When Charles White died in 1979 at age 61, he was reasonably famous. His work was in 49 museums, he had won 39 awards, and he had been the subject of 48 books and 53 one-man shows. The artist Benny Andrews said in his obituary that even “people who didn’t know his name knew and recognized his work.”

Today, however, White is hardly a household name. His first retrospective in 30 years has just opened at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. His path from humble beginnings to renown to cult figure—and, finally, back to renown again—is at once singular and representative. As a teacher and prominent artist, White had a unique impact on some of today’s most prominent creators and, more recently, has been brought back into focus because of his students’ own fame. But his path is also representative of the trajectories of many prominent artists of color, who were recognized in their lifetimes only to be willfully ignored or revised as a footnote to history after their deaths.

Now, a new traveling retrospective seeks to recognize White’s contributions to American art—and the market is following closely behind.

Humble Beginnings

Born in Chicago in 1918, White began to draw as a child during the stretches he spent at the main branch of Chicago’s public library, where his mother would drop him off while she went to work. He won a scholarship to the Art Institute of Chicago at 16 and later enrolled at the school full time—but only after two other art schools accepted him, then turned him down upon learning he was black.

During his time in Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles—the three cities where the current major retrospective is stopping in that same order—White inspired and influenced countless younger artists as both role model and teacher.

Auction prices for his work are less than one might expect for an artist of his stature and influence: they top out around $500,000. This can likely be chalked up to a mix of several factors: the fickle nature and systemic racism of the art market; the collecting community’s love/hate relationship with figurative work; and the fact that the bulk of material by White that comes to market are works on paper, which tend to fetch lower prices than paintings. (White embraced the medium amid struggles with tuberculosis, which made painting more challenging for him.)

Of the more than 220 works listed in the artnet Price database, all but ten auction results are under $100,000. Over the past decade, White’s work has generated a mere $3 million at auction.

