously surreal visions of boots, fruits, or oddly colored internal organs. The most compelling ones make odd installation demands, like the sculpture above, which can only rest comfortably on its own custom plinth that comes with a cutout in the middle. “He really thinks about the architecture of the space he’s showing in, and the support systems for his works,” says Rosie Motley, an associate director at the gallery.

Casey Kaplan is currently presenting another show of Ronay at its 27th Street location (through June 15). Unlike the presentation on Randall’s Island, the Manhattan exhibition presents many of his works on a single long, low pedestal.

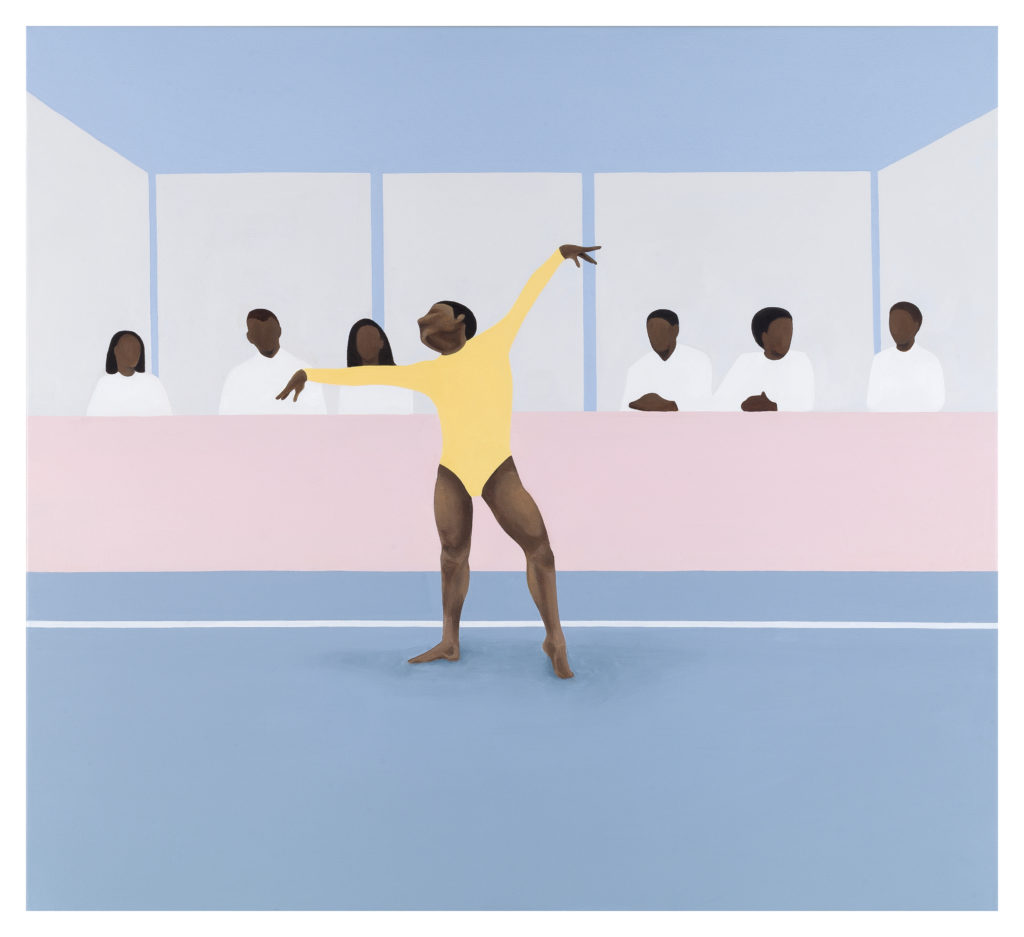

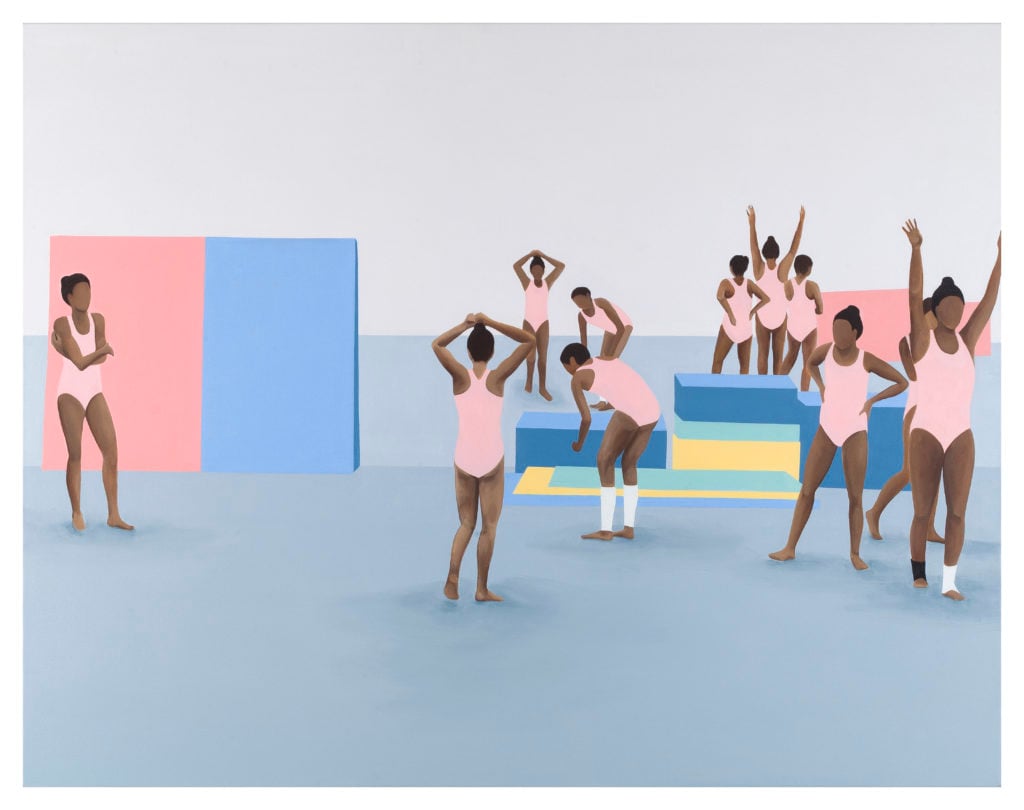

Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi, Practice (2019). Courtesy Mariane Ibrahim Gallery.

The New York-born, Johannesburg-based artist Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi is debuting new pictures at Frieze that depict black gymnasts at work. The clean, minimal paintings, full of figures with no discernible features, are focused on line, color, and visual clarity, and each emphasizes the gymnasts’ specific poses and movements. But the paintings are not without deeper commentary. “It’s partly about the black body in white space and under scrutiny,” says Mariane Ibrahim, the gallery’s founder, noting that two panels depict groups of judges, all of whom are also black. “It’s about who decides what’s in good taste, and it’s a metaphor for the high degree of exposure that reaching excellence demands.”

Importantly, Ibrahim says, the presentation will not be switched out throughout the fair’s run, even though several works have sold, including the above picture, which was bought by hip-hop entrepreneur Swizz Beatz for the Dean Collection. “The exhibition should be the same for everyone, from the first person to the last,” she says. “I think it’s democratic. It’s fair.”

The oil-on-canvas paintings are priced from $12,500 to $17,500.

