Every Monday morning, artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, looking deeper into a new record than a snobby DJ…

ROOM WITH AN (ONLINE) VIEW

On Friday, just ahead of Art Basel Hong Kong, Gagosian launched the latest iteration of its series of online viewing rooms. This time, the mega-gallery dedicated the entire virtual enterprise to a single painting: an untitled Albert Oehlen abstraction from 1988 listed at $6 million. And although the early conversation in the art media gravitated toward some of the special features of the new “room” itself, the result raises far more interesting questions about the state of the market.

About that result: On Saturday, Gagosian director Sam Orlofsky, who has been behind the online viewing rooms since their inception, told me that the painting had sold within three hours of going live. While he (and Gagosian Gallery as a whole) declined to confirm the final price, the gallery sent an email earlier on Saturday stating that it “exceed[ed] the current auction record for the artist.” For reference, that would be the roughly $4.7 million paid for Oehlen’s Stier mit loch (Bull with hole) at Christie’s London in October 2018.

Orlofsky identified the fast-acting buyer only as a private client known to the gallery who had previously “expressed interest in Oehlen only in the most basic sense.” The collector had never before acquired the artist’s work from Gagosian. Nevertheless, he or she bought the painting for a record price “sight unseen”—a fact Orlofsky knows because the work has been kept tightly under wraps for the past few years.

What does it all mean, though? Let’s unpack the bag Gagosian just secured.

Installation view of Albert Oehlen, Untitled (1988). © Albert Oehlen. Photo: Rob McKeever. Courtesy of Gagosian.

THE BACKGROUND

(FYI, if you already know how Gagosian’s online viewing rooms work, skip to the next section.)

For the uninitiated, Gagosian’s inaugural online viewing room went live during Art Basel last June. (I wrote about it in depth here.) It offered a limited number of works at prices that art-market orthodoxy would consider too high for remote buyers, with supplemental information reminiscent of auction catalogues and live assistance from sales associates just a click away. According to Orlofsky, the gallery largely conceived the format as a salve for the buyer burn-out created by oversaturated stretches of the art-market calendar. As he told me at the time, “If we can find a more efficient portal or tool for them to voyeuristically participate” during Art Basel (or other big IRL market events), “we might have a better chance of actually doing business.”

Yet Gagosian ratchets up the pressure on clients in its virtual back rooms in some of the same ways a traditional art fair does. Each one is accessible for just 10 days, and when the works on offer are gone, they’re gone. For Gagosian, then, the gambit is that the online viewing rooms deliver the best of both worlds: easy accessibility to a wide range of high-net-worth buyers, but without sacrificing the time-tested aphrodisiac of competition.

Results were robust even before the Oehlen adventure. The gallery says it placed five of the 10 works offered in the pilot online viewing room, ranging from a Jeff Elrod painting for $150,000 to, you guessed it, an Albert Oehlen abstraction for $1.1 million. A second edition of the online viewing room delivered even more sales when it went live during Frieze London last fall. And those past successes set the stage for the format’s latest iteration.

The ‘Historical Analysis’ page in Gagosian’s third online viewing room, devoted entirely to Albert Oehlen’s Untitled (1988). Courtesy of Gagosian.