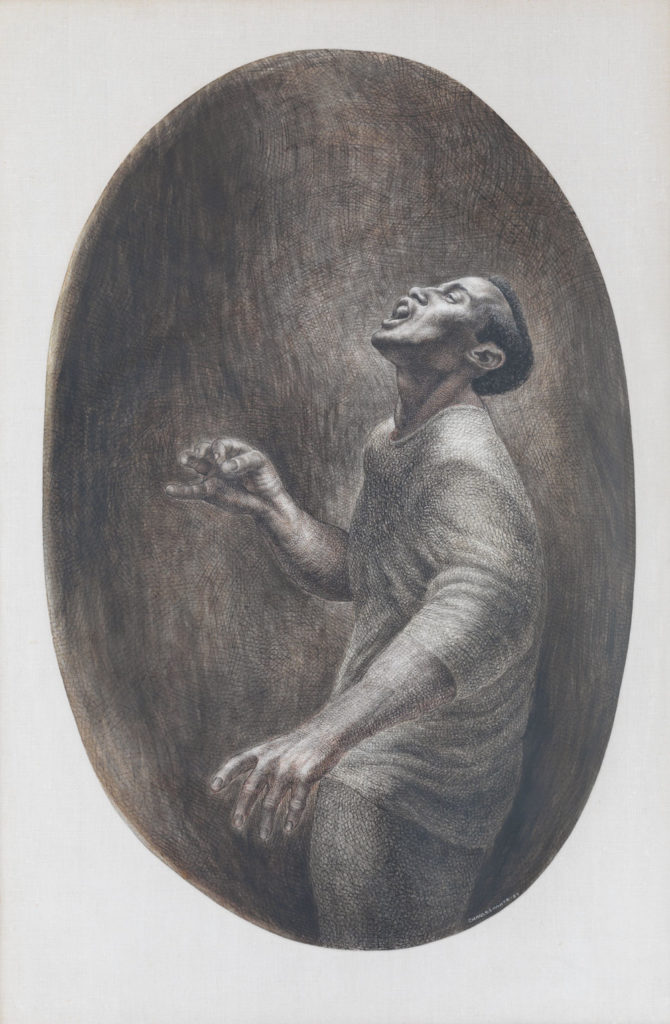

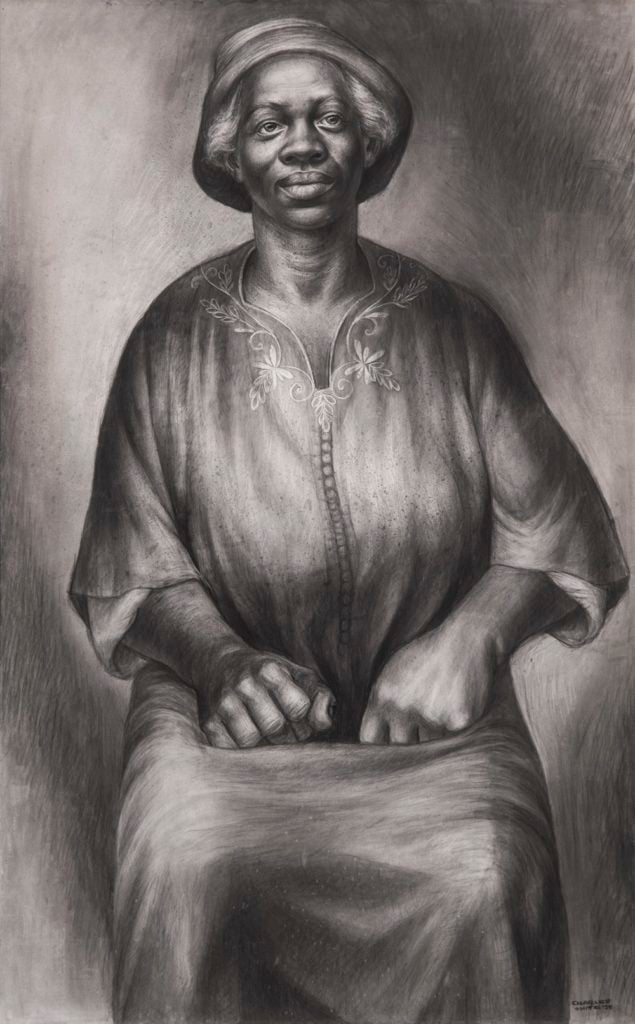

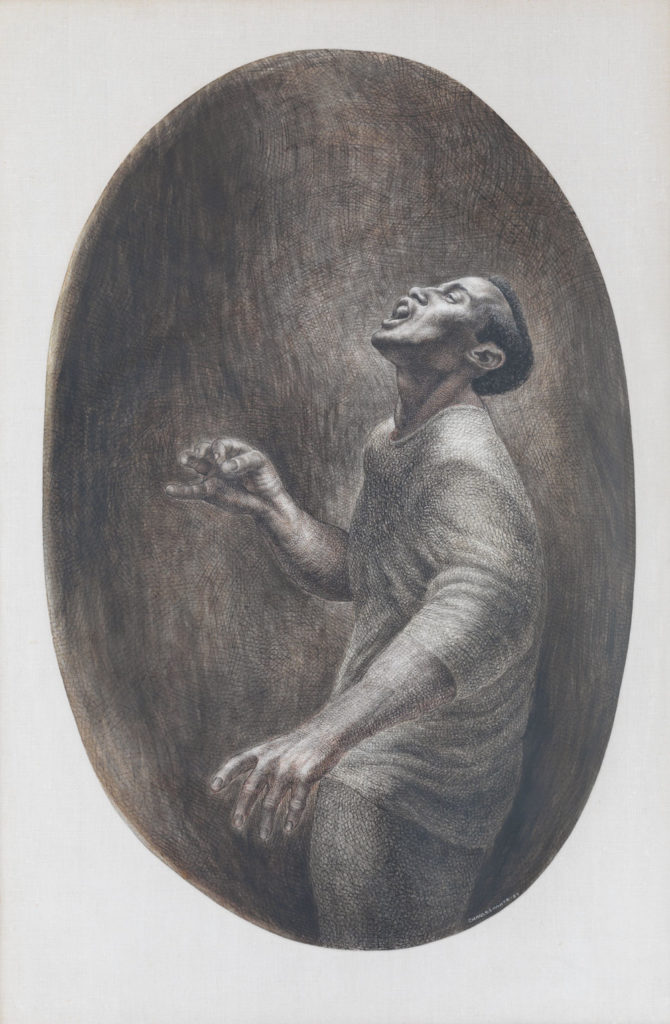

Charles White, Nobody Knows My Name #1 (1965). Courtesy Swann Auction Galleries.

But prices have been noticeably picking up amid the recent attention. His auction sales in the first half of 2018 were more seven times his total for the full year of 2015.

