No matter how you feel about Damien Hirst’s work, his place in history is secure, and his era-capping single-artist auction “Beautiful Inside My Head Forever” deserves a healthy share of the credit (or blame) for that. After penetrating the zeitgeist with fellow Young British Artists in the 1990s and soaring to superstardom on the rosters of White Cube and Gagosian, Hirst circumvented both galleries in 2008 in favor of consigning 223 new works directly to Sotheby’s London. To an unprecedented degree, how the original buyers would fare if and when they chose to resell the works later was simultaneously a great unknown and a moot point to the artist himself, who would collect nearly all of the auction upside.

Now, just a few days away from its tenth anniversary, the sale has come to symbolize both an inflection point in the world economy and a source of dramatic irony for anyone looking back. The storied investment bank Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy only hours before the scheduled opening of Hirst’s sale on September 15, 2008—a date now portrayed as the opening shot in the long-building financial massacre known as the Great Recession.

Yet “Beautiful Inside My Head Forever” could hardly have turned out better for Hirst. The evening sale boasted a sell-through rate of 97 percent, and the two-day auction as a whole generated just shy of $201 million in sales, trouncing its high estimate by $24 million. (All prices include buyer’s premiums, unless otherwise noted.)

Given the undeniable historical gravity of “Beautiful Inside My Head Forever,” it seems reasonable for art market outsiders to expect works from that auction to attract outsized demand when they become available again. Yet it has also been popular to point out the perceived retreat in Hirst’s auction market by highlighting the poor performance of one or two high-priced lots from his solo auction in later sales. Case in point: The “spin” work Beautiful Mider Intense Cathartic Painting (with Extra Inner Beauty) (2008), which originally sold for $1.2 million in September 2008, plummeted to just under $546,000 at Phillips London in March 2017. (This and all following figures are from the artnet Price Database.)

But is this a case of perception short-circuiting reality? Hirst has attracted between $18.5 million and about $32 million in total auction volume every year from 2009 through 2017. He is also already within that range for 2018, amassing $18.6 million in sales in the first six months alone.

Which begs the question: Has the legacy of “Beautiful Inside My Head Forever” been unfairly stained by a few cherry-picked failures? What would we learn from a fuller review of works from the historic auction that have come under the hammer a second time?

Damien Hirst in 2012. Photo: Carl Court/AFP/Getty Images.

Repeated Blows to the ‘Head’