ANALYZE THIS

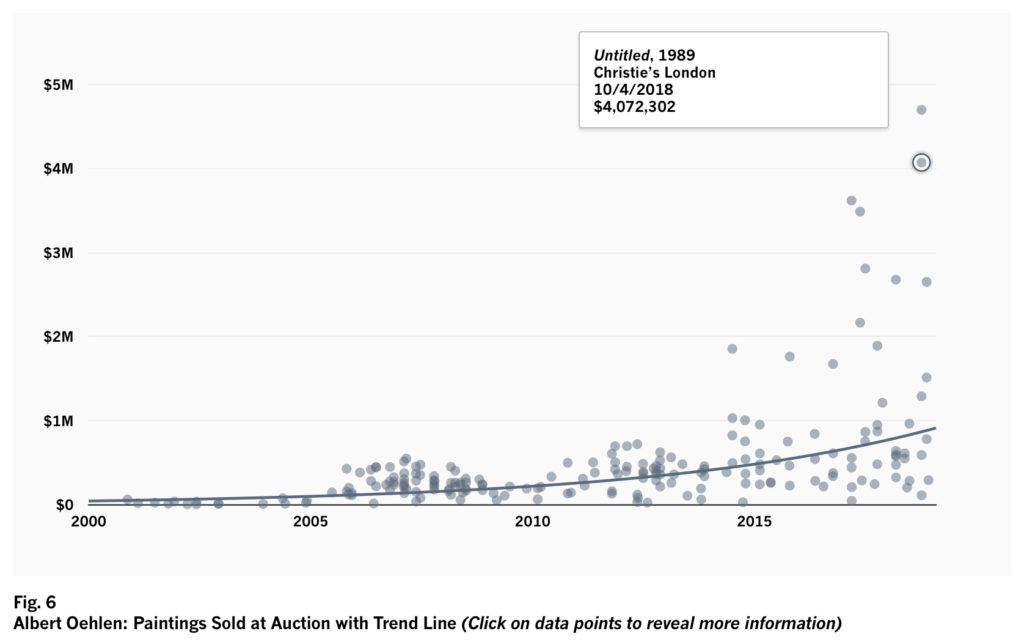

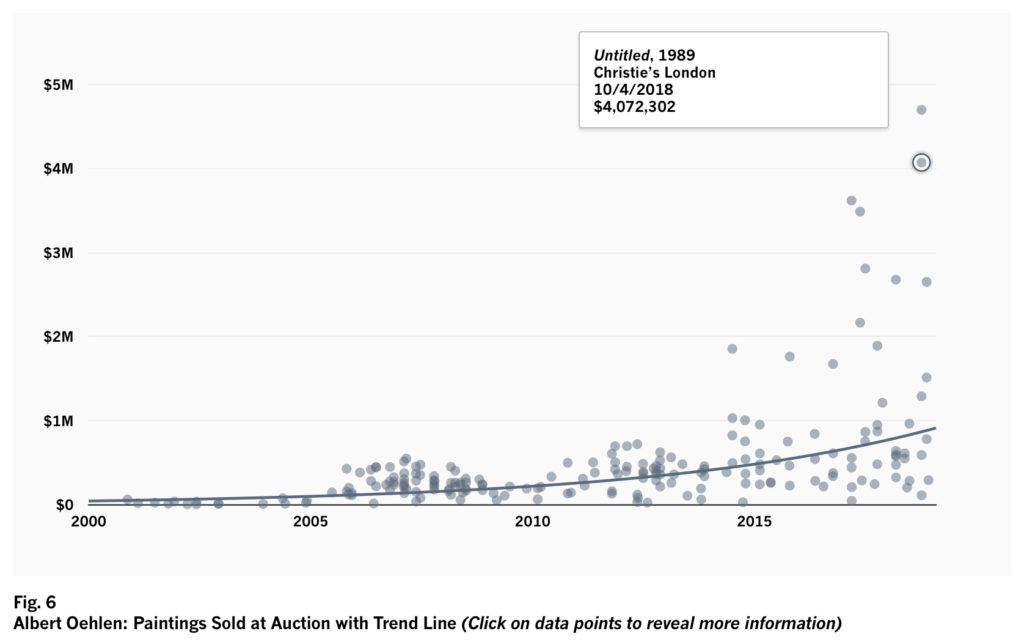

Apart from zeroing in on a single consignment, the Oehlen online viewing room offered a few other new developments. The most buzzed-about, thanks in part to an ARTnews preview piece last Tuesday, was a chart-based market analysis of the artist’s auction results (broadly similar to the types of data visualization pieces that we do at artnet). One example: a scatter plot of Oehlen’s auction sales since 2000, complete with a trend line whose upward swoop accelerates noticeably around 2014, when an Oehlen first broke the $1 million threshold.

I’d definitely say it’s notable for Gagosian to take this approach public. We should just be careful not to exaggerate its novelty as a whole, especially among the ecosystem’s apex predators.

When I asked Orlofsky whether data analysis is a tool that Gagosian’s sales team started using in pitches before the Oehlen viewing room, the most salient part of his answer was this: “I probably have five to 10 colleagues who do something even more sophisticated than what you saw there, but it’s not systemic.”

A market-analysis graph in Gagosian’s third online viewing room, devoted entirely to Albert Oehlen’s Untitled (1988). Courtesy of Gagosian.

In other words, there is no Gagosian Corporate Sales Academy where staff are told to pitch art by a set of strict processes. Different staffers use different techniques with different clients. Still, data analysis and visualization are two of the tools in the shed—and have been for some time.

In fact, if Gagosian’s most direct competitors (and galleries further down the food chain) haven’t also been selectively crunching numbers and plotting trend lines for several years, I’ll adopt the same look of permanent astonishment that you get from a cheap facelift. As evidence, when I worked at a gallery, I was putting together chart-packed “quarterly reports” and year-over-year summaries for aggressively finance-minded clients starting around 2007, and that was for a modestly sized operation with (extremely) limited organizational firepower.

