Reviews

At the Broad Museum, the Groundbreaking ‘Soul of a Nation’ Puts a Refreshed Focus on the Struggles of Black Artists in LA

The importance of art collectives—and collective struggle—stands out here.

The importance of art collectives—and collective struggle—stands out here.

Colony Little

The 1960s ignited a generation of activists fueled by inequity, unrest, and uprisings, and the art created during this time was a visual by-product of the nation’s struggle toward equality. But the work of African American artists during this era remained in the shadows of the art world, largely unrecognized by mainstream audiences.

In other words, the sustained inclusion of Black art in the historical canon is a slow, evolutionary process that was catalyzed by revolutionary acts.

This radical cultural energy is the focus in “Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power 1963-1983,” which has just arrived at the Broad in Los Angeles. The show examines the work of 60 artists and explores the historical and cultural influences that define their unique approaches to Black art both as a vehicle for change and an expression of self-exploration.

Installation view of “Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power 1963-1983” at the Broad, 2019. Photo by Pablo Enriquez, courtesy the Broad.

Since its debut at the Tate Modern, and throughout its subsequent appearances at the Crystal Bridges Museum in Arkansas and the Brooklyn Museum in New York, the show has been the subject of much praise. One specific thing the L.A. incarnation reinforces is the essential function of a sense of collectivity to counteract Black artists’ invisibility and exclusion from the mainstream art world.

This is not a show about defining or explaining Black art, abstractly. The artists here responded to shifting cultural tides in dramatically divergent ways. Rather it shines a critical light on the vital work created by marginalized artists—and, importantly, the networks that sustained them. Collectives became important access points into powerful networks of cultural activists and allies that included politicians, collectors, entertainers, and scholars who aligned to fight for racial equality and justice.

Romare Bearden, The Conjur Woman (1964). Photo by Colony Little, courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York.

“Soul of a Nation” guides viewers through a variety of work created by regional collectives from across the country. These include New York’s Spiral, whose 1964 show titled “Works in Black in White” featured thematic and stylistically divergent works from Romare Bearden, Jacob Lawrence, and Emma Amos that wryly reflected the futility of defining Black art through binary parameters.

