Galleries

Art Law on Consumer Protections for Purchasers of Prints and Multiples

When it comes buying art, there really is safety in numbers.

When it comes buying art, there really is safety in numbers.

Judith Wallace

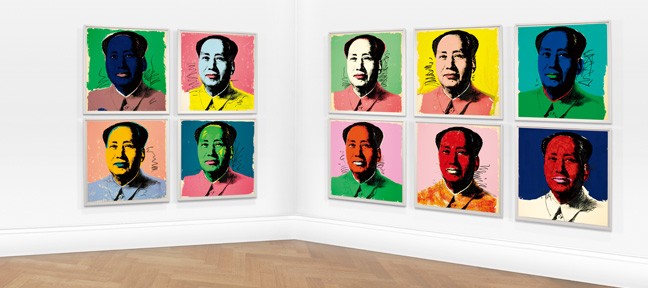

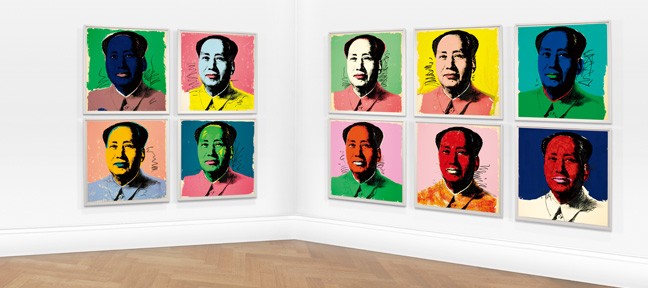

This essay addresses issues presented in buying and selling art created in multiples (as opposed to unique pieces)—prints, photographs, and editioned sculpture. New York and a few other states have legislation that targets art in multiples. It would be wise for dealers and buyers to be aware of these rules.

● ● ●

An important aspect of New York’s law governing art transactions is that purchasers of prints, photographs, and editioned sculpture (multiples) have more extensive consumer protections than purchasers of (unique) multi-million dollar paintings whose sales make headlines, and, moreover, can seek attorneys’ fees and other costs for warranty claims.

New York Arts and Cultural Affairs Law Includes Protections for Multiples

New York’s Arts and Cultural Affairs Law is, in part, a consumer protection statute. Chief among its protections is the “express warranty” provision stating that when an art merchant (i.e., dealer or auction house) provides a certificate of authenticity to a non-merchant (i.e., collector) buyer, it creates an express warranty by the merchant for the facts stated in the certificate (such as the identity of the artist who created the work).1

But for art “multiples,” New York law also adds further warranties and disclosure requirements. Multiples are defined as works “produced in more than one copy.” New York created requirements for print and photographic multiples in 1981, and in 1990 added sculpture.2 Only about 10 other states have statutes applying to prints and photographs, and only California and Iowa also include sculptures.3

Significance of Choice of State Law

Thus, it is important to agree what law governs the sale. Without an explicit statement (as in an invoice), this can be an issue if there is a refund demand. Dealers who are purchasing for resale in New York should be sure they have recourse against their predecessors, especially if they are purchasing art in a transaction that might be governed by another state’s law. For example, an out-of-New York state dealer who bought on an “as is” basis, and sold through a New York auction house to a collector, was left exposed to a New York warranty claim for the total purchase price.

Required Disclosures

The New York “multiples” law requires dealers to disclose information about the size of the edition and how, when, and by whom the master and multiples were created. These disclosure requirements vary by type of work and date of creation, with much less required for works created before 1949. The seller warrants the accuracy of these statements.

Thus, for example, if there is a significant difference in value between a lifetime and posthumous cast (as is sometimes the case), the buyer should be sure there is a specific written representation of lifetime creation. The same holds true for edition size and the number of editions. There is a misconception that there is a legal limit of 12 sculptures in an edition, which is probably due to confusion with American import regulations, which treat the first 12 works in an edition of up to 50 sculptures as “original” works exempt from duty (if there are more than 50, none are exempt). In one case, years after a sale, the purchaser was astounded to discover that the dealer had failed to tell her there were two editions with a total of more than 100 casts of the bronze sculpture she had purchased for a six-figure purchase price.

Ability to Recover Attorneys’ Fees

The multiple buyer’s strongest protection for warranty claims is that the buyer can seek attorneys’ fees, expert witness fees, and 9% interest, and—if the seller knowingly provided false information—up to triple that amount in damages.4 Quite obviously, this provides an incentive for buyers to seek to enforce their rights and an incentive for sellers to settle claims.

Dealers Are Better Off When They Purchase, Worse Off When They Sell

The multiples warranty also applies to dealers as well as non-dealers,5 and to all seller representations. Dealers are also liable on consignments. The multiples law explicitly states that art merchants who sell consigned works are liable for the warranty6—whether or not the dealer can recover from the consignors. This is different from the usual rule that agents are themselves liable only if they do not disclose the names of their consignors, and provides additional incentive for dealers to ensure that the information they have from their consignor is reliable.