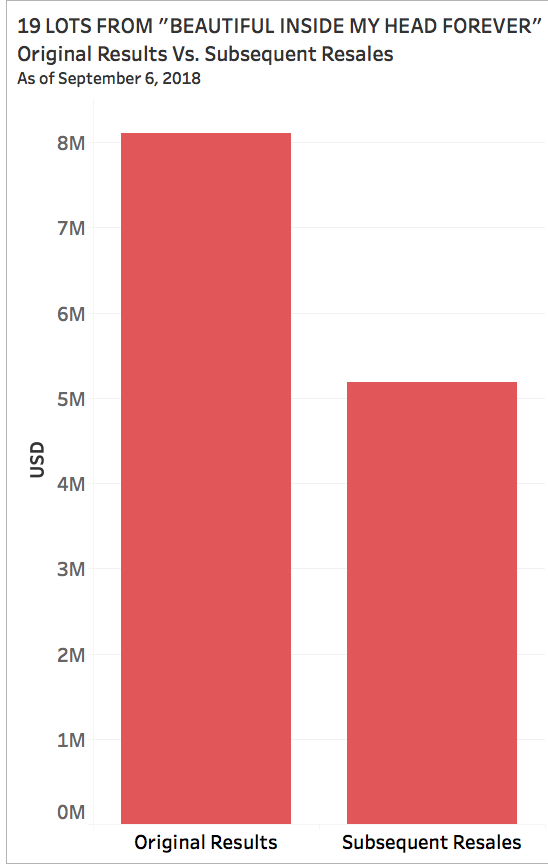

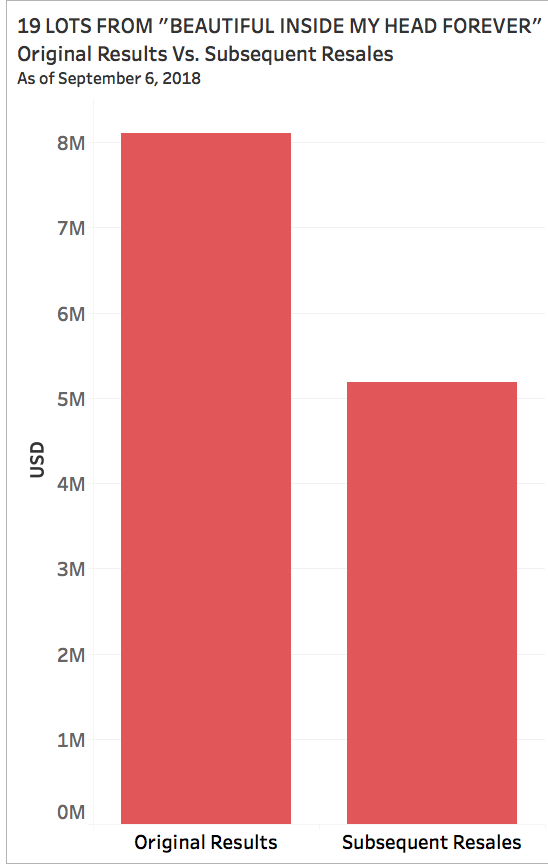

Using the artnet Price Database, I tracked down 19 lots from “Beautiful Inside My Head Forever” that have returned to auction in the time since. The chart below compares their total sales value in their debut with the total sales value they generated in their first respective resale.

Instead of a formaldehyde tank, the best fluid measure here is a bloodbath. After enticing buyers to spend $8.1 million at “Beautiful Inside My Head Forever,” the same 19 works only managed to bring in about $5.2 million after they each mounted the auction block a second time—a collective loss of nearly $3 million.

Is this grim total just a matter of a few horrendous results pulling down the rest of the group by association? Individual results thunder back a loud “no.”