The reality here is pretty simple. Once galleries and dealers start pitching clients on works priced in (or even near) the millions of dollars, they have to be prepared to discuss art as a financial asset, including by replicating the lowest-level trappings of an investment portfolio. Buyers don’t necessarily need to know that the work they’re considering will appreciate x percent in y years. But they generally want assurances that they’re not going to lose money on the transaction. It’s just basic fiscal responsibility.

Sometimes you can satisfy that demand by talking about an artist’s museum resume and naming other prominent private clients who collect their work. Sometimes you can do it by rattling off auction history. And sometimes you have to go all the way to Excel charts. But selling art in 2019 is a service business. Each client has their own transactional needs, and you’d better be able to satisfy all of them if you want to compete at the highest level.

Bidding for David Hockney, Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures) (1972) at Christie’s post-war and contemporary evening sale in November 2018. Courtesy of Christie’s Images Ltd.

RECORD SETTING VS. RECORD COLLECTING

This discussion leads us back to the record-setting element of the Oehlen viewing room.

Now, since Gagosian has refused to confirm the final sales price, I can’t blame skeptics who question whether the mega-gallery really surpassed Oehlen’s nearly $4.7 million auction high. But is Gagosian less trustworthy here than the big auction houses, whose records depend on well-documented shenanigans like making direct financial guarantees to consignors, brokering irrevocable bids by third parties, and sanctioning entities with an ownership stake in offered works to drive up the price in the room?

For years now, “auction” records have just been private-resale records with public packaging. All that matters is whether a seller can secure two things: a buyer at a lofty-enough price to warrant headlines, and the consent of the parties involved to broadcast the bare-minimum terms of the deal. The timing and the route to that destination are irrelevant. To me, that makes Gagosian’s Oehlen record as reliable and legitimate as any mark set by Christie’s, Sotheby’s, or Phillips “at auction,” even if, contrary to Orlofsky’s word, the gallery hatched the deal before the online viewing room actually went live.

What’s the value proposition for Gagosian in the Oehlen sale, then? On one hand, it’s a way to siphon profitable business away from the auction houses. Consignors inevitably follow the market leader. Before this weekend, anyone with a major Oehlen painting to sell would have been most likely to offer it to Christie’s straightaway, since that house set the artist’s auction record.

Now, though, any potential Oehlen consignors will be inclined to look at Gagosian first. The same is likely true of any superstar artists ready to have frank discussions about their own markets if their prices hover in the same range as this record-setting Oehlen.

Still, this is more of a surgical strike by Gagosian than an artillery blast. Orlofsky put it this way: “There is only a small handful of artists where we could be the ones to out-duel the auction houses,” which, in general, are “15 steps ahead in trying to set the next record.” Oehlen, however, presented a rare opportunity where the gallery could make history between $5 million and $10 million—before his market, as Orlofsky says in a video inside the online viewing room, “breaks through into the stratosphere.”

Albert Oehlen (2008). Photo by Oliver Schultz-Berndt. Courtesy of Gagosian.

The other value proposition lies in the online viewing room itself. Orlofsky says that the gallery plans to be “more ambitious” with each new iteration of the format, most likely by gunning for higher gross dollar values than in previous editions, as well as experimenting with other enticements that might appeal to consignors and artists. After establishing what he called the “very juicy precedent” of the Oehlen record, Orlofsky made a comparison: Perhaps making a consignor’s lone work the focus of an online viewing room is not so different from an auction house offering to make a consignor’s lone work the cover lot for a prestigious evening sale catalogue. The success here strengthens the pitch for any other novelties Gagosian can cook up.

To that end, the data that matters most for the future isn’t the historical kind that Gagosian sourced from auction results and packaged into succinct charts on Oehlen. It’s the new data on collectors that Gagosian is vacuuming up in each new viewing room—a resource that incentivizes the gallery to iterate frequently. “We just want to have done this enough to start to notice patterns or trends or opportunities,” Orlofsky says.

For instance, a gallery spokesperson confirmed that Gagosian made contact with 537 new collectors via the original online viewing room. How many more people have they “met” in the ones since? What else have they learned about them that could be valuable? Whatever the answers, these data-based insights will be the “next set of stimuli” guiding Gagosian’s innovations to come, according to Orlofsky.

Crucially, though, these insights only manifest at volume. Which means private-market analytics are just another realm where the mega-galleries and auction houses occupy a class by themselves. In that sense, Gagosian’s record-setting Oehlen experiment means less for the average gallery than it does for Sotheby’s, Christie’s, and Phillips—except as confirmation that, in data as in dollars, the rich continue to get richer in this business.

That’s all for this week. ‘Til next time, remember: Records were made to be broken, but not by everybody.