Ewa Juszkiewicz, Untitled (after Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun) (2019). Courtesy lokal_30.

Since 2012, Polish painter Ewa Juszkiewicz has been working on a series in which she turns historical portraits inside-out. This work—adapted from a painting by Neoclassical artist Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun of the daughter of Louis XV’s chief valet—takes Le Brun’s staid, lifeless depiction and makes it delightfully perverse. “In the past, women were presented as beautiful but without character,” says Agnieszka Rayzacher, the gallery’s director. “They were neither beautiful nor ugly, and often they were just decorations for their powerful husbands, fathers, or brothers. Juszkiewicz gives them some character by uncovering something special.”

The artist has also worked on reinterpreting and recreating works that have been lost in wars or through other misfortunes. In 2015, she painted a picture after a small image she found of a work by Romantic artist Leopold Löffler that disappeared from a Polish museum around the time of World War II. While Juszkiewicz’s work was on show at lokal_30 in Warsaw, a woman recognized the image: it was the same as a painting her grandfather had stolen away from invading German forces and passed on to her. When it was returned to its institutional home soon after, a grand celebration was thrown, including a visit from the Polish minister of culture. “We never expected such a response!” Rayzacher says.

Olivia Erlanger, Pergusa (2019). Courtesy And Now Gallery.

Last but not least is Olivia Erlanger’s lovely, imaginative, and delightfully surreal installation of mermaid fins trapped in washing machines at And Now’s stand. The popular booth, which never seemed to be short on visitors, has three of her works, each with a differently colored tail.

The machines are rented from the Superior Laundry company out on Long Island, and the fins are made by a manufacturer in Florida. “There’s a whole mermaid subculture, and this guy can make these to whatever specifications you ask,” says James Cope of And Now gallery.