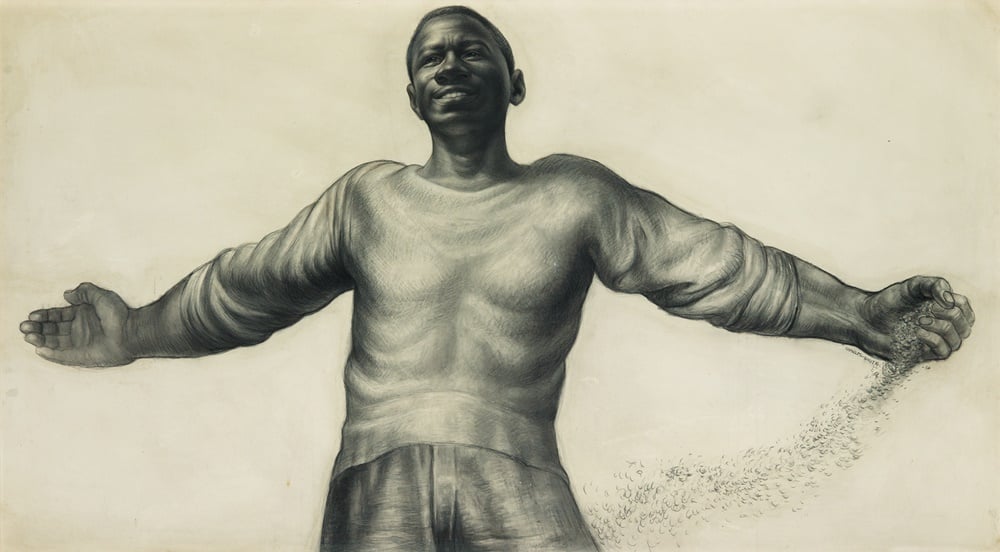

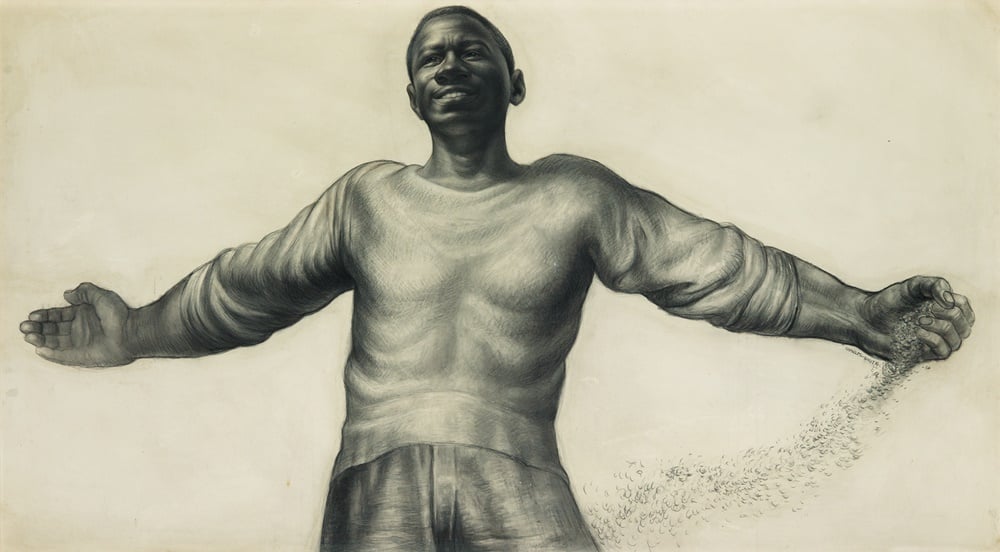

Swann Auction Galleries in New York, which has handled the bulk of White’s auction sales to date, set a new record for the artist this spring with O Freedom, (1965), a charcoal drawing showing a smiling African American young man with his arms outstretched, for $509,000.

Another high mark for White came last week, when Swann sold the charcoal drawing Nobody Knows My Name #1 (1965), a haunting, dark composition with a figure floating and looking at out the viewer, for $485,000—the second highest auction price for the artist. The buyer was New York dealer Michael Rosenfeld, whose current show, “Truth & Beauty: Charles White and his Circle,” presents White’s work alongside that of friends and students including Roy DeCarava, David Hammons, Betye Saar, and Hale Woodruff.

On the private market, too, “there has definitely been a rise… in anticipation of the retrospective,” Rosenfeld says. He had anticipated even more competition for the charcoal work based on presale interest, including calls from his own clients, he adds.

Kayla Carlsen, vice president and head of the American art department at Sotheby’s, says the auction house is working with a number of institutions that are “starting to sit up and take notice and make up for lost time” when it comes to acquiring important work by White and his peers. “People are actively looking for them, where they had just not been paying attention before,” she says.