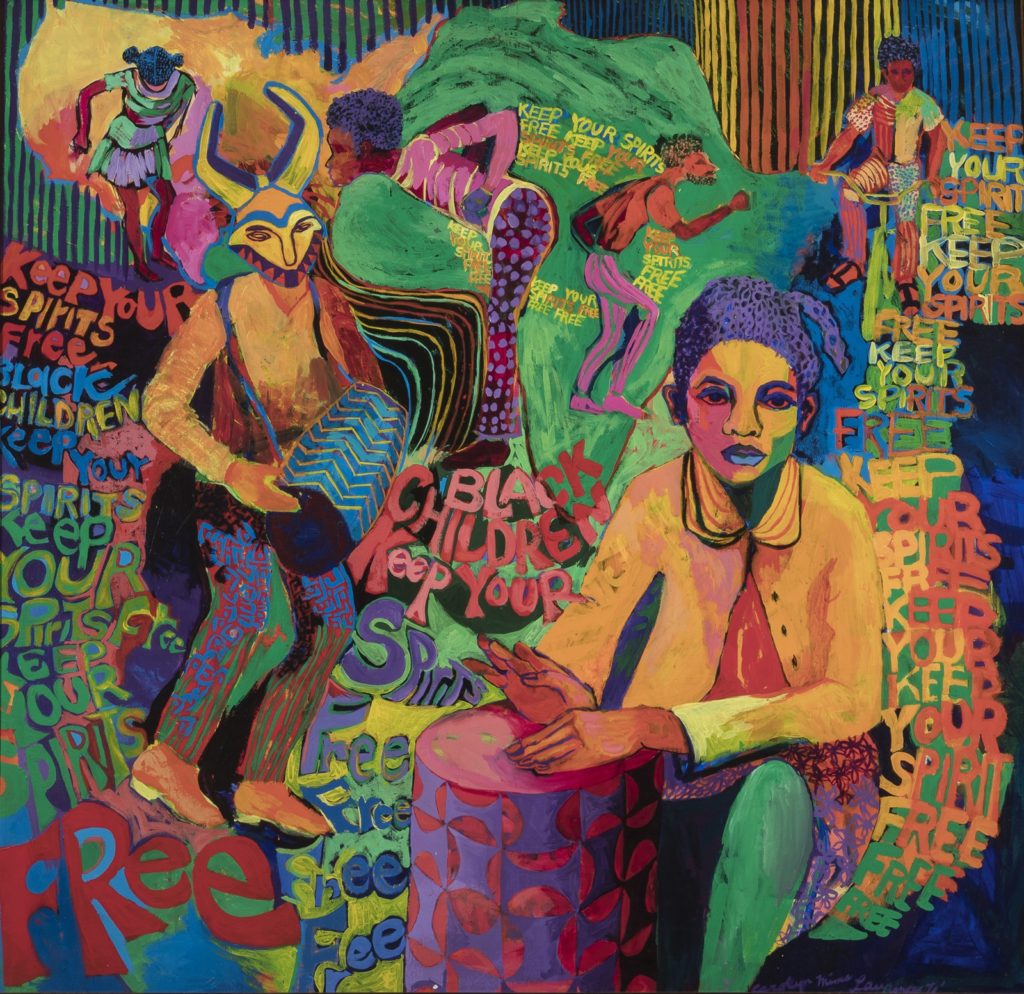

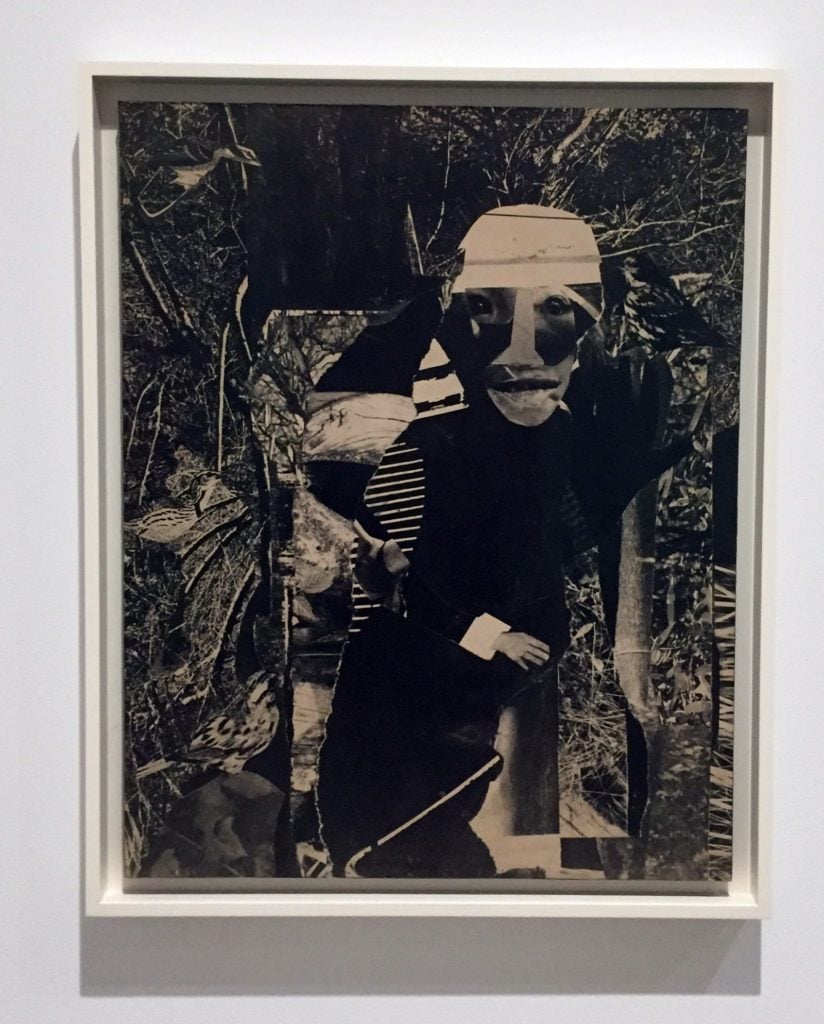

Roy DeCarava, Bill and Son, New York (1962). Photo courtesy Colony Little

Emotionally evocative photography by members of the Kamoinge Workshop is thoughtfully represented. Also based in New York, Kamoinge was a collective formed in 1963 to nurture, mentor, and promote Black photographers who were excluded from both commercial and fine art photography. Here, the collective’s work is thoughtfully represented, particularly in a robust presentation of work by its original director Roy DeCarava.