Different Warranty Standard for Multiples

The warranty standard also differs for multiples. For the generally applicable “express warranty” of the Arts and Cultural Affairs Law (for unique pieces), courts have held that if a seller had a “reasonable basis in fact” for its representations at the time of the sale, it has not breached its warranty.7 As a result, under this standard, if a dealer does the appropriate due diligence and, for example, the attribution of the artwork is supported by the leading expert or a consensus of scholars, the dealer would not be liable for breach of warranty even if the work can (well after the sale) be shown to be a forgery. But what if the dealer relied on a 10-year-old opinion from the leading expert, knowing that she had been researching a catalogue raisonné in the interim? Consider that the process of systematically collecting information can reveal facts that cause the expert to reexamine previous assumptions and subject the works (or even the artist’s entire oeuvre) to heightened scrutiny.

In contrast, the “multiples” provisions expressly state that a dealer’s “reasonable basis in fact” is not a defense to a warranty claim.8 Thus, a warranty claim brought under the multiples provisions of the Arts and Cultural Affairs law is whether the artwork is or is not as it was warranted, based on the experts testifying at the time of the trial. This means that a multiple buyer could assert a warranty claim based on post-sale scientific testing (even if it would not have been customary for a seller to perform such testing), new information about the history of the work, or a change in scholarly opinion. This can seem harsh, especially if the testing uses a new technology that would not have been available to the seller at the sale date.

Recurring Issues in Multiple Warranty Disputes

However, it can be challenging to prove that a multiple is not authentic. This is especially true for early 20th-century bronze sculptures, which were sometimes produced in unnumbered editions, on an “as needed” basis. For example, there are cases in which a dealer (for example, the Parisian dealer Ambroise Vollard in the 1920s and 1930s) had a single cast in his gallery, and was authorized by the artist to order the fabrication of additional (unnumbered) casts when an interested buyer turned up. Because these might be produced by different foundries over a period of decades, each foundry using proprietary bronze alloys of varying composition, with different patinas, by foundry workers using different casting and finishing techniques, casts could vary considerably, making comparison to casts with verified provenance inconclusive.

In addition, sculptures do not necessarily bear any indication of the artist’s approval after fabrication is complete. Prints and photographs are signed and numbered by the artist after they are fabricated, but an artist’s signature cast in a sculpture is no proof of the artist’s authorization for the number of casts in the edition, the artist’s approval of the quality of the completed work, or fabrication during the artist’s lifetime. An “authorized” bronze might have no greater connection to the hand of the artist than an extra cast created by a foundry, and it can be quite challenging to prove whether a cast was authorized by a long-dead artist, if gallery and foundry records are missing. Thus some artists’ estates were apoplectic in 1988 when a New York foundry owner auctioned off hundreds of the plaster models used in bronze casting, since those plasters could be used to create unauthorized bronzes that would be indistinguishable from authorized ones. Alternatively, in some cases, posthumous casts are less problematic, as when an artist began a planned edition, but ran out of funds, and the estate completed the edition after the artist’s death.

Another recurring issue that is addressed by the Arts and Cultural Affairs Law only for sculptures, but not for multiples on paper, is the number of editions that will be created in the future. A buyer may offer a certain price for a work that is one of an edition of 10, and can be harmed when the artist produces later editions of the same work with slight variations in material, color, or dimensions, diluting the market value of the first edition.

Conclusion

Warranty disputes over multiples often raise art-historical questions about authenticity, what it requires by way of involvement by the artist, and why it should matter if a particular multiple was approved by the artist if there is no meaningful physical distinction in the work itself. (Indeed, an unauthorized cast might even be of superior quality.) However, these facts about creation and the edition as a whole are usually relevant to a collector’s decision about whether to purchase, and what price to pay. Therefore, the Arts and Cultural Affairs Law recognizes the buyer’s right to have these facts disclosed, and to obtain a refund if the multiple is not what it was represented to be.

New York, New York

June 2015

Judith Wallace

Carter Ledyard & Milburn LLP

Notes

1 NYACAL § 13.01.

2 NYACAL § 11.01 (20)

3 See, e.g., Cal. Civ. Code §§ 1740 and Iowa Code Ann. § 715B.

4 NYACAL §§ 15.13(4), 15.15.

5 NYACAL §§ 13.05, 14.06, 15.11.

6 NYACAL § 15.15.

7 Dawson v. G. Malina, Inc., 463 F. Supp. 461, 467 (S.D.N.Y. 1978).

8 NYACAL § 13.05.

Editor’s Note

This is Volume 5, Issue No. 3 of Spencer’s Art Law Journal. This spring/summer issue contains three essays, which will become available on artnet in August 2015.

The first essay discusses the process by which Old Master paintings are authenticated in the context of a claim that an autographed Caravaggio replica had been overlooked by a major auction house.

The second essay examines dealer exposure and buyer legal protections for works of art in multiples.

The third essay focuses on a recent court decision valuing fractional interests in art, which may help keep your collection in the family.

Three times a year, this journal addresses legal issues of practical significance for institutions, collectors, scholars, dealers, and the general art-minded public.

— RDS