But contrary to some of the speculative market activity that crops up around sudden art stars, White’s market spike is more “organic,” Swann specialist Nigel Freeman says, noting that the attention has come with a rise of institutional acclaim. “The retrospective is showing the depth and breadth of his work,” he notes. “I think his stature is only going to increase, both nationally and internationally.”

Charles White, O Freedom (1956). Courtesy Swann Galleries

The State of the Market

Many factors have contributed to the slow burn of White’s market.

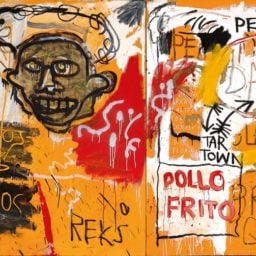

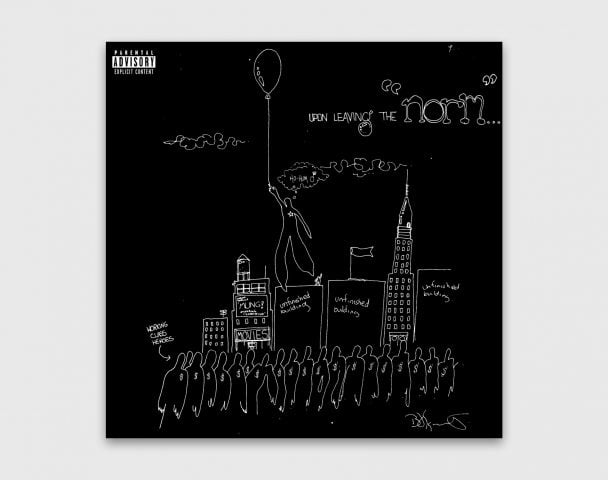

White had a relatively active primary market during his lifetime—he had a series of solo shows with New York’s ACA Galleries and often produced graphic art for record covers or calendars and books—which meant that much of his work was snapped up around the time it was made and has not re-emerged. It also means there is no one dominant holder of his work—though institutions like MoMA and the Art Institute of Chicago have made concerted efforts to acquire major pieces in recent years.

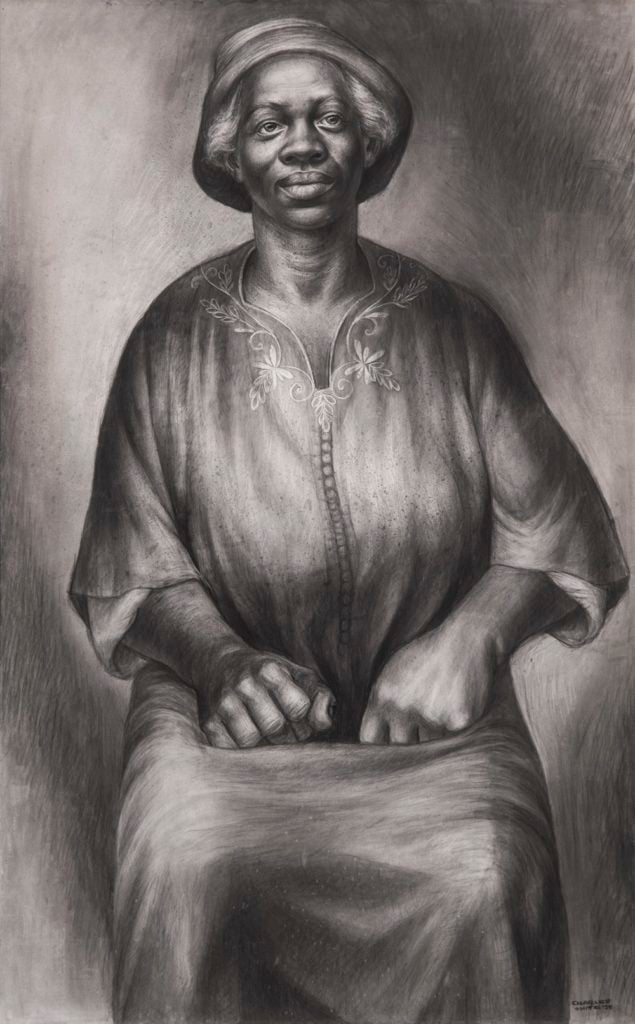

Charles White, Untitled (circa 1942) © Charles White Archives; Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY

Esther Adler, the MoMA curator who worked on the current retrospective, estimates that roughly two-thirds of the works in the show, including its own holdings, are from institutions, while roughly one-third are from private collectors. Some acquired works over the past decade and others have been on the owners’ walls “since Charles White made them.”