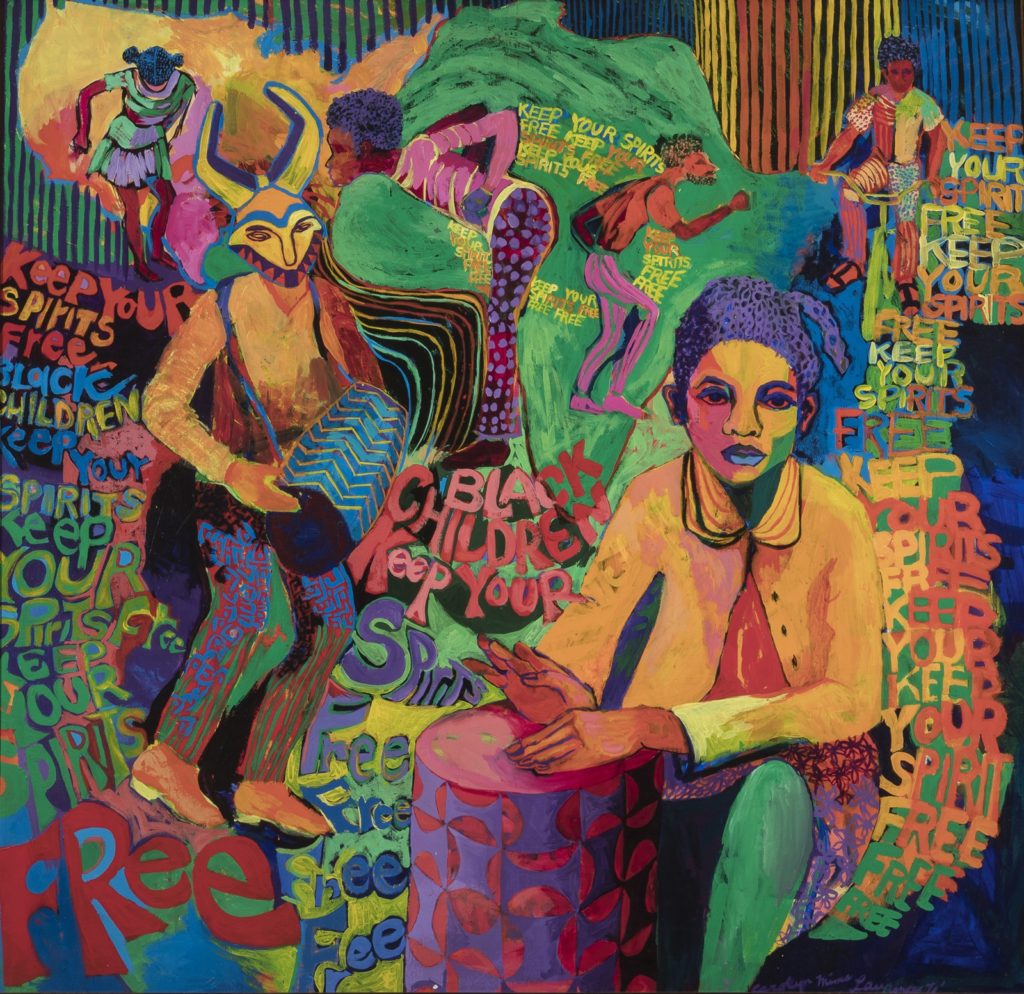

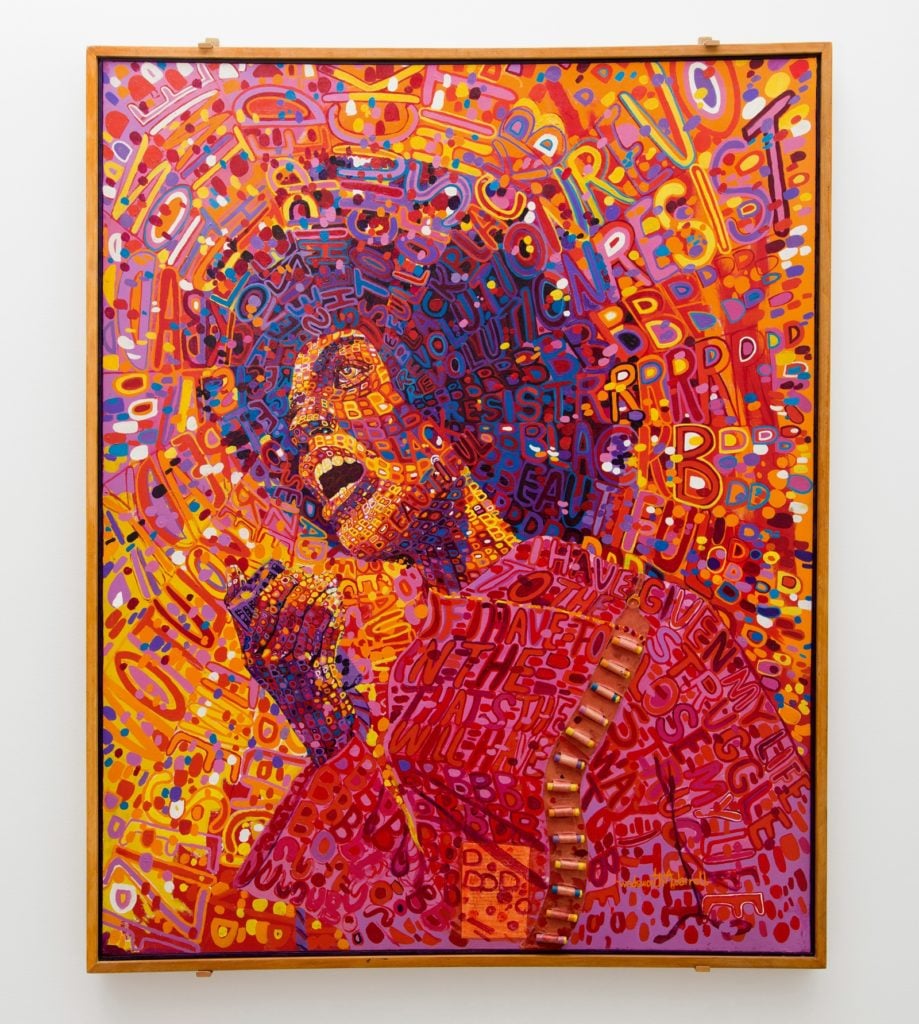

Wadsworth Jarrell, Revolutionary (Angela Davis) (1971). Photo courtesy Pablo Enriquez, courtesy the Broad.

Elsewhere, bold printmaking, painting, and fashion are the colorful standouts in a gallery space dedicated to Chicago’s AfriCOBRA artists.

But the Broad’s iteration of “Soul of a Nation” offered curators a unique opportunity to put an L.A. spin on the show, making slight curatorial adjustments that distinguish it from its debut at the Tate Modern or its Crystal Bridges and Brooklyn Museum versions. One gallery space, for instance, is dedicated to Betye Saar’s first solo show at the California State University, Los Angeles’s Fine Arts Gallery in 1973.

Installation view of works by Betye Saar in “Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power 1963–1983” at the Broad, 2019. Photo courtesy Colony Little.

The Broad’s associate curator Sarah Loyer worked closely with Saar to recreate the original exhibition, right down to the wall color: the dark, smoky grey paint allows Saar’s leather-clad mixed-media assemblages of Native American tribal talismans, Hoodoo shrines, and Mojo bags to pop off the wall. This particular series of installations, made from bones, twigs, beads, and other ephemera, ushered in a new wave of Saar’s work that centered on memory and the mysteries contained in found objects.