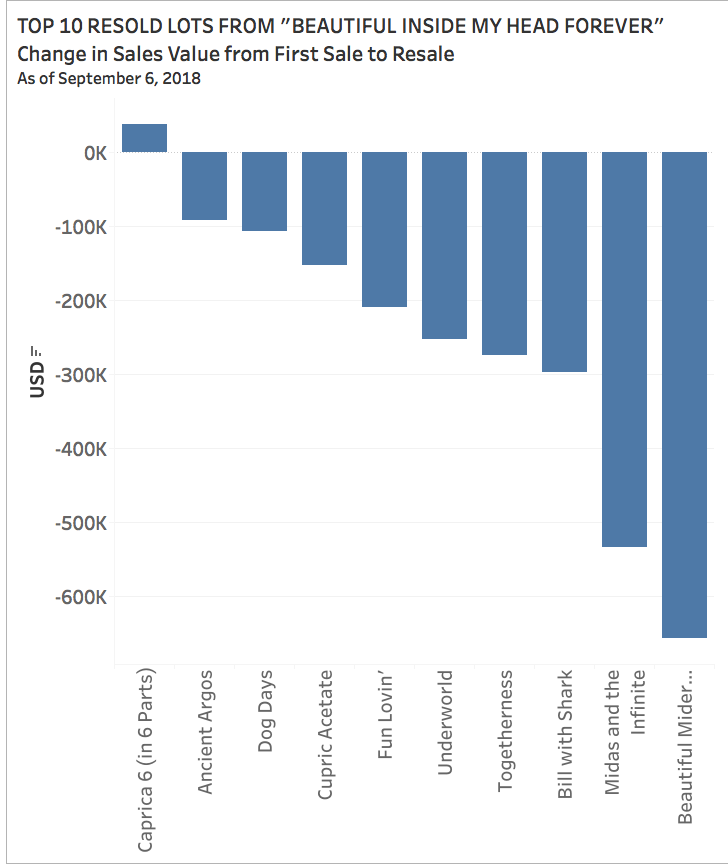

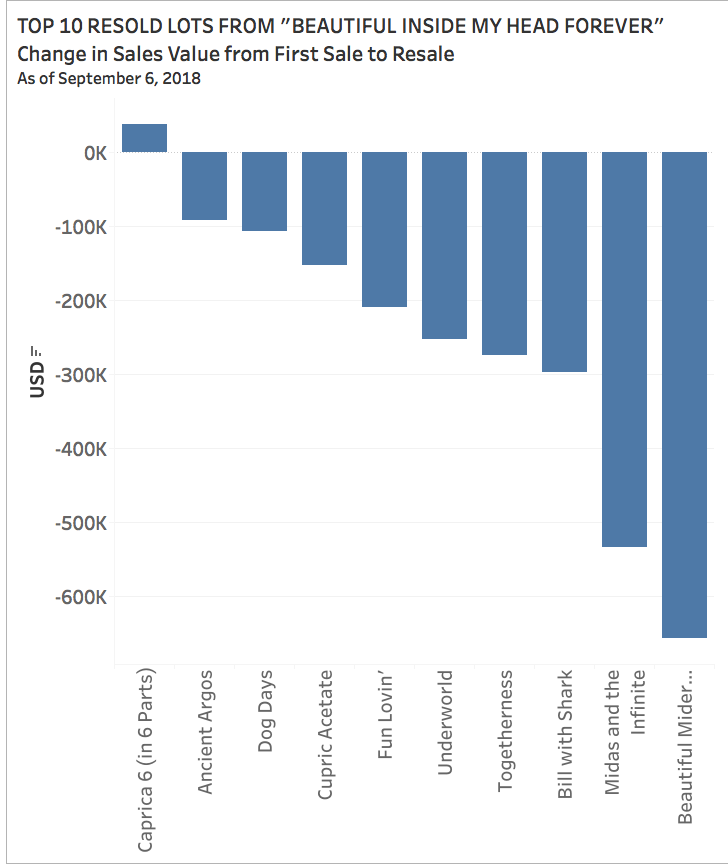

Below is a chart showing each of the top 10 “Beautiful” lots by sales value that have returned to auction—and the change in price when the hammer fell on them the second time.

In summary, only one of the top 10 works sold for a higher price when bidders got their next chance at it, and the gain in that case was an anemic $38,500—about seven percent above the original sales price. The others lost between $92,000 and $656,000 each.

All told, 17 of the 19 works resold at auction since “Beautiful Inside My Head Forever” shed value compared to their debut, and almost all of the declines were steep. Eleven lots posted a loss of more than 40 percent of their original sales price.

Larry Gagosian and Damien Hirst in 2007. ©Patrick McMullan.

Primary vs. Secondary

While the results for these particular works are grisly, we should be careful about which conclusions we draw from them about Hirst’s career. Felix Salmon, for example, has argued that the artist’s primary market has effectively rendered his auction market irrelevant, at least when it comes to the business of being Damien Hirst. Jay Jopling of White Cube has said that Hirst sold $110 million of new work in 2012, and the artist himself claimed that primary sales from his 2017 private museum blockbuster in Venice, “Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable,” totaled $330 million roughly a month before its end date.

Results have been robust in primetime galleries as well. Hirst’s Veil series—a new body of work inspired by Pierre Bonnard and uncharacteristically painted by Hirst himself—reportedly sold out in January at the Beverly Hills outpost of Gagosian, with whom Hirst reunited in 2016 after a four-year hiatus. Prices ranged from $500,000 to $1.7 million per canvas, with the grand total climbing to $18 million.

Still, the question looming over Hirst’s career today is the same one that “Beautiful Inside My Head Forever” first surfaced: Is demand for his work growing? Or has his market largely shrunk to a group of pre-existing stakeholders continuing to protect their investment?

It would be presumptuous to say that we have a definitive answer to that question based on how these 19 works first offered in “Beautiful Inside My Head Forever” have fared in the time since. Maybe, as Salmon proposed, “the buyers in 2008 bought because liked the work and wanted to own it,” not put it back on the block at the first opportunity. Maybe the works were bought by the usual mix of true believers and canny resellers, with most members of both groups anticipating the acquisitions will reach maximum value further into the future. Or maybe bidders who passed initially have decided that the pieces Hirst created for Sotheby’s simply aren’t all that desirable, compelling their original buyers to keep the works based on an unfortunate reality rather than a strategic game plan or an aesthetic attachment.

A much larger, more comprehensive analysis would be necessary to determine which of these options rings truest. For now, what I can say with confidence is this: If you bought works from “Beautiful Inside My Head Forever,” I hope it was for love, not money. Because their performance in the auction market since 2008 suggests there is relatively little of the latter out there waiting to pounce on a second chance at this bit of history.

Notes on Methodology

The 19 lots discussed in this post were identified by searching the artnet Price Database using an exact title match. This means that even a minor irregularity in the artwork data submitted by a later auction house, such as an added hyphen or parenthesis in the work’s title, would eliminate a piece from our search results. For this reason, the 19 lots should not be considered comprehensive.

For simplicity’s sake, the analysis also only takes into account each work’s first two sales at auction, meaning its original offer in “Beautiful Inside My Head Forever” and its first resale at auction afterward. Third sales and above are not included.