His market has been both more restrained and more volatile than those of some of his peers. “There have definitely been ups and downs in his market over the past 30 years,” Rosenfeld says. “There was a growing interest 30 to 20 years ago, a flattening of interest from about 20 to 15 years ago, and it might be safe to say, a decline from 15 to five years ago.”

In the early 2000s, Swann notes that the auction record for White was around $38,000; by 2007, that high water mark had jumped to $300,000 for an important figurative work. That record was not broken until 2011, and the 2011 record stayed in place until this year.

Experts attribute some of this fluctuation to shifting fashions. Around 20 years ago, collectors and museums began to “put their resources into contemporary art and abstraction,” Rosenfeld says. “They were pulling away from buying historic works of the 20th century. So you might say Charles White got put on the sidelines for a while.”

A parallel situation occurred in the museum world, as the legacy of minimalism and Abstract Expressionism led to a focus on “removing the hand of the artist,” Adler says, while “Charles White was essentially going in the exact opposite direction at the same moment. And I think people aren’t necessarily used to seeing that history in conversation with the other histories.”

Charles White, I Been Rebuked & I Been Scorned (Solid as a Rock) (1954)

© Charles White Archives; Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY

A Ringing Endorsement

Now, in an unexpected twist, the current broader fervor for works by contemporary African American artists has helped refocus the lens on an older generation of artists like White.

“No other artist has inspired my own devotion to a career in image making more than he did,” Kerry James Marshall wrote of his former teacher in an essay titled “A Black Artist Named White” for the retrospective’s catalogue. “I saw in his example the way to greatness.” Marshall (who is now the most expensive living African American artist at auction) first encountered White during an eighth grade visit to LA’s Otis College of Art and Design, where White was teaching. Then and there, Marshall says, he resolved to go to Otis on the spot, despite not even having entered high school yet.

Artists like Marshall’s desire to clarify and cast light on their influences has not gone unnoticed by collectors. “We’ve had collectors who have not acquired 20th century art before coming into the gallery,” Rosenfeld says. Marshall and David Hammons, another of White’s students, “are great contemporary artists who are revered and respected. I believe that has given confidence to buyers of their art—who are some of the most significant collectors in the world—to take a very close look at the work of Charles White.”

While some longtime White collectors and enthusiasts have been grumbling about the rise in his prices, contemporary art collectors who are accustomed to shelling out seven- and eight-figure prices for major work, don’t bat an eye at six-figure asking prices and even find them “reasonable,” says Rosenfeld.

And it’s a good thing, because they are likely to keep trending higher. Rosenfeld says prices for drawings now run between $500,000 and $1 million. Meanwhile, some of White’s masterworks, like Black Pope (Sandwich Board Man) (1973)—the centerpiece of the retrospective, which depicts a luminous street-corner preacher—could fetch well in excess of $1 million if it were to come up for sale.

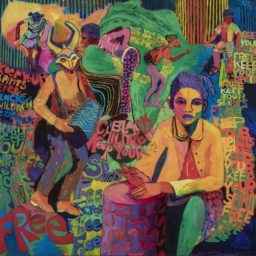

Charles White, Folksinger (1957) Collection Pamela and Harry Belafonte © 1957 The Charles White Archives. Photo Credit: Christopher Burke Studios

While White’s work from the ’60s and ’70s has proven the most desirable for collectors, the retrospective also includes other major paintings and works made during White’s time as an artist with the Works Progress Administration. Along with a major WPA mural loaned by Howard University, for which MoMA has created a special frame, there are tempera paintings, photographs, ephemera, and works on loan from White’s good friend and patron Harry Belafonte. (MoMA is taking a particular focus on White’s New York years, while the Art Institute paid more attention to White’s Chicago years and LACMA intends to zero in on his time on the West Coast.)

Adler says White’s work first really came on her radar after curator Kellie Jones included it in “Now Dig This! Art and Black Los Angeles 1960-80” as part of the Getty-funded, California-wide Pacific Standard Time initiative. While MoMA was motivated to acquire a number of White works around that time, Adler says, “we became aware of the dearth of scholarship and the need for a new, contemporary overview. Of course Chicago happened to be thinking the same thing at the same moment, so it was a meeting of the minds.”

Adler says for her and the other institutions involved in the retrospective, the chance to mine the depths of White’s oeuvre and to recontextualize the work for a contemporary audience has been particularly rewarding.

“It’s very rare for a curator at a major institution to get to do so much work on an artist,” says Adler. “Often it’s been done before, and you’re searching for new ways to bring new ideas and new light to the work. But Charles White was so overdue for this retrospective. There was so much for us to discuss and do. It has really been a gift.”