Betye Saar, Eshu (The Trickster) ,1971. Photo courtesy Colony Little.

Saar explored these themes concurrently in two iconic works, shown here in another gallery, this one dedicated to California assemblage. These works reclaim and transform imagery found in derogatory black memorabilia. The Liberation of Aunt Jemima (1972) and I’ve Got Rhythm (1972) are overt proclamations of reclaimed power.

Betye Saar, I’ve Got Rhythm (1972). Photo courtesy Pablo Enriquez, courtesy the Broad.

Here, such pieces by Saar are placed among subtler yet equally resonant expressions of protest: In Some Bright Morning (1963), sculptor Melvin Edwards uses welded metal machine parts, chains, and spikes in an abstracted meditation on the brutal history of lynchings. While its title references the lynching of Eli Cooper in 1919, it’s also linked to incidents of racial violence between the 1950s and early 1960s reported in Black journals like the Liberator and Freedomways.

Melvin Edwards, Some Bright Morning (1963). Photo by Colony Little.

The small-scale sculpture is one of three “Lynch Fragments” by Edwards that explore various themes of brutality, resistance, rebirth, and renewal. These powerful assemblage installations—along with others by Daniel LaRue Johnson, John Outterbridge, and Noah Purifoy—use found objects that tell one story and build new narratives, and the Broad show’s installation lets you see how they play off one another.

Prior to the 1960s, Los Angeles had a long history of both individual and popular efforts that focused on institutions that were slow to make progress on diversity and inclusion among artists in their collections, their exhibitions, and their community. The fruits of these long-term efforts began to manifest in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s.

Installation view of work by David Hammons in the “Three Graphic Artists” section of “Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power 1963–1983.” Photo courtesy Colony Little

At the Broad, curators Zoe Whitley and Mark Godfrey have recreated elements of a 1971 LACMA exhibition titled “Three Graphic Artists.” That show was born out of a grassroots campaign led by two LACMA preparators who had dedicated themselves to improving representation and access for African Americans at the museum. As a result of their advocacy, the Black Arts Council (BAC) was formed in 1968.

The combination of the networked activism of the BAC and Charles White’s art world gravitas rallied the support of collectors, entertainers, writers, and scholars to promote Black artists at LACMA. The show the museum organized in response, “Three Graphic Artists,” paired work by Charles White with two “emerging” artists of the time: David Hammons and Timothy Washington.

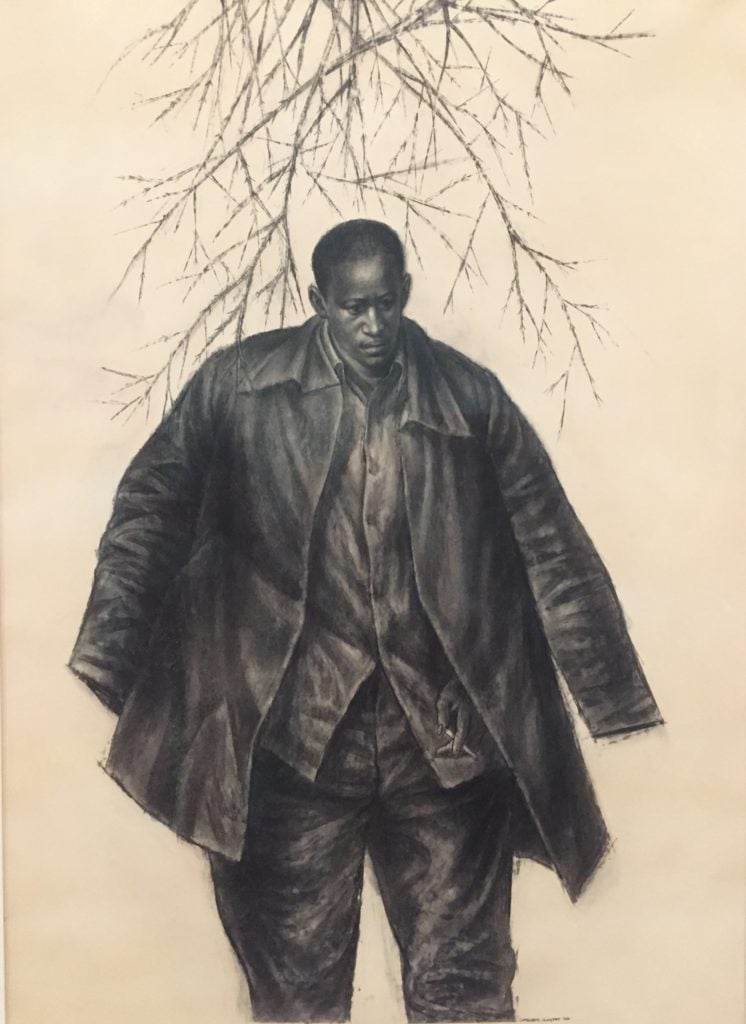

Charles White, J’Accuse! No. 5 (1966). Photo by Colony Little, courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York.

However, behind the scenes, “Three Graphic Artists” also proved that despite a shared mission, very real divisions and discord lingered: The 1971 show opened amid protests by members of the BAC who wanted to see Charles White featured in a solo, named show. As frustration grew over LACMA’s slow progress in hiring and promoting Black staff into curatorial positions—essential linchpins for promoting diversity within exhibitions and its collection—leading members of the Black Arts Council eventually shifted their focus away from LACMA, opting to create and promote institutions dedicated to African American art.

This shift in energy laid the groundwork for the creation of the California African American Museum in 1977. CAAM is the largest institutional lender in the Broad’s iteration of “Soul of a Nation,” making this show’s arrival in California a kind of return home.

David Hammons, Injustice Case (1971). Photo by Colony Little.

The section of “Soul of a Nation” dedicated to recreating “Three Graphic Artists” features a series of David Hammons’s seminal body prints, including The Door (Admissions Office) (1969) and Spade (Power for the Spade) (1969), shown with Charles White’s J’Accuse (1966). The presence of these particular works become timely reminders of present-day headlines about privilege in higher education and inequality in justice that continue to dominate the news cycle. The work offers fresh indictments on our slow evolution toward progress and reform.

Recreation of “Three Graphic Artists” in “Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power 1963-1983” at the Broad, 2019. Photo by Pablo Enriquez, courtesy the Broad.

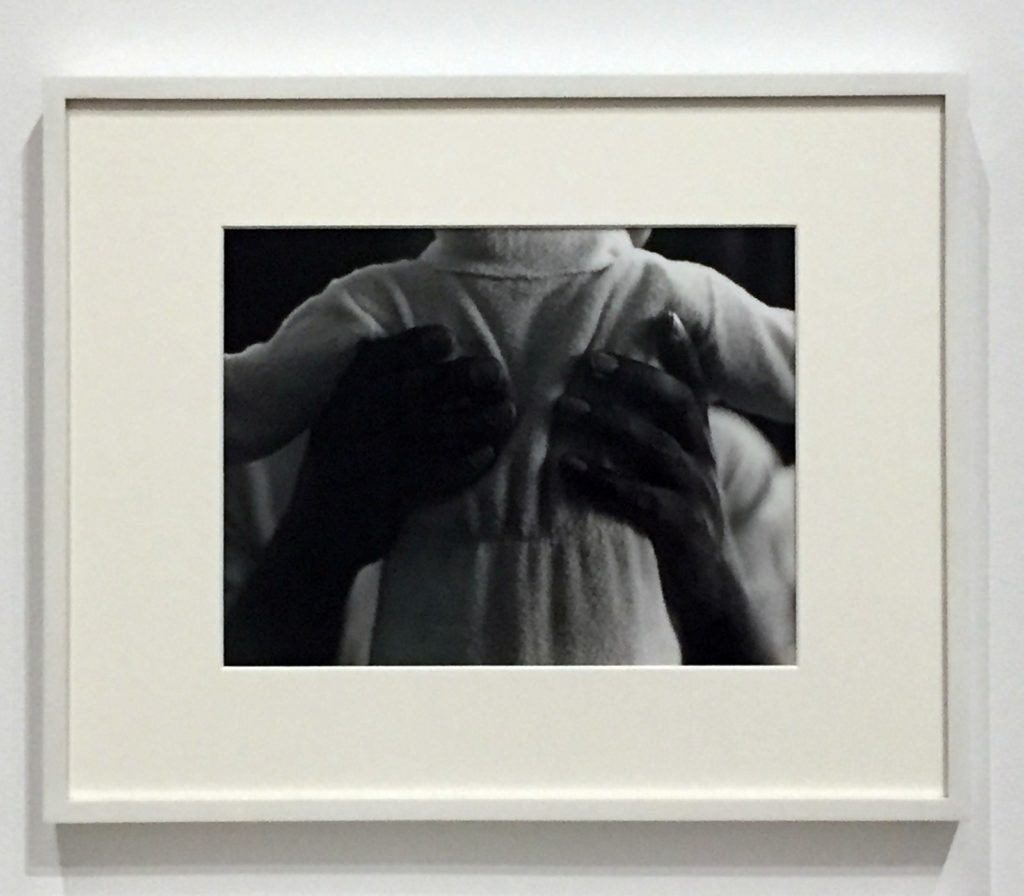

Overall, “Soul of a Nation” provides its viewers with an important, critical look at the art created during tumultuous times and its role in American history. In her book South of Pico, Dr. Kellie Jones cites a 1977 New York Times interview of curator David C. Driskell where he laments our compulsion to define “Black art” as a style instead of as a social construct that bears further examination: “I think it’s a sociological concept. I don’t think it’s anything stylistic. We don’t go around saying white art, but I think it’s very important for us to keep saying black art until it becomes recognized as American art.”

At the Broad, the dynamic stylistic range of artistic responses to the question of what “Black art” means only underscores the importance and relevance of this show—not just for understanding the past but for understanding this present moment too. It gives today’s audiences a strong argument for inclusion and for the urgency of continued, sustainable progress toward equity.

“Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power 1963–1983” is on view at the Broad Museum, Los Angeles, March 23–September 1, 2019.